Exploring Food Sovereignty and Cultural Identity: The Decolonization Diet Project with Dr. Martin Reinhardt

The following interview was recorded for the Poor Proles Almanac podcast with guest Dr Martin Reinhardt from the Center for Native American Studies at Northern Michigan University. The Decolonizing Diet Project is an exploratory study of the relationship between people and indigenous foods of the Great Lakes region. Very few studies have ever been conducted on this subject matter, and studies that examine the physical, cultural, and legal dimensions are practically non-existent. This research explored not just how to eat as people on the landscape ate in the past, but it looked to see how to integrate this past with the present and to see how a diet framed in native berries, leeks, wild game, whitefish, maple syrup, wild rice and much, much more changed the quality of living for its participants. This was an exciting and inspiring conversation, and it's one I think you guys will enjoy.

Andy:

Marty, thanks so much for joining us. Tell us a little bit about yourself and this decolonization diet project.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, glad to be here, Andy. I'll introduce myself traditionally first. I'll introduce myself traditionally first, zebing and dadding.

So it's important that we introduce ourselves in a traditional way. That way, we're acknowledging we're from here, and I think that when people are so fond of land acknowledgements today, I think sometimes they lack a sense of what it actually means, especially to the indigenous folks who are from the places, that other people may be starting to recognize the indigeneity. But you know, we've long recognized our identity goes very deep in these, in these lands, and so I think that's an important way to start.

And what I said is my name in Anishinaabemowin, our native language, and that's a hawk coming down out of the Eastern sky is my traditional name when it's translated into English, and I'm from the place that we call Bawateng or place of the rapids. You know, my family comes from both sides of the border. That border really means nothing to us between the United States and Canada, our Anishinaabe Three Fires, confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa and Bodewatomi. You know we've always known these as our traditional homelands, this Shike Minas, this Turtle Island, and so I think that is really important to remember.

My family is Crane Clan. It's one of the three leadership clans of the Anishinaabe, and so I take my clan responsibilities very seriously in making sure that I spend a lot of time thinking about these leadership issues and try to get them right, or as often as I can. We all make mistakes. And then, lastly, I just wanted people to know where I live. Where I live is not where I was from, and so I live in Kichina, mimine Zibi, a place that we now know as Marquette, Michigan, in a colonial capacity, but for us it's going to be more known deep historically as the place of the Great Suckerfish River, and a place that you know I've really gotten to know since around 2001.

My family certainly passed through and lived here a long time ago. But for me, it really began in 2001, when I came to work at Northern Michigan University.

Andy:

This will be a really great pairing with a recent episode we did that was focused on beyond land acknowledgements, which I think plays really intimately with this idea of food sovereignty and even like if you're thinking further out, more peripheral, this idea of like the locavore movement or like local food, or rethinking what sustainable food systems mean, like all these things are really closely tied together and I think trying to separate those things completely is not just doing a disservice to each of them separately, but also I think it's focused more on like making white people comfortable with the subject matter by talking about like local food without like okay, why is it local? Let's talk about what that really means.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, if you separate that from colonization, it certainly does diminish the original acts of oppression, right, the original sins. So, I think when you think about colonization and slavery, you can't separate them. If we're going to heal, then those things are certainly part of the healing process. But we have to have accountability first, you know, before the healing can begin.

Andy:

I came across your project I think I don't even remember how I did actually, to be completely honest and I just like got sucked into. I found one of your slideshows that you had done, and I was just reading through all the data that you guys pulled in. It was just really cool and really different than, I think, what we see with a lot of like NGOs that are focused on this idea of like foodways and food sovereignty, and that there was a real focus on meaningful experimentation. So could you talk a little bit about, like, what was the impetus for this and kind of what drove you to be like, “We're not just gonna talk about it, we're gonna like do it, and we're gonna do it outside of a laboratory,“ so to speak?

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, so you know it goes all the way back to my time working down in the Mount Pleasant area at Central Michigan University. When we worked there, we began a tradition called the Anishinaabe food taster, and so in November, as part of our Native American Month activities the student organization there and the Native American Center we would provide this meal for the community, and it would be very reflective of the foods that we saw as Native American foods, and so we brought that tradition to Northern Michigan University when we came here in 2001.

