Revitalizing the Scythe

How a simple tool can connect us to the land, the past, and our bodies

This piece is part of a collaboration and written by our guest author . Go check out his substack for more fantastic writing in this area!

Introduction

“Our tools are better than we are and grow faster than we do. They suffice to crack the atom, to command the tides, but they do not suffice for the oldest task in human history, to live on a piece of land without spoiling it.”

-Aldo Leopold, “Engineering and Conservation”, The River of the Mother of God

As builders, crafters, farmers, stewards, and mere humans, our relationship with tools is everything. They are forged in an attempt to make our work efficient and effective, and that process can lead us down the path to becoming active participants in our material surroundings or passive operators of machines that obscure our connection with larger systems. The scythe, an ancient fixed-blade tool that has appeared in various permutations across many cultures, is an implement that has in the past and also now in the present can lead humanity toward the path of ecosystem connection.

What is a scythe? It is a single-beveled edge, clamped to a wooden handle with a few screws at most. It contains no moving parts; the movement comes from the mower's body. It does not rattle, chug, or belch exhaust, but instead it sings a song of sliced stems, interspersed with the rhythm of the mower’s breath. Unlike modern tractors, there is no data port for computer diagnostics. The scythe’s upkeep requires just a small hammer and anvil, perhaps a file or stone. It keeps the mower’s eyes on the ground, where any good steward’s eyes ought to be much of the time. The tractor, lawnmower, and string-trimmer are served by their users, tended to with gas, oil, electricity, and lubricants, whereas the scythe largely serves the user, in revealing patterns upon the landscape.

This all paints a very pretty picture, sure, but there might be a few folks out there snickering about relying on such an inefficient tool. It’s true that tractors are far better at compacting soil, being loud, killing snakes, and burning diesel in addition to mowing more land. A scythe in the right hands, however, can be used to tend and feed a garden or orchard, prepare paddocks for portable electric fencing, and manage for native habitat on the smaller, slower end of the spectrum. Mechanized technology, at its best, saves humans from toil and, arguably in some cases, increases the value of labor, typically at an environmental cost. But if our goal is to have more people engaged in their ecosystem, or to have the necessary collective work of stewardship and community-scale agriculture distributed and accessible, the scythe is a tool that puts its user in the right place. Namely, on the ground.

The intention of this written work is to explore how the scythe may find a modern context on the small farm, conservation planting, and homestead- perhaps your own. We will briefly cover some history of its use, lore, and social implications, offer details on how to obtain, use, maintain, and repair it, discuss the circumstances under which it is (or isn’t) superior to other mowing tools, and hopefully leave you with some direction and encouragement to pick up a scythe and use it effectively. It is possible that a scythe may not suit your needs, and my hope is that by the end of this publication, you can make an informed decision in that regard.

Those who use a scythe in the affluent Western world stand a good chance of being very foolish, very smug, or perhaps some of both. Like many lost arts and traditional practices, the subculture of scythe enthusiasts is populated by a few gatekeepers and insufferable experts. I’ll try not to be one of those. As a booster of DIY skills, I hope only to encourage you to take up the scythe, if it suits your land management needs and desires. I will do my best to refrain from saying how this tool should be used, and instead try to steer you towards practices and techniques that will keep you from feeling frustrated, breaking your tools, or hurting your body. I have about a decade of experience with this tool and can honestly say that it’s taken me about half of that time to become proficient in its use. And I continue to learn new things all the time.

The world (at least the world of the internet) can be overly full of purists and niche-skill demagogues. We all know this guy, right? Perhaps he practices a craft from a certain period, follows a very specific cultural lifestyle, or curates a particularly niche genre of artifact. Maybe he’s into traditional woodworking, or high wheel bicycles, or vintage stereo equipment, or dressing like an 18th-century dandy. Whatever it is that he’s into, he is unapproachable on the subject, and his judgments of others are very obvious. I’m using male pronouns for this archetype purposely. I’m talking about purity bros.

