From Lawn to Livestock: Transforming Your Landscape into a Thriving Pasture Ecosystem

The Re-grazening

If you’re reading this, 30 pages in part 1 was just enough to get the taste buds responding to all of that photosynthetic goodness. I’m fairly certain this kind of unhinged rambling is best left at the back of a bar on a Tuesday night, but instead it’s 2023 baby and we’re putting everything on the internet for C O N T E N T. Welcome back.

In part 1, we covered the role of grasses and nitrogen fixers in building resilient pasture fields. We covered a bit about the role of both C3 — cool season— and C4 — warm season— grasses, and how a basic understanding of how these grasses grow can help us optimize our pastures to maximize production. We further talked about grass management and we dipped our toes into understanding the biological functions of grass in order to reduce the risk of overgrazing. With all that out of the way, we’re going to take some time to talk about some of the other aspects of pasture systems, and we’ll get into analyzing potential productivity through biomass calculation in order to figure out what kind of stock rates we can manage based on the efficiency of the pasture converting sunlight into stored energy for our grazers.

At the end of the last article, we had talked a bit about keeping nutrients and water on our site in order to keep energy for our system within our property. This brings us to the topic of erosion control, a major issue on failing pasture. Erosion control begins with proper pasture design. When designing pastures, you need to think about the expected movement of animals across fields. Problems with animal movement causing erosion occur more typically with a continuous grazing system or in a sacrifice lot. A sacrifice lot is exactly what it sounds like— a lot that is not meant to be utilized like the rest of the field— this can be for various storage, a place to keep your animals during heavy rains so the paddocks don’t get trampled too heavily in the mud, a place to keep animals while there’s a fence break, or a place to put animals if you are afraid of overgrazing your other paddocks. Generally, although not always, these areas are transitory spaces, and are often used to access other paddocks. Our goal is to minimize the amount of continuous use of land because just like us, land needs to rest in order to restore itself properly. There are a couple of key rules you want to keep in mind as you start thinking about the shapes of how you’d want your paddock system designed.

Now, you might be thinking, I don’t know anything other than a bit about grasses at this point, doesn’t it seem a little advanced to be jumping into paddocks? Well, not really. Paddocks can be as large or as small as you want, quite literally. If you’re familiar with chicken tractors— they are basically 8 foot wide by 8 foot long paddocks. If you’re not familiar with chicken tractors, they’re essentially a chicken run on wheels that can be moved to fresh grass once or twice a day. The function of chicken tractors is the same function of a paddock, on a massively small scale.

But, before I get to that, I realized there was something I forgot to bring up— if you’re interested in these practices, but don’t have the space, and want to get some experience, you may not be aware that in most suburban and rural areas, you can lease land for very, very cheap. While I hate Joel Salatin for a lot of reasons, he does have a lot of videos on youtube talking about how to lease land to run animals on the pasture. It’s obviously intimidating, especially if this is your first realization that this is an option, but it’s worth checking into, even if you’re only interested in running a couple chicken tractors for some meat birds to understand the mechanics of the process. Often times, folks won’t know what you’re talking about unless you’re in deep farm country, but you can often rent some easy grazing land for less than $10 an acre and with a couple of the meat birds your first batch of birds should pay off all of your equipment. So, yeah, even if you live someplace pretty suburban, if you don’t mind putting some sweat equity into trying to put some of these ideas into practice, you can apply some of these ideas without having to make a big investment.

Functional Planning

So, what can we do before even beginning to lay out our design in order to minimize the risks of erosion? The first is to design fields so that animals travel across hills, not up and down hills. When animals travel frequently up and down a hill, such as to and from their water source or to the barn, that path will likely become the path of least resistance for fast-flowing water, which can create dangerous ditches down the hillside. Take a look at the paths where you might hike and note how the exposure of roots changes quickly with the pitch of the ground and you’ll quickly see how much of an impact footsteps have on erosion. Pathways that travel along the side of the hill will slow water movement and help prevent ditches from forming in hillsides.