Eventually, it was renamed to First Nations Food Taster because we have folks who are not Anishinaabe as part of the community as well, and so the First Nations Food Taster has been a longstanding tradition here at Northern Michigan Universities ever since. The community has come to expect this great meal in November.

So as we were back in the kitchen working on preparing this meal in 2010, you know, the question kind of just came to me in the back of my mind Would our ancestors, if they were here with us today, would they recognize the foods that we're eating as something that they were familiar with? You know we're calling it Native American food or indigenous foods, but would they really see that as something that they were familiar with, and so, you know, we started talking about that? You know, would celery soup over wild rice? Would that be something that they would recognize? You know, would fry bread be something that they would indulge in?

These are questions that we just started asking, and so the, you know, became very, a very interesting topic as we were going through the motions preparing the meals, and then it carried on back all the way to the Center for Native American Studies and you know, sitting around there talking with our colleagues and our students, and into our classrooms, and eventually we decided, you know what this is such an interesting topic, it's worthy of doing a project around it, and so we we could have approached it as a just like an active service learning project or something, but we decided to approach it as a research project, and I think that's like, you know, when you talk about university communities, I think that's what universities are good at, or they pretend to be good at anyway is research.

And you know we're not typically known as a research institution at Northern Michigan University, but we at the Center for Native American Studies wanted to, you know, really do our best job at this approach, and so we approached it as a research project. We got institutional review board approval for it. We said it was going to be a year-long project and we were going to measure it the outcomes on a biological, sociocultural and a legal political level, and I think that's what makes our project somewhat unique among the things that are going on in the food indigenous food movement, and it's because you can really count the actual research projects on maybe one or two hands, you know. Maybe I don't know; maybe you got to use your feet now because it's been a while since 2010.

And so, you know, we looked around at that point in time we said you know, here's what they did over in British Columbia, here's what they did on the Dakotas, here's what they did in Northern Ontario, and so we wanted to incorporate some of those things that these other studies had done, counting the food ingredients, looking at the frequency tables, you know, really getting down to a specie level, to where we're talking about plants and animals that we know, in an Anishinaabe way, as spirit beings. Right, you know, these are spiritual beings, but in our daily lives, we often think of them as food, and so that's. We wanted to approach it in a very genuine way, traditional, spiritual way, but we also wanted to make sure that we did it in a scientific way, and there's no reason why we can't do both, in my opinion.

Andy:

Yeah, absolutely. It was really interesting, like what you just brought up, this idea of how you are qualifying things as indigenous foods and rethinking the relationships between us and those foods, and one thing that you make a point not to include is the GMO pre-Columbian foods. So could you talk a little bit about why you decided to do that and maybe some of the qualifiers you tried to use to separate that kind of? Really, I don't want to say gray areas, but things that people might get a little confused about as to whether or not it's quote-unquote indigenous.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah. So we, you know, identity and food is a really interesting area. I'm doing a presentation on that soon for another conference. But you know, first you have to say, okay, well, what is it that makes something indigenous to a place, Right? And so the food in and of itself has relationships. You know, some of these foods were here in the Great Lakes region for hundreds and thousands of years before humans ever interacted with them. So the food has its own identity. And then you have this identity of the indigenous peoples with the food. It's kind of like you can come at indigenous two different ways.

There's the food by itself and its relationship and its own identity. And there's this people's identity with the food, the indigenous people's identity with the food, when we think of it that way. So, for instance, you know the Mallard ducks. Mallard ducks were in the Great Lakes region. Regardless of whether humans being here or not, they had this relationship already established with the other plants and animals. Humans come along, and we bring corn beans and squash with us. So corn beans and squash are introduced to these other plants and animals because of us as indigenous people. So we have this pre-colonial indigenous relationship that kind of focuses on those two aspects.