I am not advocating for purity in the use of the scythe. In fact, when I’m not simply being pragmatic, I’m actively being impure. On the farm, I will use a battery drill over a bit and brace. I have not eschewed zippers, velcro, or the occasional acrylic garment. In fact, I am surrounded by plastic. I generally listen to more amplified guitar music than acoustic, have no preference for the lute or recorder, and I don’t listen to any of it on vinyl. I try to balance being light on the earth with getting things done and even employ fossil fuel energy on occasion, mostly to leverage our labor in the direction of a longer game in which we can reduce or eliminate our continued reliance on fossil fuels in the future. That would mean I must transition my maintenance systems, the practices that must be revisited every year, every season, or every day, to non-fossil fuel power. An example of implementation energy versus maintenance energy: using excavating equipment one time to dig a pond for irrigation as opposed to relying on municipal water and its various ongoing energy and environmental costs. In some cases, fossil fuels are providing the leverage we need to ultimately reduce or eliminate our reliance on fossil fuels and their associated infrastructure.

I keep this in mind when I use a scythe. Grass, as long as we’re lucky, grows and grows again. If our objective is to mow grass (which it isn’t always), we must view mowing as a maintenance procedure rather than a leverage procedure. So the tools we choose to use matter because we’ll be fueling them up in perpetuity. The choice is between fossil fuels or a breakfast of oats and peanut butter. Now perhaps you’re thinking, “That’s nice, but I need to mow 5 acres; I’m not sure if I can do that with a scythe.” Well, I’m not sure either, but we’ll get there. First, we’re going to go way, way back.

Some brief historical highlights of the scythe

Mounting a blade perpendicular to a long handle to reap grass and grain seems like a fairly obvious agricultural advancement, and evidence of early scythe-like tools seems to first appear in the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture (Modern Moldova and parts of Romania and Ukraine) around 5,000 BCE. These scythes used flint inlaid blades to perform what must have been fairly grueling labor, in comparison with our “modern” blades, the production of which was perfected around the 16th century. It wasn’t until the Carolingian era (9th Century AD) that the practice of mowing and putting up hay for winter feeding became commonplace during this early era of agricultural expansion and, notably, common land rights.

The most important thing to note in terms of the scythe’s early history is that there are places where scythes and sickles rose to become prominent agricultural tools and others where the ax or machete made more sense as a means of land-clearing, and this has to do primarily with vegetation types. The traditional “scythe belt” emanated from Europe and the Middle East out to portions of central and eastern Asia, whereas the machete or ax proliferated in less open, more forested areas. Here in Northeast Missouri, we can stand to use both, and often I will carry along an ax while I’m mowing, to clear out saplings when appropriate.

In terms of crop harvest, machetes are ultimately better suited to thick-stalked plants like corn, sorghum, and sugar cane, whereas the scythe is most efficient with small grains or any vegetation that is to be cut at ground level, and the historic range of scythe-like tools reflects this. Bear this in mind for your own land management purposes, though there are some specific circumstances when a short, tough scythe blade finds a place in the woods, which we’ll cover later.

When the Ottoman Empire occupied what is now Austria during their heyday, (pun intended) they found that the combination of metallic ore, ample forests that could be cut for the production of charcoal, and swift, flowing rivers for water-wheel power provided the ideal conditions for the forging of scythe blades. Like much of scaled agricultural production, the empire required surplus grain, which in turn required a robust and often extractive manufacturing industry to produce the necessary tools. Austria soon became central to the advancement of blade production, and the forging techniques developed there quickly spread throughout Europe. To this day, Austrian blades are some of the finest available.

