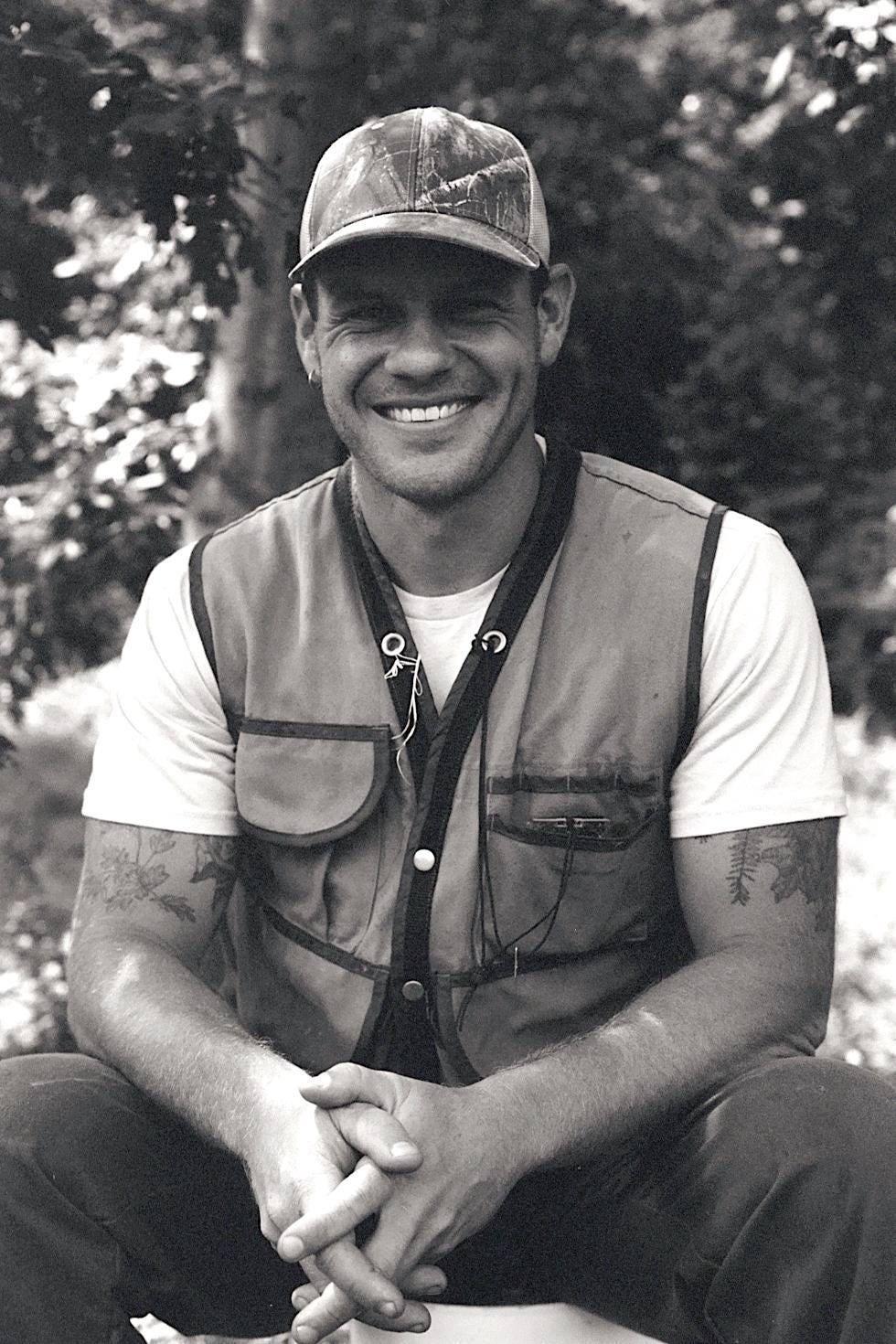

The following interview was recorded for the Poor Proles Almanac podcast with guest Ethan Tapper, a distinguished forester, author, and advocate for sustainable forest stewardship, based in Vermont. His dedication to forest conservation has earned him numerous accolades, including the 2024 National Tree Farm Inspector of the Year Award from the American Tree Farm System. This same year, he also transitioned to founding Bear Island Forestry, a consulting firm focused on responsible forest management. However, you might know him for another reason. He also published his debut book, How to Love a Forest: The Bittersweet Work of Tending a Changing World, which explores the complexities of forest care and our evolving relationship with nature, and that's what we're talking about today.