Alleys (lanes) are paths that provide a controlled means to move animals from one section of a pasture to another or back and forth from the pasture to a barn. If frequently used, lanes might need to be reinforced with gravel to prevent erosion. Now, when setting up alleys, be sure to make them wide enough to accommodate both the equipment you’re looking to use, not just to maintain pasture but to work on or move your fencing, but if you need to deal with injured animals. Your gates should be wide enough to allow machinery to pass through easily. If you’re planning on keeping your livestock within the confines of the paddock throughout the night, instead of sending them back to a coop or shelter, then you’ll want to place gates in corners where it’s easier to move animals through to another paddock. You should also think about in which direction the animals are most likely to move through the system and place gates in the corner closest to the paddock into which they’re being moved. What I mean by this is that if you’ve got 4 paddocks, for example, putting all your gates where the 4 paddocks contact one another reinforces the daily habit that they are traveling through that space every day, and reduces confusion, while also helping to reduce the amount of alleyway you’re trampling repeatedly.

Like we stated earlier, sacrifice areas are areas where you keep animals during inclement (i.e., wet) weather to prevent erosion and keep livestock from damaging pastures. When selecting the sacrifice area, choose an area with good drainage to minimize mud. Do not set up a sacrifice area beside a stream, pond, ditch, or wellhead, which might cause nutrient loss and devastation to your water source. One option you might choose when it comes to your sacrifice area is to use gravel to stabilize the area. Compacting the gravel and topping with a stone dust will not only keep animals out of the mud, but will also be friendlier for their hooves. If you’re grazing poultry, this might not be the best option for you, and you might want to just accept some areas will be muddy.

While narrowing down your options, consider locating sacrifice areas where it is easy to feed hay during the winter months when no grass is available for grazing in pastures. These areas can be reseeded if necessary in the spring, once animals are turned into other pasture areas to graze. By giving spaces more function, we are better able to utilize our space, creating more efficiencies which ultimately drive more resilience.

Now, when we talk about “designing” our pasture system, we’re referring to the overall layout of the fencing, watering, and animal handling systems. What path does the perimeter fencing follow? Where is the water source located and how will we distribute water to the animals? How do we make the most efficient use of our space to create temporary paddocks and minimize fencing materials? Where will be the most effective location for an animal handling system, and how will you configure it?

Answering these questions and others is part of proper pasture system design and is critical to the success of your system. You should have a system that is effective in allowing proper management of the pasture and livestock. The system design needs to allow efficient use of time and capital resources on the farm. These things are interconnected, and each property comes with its unique benefits and challenges, from soil types, trees and pasture already on the property, water resources, topography, precipitation, among dozens of other things. While we can’t control all of them, we want to find the best way to develop long-term low-maintenance systems to optimize our time and to create systems that require minimum input from industrial resources.

A well-designed pasture system should allow you to easily move animals from one paddock to the next, move livestock without unnecessary stress and safety risks, the ability to vary paddock sizes depending on the season— that is, to adjust what you need based on recent increases or decreases in livestock populations, a part of the year with less forage, etc. It might seem obvious, but it’s entirely necessary to make sure your equipment can get into the paddock spaces as well.

Paddocks

There are several things to consider when designing paddocks. We’ve mentioned a few, but ultimately it’s entirely based on the space dynamics— the water access, the topography, the biomass production, and so on. Further, you’ll want to consider the space needed to run fencing, whether permanent or temporary, and if you’re looking to get into the traditional practice of growing a hedgerow, the space required to develop those systems, which may shrink your paddock sizes considerably if you’re developing a small system.

A good rule of thumb is to use temporary fencing for a few years to allow you to determine the best paddock size and layout before installing more permanent subdivision fencing. Keep in mind that staying with temporary fencing indefinitely allows more flexibility in paddock sizes and assures that you have the option to clear out fencing to make things like cutting grass much easier. Further, temporary fencing is good if you’re building pasture and you need to keep your animals out of parts of your property.