Well, around 1600, 1602 is about the earliest we know that there's a direct interaction between native and non-native people in the Great Lakes region over by Montreal. So we set our date for the decolonizing diet project at 1600. Give us a couple years of cushion. We know that it takes a bit of time for cultural diffusion to happen, for foods to drift from one across one cultural boundary to another, and so we felt pretty comfortable that anything that was in the Great Lakes region prior to the 1600s would have been familiar to our ancestors, at least somewhat. So we made a decision to base all of our eligibility criteria on that date, whatever was here pre-1600. And then we called them the things that were native, pre-colonials, and then their derivatives, so things that have since, the subspecies or whatever the things that we've derived from those things.

What we did not include, however, is colonial foods like pork and oatmeal. You know those things came with colonists. Even though many of us probably enjoy ham, or, you know, a good bowl of oatmeal, we did not include those as part of our decolonizing diet project. We thought it was important to separate those. We also did not include anything that has been genetically modified, whether it's a native species or a colonial species. We think of those as Frankenfoods. They've altered them.

If nature alters it, then it adapts to the local circumstances. It's something that is happening in a good way, in a way that I think it's to us in Anishinaabe's perspective. It's a much more respectful relationship with Mother Earth and her spiritual beings that exist here. To force something on another being and to change it so dramatically just seems very disrespectful, and the jury's still out on a lot of the health effects of doing that. In fact, we know from some of the laboratory studies. You know that it's having ill effects even in the laboratory before they feed it to humans.

We know that when they feed it to rats, the rats are having unfortunate circumstances, and some of the foods have even been developed in labs as poison. As poison, I mean, think about that. You know the Monsanto corn that people eat. You know it had to go through the poison; whatever that laboratory is that they clear poisons up. So it's really important that we think about the food we eat in relation to their eligibility as indigenous foods or not.

Andy:

I want to talk a little bit more specifically about the study itself. So what I thought was really, I think, the most impressive, and I know you went through it personally, is the fact that you had these different levels of indigenous food consumption, and I'm assuming you volunteered yourself to be one of the folks doing 100% of an indigenous diet. Not only was the project itself like a really good reflection of your dedication to what you're doing, but the results that you reported were also like insane, like in terms of like the health benefits considering, like you weren't like counting calories or any of these, you know, going low carb or any of these like fad things that people say like this is how you lose weight.

So could you talk a little bit about this and maybe some of the psychological effects this diet had on you?

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, so you know, going back to the research participants, we like to use the term participants versus subjects because you know it's much more respectful. Again, subjects seem so cold and impersonal. Sure, so we chose to use participants, and I decided that I was going to try to be the best example, lead by example. I think we're seeing that right now with Ukraine and the president in Ukraine leading by example. What a brave individual, anyway. But I think that's what I tried to do with the Decolonizing Diet Project. If I was going to ask other people to do something that significantly altered their lives, to eat indigenous foods for one year, I wanted to be the best example. I could be led by example. So I chose to be 100%, and it was a heck of a commitment. I mean, it literally altered our cupboard space, our refrigerator space, our freezer space.

A very huge commitment of time for going out and accessing and processing and then preparing and eating and journaling and everything else that came with it the health checks and everything. We required people to be committed at a 25% to 100% level on a daily basis. So a lot of folks were between 25 and 99%. Some folks just didn't think they had the time or the resources available. They didn't have the knowledge, so they chose a lower amount. We also asked them to if they chose whatever level they chose to eat at besides 100%, to eat higher than their percentage when and if they could that way, if there was ever a time when they couldn't maintain their you know, whatever commitment level, then they would fall back to their commitment level. So it was kind of like, you know, commit at 25%, eat at 50%. So that way, if you have to fall back, you're not falling below the minimum.

Andy:

Yeah, you're not going to a graduation party and losing all your gains, right?

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, so I mean. Things happen. You know life goes on, so you try to eat at a higher level, and we also ask them to get regular health checks. We ask them to get an annual physical before and after, then quarterly health checks during, and to work with their doctors, whoever their health advisors were, to increase their level of physical activity. We know that the American diet and the average American amount of physical activity per day is probably rather low compared to that of the indigenous people who lived here prior to colonization, and so we wanted to increase both of those.

