Protecting America's Last Wild Buffalo: Indigenous Advocacy and Ecosystem Restoration

The following interview was recorded for the Poor Proles Almanac podcast with guest James Holt, from the Buffalo Field Campaign. If you're not familiar with the Buffalo Field Campaign, they're working to protect the last of America's wild buffalo. Since 1997, they've been working to protect the natural habitat of the wild, free-roaming bison and other native wildlife, and stand in solidarity with First Nations to honor the sacredness of the wild buffalo. We talk with James about his work, reconnecting indigenous people with these wild buffalo, and the role of the government in trying to divide indigenous groups against the best practices for these buffalo.

Andy:

Thanks so much for speaking with us. Please introduce yourself to our audience.

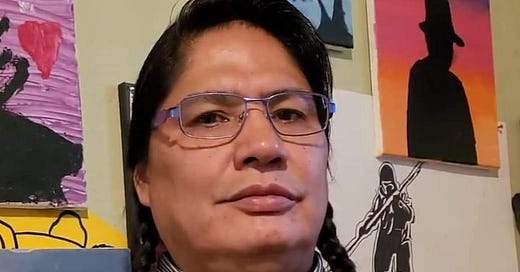

James Holt:

My name is James Holt. I'm the executive director of Buffalo Field Campaign. We are the only organization in the field, monitoring and bearing witness to the mismanagement of North America's only continuously wild herd of bison every day of the year.

Andy:

Can you tell us what a buffalo is, versus the bison we might buy at the grocery store?

James Holt:

Well, bison, you know the scientific name is bison bison. This is the original plains bison, which was almost eradicated in the 1870s and 1880s, versus its woodland cousin found in northeast Canada. The woodland bison originates from that area. It's a little smaller, the horns are a little narrower, versus the big, massive bodies that you get out there in the plains. You know wild bison, sure, you know these herds are important to us because of the 23 bison.

These herds are important to us because of the 23 bison that survived the slaughter. They were from where the central herd of bison is in Yellowstone National Park, and so all the bison that we have, almost all of them, come from there. It's the indigenous species that have always been located there in this area. As an enrolled Nez Perce man, that area of central Yellowstone is also ancestral grounds for my people, and so that's the tie that I have. And why I chose to be a part of this organization is because of its mission and how it aligns with my own cultural life ways.

Andy:

That's amazing that some survived and that there are so few. It's astounding that somehow, you know, there's this tiny, tiny genetic pool. That's like rewilding, I don't even want to say rewilding, because that's not the right word, that's helping a population return to a landscape from such a narrow pool. It's unbelievable.

One of the terms I saw on your website is the idea of a 'beefalo,' which I think is probably just a really interesting term. It's the idea of creating a hybrid between bison and cattle to essentially produce a fake bison, allowing them to sell expensive beef at the store. I'm curious about your thoughts on that kind of work and how it might impact or be detrimental to what you’re trying to do.

James Holt:

You know that's a good question. Bison restoration has various interpretations among people in this realm. The Buffalo Field Campaign, wild is the way for us and the only bison that live without borders, besides that of the National Park, which is a travesty and kind of at the heart of our mission. They're the only ones that do not have a fence, aren't obligated to vaccinations, and aren't subject to the corralling and other steps that take place, even within the wild genetics that are transferred, for example, through the Fort Peck program and then restored to tribal lands. Those bison then become products of initiating the domestication process. So even the wild bison that are restored to tribal lands from Yellowstone inevitably themselves show characteristics of domestication, and so the beefalo industry and all of that.

You know there are 500,000 bison, so to speak, throughout North America, and there are only 5,000 wild bison. So there's definitely a huge differentiation. People are treating all bison as wild bison and we know that's not true. These other bison, beefalo, definitely show signs of domestication. You know they act that way, they're docile, they're definitely more domesticated than the wild counterparts, and there are a lot of traits that separate the two.

Andy:

Yeah. So do you think the development, and I guess the media around, like you know, oh, I'm going to have bison for dinner, and like how that's portrayed, do you think that's a good or a bad thing for what you guys are trying to do? Do you think it raises awareness, or do you think people are now less concerned about it because they feel like they see it on the shelves all the time?

James Holt:

It's a public relations campaign, as Yellowstone National Park itself acknowledges that we have too many bison here and need to cull.

This year, we're culling six to nine hundred, and if we achieve nine hundred, we'll consider another 200, literally 20 of the wild population. When there's an entire ecosystem out there, they're the ones that control the media.