Simple math shows us that if you want to use the least amount of fencing possible in a pasture, you’ll need to make the paddocks as square as possible. However, because most properties are not square or flat, we can expect paddocks to take on various shapes and sizes. And honestly, that’s not a big deal. One of the things you’ll learn over the first few years is that you find a certain rhythm to the work you’re doing; you’ll find yourself repeatedly going to certain areas that you didn’t initially expect, and you’ll start to fundamentally understand the landscape differently— things like tiny topographical changes will cause you to take different paths to places that you’d never have expected. Finding ways to utilize these paths into how our fencing is designed will make life easier for yourself, even if it’s not necessarily what makes the most ‘sense’ based on an objective perspective.

Paddock size often varies across the farm. It typically takes several years of grazing experience to learn what size paddocks work best during certain times of the year, so be patient. There are a number of factors that will impact your decision making, such as the number of animals you’re running, the projected dry matter availability and consumption, the timing of season and pasture growth rates, topography of the land, soil fertility, and soil productivity potential. This is why those temporary fences are so good at first. Even an experienced farmer will make adjustments to paddock layouts, so you should expect to as well.

Further, if you’re working on improving the quality of the soil, which will improve the amount of biomass production, what you produce, say, this year, won’t be the same as the next year, so creating a permanent paddock systems while the pasture is being rebuilt doesn’t make sense, and may cause more problems than solve. Further, if we size our paddocks based on future biomass volume generation, then you’re risking overgrazing the fields and destroying all of your hard work.

When you begin sizing paddocks, start by considering how many animals you expect to graze in a group. A good rule of thumb is to plan to have an average amount of forage available to feed those animals for four or five days in that paddock. This is just a start— some people will do intensive grazing up to the point where animals are being moved multiple times a day. There are benefits to this, not at the extent some proponents sell, and we’ll cover this further in the next piece.

The amount of dry matter, total livestock weight, and number of days you want the livestock to be on the paddock will combine to determine how large or small the paddock needs to be. Dry matter availability can vary greatly, even in forages of the same height. Forage species and density can make a significant difference in actual available forage. I know this is common sense, but it’s one of those things that doesn’t seem obvious until you say it out loud, sometimes. The point is, there are a ton of factors that will impact your rotation, and very few of them are things you have immediate control of, and so you need to be willing to be flexible. That said, you need to start becoming aware of what those things are so you can better predict and therefore prepare for the rotations you’ll need, and if you’ll need to supplement feed because of quicker grazing across paddocks and ultimately possibly not allowing the paddock to rest.

Pasture growth rates vary mostly by season based on species content in the pasture. Like we said in the previous episode, those C3 grasses, the cool-season forage species grow rapidly in spring and early summer, but slow drastically in mid-summer, and resume somewhat more rapid growth in late summer and early fall. Those C4 grasses, that is the warm-season forages will go through their most rapid growth period during the summer, with much slower growth in spring and fall. Differences in these growth rates will also impact the amount of rest a paddock needs after grazing. We covered this a little bit in the previous chapter; you’ll want to time your paddocks and seed your paddocks with this in mind, so the paddocks that are grazed in the peak of summer are primarily those C4, warm-season forages so that they’re eaten you can maximize your biomass volume, and the same with your C-3 cool season forages, which you’ll want to be grazing in the spring and fall.