The things that we were able to report at the end of the decolonizing diet project year were really cool. One is that everyone who participated in the project lost a significant amount of weight. We also had, on an individual level, folks who were able to decrease their amount of bad cholesterol, whether that was LDL or triglycerides, and some folks were able to also lower their blood glucose level and their blood pressure. So you think about this. Three of the primary killers of indigenous people for years have been obesity, heart disease, and diabetes. We hit all three of them with our decolonizing diet project, so we're very happy with the results, just simply altering the way people eat and encouraging them to do a little more exercise. And you know we have something that you know is going to be very helpful for folks if they truly embrace it and bring it into their families and their communities.

Andy:

How did this diet affect the psychology of folks? Did you notice people were more aware of where their food was coming from, the seasonality of some of those foods, and what were some of the feedback you got? That wasn't as easily measurable as weight and blood pressure.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, so we kind of put that under the sociocultural category, and you know, folks, when they were interacting with the foods, sometimes they were going out and learning new things. You know, people who had never gardened before were gardening. People who had never gathered, you know, gone out and looked for berries, were doing that. Some people hunted and fished for the first time in their lives. But everybody learned how to be better shoppers. I mean, it's amazing when you really truly look at the labels in these stores and what the labels tell you or don't tell you. And so we became very good at that. In some ways, we increased our hypersensitivity and awareness to the world around us in an indigenous food way, and so I think that the lessons that people learned, the community that was created around the idea of indigenous foods and health, really were so positive.

We have folks now who participated in the decolonizing diet project and who have become lifelong friends. That's awesome, and you know when we've lost one. You know, when one of our DDPers passed on, it was a time when we felt a great loss. We became family, and so you can imagine the psychosocial implications of being able to say that we are a DDP family, that we bonded in a very strong way over the idea of eating together and helping each other become healthier people, and that included both native and non-native. So think about the implications of Native and non-native people working together on a project that actually creates this kind of family unit. That's healing, man, that heals like generations.

Andy:

Did you see any statistical differences for indigenous versus non-indigenous people with, like, how the diet impacted them? I'm just kind of curious. As you know, we always talk about this idea of how our bodies are designed for X, y, z, and if having spent 10,000 years eating these foods allowed indigenous people to benefit more from them. Did you see anything like that, or is it just basically, across the spectrum, pretty equal?

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

On a biological level, we've seen relatively similar outcomes for both native and non-native people, and that does not mean that non-native and native people don't have some particular issues.

That being said, genetically, we're not really that different. Sure, you know, we might have certain alleles in our genes that are different based on our ancestry, but ultimately, we're both human, and so the real question is, what kind of diet were these humans eating before the DDP? And I would venture to say that both the Native and non-Native people were eating this very American diet, midwestern American diet, yeah. So it didn't surprise me that both Native and non-Native people benefited positively together.

On a biological level, obviously, they were eating a lot healthier than the average American diet, yeah. On a sociocultural level, I think is where we've seen the real difference. Native people identified deeply, historically, and spiritually to these foods. These were the foods of their ancestors. The non-native people didn't have that deep of a relationship, right? Their relationship with it goes back only so far, and so I think the identity question again came in to impact that relationship. Foods, you know, this is what we've our bodies, in a spiritual way, want these, right, we, we crave it, and so I think there was like this, uh, difference. It was a big difference for native and non-native people and how we approached it.

But I think the non-native people are also very respectful, you know they. They are also looking for rootedness, for grounding, for belonging, yeah, and I think that that relationship that they forged through the Decolonizing Diet Project was a very healthy one, although it's different for them than it is for Native people, but I think it can be healthy for both, for different reasons.

Yeah, and then, of course, on a legal and political level, there's also a difference of rights. Indigenous people, if they belong to tribes, if they're tribal citizens, in other words, they may have aboriginal and treaty rights that are different from non-native people. Non-native people also have treaty rights. You know just the fact that we have a state of Michigan, is you know, and that Michigan allows its citizens to go out and hunt, fish, and gather in its way under its laws. That's based on the treaty. So we have treaty rights. On both sides, there's a difference of rights, and so it's where those rights come from. Again, our rights come from our indigenous ancestors. Non-native rights may come from British common law and this kind of nuanced American democracy.