Andy:

Ethan, thanks so much for joining us. Can you tell us a little bit about your background and what drove you to decide I need to write this book?

Ethan Tapper:

Well, it's been a process. I've been working as a forester for about 12 years, mainly in Vermont, and there was just a lot of stuff I wanted to discuss. And I mean, the biggest thing that we encounter when we think about ecosystems for those of us who, like, really work in, you know, and care for these ecosystems is the the reality, right, that they're facing all these incredible, all these incredible threats and stressors.

These legacies of the past—non-native invasive plants, animals, and insects, pests and pathogens, fear, overpopulation, climate change, forest fragmentation, deforestation—you can run down the list. Actually, those threats and stressors collectively are referred to as global change. So they're dealing with this volume of threats and stressors.

These places are beautiful for those of us who may know a little bit about forests and like to walk. They're perfect and pristine, and once you dig into where they're at and where they are at this moment, you realize that they need help.

Yeah, you know, not in every single case, but in a lot of cases there are things that we can do to help them, you know, and then, by extension, our biodiversity and all of these things that we rely on forests to, like clean air, clean water, climate regulation, all that stuff.

Ultimately, we rely on these ecosystems. So what I wasn't seeing was a lot of folks with the idea that the only way that we can care for forests and their ecosystems is to leave them alone. Part of that's based on the fact that, like the last couple of hundred years in this continent, we have not done a good job managing these ecosystems in general, and we see a lot of exploitation of them. That does not mean we are incapable of caring for them. I wanted to write a book that I told that story about some of these incredibly nuanced and complex realities, these actions that we can take, these things that we can do to care for forests, and how those things, even something as counterintuitive as like cutting a tree, can be this like radical act of care for these ecosystems in this moment.

Andy:

Yeah, it's a beautiful book, and you do a good job of weaving some ecology education into these fascinating stories about your experiences as a forester.

You do this thing in the book where you italicize any like keyword, so like does have a little bit of that like academic, like educational, pedagogical component, without it being like distracting, which I think sometimes happens a lot with books like this, where it's kind of like beating it over the head. You don't do that, which I appreciated.

You bring up some really interesting thoughts, like philosophical points about how you felt, and like your reservations about the things you rationally believe based on the most recent science. But also, you're like, if I'm going against the grain, I better know what the hell I'm talking about, and that's frightening and daunting. And that humility in the process, I think, is essential in engaging as a reader, engaging with it, instead of feeling like, hey, everything you know about environmentalism is wrong, you stupid idiot, you're not doing that at all. You're like, Hey, here's what science says, and this is what I'm trying to do, and I could be wrong, but I'm going to try, and I'm nervous that I might be wrong, but we're going to see what happens, and that's nice.

Ethan Tapper:

Yeah, I say something in the book about the effect of if we wait to be perfect, we will do nothing at all, and it's like I think that in this moment we will do nothing at all. Yeah, you know, and it's like I believe that at this moment, we've got to have the humility to understand. We don't fully understand ecosystems, but you know they're incredibly complex. Still, we do know a lot about them, you know, and we can take action. We can do our best and then have the humility you know to recognize that there still may need to be adaptation on our part and resilience on our part and, you know, not everything's going to work out perfect, but that doesn't mean that we do nothing because we're too scared of making the wrong, the wrong move.

Much of the book is woven around my land, which I call Bear Island, which is like the most degraded site. When I got to it, it was the most degraded forest I'd ever been to. You know, one of the things I say as I was, I'm standing on this log landing. This incredibly degraded forest surrounds it is that I had to ask myself, right, if it would be a greater act of compassion to like leave this forest alone and hope for the best hope nature, you know, in air quotes, will take care of everything or if I was going to do everything in my power to try to make this place healthy again.

And one of my superpowers in this effort is that I am not a purist. I will not let the perfect be the enemy of the good, yeah, because I know that, even if our actions are imperfect, they're still going to be so much better than if we do nothing at all, you know, and just let these ecosystems continue to collapse and be degraded. You see, we have the potential to do a lot of good.