And, obviously, there’s not a clear cut between these seasons, so there will need to be gradients of these types of forage as the paddocks continue on. It’s very much an art as much as it is a science, and there’s no clearcut way to set up your systems. In the future, we’re going to talk about tree crops— your fruits and nuts, and how we can use some of the methodologies we covered in the fruit tree episodes, such as clustered fruit harvesting periods, as a way to supplement our grazing systems. And that, right there? That’s where stuff gets exciting and I get annoying to people who don’t care about this stuff. When we create these systems, it’s like creating machines that can operate without almost any input by us once they are operational. There’s the need for us to maintain the grazing system, but the fields can be largely self-sustaining. And, I know, if you’re listening to this and you are running something like an intensive grazing system, you’re probably thinking there is still a lot of work involved, like running fencing and spot seeding, and all of that is true, but compared to traditional grazing or even factory farming, human input is significantly limited. In these types of systems, we have the opportunity to play with nature in a way that we set the stage and she takes off. It’s very cool to integrate various systems and theories to try and create something that is unique to you and your property.

So while we have talked about the soil, the grass, and some basics of how grazing functions in terms of the interaction between the land and animals, let’s talk about the land itself, specifically in terms of topography. Topography can severely impact grazing management. Cattle tend to prefer grazing low-lying, flat land, but will graze steep land and hilltops if it is necessary for them to reach their needed consumption. Sheep tend to prefer hilltops for grazing, but will graze lower and flatter land if necessary. Goats don’t care at all, and will— I promise you, they will— defy the laws of physics when it comes to getting to food. Temporary fencing can be used to design paddocks to have livestock graze where they are needed, when they are needed, as you learn the layout of your property. If we recall from the forest succession episode, the bottom of hills generally have more fertile soil, so 100 square feet, for example, of grazing space, will not produce nearly as much biomass for animal fodder as 100 square feet at the bottom of that same hill.

There’s other layers to this, because more fertile soil will also likely draw in different species of grasses and forbs, and water runoff will further impact this species diversity, which will impact grazing strategies by your animals. We talked quite a bit in the last chapter about seeds and targeting your seed purchases based on your soil properties, but we also should consider these microclimates caused by the topography of your property. This is why I had recommended watching the weeds that fill in and the wild grasses that compete with your seedling, because these will often be great indicators of subtle differences in your soil properties, some of which may come from slopes, topsoil thickness, and so on that you may not be able to find out without these indicator species. Like I said before, this process is as much an art as it is a science. This process is even more important for smaller properties where production maximization depends on every square foot and it’s possible to know every foot of the site, versus someone working on hundreds of acres. By targeting the right species in the right spaces, the pasture will be stronger and more resilient because the species are planted in the right places for their specific needs.

Now, even despite these easy examples there are substantial differences in productivity among soils, based on physical properties that are totally out of your control. Over time, you’ll learn which soils are the most productive on your farm. Plan for larger paddocks where soils are less productive. Your goal should be to focus more on having consistent rotations more than consistent sized paddocks.

When extra forage is available, especially during the spring, harvest these fields as hay to prevent the plants from becoming mature, as this decreases their feed value. If you recall from our quick chat on grass life cycles, the younger forage is more palatable, higher in protein, and digests easier. Therefore, when pastures are growing rapidly, graze the fields that aren’t easy to hay yourself, especially if you’re expecting to do it with a scythe by hand. During the drier and slower growing months of the year, the animals can graze fields more easily harvested for hay. In the next chapter I’ll cover it a little more in detail, but your C-3 fields, for example, if you’re getting good rain and sun you might be able to regraze the same field with only a few weeks apart.

Let’s say you have 6 paddocks, just to make it simple. 2 paddocks are all C-3, cool season grasses, 2 are a 50/50 mix, and 2 are C-4, warm season grasses. You might do a rotation that is the cool season grass, second cool season grass, one of the mixed fields, and then back through the cool season grasses, and do that rotation twice before ever hitting the warm-season grass field because you simply don’t need to yet because of how good the cool-season grass is growing. If the warm season is also doing pretty well, or even the mixed field, it’s worth considering cutting it down and storing it for winter feed, or supplemental feed if there’s a drought.