Andy:

So I think it can, again, it can be a healthy cross-cultural relationship and amalgamation of indigenous and non-indigenous cultures, doing really kind of the best of both worlds about, like decolonization is you know the emphasis, I think, like on the internet is like, okay, we have to work to help indigenous sovereignty exist and so on and so forth, and those are all really important and necessary conversations.

But then when it's like, okay, what about the white people? Where do they fit into this? Like we can't go back to Europe or, you know, something like that, so that, so how do we make amends? And that's the part I think people just really struggle with. So this is a really interesting way to address that and to allow folks to find someplace in respects to the indigenous people around them and in many ways, together but also separate. It's really a beautiful idea.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

I always tell people the decolonizing diet project was not about sending white people back to Europe or wherever non-Indigenous people are from right. I can't do that. I can't just simply cut out things from my life that I have a place in my life now that are part of our identity here. You can never undo decolonization entirely. It has forever changed this land. So the act of decolonizing is trying to become healthier in the land that you're in.

As Dr Robin Wall Kimmerer, Anishinaabe ethnobotanist, would suggest, love your mother wherever you love her, wherever you find her, wherever you find her, right? So a mother earth, really, wherever we live, we love her here in a local way. You know when we're talking about music, for instance, I love Pink Floyd and I'm never going to say I can't listen to Pink Floyd because they're from, you know, England or Great Britain. You know what I'm saying.

So it's like, why would we do that? And so, the act of decolonizing is giving us an opportunity to rethink and to recenter. It doesn't necessarily mean that I don't eat Chinese food anymore. Right, I think Chinese food can be very healthy, very good, and when you mix it with indigenous food, like wild rice, my gosh, sometimes it's really tasty and healthy. And it's not saying that we have to get rid of everything non-indigenous, but what it is saying is give us a break.

We've been colonized for over 500 years, you know. Let us take a minute, take a breather, and think about how our ancestors had it. What was so cool about the way they lived? And try to renegotiate, renavigate through this. What happened is a process of colonization. So much was disenfranchised we were disenfranchised from. Just give us an opportunity to think this through and to think about what would be the healthiest way to move forward if we had had that opportunity back then. Yeah, maybe you know, maybe we choose to keep things like Pink Floyd, but maybe we get rid of Kid Rock. You know, maybe there are things that we keep and things we get rid of, for whatever reason, but those, those we have to give ourselves that opportunity, that space to renegotiate and recenter our identities.

So I think that's what decolonizing is really about. You know, the healthiest way that we can eat as human beings is locally and indigenously. So why would we not want to do that? I mean, if that is truly the definition of healthy eating for not just ourselves but the world around us, why would we not want to do that?

So, you know, wherever we go, if we happen to find ourselves going from here over to Australia, well, maybe we take some of our food with us when we go there, and we share it, but we certainly don't try to displace it. Yeah, right, that makes a lot of sense, and I think that's the disrespect in the relationship that happened as a part of colonization, the oppression of food systems.

I think that's why, when we're saying decolonizing, what we're really saying is you know, let'’s recenter this and rethink it so that we can approach this in a much healthier way for all of us. This and rethink it so that we can approach this in a much healthier way for all of us.

Andy:

I think it's really easy, especially like on the internet, to go down these really dark rabbit holes of like culture wars around us versus them, that isn't really engaged in an attempt to make things better but to be more right. And that's why I like talking with folks doing stuff like this, because it's like I'm working to show a path forward, as opposed to being fixated on what's the perfect thing that was not really realistic, but it is something that I can say on paper, and if we can't have this perfect thing, then everything else is terrible. It's important to provide solutions or work towards those solutions.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

I'm a mixed ancestry Anishinaabe Ojibwe. I have relatives from Ireland and France. I may not have grown up as Irish or French. I grew up as a mixed ancestry Anishinaabe Ojibwe person from this side of the border between US and Canada. But that doesn't mean that I hate everybody else. I can't hate myself just because I carry the genes of people from Ireland and France. What I do expect is that people as individuals recognize that on a collective level, right, not as individuals.