You know we're small fish compared to the imprint that they have and and so definitely they're carrying that message where there is no short supply of bison, because you can go into the store and buy it for a pound of it and eat it at home, without saying that it could be organic, it could be grass fed.

However, it's still raised behind a fence; it still has all the characteristics of domesticated livestock. You know, it's very difficult for us to get our message out there and to counter that strong platform that the Park Service and the state of Montana enjoy. The only way that we can elevate this issue on our behalf is to win in the courts. You know, exercise our on-the-ground relationships with these herds and show the travesties of this mismanagement to really orchestrate that what they're saying is not true, and hopefully we get enough heads turned our way and enough attention given to us where they can start carrying that message and hopefully people will start listening.

Andy:

Yeah, and that's why I wanted to talk to you guys. You brought up Yellowstone National Park and how they're managing the bison. Could you provide more detail about that?

James Holt:

The Park Service has been managing the bison within the confines of its authority, which is to say, within the park boundary. Their biologists have delineated that there is only one distinct population of bison in Yellowstone National Park.

We, through our own observation and our understanding of the science, the Buffalo Field Campaign asserts that there are two distinct populations, and the central herd of bison is ailing. In 2011, they decimated the central herd by killing over a thousand animals. The herd has never recovered, and so, if the Park Service says that there is only one population, 3,500 animals is considered the baseline to ensure genetic diversity within that population; we keep winning in court.

We ascertain that there are two populations, with 3,500 failing, combined between the two subpopulations, and a much larger population is needed on the ground. They must access historic migratory pathways, fulfilling their historic role within the ecosystem as a keystone species. This must be done not only to honor the buffalo, but also to celebrate the landscape and build the resilience we want into the ecosystem itself against climate change and human-caused ecosystem degradation. We're seeing all these things on the ground, and bison are key to reversing all these trends.

Andy:

With the bison in Yellowstone Park. Are they allowed to leave, or are they actually fenced in, Bison?

James Holt:

There are no boundaries, there are no fences, but the fences of the agents themselves. There's hazing, there's quarantining. Over the last six years, the US Fish and Wildlife Service has gradually expanded its presence into areas where treaty hunting, or hunting in general, is permitted. So they've created these canned hunt conditions right at the park boundary. So, in essence, the canned hunts divert public attention away from the heavy-handedness of the managing agents themselves, and they place that on the hunters.

And it's a, you know, a misnomer to say that the hunters themselves are causing this, when it's the outcomes of these managing agencies. So the park service manages the population, with Montana in mind. It's Montana that's obstructing the expansion and the ecological restoration of bison through the landscape. So the Park Service has, in essence, kowtowed to Montana's assertions, and that's something we've fought also, and the writing has been on the wall.

The myth of brucellosis that managing agencies use as a pretext for slaughter primarily stems from a conflict over the land north of Yellowstone National Park, where the Forest Service seeks to create a landscape conducive to cattle grazing rather than preserving the ecosystem for wildlife. We contend that the ecosystem itself is more important for our future generations, as we will need those ecosystem services, and currently, it's not the case.

Andy:

Yeah, I agree with you on that. When I was reading about some of the issues you had positions on, you had done an open letter about the hunting of bison. I want to ask a few more questions. I know they have these slaughters where they come in and cull the herd, so to speak. At least, that's how it was presented in the different articles I had read about it. Those bison went to feed indigenous tribes, but the way you're describing it sounds a little bit different.

It sounds like you are interested in indigenous rights, to be able to hunt bison on tribal lands, and things like that. What is Yellowstone doing in this hunting process versus how you envision these things should be happening?

James Holt:

The tribes themselves as signatories to the interagency bison management plan and the process of developing the priorities within that plan. There are a few treaty tribes that have a seat at the table the Nez Perce tribe, the Confederate tribes of the Salish Kootenai and the Inter-Tribal Buffalo Council. So those three tribal entities have a seat at the table. The Nez Perce tribe, of which I'm a member of, has been calling quite loudly for an ecosystem-based population management for the Yellowstone, understanding that the park is not the ecosystem it's, but a part, a piece of it.

And so, what I've witnessed the Nez Perce delegates representing is that they want an ecosystem-based management plan. For them, there is a solidification or consistency in their treaty rights, which are a precursor to their cultural life ways. That relationship is strengthened by having bison proliferate the landscape, and it's also built upon this sacred responsibility that we have as a hapten people, the Columbia Plateau people, which is rooted in the notion called tamalwit. It's a sacred responsibility that was bestowed upon us by our maker when he brought us into this world, because we know that we came after the rest of the world.