And then the other part of it is folks ask me, you know, I have this story on my land of 30 years ago. These loggers came and did what we call high grading in the forest, so they cut all the most valuable trees, leaving all the least valuable trees behind those most useful ones. The high-grade trees are also usually the healthiest in the forest. So they managed to make the forest less healthy. So what I compare it to, is, it would be like if you go out to your vegetable garden in the middle of summer— there's, you know, a bunch of vegetables, a bunch of weeds, and you weed out all the vegetables, like that, that's what this, that's what this felt like, really, and so, but the question that I get asked is like, you know, we look back at these actions that were taken historically on our landscape, and we're like. These people were so short-sighted, they didn't know what they were doing, and how do we know that 30 years from now, the next generation isn't going to be looking at us and saying the same thing?

Right, with all these things I'm trying to do to restore these ecosystems, there are many different reasons why. One is that I have the humility to acknowledge that these ecosystems are a thing in and of themselves and care about them as they are, not just what I can extract from them, which is a fundamentally different mindset than how they've been approached in the past.

But the other thing is that we will have the humility to recognize that we don't have all the answers. You know, we're not just going to impose this anthropocentric mindset on these ecosystems that's solely based on, like, seeing them as a commodity. Instead, we're going to, like, take a step back and recognize that we're not going to do the right thing all the time, and we're going to do our best, though, and we're going to keep learning and evolving and adapting, and that's what's going to make us different.

Andy:

Yeah, I agree with all of that, and you sum it up with, like, the discussion around invasive species, and that you go through the process of talking about using glyphosate. Was it glyphosate? So you admit, like I hope this is the right decision, but I'm going to own it, whether or not it's the right decision. I understand why people disagree with it. I also understand why people agree with it, which is why I'm doing it.

But, this greater, you know, this ownership of potentially failing, which I think is refreshing in a particular, especially in a social media era, where people like you and me get book deals because we have a social media, you know what I mean. Like that is a significant component of how books will be, you know, identified as sellable moving into the future, whether or not we like it, which means that we end up having to feel like we have to have this very refined existence and like any mistake means people unfollow you, which means that your future book won't sell or whatever it might be right.

So, admitting that you may be wrong and that this is what I'm going to do, and owning it is important because we have to address this generational issue of complex things. There's no easy answer, so I'm going to punt it and give a very mealy-mouthed excuse why I don't have to do anything.

And I guess an issue I have with some of the and this is going a little off track, but I think it does matter is like a lot of like the land back stuff, like I, I don't disagree with it, but I feel like it is kind of an excuse for some people just to say, like white people screwed it up, we should hand over the ownership to indigenous people, which I don't disagree with, but in the reality that that's not going to happen in any immediate future probably.

We still have a responsibility to try to undo the damage done. But that messy reality sometimes gets missed in that social media space that you openly engage with in the book, which, again, is important. Even if people disagree, it's all right. This is the first step to having an honest conversation about this instead of hot takes and gotcha moments.

Ethan Tapper:

Yeah, the hot takes thing is bizarre. I find that all the time where, yeah, it feels like a hot take is used as a surrogate for just not having a take, you know, and just not wanting to engage with the reality of something complicated, and because, again, it's the fear is like you start to inject some nuance into that conversation, like you start to say I used herbicide to control these non-native plants. You're shouted down before you even get a chance to do what I did, which is, you know, write about it for however many 20 pages or something.

There's a lot. We could talk about non-native invasive plants this entire time because there is a lot of interesting stuff about them, and that interesting stuff is what it does to people's brains when they think about them. Yeah, and you know, one of the things about the herbicide that's interesting is, you know, basically every conservation organization that manages these plants at scale uses herbicide, right, but, but the optics are so bad that no one talks about it, and then it creates this situation, where then it's like the perception is this is not happening.

And so then when people hear about it happening, they freak. You know, it's sort of like, even if something is hard, even if explaining something takes some nuance, if we're doing it, you know, if we believe in it, if we're like, this is what we've had this conversation about, which is worse, the invasives or the herbicide.