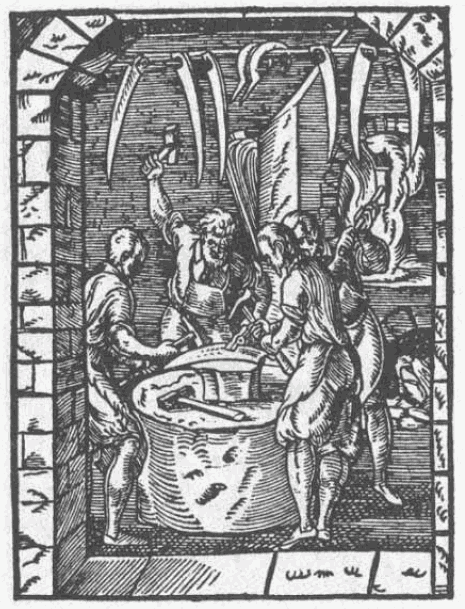

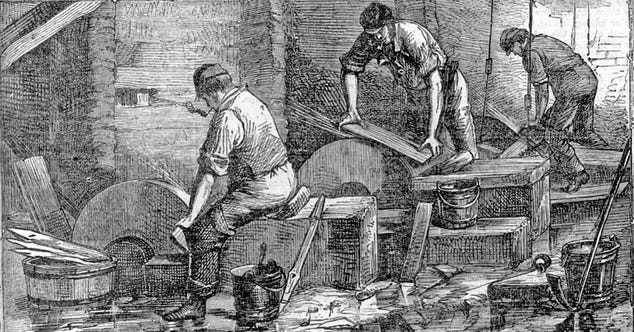

The exception to this advanced technique of scythe blade manufacture was in England, where softer steel, requiring less forging and hence less deforestation on an island with limited domestic fuel resources, was used to create blades, alongside a heavy amount of water-wheel driven grinding. This work of grinding these English blades was toilsome; workers were placed above large spinning stone wheels, the origin of the phrase “nose to the grindstone.” Unlike Austrian scythe manufacturing, which was largely rural and artisanal, English blade-makers were concentrated in urban, industrialized areas, partly as a result of enclosure. Grinding the blades became a dangerous occupation, resulting in silicosis and other complications due to the metallic air within the factories, and the Scythe Grinders Union began to take action in the mid-19th century. Frederich Engels notes the poor health condition of grinders in Sheffield, the center of English blade production, in “The Condition of The Working Class in England in 1844”, quoting a local doctor:

They usually begin their work in the fourteenth year, and if they have good constitutions, rarely notice any symptoms before the twentieth year. Then the symptoms of their peculiar disease appear. They suffer from shortness of breath at the slightest effort in going up hill or up stairs, they habitually raise the shoulders to relieve the permanent and increasing want of breath; they bend forward, and seem, in general, to feel most comfortable in the crouching position in which they work. Their complexion becomes dirty yellow, their features express anxiety, they complain of pressure on the chest. Their voices become rough and hoarse, they cough loudly, and the sound is as if air were driven through a wooden tube.

This would lead, in part, to the Sheffield Outrages, in which militant trade unionists sabotaged and bombed industrial equipment and even carried out a handful of assassinations. Eventually, some conspirators would be smuggled out of the country by the Scythe Grinder’s Union to escape prosecution.