And so the creator brought the animals together, and he asked them what they would do for the human beings who were coming. So, all the animals got in line, and they told the creator what they would give to the humans. And when all the last animals, trees, bushes, insects, all went through the line, he told human beings what they would be given. And he told us that we had our sacred responsibility to speak for those things, to act and honor them, and respect them. And so, in this process, it was the following persons who came late into it that had to assert their treaty rights to then begin that cultural, spiritual, and sacred relationship with the bison, which was to speak for them.

And they see that the Park Service is not their only home. It's a part and parcel of federal Indian policy throughout history, and that's to force us onto the reservation to minimize our numbers and manage for scarcity. And so we still see that proliferate through to today with bison management and that indirect connection that they're forcing tribes to have as a relationship with bison. And so tribes like the Nespers are saying they want that in a bigger way, they want to satisfy that sacred relationship as it means to them, as they were promised in the treaty.

And so, it has added a different dimension to the entire planning process, which I believe is why Yellowstone National Park has initiated a new environmental assessment to create an environmental impact statement, establishing an entirely new bison management regime for this Yellowstone population.

It's taken a while to develop, and I hope that it's based on the Buffalo Field Campaign's decades-long advocacy, which has shown that this heavy-handed management has an impact.

I mean, we've seen years where they've got, they've finished their hazing, their quarantine, their ship to slaughter, and we've seen clan herds come out with yearling bulls leading calves, five calves, and that was the herd now because so many had been killed off and it was horrible to see.

We've seen them forcibly kill the ancient migratory knowledge of those clan mothers to take their babies out to the calving grounds, to take them to the early exposure grass grounds, where they increase their chances of survival. And so we've seen and witnessed the Park Service, the Forest Service, and the Montana Department of Livestock create these conditions, yet they act as if they now create the change that's needed. Frankly, the alternatives proposed in this new process are still falling short.

It's up to us to hold these agencies accountable to ensure they do create the change that's needed, and frankly, the alternatives that they're proposing in this new process are still falling short, and so you know we have a lot of work to do. You know the bison, the wild bison, deserve a place, and it's, it's not, it shouldn't be them or cattle, and you know we're seeing that too often within the Forest Service. You know, we can talk about the tule elk over in Central California on the coast, or any nature of cattle versus wildlife, and the Forest Service is on the wrong end of history.

Andy:

Yeah, the government tends to do that.

So I have a question that's a little bit related but a little bit outside of the scope of this, but I was thinking, as you were talking about this, that you brought up this fact that it sounds like they're transporting these buffalo for slaughter the same way you would do like cattle. Is that correct? Is that because of like FDA regulations, or is this an explicit attempt to disconnect indigenous tribes from those animals?

James Holt:

It's definitely both; it's a legacy tool of the Department of Livestock and Forest Service, which has led the way in the past few decades. Early on, when slaughter was very heavy, they were the ones who did that. Over time, the tribes screamed loudly, and now they have what is called the Fort Peck program, which is located on the Fort Peck reservation, north of Yellowstone National Park. I believe the quarantine for slaughter is almost at an end because they have so much land available to house seronegative bison to be restored to tribal lands.

That's minimizing the number of bison for slaughter. But still the positive bison are sent, and you know some go to tribes, some have gone to tribes historically, not all tribes. They play favorites. If you agree to the slaughter, you get animals. So they have mechanisms to address low-hanging fruit for some tribes that face extremely harsh economic conditions, while others lack a connection to bison at present. They'll be quick to accept them. So they're. They have ways to create diversion, disconnection, and conflict amongst parties that should be seeing eye to eye on these issues. So, it's divisive and layered.

There will be a lot of restoration in other places. The places they're going to be restored to, they're obligated to manage those bison as livestock, as domesticated animals, and so, once again, they get accustomed to human interaction. They begin the vaccination and annual inoculation process. They're used to feed, you know. They get fed hayulation process. They're used to feed, you know. They get fed hay and oats. They're behind fences. So again, there's only one way to have wildlife and that's for wild to be free to do their thing, and that's not it for us.

You know, For better or worse, yeah, we want the ecosystem saturated first, but it's not a zero-sum game to us either. We see that they can be both. The Buffalo Field Campaign has been here for a long time and has seen which tactics and tools work better than others. We've observed that these zero-sum games, where everybody is competing, are a false narrative.

You know we can find the internet's great at that. We can find common ground and we do want to have allies, powerful ones, like tribes who are just trying to reconnect with their cultural life ways, whether that's subsistence hunting within the Yellowstone ecosystem, as preferred by the Nez Perce tribe, or with a strong on-reservation herd that tribes like the Blackfeet Nation, Fort Belknap you know these other reservations want, you know, and require on-reservation herds to, you know, provide for that subsistence needs, those dietary needs on reservations.