We've had this conversation about whether we can do this in a way that protects our soils, our waters, and our biodiversity, but like, behind closed doors, right? Because we're so scared to talk about this nuanced issue. And then the result is that we don't celebrate it, people don't know what's happening, and I'm like, if we're doing it, if we've made this decision, we should be talking about it and celebrating it. It goes for a lot of different things.

Andy:

And to that point, sorry, I'm going to cut you off just really quickly on this, because I think it pairs well with precisely what you're saying, is that what ends up happening is the only people talking about it are the people who don't like it. So when people talk about utilizing stuff like glyphosate, you have people like Tao Orian writing Against The War on Invasive Species, and they direct the narrative the same way, like when we watch politics, like whatever party is in power, the other party tries to direct the narrative about what's happening to the country. It's because when you're in control, you're accountable and can be criticized. When you're not in power, then you are the one who can blame everyone else because no one's paying attention to you. It's like, no, look at what these people are doing, that's bad.

And if you read Tao’s book, she makes it sound like they're just spraying the stuff from helicopters. We're like an actual war where we're just saying this 100 acres, we're just gonna spray it, no questions. You know who cares what's down there, and that's not what's happening, like it's not right, and that becomes a huge problem because that's the only person directing that narrative.

Ethan Tapper:

This is how I often describe it: invasive plants and the measures necessary to control them are an inconvenient truth. Right, and I use that in particular because sometimes you know when people are so uncomfortable with what would be necessary to control these planets. Right, including the suburban side at times, and instead of squaring up to that, you know, really thinking about it. They, you know, approach from a lens of, like, confirmation bias, right when they're, like, it makes me uncomfortable, just like climate change makes people uncomfortable.

And what information can I find that will affirm what I already feel? What expert can I find that will help me understand my feelings? And you can find someone who can corroborate just about anything you know. So then you take this framework of people not wanting to deal with the reality of the situation and then flocking to anyone who will tell them that it's not a problem. Or we'll let them know our ecosystems are going to adapt to these non-native invasive plants in any meaningful amount of time, or we'll tell them that they're climate resilient, so we should keep them, or they have medicinal value to humans, so we should keep them you know all of these, or photosynthesis, yeah yeah, or they're right ever, and it's just like you know.

I wish we could ask the question instead of doing that. And it's the same, you know, it's the same that I end up dealing with when I talk about the other things I talk about in the book, like cutting trees and killing deer, which is like, instead of just reacting to this, can we just like look at it for a second, you know, and can we just like, instead of initially being like, this is how I feel about it. Now, let me reverse engineer a reason why I feel this way. Let's accept the possibility that the fact that something makes us uncomfortable, like, doesn't mean that it's wrong. There might be information that shows us that, even though it makes us uncomfortable, it is something we need to do, and that's what the whole book is about.

Andy:

Yeah, I mean when you were talking about hunting the deer for the first time, at least since you were a time like a child or something like that, you know that process which, as somebody who has butchered livestock like I'm, very familiar with that first initial kill and the realization of, like I'm, I am 100 percent responsible for this animal's death. It's not like going to the grocery store, where it's like this animal was killed, whether or not I was going to eat it. Now the question is, will it get thrown away if I don't eat it? And do I have a moral responsibility to eat it, like it sacrificed its life?

Instead, you're completely cutting out that middleman and having to own that moment and even as somebody who can rationalize which I think most people can rationalize, at least the people that eat meat why it's necessary to do that, owning it 100% and owning the risks of suffering and all the other components that come with it, is a very heavy burden.

That I think is essential for everyone, especially people that eat meat, at least to experience once, whether or not it's deer or some other animal, to understand the gravity of their decisions, even if it's a, you know, a one-time thing, to to claim some ownership of that, I think is essential and you kind of go through that a bit.

So, up in Vermont, though, to speak to the deer, like I know, and if, when I talk to different people in different parts of the country, populations are like from 50 per square mile to 200 per square mile, depending on where people live, and, for context, I believe most ecologists suggest that, like, less than five is the ideal amount of deer somewhere around there and it depends on the ecosystem yeah, all those other components, how bad is it in Vermont right now, if you happen to know?