Water

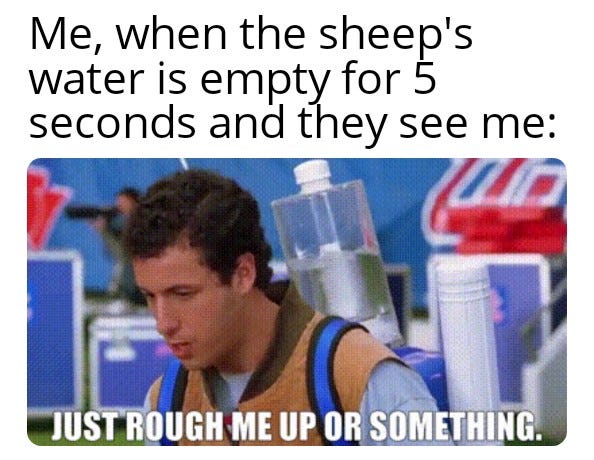

Much like us, our livestock’s primary concern is to have easy access to water. A good goal is to provide water within 800 feet of anywhere in a paddock. Research has shown that when animals need to travel further than this, they are less likely to graze further reaches of the paddock away from water. Over time this can lead to changes in the pasture in those areas and nutrient distribution issues across the whole paddock. An even better option, if possible, is to set up permanent water systems that don’t require inputs. This can be a challenge because we want to reduce runoff issues from our animals in the paddocks, but we also don’t want to rely on watering systems that require massive external input, whether that be from labor of pumping water and moving it around our property, or from setting up plumbing around the property which relies on other water systems. The goal is to create a system that reinforces its positive properties, right?

We can do this in a few ways. If we have access to streams, building our systems around those streams so paddocks all have access to that fresh water is an ideal option. It’s pretty unlikely, but if you do have long access to waterways in a way that all of your paddocks can touch it, this is your ideal situation. If this isn’t an option, creating man-made or animal-made water sources is a great alternative— this can be through piping water into each zone, watering cans located on each paddock that are filled as necessary, or small ponds on each site. We’ll talk about utilizing the landscape for water management in a later chapters.

Maintenance

Regardless of the animal species you own or are planning to own, when in the planning phases, it is best to consider where the logical place to establish a livestock handling system would be. For example, a thoughtfully designed handling system would be located where you’d conduct routine or emergency veterinary care for your animals (vaccinations, worming, birthing assistance).

The handling system does not need to be fancy or expensive, but it must be functional and established in the right location that is close by and accessible. I always think of the worst winter days and how far do I want to be trekking through the snow to deal with my animals. By thoughtfully planning your spacing, you’ll minimize your workload, increase the health of your animals, and protect the common areas like alleys and sacrifice areas, which both reduces your workload even more, reduces runoff, and makes everything in general easier to do.

While your primary goal, like I said, should be closer to your home (if we’re talking about homesteads or communesteads, which I’m guessing we are) rather than further, there are some other considerations, like locating it near the barns or other farm buildings. Remember to make it accessible for vehicles, especially trucks with trailers to load animals for transport. Consider access to electricity for lighting and electric tools, such as clippers. This doesn’t need to be simply grid power, but if you’re planning on putting solar panels on buildings or in a field.

Hopefully, despite my own reservations and worries about being totally underqualified to have these conversations, you’re finding some understanding that you, too, can do this if you choose to. We have to remember that many of these practices were done by our ancestors at some point in time. Every single one of of us, statistically speaking, has had an ancestor who was a farmer, and they likely came from hundreds of generations of farmers. In learning to treat the land as an equal to both us and the sentient life we partner with upon it, we are re-learning what is natural to us. The landscape around us, in fact, is only natural with humankind’s intervention— the fires ripping across California are a reminder that the land very much needs us as much as we need it. However, we have lost that, and it is only in us trying to find harmony in these practices, whether or not if we fail, will be be able to have a simple chance in resurrecting our relationship with nature and the survival of both ourselves and the planet.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to an 18 page chapter, of (so far) a 233 page book with 91 sources, you can support our work a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content (Episode 14), the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can subscribe on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.