Andy, I don't suspect that you made a conscious decision to colonize the indigenous world here. Yeah, no, but on a collective level. Certainly, the country that you have citizenship in did right, and so, on a collective level, that country still exists; it's still a colonial country. As individuals, we have to come to grips with that. I have ancestors who are colonists. You know that they were part of that process, that I would support what they did, just because they were my ancestors.

I think it's important that we right the wrongs, that we address those original sins and that we, you know, make this world a better place for everybody, and if it's within our own families and our nations, well, when we have to heal them, yeah, you know, the healing happens for both the oppressor and the oppressed. You can't just heal the people who have been hurt because oppressors don't know that they're also hurting themselves just by literally being oppressors, right?

Andy:

Well said. So we've started talking about this bigger picture conversation of how decolonization plays into food and thinking about paths forward, but I do want to ask a little bit more about the specific diet itself that you were eating. As part of this process, I was looking at some of the charts in terms of the foods that were being consumed on average, and it looks like I believe the most, the highest quantity food consumed was maple sugar, which is really interesting for a couple of different reasons.

So obviously, in the Great Lakes region being a cold place, maples are everywhere, and you're going to have a lot of maple syrup or maple sugar if you granulate it. But also it's a sweetener. You would think it's terrible to have a diet that's like majority white sugar, but despite it being a majority different sugar, it's still really healthy. So I'm kind of curious about your thoughts about that.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Well, I'm a maple-aholic man. I like my sweets and that's, you know that's the number one. Of course, you know we have other things that are sweet to the berries, even inulin powder that comes from Jerusalem, artichokes, right? So I mean, there are a lot of ways you can sweeten your foods, but Maple is absolutely one of those ones that's a real cultural icon here. You know we are woods people in this area, and, like the Keweenaw Bay Indian community, they were the largest producer of maple products in the world for a long time, you know, until, of course, they were disenfranchised from their traditional subsistence patterns. So I think there are people like my friend Jerry Jondro; you know they're making their way back to that, to revitalizing those traditions in their community. You know we have a range. I always say that we have this range of tastes, you know, in the American diet.

The American diet is made up of, like every other culture in the world, right, and you can find everything. You go to New York City, you can find every kind of food in the world there, and so the American diet is like, the spectrum of foods that you can eat is this broad and I'm only holding my hands here because you can see it on the camera, Otherwise it'd be way out there, right.

But you know the Anishinaabe traditional diet. It's not that broad a spectrum, you know. In fact, it's probably like that. But when you really get into it, it's this deep, right, and so you get this spectrum that only goes so broad for Anishinaabe traditional foods. But then, when you start really looking at what our people did with it, it's that deep, and you know most of the American diet. I think we probably get about that deep into it. You know, when you really think about it, how people explore food that well.

Andy:

So, while we have a wide spectrum, we don't and I'm assuming you're talking about this idea of like how to utilize it and like the different ways that it can be utilized yeah, like you know again, jerry jondro, my friend, he just sent back some blueberry maple vinegar with my daughter when she went and visited with him the other day.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

And of course, you know, try that with some wild rice casserole, right, like a stir-fry casserole type thing. I don't know what you call it, but you know, it's just the experimentation of food. You know, trying different things together, uh, trying these things, and then, you know, always coming up with these new tastes and in utilizing, truly utilizing what exists in the world around you. You know, the intimate relationship that we foster with the plants and animals around us makes us more respectful of them. But in turn, they love us with their tastes, right? They love us with their nutrition. They really give of themselves, literally, right, their lives to support us. And some of those tastes you just won't find anywhere else: Ground cherry, ground cherry syrup.

Have you ever had ground cherry syrup from Gwynn, Michigan? It's amazing. And I don't know; maybe it tastes different from ground cherry syrup from I don't know Mount Pleasant. So I mean, we have to really taste our world again. Robin Wall Kimmerer says that every day, every day, we should at least have one thing from the world around us. We should consume it to keep that connection so intimate with our place.