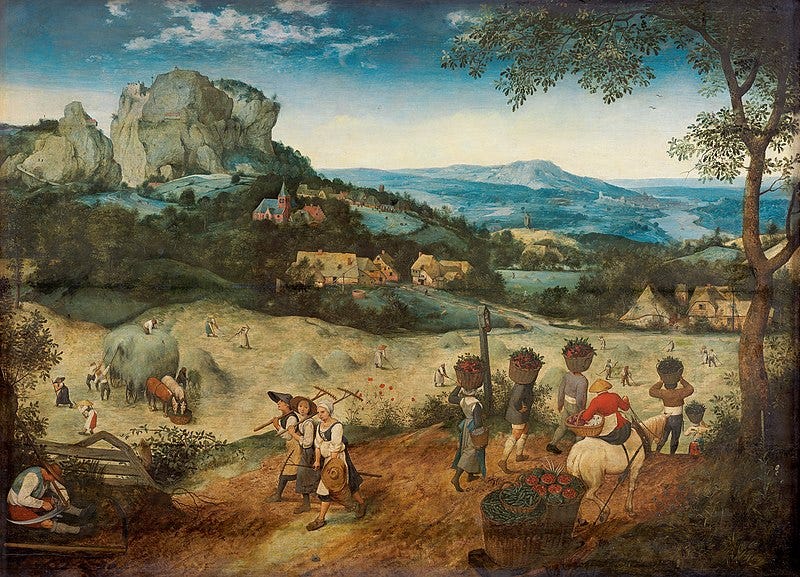

In the field, harvesting work itself reflected the labor inequality of the day. In Europe, men monopolized highly paid scything labor, justifying it with the untruth that it was far too hard of work for women to perform. I will insist that this is incorrect throughout this publication. Regardless, men typically did the mowing while women and boys performed the equally arduous, equally important role of raking and tedding the hay. While the pay was lower for women and children, it was available nonetheless, and many people could survive if not thrive on this necessary labor. The harvesting of grain, however, was a primarily female profession until the invention of the grain cradle made harvesting these crops achievable with a man and his scythe, eliminating this important income source for European peasant women who would harvest grain with a sickle and bind and arrange it for drying by hand.

Eventually, the human-powered scythe came to be gradually replaced by mechanical equipment. Horse-drawn mowers began to spring up as early as 1812, culminating with the invention of the sickle bar mower in 1833, and an industry sprang up around repairing and replacing complicated moving parts. Suddenly, the amount of land one human could impact became exponentially larger.

The scythe in our modern toolkit

Coming into the modern era, it’s important to note that the scythe is still to this day a prominent tool used for haymaking and grain harvest in subsistence cultures around the world, particularly the Transylvania region of Romania, but also parts of Africa, Central Asia, and the Middle East. Agrarian people in these regions might find access to tractors difficult, and in many cases, the care and extra resources required for draft animals and associated implements may be out of reach, or regionally inappropriate. As technology advances, tools like tractors, mowers, and chainsaws that were once easy to repair locally may even be out of reach for those of us in the affluent Western world, due to the onboard computer diagnostics and corporate control of repair work.

There are many reasons why someone might choose to take up the scythe, and economy is among them. The fuel costs for a scythe are minimal, in my case mostly oatmeal. All the repair work a scythe blade requires can be performed by the user with a hammer, anvil, file, and a couple of whetstones, and with a little experience, novice woodworkers can fashion a handle (the snath) with little more than a hatchet, drawknife, and rasp. On small plots, from the suburban forest garden to the compact homestead and even the clandestine conservation plot, the time spent working to pay for and maintain a lawnmower or “garden tractor” might be time better spent wielding the admittedly slower scythe.

Scythes look badass and displaying their proper use in your neighborhood does create a certain mystique, (hopefully not the kind of mystique that attracts law enforcement) but there are many more compelling arguments for their use than this. First, let’s look at what happens when we slow down.

A slow and steady solution

I like to think of the scythe as analogous to the bicycle. It is a tool that will get us to our destination eventually and allows us to see what so often is ignored by the speeding cab of a motorized vehicle. It allows us a nearer physical, intellectual, and dare I say, spiritual connection to the literal earth. With our feet on the ground and our eyes cast low we can observe patterns upon the landscape, noting changes in the composition of grasses and forbs of the field. We can discover the signs of wildlife, avoiding the potential to destroy habitat. We can hear the call of birds, unmuffled by the roaring, chugging clatter of machines. We can even feel variations in climate, noting where humidity lingers after sunrise. As scythe mowers, we chase the dew; unlike machine mowing, wet grass cuts the best with a scythe, and thus we spend the later hours of a morning mowing in the shadows of trees and ridges. Our contemplation of solar access to the landscape is enhanced by using this tool.