Ethan Tapper:

It's not that bad compared to most of the country. I mean, I think we we have less than 40 per square mile, and in some parts of the state, like we have this northeastern part of the state that's pretty boreal and you know, in there it's like way lower, but in other parts of the state we think that we can sustain like 18 to 20 per square mile in these degraded ecosystems. That's where they want to lower it to five to eight to let that ecosystem recover, and then maybe in some, you know, future world, they could sustain more, like 15, 18. But yeah, it's not that bad, but it's also more than our landscape can sustain.

It's still too many, you know, and they eat an enormous amount, especially in the wintertime, of these young trees, shrubs, and plants as well. They can change the composition of a forest, you know, and by eating some species of trees and not eating others, they might change the composition of that forest for centuries, which is wild to think about. And the situation is basically as it is across the country, like a few different things drive those overpopulations. Right, they're driven by predator extirpation.

Here it was like wolves and the Eastern cougar, what we call in Vermont the catamount, and then also other things like decreasing winter severity, which used to be a significant driver of, you know, keeping that population in check, and then and then a bunch of other stuff related to the, the inability of its current predator, which is apex predator, which is humans, to regulate that population. So that's things like suburbanization, posted land where people can't hunt, stuff like that, and, you know, really crashing hunter numbers. Humans are the apex predator of this animal now, and those other things diminish our ability to limit those populations and to keep them low.

But something interesting in most of the whitetail deer's range is that, according to the research, once you get above 40 deer per square mile, their recreational hunting alone is no longer an effective means to control that population. So what that means is you've got to do something more drastic. You've got to do culls right, like you've got to call in snipers and kill a bunch of deer. And then there's, of course, a lot of social resistance to that.

There's social resistance to the impacts of deer overpopulation, such as deer-car collisions and tick-borne disease. People can't grow food in their gardens, and farmers can't grow food in their fields, right? There's also resistance to the measures necessary to control them. So people try to treat it symptomatically, and they treat it with deer exclosures, and they try to sterilize them. Ultimately, all of that is just to get ourselves off the hook of having to deal with the fact that we got to call in these snipers and, you know, kill hundreds of deer.

Ultimately, that is such a greater act of kindness to everything and to the deer themselves.

Andy:

You don't think it's good for them to starve to death?

Ethan Tapper:

Yeah, exactly, I mean one of the things, like people say, when deer get overpopulated, they get smaller, they get in poor condition, and what that is is that there's so many of them that they've stripped all the most nutritious food off the landscape, you know, in addition to anything like spreading disease and stuff like that. But that's why they get smaller. They've eaten all the most nutritious food, and I'd rather have a smaller population of deer that was healthier and not suffering, than a large population of deer that is completely unhealthy, you know, and entirely out of whack.

Andy:

In addition to their, you know, the fact that they're essentially thriving in an ecosystem collapse, and you know, diminishing forest ability to be resilient and healthy, and reducing their ability to provide habitat for literally tens of thousands of species of other organisms. So I think it's really interesting though, that you've brought up is that like people don't want to cull these deer, despite like these obvious and objectively like good reasons that like we don't want them to suffer, we also want to have all these things that the deer are making not possible right.

With social media like this mealymouth, I don't want any of these. Still, I refuse to own the fact that one of these things has to happen, like somebody else needs to make this decision, and if it's the wrong one, or even no matter what it is, I'm going to criticize it because I'm not happy with either of them. Given the recent election, that feels poignant. I don't like either of these answers and don't want to have to put my name on either of them, but I'm going to criticize anyone who does, because there's no real alternative. It is so symptomatic of the world we've developed that we cannot tackle difficult questions.

Ethan Tapper:

It makes me think of a few different things. One thing it makes me think of, and I wish I could remember who said this, but someone was talking about how maybe a freedom that we've lost is the freedom not to have a take on something. There's a lot of stuff we don't know much about, and we don't know enough about it to comment on it, but if we don't say something about it, we will also be criticized for that. When really what we should do is listen and try to engage with the nuance of it, rather than just feeling like you know, I have to post something on my Instagram story about this thing, or people are going to be like, Why didn't you have a take on this thing?

Andy:

And why wasn't it the right one?