There is abject poverty. You know that is the nature. Even here at Nespers right now, we probably have a 30- 40% unemployment rate. You know, we're a third-world country out here, so we have these needs for our diets. You know we need bison, so those tribes do need to supplement their diets. They do need the economic development that comes from the value-added products a bison herd represents, as well as the cultural ties that the reunification of bison means to those peoples. So it has all these different layers, but none of them are zero-sum to the needs of the ecosystem in Yellowstone.

And that's our message. We don't deny that tribes have vast and significant needs, but so do the ecosystem and the land; we are at the 11th hour. We have been told that time and time again and we have to do it. I'm a spiritual man and I go to those arenas as well. It's frightening to hear our medicine people talk of the prophecies that are coming, the time that's approaching us. It's the climate science that the scientists are telling us the thresholds that we're achieving through carbon dioxide in the air. Our spiritual leaders see this, and they're seeing it, and they're telling us, and it's scary, and we have to prepare. Bison and the ecosystem are a powerful tool for building the resilience that we and our unborn generations will need.

Andy:

You know, we hear stories, at least in mainstream history, of like having like tons and tons of bison across like the Midwest. Still, their scope was so much bigger than that; we have evidence of them being present across the entire country. As large as they were, they had a significant impact on the ecosystems.

There's a few papers that came out recently talking about the Eastern Agricultural Complex and how, while we think that a lot of domestication for like May grass and all these other plants was because of the flooding around the rivers, but also a lot of those early domesticated species are found basically following the bison, so that there might have been these multiple venues of which domestication of plants started. Those bison were not only an animal that provided food for millions of people, but also were a driver in creating the ecosystem that allowed people to thrive. And I think there's just so much we don't know because that history has been disconnected from us through colonization and things like that.

James Holt:

Yeah, it's the oral histories we know as indigenous peoples, but it's very interesting to see that science come to the fore now. There's a recently retired biologist from the National Park Service who wrote about this phenomenon. He's witnessed and studied over his tenure at Yellowstone National Park. Is bison creating what's called a green wave. Through just the way they forge upon the landscape, they make this entire wave of revegetation by entire plants on ecosystems, on a landscape scale, which brings the insects back, which brings birds back, which I mean it has such a benefit to so many other species that it's hard even to quantify.

Andy:

Now, the thing I really struggle with around this idea of bringing bison back to a massive scale here in the United States is, how does that work? Like capitalism, where people own their own little plots of land. There are all these suburbs with like fences up everywhere. I'm not sure if it's because I'm in a very urban area here in New England, but I may have a skewed perception of what something like this would look like. I mean, it sounds like there are tribes that are working with wild populations. Could you speak a little bit about how, if it's realistic to reintroduce bison at that kind of scale, or like what? What are your thoughts about that?

James Holt:

I think it's possible. I've been researching these conditions for some time now, and with administrations like the one we've now, there is a possibility for a monumental lift. We have a Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, who believes in the 30 by 30 initiative, which aims to preserve large landscapes by 2030 to combat climate change. In our view, the Yellowstone ecosystem should be a candidate for that designation, and it would require significant infrastructure funding to achieve it.

We've seen those priorities reflected in the administration's transportation bill, the infrastructure bill, and various wildlife management bills. There is an opportunity to create the necessary wildlife crossings and fencing along essential transportation corridors for wildlife. You know, we can provide the safety measures required to minimize wildlife fatalities, as well as protect our own agricultural interests, our communities, and keep those intact.

There is a way to stage the implementation so that by the time this population achieves ecosystem saturation, we will have incrementally built up the infrastructure to accommodate that growth. There is planning that can be done in conjunction with other facets of our existence, such as infrastructure and informed building within our communities. We can build in the resilience necessary to accommodate the wildlife.

Andy:

Yes, I think it really comes down to reassessing our relationship with ecosystems in a way that we don't fundamentally do today. You know, I imagine like, again, a bison being as big as it is. Here, where I live, there's nothing of that size. You know, we occasionally will get like a black bear that'll walk through town, and that's like once a year, and that's like the biggest thing we'll see.

And I think that for us to be able to grapple with climate change fundamentally, we have to reassess our relationship with our ecology. And this is one of those places where there has to be an integration of our understanding of ecology and giving some flexibility to things like private property and our knowledge of our relationship, of how private property relates to ecologies and the responsibilities that I don't want to say responsibilities, but maybe the willingness to give up some authority on that private property for a greater good.