Andy:

Yeah, it was just really interesting, this idea of the utility of something as simple as maple products. So you think, all right, I make maple syrup, can have pancakes. That's basically what most s, you know, waffles, pancakes, and that's about it. Yeah, but making it almost like I think it was about 35% of the total calories consumed is just like. ’ is just like. It speaks to that ability to be creative with it.

One of the other things that stood out to me when I was looking through the data you guys presented is that, despite having access to something like bison, which you can buy on the shelf fairly easily, it wasn't a really big focus of people's diets. And I really thought it would be, because it's something that's fairly accessible. People know how to cook beef, so the idea of, like, okay, well, it's bison, it's basically like cooks the same way. It's a little bit leaner, but I know how to make a burger with no bun and put it with some rice or whatever it might be. I'm interested a little bit about it.

I'm assuming that part of this was providing materials on how to cook with the various ingredients, but was there a focus on like, hey, don't just go replace white rice with local rices, local wild rice? Don't just replace your burgers with, you know, bison or any of those types of things.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, so when we started out the beginning of the year, we had to teach people how to identify indigenous foods, of course, right. And so most people were going to the local supermarkets, and that's the way they were accessing their foods, and so there was a lot of that. It was like, okay, well, what can I do instead of this? And so we would say, well, why don't you try this? But then they didn't know how to cook it. So people would get bison and they would, you know, they would overcook it, and then it'd be very dry, because there's not a whole lot of fat content, it's very lean, and so you have to, you know, do a little bit of experimentation.

You know trial and error. If there's one thing we're good at as humans, it's making mistakes and learning from our mistakes, right, yeah? So I think that's the. It's part of the cooking process learning how to cook these indigenous things, yet again, because a lot of them are foreign. The native is foreign to a lot of people. So I think there is that. The other thing is that we held these potlucks. Once or twice a month, we would hold potlucks and we would ask the participants to bring in something that was indigenous, and we always asked them to bring it in 100% percent indigenous, so that we could have a hundred percent indigenous meal together, and when we first started out the year sometimes people would make mistakes.

We'd have to, of course, before I ate it and the other hundred percent are on the diet, ate it we always asked you know what in the what's in your meal? And they would go through, and they would list it out, and then we'd say, okay, well, you did pretty good on that, but this is not indigenous, right? And when you mix this in, that was not indigenous. So there were some things we could eat, some things we couldn't, but people learned through that.

By the end of the year, though, people were really good at that. I would even say by the six-month mark. You know, we were not having people bring in non-indigenous foods anymore, and so they got really good at that. And they also got really good at making it taste good. They were experimenting, they were finding ways instead of just the bland here's a bowl of pepitas with nothing on them. They were really learning how to create and unlock these flavors and using different indigenous spices and really doing some, really doing some things that I think were, might be considered gourmet.

You know, by the end of the year, we had us at the end of the DDP. We had this indigenous foods cook-off and there were, we had three groups that were given five hours with a table full of indigenous ingredients, mystery ingredients, and they were challenged to create a side dish, a main dish and a dessert and, my gosh, it was so cool the things that they came up with. Right duck egg drop, indigenous corn breaded white fish bites with maple vinegar sauce, I mean, just really cool things that you would not find anywhere except like a real specialty restaurant, you know, maybe once in your life. And so we had this really cool thing happen.