Ethan Tapper:

Then, I thought about something I heard on this podcast, Hidden Brain. On Hidden Brain, recently, they had a scientist come on who's talking about ambivalence, you know, and the wisdom of ambivalence in a way that we think about it as something that's like a weakness. Yeah, that we have to feel like just one thing about something. We have to know precisely how we think about it and really like there's a lot of wisdom in acknowledging that we can feel a lot of different things about something and that that's, you know, actually so much more of a real expression, a real reaction to the complexities of where we're. But that is also something that's hard to express in the kind of little bites we're trying to do.

Andy:

Yeah, it's a strange time to be alive. I'll say that.

This also points to what you talk about in the book, and I will quote you for a second. So you said in the book, “We cannot choose if we want to impact ecosystems, but rather what we want that impact to be.” And I think that really points to the whole thing with deer, invasive species, endemic species, protecting them, and how we do it, and you didn't go into this in the book. So I'm curious about your thoughts about ecosystem restoration, given climate change and climate refugees. We have a footprint, whether or not we want to own it. How do we wrestle with that? What does that mean in a world of ecological climate refugees? I'll clarify I'm speaking about plants, not like people.

Ethan Tapper:

Well, so you know, to that the point in that in that quote in general, right, like it's, it's another sort of thing, some like that dichotomy I talked at the beginning, that we can just be like hands off these ecosystems you know you're over here and we're over here and that's how we're going to care for you. We need to acknowledge that, like they are, they're not separate, right? Ecosystems sustain us, and everything we do impacts them.

Everything we eat, consume, and wear, you know, every bit of energy that we can consume impacts ecosystems, and we need to know that rather than pretend that's not happening. And we also got to make compromises. Everybody loves a beautiful tiny home and an agricultural field, and all those things are the site of a drained wetland or a clear-cut forest. And you know, those are things that we recognize as necessary compromises to sustain our lives and to hopefully sustain beautiful lives and, you know, worth living and, you know, full of all the good, all the best things in the world, but we need to acknowledge that.

And one place that I think about that in the forestry world is, like, with wood, you know, and because that's another thing where, like, managing these ecosystems, a lot of times I manage ecosystems. I'm doing ecosystem restoration, I'm producing wood in the process, a local renewable resource, which we say we want more of. Still, it's also a resource that can be harvested while you're helping these ecosystems heal and while you're helping them become more like old-growth forests and providing these habitats that are underrepresented across our landscape and which are foundational habitat for all of our biodiversity, and in that case, it's like the best thing imaginable, right?

But it's a compromise, it always will be, and we should be trying to look for ways to have a positive impact while also getting the stuff we need. For me, forest management can be its not always, certainly, but can be an example of that, rather than looking for ways not to impact ecosystems, which isn't even possible anyway. You know, I'd rather be recognizing that impact, owning it, and then trying to do stuff that does that in the best way possible.

I have one more quote that is special to me from the book, that makes me think of that, which is from the last chapter, and I just I haven't memorized, because whenever I do a reading for the book, I always read this reading at the end and, it says this world is not ours to hold. That we have it anyway. Yeah, you know. And so it's one of these things where it's like, yeah, we're in this biosphere and surrounded by these ecosystems and all this stuff that's beautiful, has its own life to live, and is of intrinsic value.

We can talk all day long about how we shouldn't be, we shouldn't have sovereignty over all these things, or we shouldn't be able to dominate all these things, and they shouldn't be subservient to us, or whatever language you want to use. But like, here we are, and we are the organism that you know, holds the fate of this world in its hands, you know. And so we can pretend and use these philosophies to get ourselves off the hook from that reality, or we can just be like, yeah, we depend on these ecosystems. In this moment, they might be dependent on us, and you know we talk about regenerative or sustainable energy, and that force can do that.

Andy:

But it also points to the fact that we have to acknowledge the straightforward reality that we consume too much, like it's very easy to point to the past and say I can't believe you cut down these great trees, but that was e but that was energy that they needed to use to build their homes, the homes that many of us live in today. I'm not saying that there wasn't any waste, because there was, but they were no more or less flawed than we are.

But we also now know more and have a responsibility to the world around us to be less flawed, that we don't have the luxury of an environment and ecosystem that can absorb our mistakes anymore, because of population and just energy consumption per person. You know, like you think about what it is? I don't know the date off the top of my head, but it's like we've consumed more energy in the last two decades than in the previous 500. Even like the last 30 years, that was known as a drop in the bucket compared to what we're consuming today.