You're familiar with the ecology, these very important species that are fundamental, as you said, to restoring ecosystems and making them more resilient to climate change. It's a fascinating and complicated convm happy that folks like you’ folks like you are doing this kind of work. You said some new regulations are going on around or they're in the process of developing some new guidelines around Yellowstone, I believe, on bison. Could you discuss that a bit and share your hopes for it?

James Holt:

Yes, so you know they've just initiated an environmental assessment process to reconsider how they manage bison and Yellowstone. They have presented three alternatives. Alternative A or 1, I'm not sure which one it is, but it involves status quo management, aiming for 3,500 to 4,000 bison year in and year out. The second alternative raises the population to about 6,000, with a slight concession toward bison having greater mobility to move around the ecosystem, but still having to stay within the confines.

And then the third alternative bumps that population up to 8,500 bison and has a greater degree of tribal input. Those treaty tribes that have a relationship with Yellowstone bison will have a greater seat at the table. And this is all predicated on bison having to stay within the confines of the park boundary, and so it's a flawed plan based upon that alone. It's still the only wildlife in the region that would be managed in that way alone.

Elk are able to move freely throughout the ecosystem wherever they can or want to. They have transmitted brucellosis to cattle, which the cattle industry considers to be so severe. But there's a huge income generator from those elk hunting permits, so the elk go unmolested. Bison have never given cattle brucellosis in the wild, yet they're forced into this tiny population because they're large enough to contend with the grazing in that forest service public land. So you know our work is not done when this plan, the new plan, still fails to produce the ecosystem services and the ecosystem-based management that we, you know, is only appropriate. You know our work is not done.

Andy:

Yeah, I'm assuming you would like to see more than less with what Yellowstone is proposing. It's an interesting scenario, especially the way they're manipulating the local tribes to get their way, with as little as possible being given up. I have one other question that's outside of the scope of this conversation.

Considering all of the background of this very long and complicated and basically abusive history by the US government around bison, I was wondering if you had any thoughts about, for people like myself, who may be hunters. Would you rather white people basically stay away, or do you see it as like an important financial driver for the tribes, and that's why they're probably partnering up with these folks that can afford to do those things?

James Holt:

Well, I know the hunters themselves stay separate. You know, there's very little intermingling of treaty and non-treaty hunters in the region. Furthermore, I am not aware of any conflict between treaty and non-treaty hunters in the region. Moreover, I am not aware of any conflict between treaty and non-treaty hunters in the area. It's looked upon as more of an American value, a Western value, that opportunities subsist and to provide that subsistence for yourself is a very powerful thing.

And I was the individual who was key to the treaty tribes reuniting with the Yellowstone Bison. It was my research that united the Nez Perce tribe and now all the other six treaty tribes, or seven, that now exercise that relationship. Personally, I feel great knowing that what was severed for us in the 1870s was reunited under my watch. And that was a powerful thing. Because we still utilize our treaty reserve rights as a backbone and foundation for our subsistence throughout the year.

I still can dry and freeze salmon for the year that I catch it myself. I still I hunt moose, elk, and deer. I used to hunt buffalo until I assumed this position and I take this seriously. So I no longer do so, but I still hunt for my livelihood and my wife and my daughters. They still dig roots and pick berries. We believe in this way of life, and we know that other people do too. There isn't a conflict there, and I think people wish there was. You know they try to, as you said. As you mentioned earlier, the media and individuals are really good at polarizing these issues in the hope that they can find a way to drive a wedge, and so far as I've seen on the ground, I've never seen a wedge driven between treaty hunters and non-treaty hunters.

Andy:

Awesome, James. You're doing fantastic work. For those who want to support your work or learn more about what you’re doing. Where do you want me to send them to?

James Holt:

Please visit bufflofieldcampaign.org and sign up for our newsletters. You'll get our updates from the field. They'll start coming out, if not every week, every other week. Right now. They'll let you know exactly what we're doing as we monitor these actions and outcomes of the winter operations plan. This is the hardest time for us where they do all these heavy-handed management actions. So, watch us see what we're doing. Every month, I issue an "On the Buffalo Trail" publication that outlines the issues as I see them over the last month. So we have a lot of things. Follow us on Instagram. Follow us on Facebook.

Andy:

And I'm sure those handles are at Buffalo Field Campaign. Yes, they are Awesome.

James Holt:

Follow us and stay up to date with these issues. Our grassroots supporters drive us. They're our backbone. They are the wind beneath our wings.

Andy:

Awesome, James, thanks so much. This has been great.

To listen to this interview, tune into episode 110 of the Poor Proles Almanac.