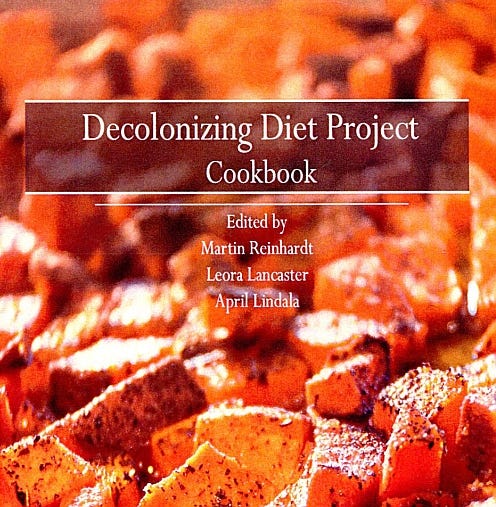

You know, these people who were not really good cooks as far as indigenous foods at the beginning of the year, now cooking these very advanced meals that you see people like award-winning chef James Beard, and so I mean that was really cool, because I can tell you I'm not a chef, I have no training in that, but I was cooking some good stuff, Right, and things. When we went and visited his restaurant, it reminded me of where we're kind of at the end of the DDP year. You know people are really making that kind of advance, so you know that made me feel pretty good. The other thing that we did is we had people share their recipes and their methods in this online forum, which we eventually collaborated on and edited this decolonizing diet project cookbook, which is now available to share with the world. In fact, we've sold almost 2,000 copies.

Andy:

That's awesome. Yeah, I was gonna ask about that book. It's really cool, and I was reading a little bit about it, and you were just talking about kind of where it came from, which is really interesting, like a very. communitive process, and like it ties into a lotves that you're talking about. It works really well, and I think this raises the question of like. Where does all of this go next in terms of like? Is this something that can really be sustainable on a larger scale and kind of? You know, obviously there's a lot that underwrites that in terms of commodification of food and land access and all these parts of decolonization that we've been talking about. But it sounds like, from the way you're talking, you're pretty optimistic about the future of this type of food movement.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, I really am. When you come from 2010 to 2022, and you see the changes that have happened, you know, back then there was, like, like I said, a handful of this kind of projects going on, and the indigenous foods movement in general was very young. Today, it's like a tidal wave going across the world. Indigenous foods is the trend. It's where people want to be. That can be both a good and a bad thing, though, because, on the one hand, it's doing a lot to revitalize these traditional food systems.

We're getting a lot of support from grants and interest from individuals, such as people buying books and wanting presentations. So that's a really good thing, but we have to be careful, too. We don't want indigenous foods to become the next Taco Bell. I mean, we don't want people appropriating them and calling them something that they're not.

We don't want people appropriating it and calling it something that it's not, so we want to maintain the integrity of the idea. We want to be respectful to the core. We don't want to be sending our indigenous food products 10,000 miles away and inflicting the same harm on Mother Earth that we're seeing happen with other foods, so we don't want to be part of the problem. We want to be part of the solution, so it has to come with an ethic. It has to come with an ethic where we honor and respect Mother Earth, and we say, if we're going to have indigenous foods, then we're going to have it in a decolonizing way. You know, the worst thing that can happen is you have a whole bunch of people who have no relationship with these foods whatsoever other than going and sitting in a fast food restaurant and consuming them on the other side of the planet.

Andy:

Yeah. So, Marty, for folks who have enjoyed this conversation, where can they find the book? They want to see more about your studies. I know you teach some classes on similar topics. If you could, could you tell people where they could find that interesting information?

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Yeah, so, uh, we now offer a course at Northern Michigan University called decolonizing with indigenous foods, and so we'll be offering that every summer in the months of July and August. So that's one way they can learn more about that. Take the class. It's an online class, and they can do it from wherever they live. And the other way is to, of course, get the decolonizing diet project cookbook, and you can find that either at the northern Michigan university bookstore or the center for native american studies on campus, or you can look up Reinhardtassociates.net, and I sell those personally myself at our website. You can also join the facebook site.

Our Facebook site has over 6,000 members. It's probably the largest indigenous foods Facebook group out there. So, just, you know, Google, decolonizing diet project, Facebook and, you know, sign up. The only time I've ever told somebody they can't be part of it is when they start posting, like, you know, advertisements for selling vacuum cleaners or something, as long as they're respectful of the site, you know, and then maintain the integrity and respect.

Andy:

Awesome, Marty. This has been great. Thanks so much for coming on.

Dr. Martin Reinhardt:

Thank you.

To listen to this interview, tune into episode #107 of the Poor Proles Almanac.

👏 “how to eat as people on the landscape ate in the past… to integrate this past with the present” as locavores.