As someone who tends a small herd of dairy cows and goats, I do purchase machine-baled hay, having only put up hay with a scythe for fun thus far. And so, throughout the winter, as we feed our hay out, we usually find a few dead and baled snakes and toads. It’s unavoidable with a sickle-bar mower, but not so with a scythe. By taking time and moving at a slowed pace, I have spared the lives of countless reptiles, amphibians, and ground-nesting birds. I’ve also purposely hacked at a few rats and cottontails, but that’s beside the point, and probably not great for the condition of my blade. Mowing down undesirable weeds out in our pastures to limit their reproduction, I’ve come across other important plants in our ecosystem and purposely spared them the blade: milkweed, monarda, echinacea, a nice patch of asters, or some Joe Pye weed. I’ve been able to encourage and increase healthy and diverse populations of prairie plants on our warm-season tall grass pastures by leaving what could use a hand in re-establishment and slashing down ragweed, lespedeza, sweet clover, and other “highly successful” species. With the right blade, you can even do work like this in wooded areas, but with less agile tools like tractors or mowers, this type of stewardship is more difficult, if not downright impossible, at their high rate of speed.

Now I have not logged very much time operating tractors, I will admit, and perhaps with enough experience this might change, but mowing in a tractor, for me, takes my full mental faculties. Between the clutch and gears and multiple brake pedals, all the various knobs and levers, not to mention the smoke and sound, the time I’ve spent operating tractors has been a mostly unpleasant sensory overload, further made nerve-wracking by the knowledge that any mistake I make in its operation can lead to escalated damage due to the size and speed of the machine. While a scythe requires attention, it is conducive to contemplation, observation, and deeper thought once you’ve gotten a good handle on its use and is mowing in familiar territory.

A scythe is a tool that brings us closer to our environment instead of distancing us from it. It gives us the opportunity to learn, react, and respond to our ecosystem. It gives us a different perspective on the land we’re on and the opportunity to become an active participant in our habitat. And there are some other ways that this tool facilitates a more harmonious relationship with place that are very measurable: compaction and impact.

Compaction is straightforward… a person with a scythe will have no negative effect on the soil structure just by walking across it. A tractor, and even a riding mower, will. Soil compaction occurs at the first pass, and if soils are sodden, a lot of difficult-to-reverse damage can be done in an instant when using machinery. Compaction is a heavy issue.

When we talk about compaction and impaction, we are talking about how the blade interacts with vegetation and soil. Brush hogs, sickle bars, and most riding and push mowers have adjustable blade heights, which work relatively well on flat ground. They do not, however, respond as well to sloped or rough terrain. Even worse is how they interact with bunch grasses. Warm-season grasses, such as those native to the North American prairie, are very sensitive to low-cutting or grazing. Plant growth and lifespan can be deeply affected by cutting them too low, and the stiffened nature of mowing machinery often leads to just this scenario. The scythe mower has the advantage of being able to adjust their stance and movement to glide the blade parallel to rough terrain or lift up on their swing to avoid damaging the sensitive growing points of these plants.

While the advantages of this tool in terms of overall lightness and connection with our land are pretty clear, there are some distinct drawbacks to the scythe when it comes to scale. One way to evaluate technology is by placing it on a spectrum… on one end of the spectrum is total efficiency and on the other, resilience. An efficient tool or technology or system can have some resilience, and vice versa, but it's important to note places where these two values are exclusive of each other, to make informed decisions about the future food systems and ecology we want to promote. Like a bicycle in urban traffic, the scythe can be an efficient tool compared to its mechanically advanced and resource-intensive counterparts in some circumstances, like small or steep areas or land that requires a higher level of agility and focus to mow.

It’s also worthwhile to note that for much of the past, and even in the present day in certain locations, the scythe has been employed to manage land and get humans fed at a considerable scale. It is commonly said that the measurement of one acre is based on the area of land one person could mow in a day. In most cases, a day began early and included a meal, a nap, time to peen and hone the blade, and breaks for beer and cider, for their analgesic and motivational effects. I have found no accounts stating that the mowers were hammered in any way, and I generally do not recommend combining inebriation with swinging a razor-sharp blade on a stick for hours at a time. Personally, I can spend all day stone sober and only make it through a half acre, but our terrain is rough here and I have many distractions.