So it's not as simple as “Oh, they were idiots back then, or you know, they were stupid, they didn't understand. We know better.” We can make these changes to our land management practices with a comprehensive understanding of our relationship with the world around us and ownership of the decision-making, instead of just punting it on. You know, abstract ideas or concepts about, oh well, I have no control over what BP does. Like, yeah, that's true. But also, like, how much crap do you buy that you don't need?

You can criticize one and also acknowledge your shortfalls.

Ethan Tapper:

I read this book called Saving Us by Catherine Hayhoe, and she talks about the fact that, it was in 89 that BP actually created the individual climate carbon footprint calculator.

That was a means to lay all this stuff at the the individual's feet and distract from their own oversized impact on the situation. You know, and individuals like, individual action has meaning and is impactful. And we should, and we do need to, make better choices individually. And then it's like that and big-picture stuff as well.

Andy:

Yeah, to your point about the ambivalence, it's the same thing, like this and that, and they might be diametrically opposite positions, but that doesn't mean they can't both be right in some capacity.

Ethan Tapper:

I talk about that in the book all the time. The forest is like the world, where seemingly contradictory things are true. You know where you can have forests that are both competitive and collaborative. You know altruistic and parasitic. You know that you celebrate life and celebrate death. You know, in ecological terms, all those things can be true at once, and like that's what's cool about it, that's what you know. It's like it breaks our brains and makes us experience all this dissonance, but that's the best part right there.

Andy:

Yeah, and it's a little bit of our brains trying. Maybe you can sympathize with this experience of like, if you're in the woods for a long enough time, you feel your brain being different and like you feel like the world outside of it almost seems irrational for like a split moment before your brain's like no, you live in a house, like you do all these things, but like, for like a split second, a part of you is like that seems wrong, even if, like you can rationalize that it's not.

And I like this idea of these two oppositional forces making sense in this unique environment we have co-evolved to exist within. I don't know, it's really interesting and something I've experienced. As somebody like you in the book you talk about, like you would go out into the woods with your dog and be out there the entire day, not talk to a person, yeah, I'm curious, like if you had that same kind of moment, like coming home, where it's almost like this is wrong.

Ethan Tapper:

When I had it, I talked a little bit about a book and how I got into this forestry in the first place, or being interested in forests and forest ecology, because when I grew up, I didn't care about it at all.

And what happened was that my high school girlfriend went off when I was in college, bumbling around. I didn't know what I wanted to study. She went off on this program, this like five-month wilderness expedition, and when she came back, she'd had this huge impactful experience, and I had not, and we were not connecting, and I was afraid we were going to break up. So, like snap judgment, I was like You know what, I'm going to do, I'm going on a wilderness expedition. The next one leaves in two weeks and is six months long. It is like three months skiing north, and you build a canoe and canoe back down.

It changes the way you think about everything.

You know it was the most wild thing was becoming so overwhelmed when we went like we're going back into kind of society the colors and the brightness and the sound couldn't handle.

I remember coming out and looking at a soda cooler. It hurt my eyes to look at the brightness of the colors on the labels, and going into a big grocery store, I had to run out because it gave me a splitting headache. Just the lights, yeah, it was wild. So that, yeah, that has happened to me in it, raises many interesting questions about what we're subjecting our brains to. And there's another reason why it's such an existentially vital thing to do to protect these ecosystems, right, because you know, we know they're important to us, like physically and culturally. Still, they also have all of these other special values, and we want to have a future where future generations can go out there and be in the woods and have that experience.

Andy:

In the book, you discuss putting the land into a land trust, which I think speaks to this protection of the land. I don't know if you could talk a little bit about what that process was like for people who might be interested in doing something like that.

Ethan Tapper:

Sure, I put a conservation easement on it and donated a conservation easement.

I still own the land. What I did was donate away the development rights to a local land trust. And you know, when I was younger, I remember someone asking me about that concept of conservation, and you know, permanent conservation with the conservation easement, and I was like, I don't know, forever is a long time. And then, just as I grew up a little bit, I started to see that this is the only way to ensure that this land is still going to be here. In 50 years or a hundred years, you know it's in perpetuity, whatever that means, but it's as long as we can imagine.

As long as the United States exists. And as long, yeah, as long as, like you know, these systems, as we know them, exist. But it's the only way we can be sure. And so it felt like me, like giving a gift to future generations.

But what it essentially is is you work with a land trust, usually, and they draft up a document called the conservation easement. That easement says what you can do and what you can't do on the land, so I can't subdivide the land, I can't develop it, I could build an agricultural structure, but I couldn't convert it to another use. There are different purposes of grants; for example, there might be grants that are easements rather than agricultural usage.

Mine is about biodiversity protection, so I can manage the forest, as long as I manage it with my primary intent: protecting biodiversity. You know, hunting's allowed. I made it so that public access is permitted forever, which was just like an equity thing for me because I recognized that, like not everybody, most people don't get the privilege to own big pieces of land. We got to make it so that people have places to go, even if you don't own, you know, a piece of land where you can be out in the woods, which was also a significant compromise.

It feels very personal, and the idea of people being all over it is scary. Still, also, you know, I think is is representative of a lot of these significant compromises that we need to make, you know, and and we're managing these ecosystems for a lot of different things we're managing them for biodiversity, we're managing them for water, we're managing them for air and climate mitigation. We're also managing them for biodiversity, we're managing them for water, we're managing them for air and climate mitigation, and we're also managing them for people. So, trying to strike that balance and make those compromises is essential.

The interesting thing about conservation, though, here in Vermont, at least, with agricultural conservation, what they'll do is they'll do an appraisal and they'll be like This is your land unconserved. This is your unconserved land; this is your conserved land. Then, the difference between those values is the value of your easement, and if it's agricultural land, they might give you a check for that amount of money and compensate you for that difference in value. With forest land, there's just no funding for that. So there was a time where I was like I don't know if I can afford to give away hundreds of thousands of dollars of value in my land because I'd have to pay a land trust $20,000 to do all of their legal expenses and to monitor that easement in perpetuity and to, if some future person violates the easement, to take them to court.

So, I ended up working with a local land trust. I was able to do it for nothing, but it was interesting. What is this world? I'm doing something that is for everybody, you know, and this is a great act of caring for the values that we all share. If you want to give away that value, you must pay this exorbitant amount of money. That felt out of alignment with me.

Andy:

Yeah, no good deed goes unpunished, right?

Ethan Tapper:

Yeah, it's definitely. It can be that way.

Andy:

Yeah, and I thank you for doing it. I think it's great that you did that, and I do think quite a few listeners have thought about the idea of the land trust, and it's an intimidating thing for all the reasons you've pointed out. Yeah, you know the cost, and you know there are attorneys involved, so it's never going to be cheap. The perpetuity component of it—there's just a lot to it.

Ethan Tapper:

Yeah, it's scary.

Andy:

Yeah, so I appreciate you talking about a little bit. So this book came out. What, last year? You said you are working on some new stuff, but it won't be out for a while. Where can people get your book?

Ethan Tapper:

Anywhere the books are sold. I always tell people that if they have a choice, they should support their local independent bookstore. You can get it anywhere, and you can get it as a hardcover, ebook, or audiobook. But I've had such a fun time, you know, on this book tour, doing just like hanging out in libraries and independent bookstores, which are, I've realized, incredibly radical spaces. You know, especially in this, those are not easy things to be right now, and they're both radical in different ways. So support your local independent bookstore. They're like the best places in the world.

Andy:

You're also on social media so that people can follow you on Instagram. I don't know if you're on Facebook. I'm assuming you're on TikTok or YouTube, but I don't use TikTok.

Ethan Tapper:

And it's all under @howtoLoveaForest.

Andy:

We made this whole episode somehow without actually saying the book name. So yes, it is called How to Love a Forest. It'll be in the show notes, Ethan. This has been great. I'm excited to see your next book come out. It was a fantastic read. I will recommend it to a few folks, and if you haven't read it before, please, if you're listening, go check it out.

To listen to this interview, tune into episode #257 of the Poor Proles Almanac.

Great conversation! Thank you. Crazy about the cost of the land trust, shows what our society "values".