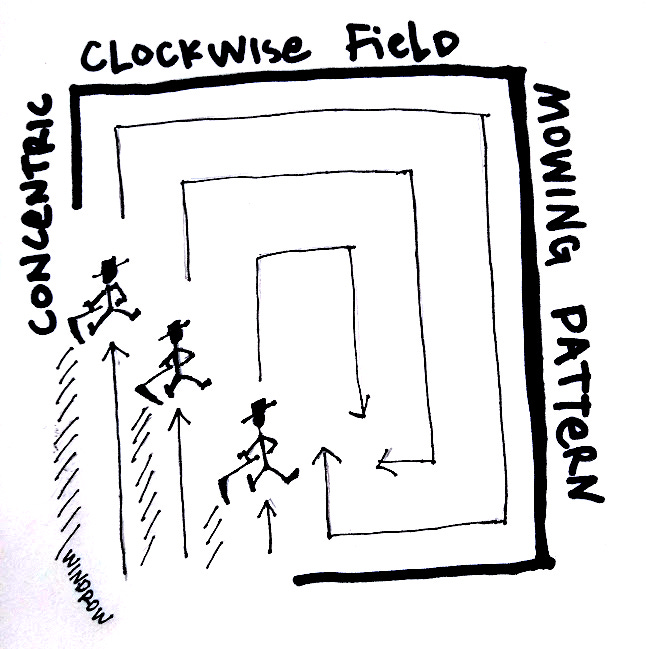

Much of the work of larger scale scything is made possible through cooperation, that skill which is so seemingly difficult for us to master in our current culture of independence. Traditionally, large hayfields were mowed by cooperative teams. On summer days beginning before dawn, when the mowers could scarcely see their blades, the team would assemble on the field edge and mow in tandem, the pace set by the most skilled among them.

Traditional haymaking assumes that all the mowers are right-handed, or can otherwise slice to the left-hand side. One left-handed mower among a group of right-handed mowers can be somewhat incongruous with the general order of the work. Whereas these people were sometimes persecuted at the height of the scythe’s popularity, there are now some quality left-handed blades available, so there’s one way in which society has advanced over time.

The mowers move clockwise around the field, from the edge to the center, in a staggered formation, cutting from right to left and depositing the freshly laid grass there at the edge of the swath.

When the field was mowed and the mowers suitably quenched and resting, the hay would then be raked into windrows by the women and children, tedded or fluffed with pitchforks, and either carted to the haymow of the barn after curing in the field or otherwise piled into conical “haycocks” that were shaped to shed rain away from the center of the pile.

It is important to note that the non-male-dominated work, that of raking, wedding, and collecting hay, was of equal value as the mowing itself. Without this careful labor, often occurring in the hottest moments of the day, the harvest could easily spoil in the field.

While it is unlikely, or even barely advisable, to harvest hay in this manner today, the principle of a clockwise (or counterclockwise with a lefty team) edge-to-center movement and a grasp of the basic importance in picking up cut grass with rakes, forks, and carts can be employed to great effect in modern land stewardship work.

Machine harvesting of hay is unlikely to be supplanted by gangs of scythe-mowing collectives anytime soon, as cool as that would be. Part of the work of this essay is to suggest situations in which the lightness, agility, and connectedness of this tool may prove to be more advantageous than any machine that costs loads of money, wastes energy, damages land and disconnects the mower from the dirt under their boots.

Applications for the Scythe

In our own project, we find the scythe useful for a handful of specific management goals, like maintaining footpaths, managing native habitat plantings, feeding our gardens and orchards, and trimming along both permanent and portable fencing. Here, I will provide some details to consider for your own land-based project.

Garden and Orchard: The work that can be accomplished with a scythe for establishing an orchard or garden begins a year before planting. We commonly use scythes to cut grass which is then raked or forked into place the summer before a spring planting. As the nutrient-rich piles of grass decompose in place, they smother sod and weeds for a pre-mulched tree planting hole. The grass must be piled high and dense, and perhaps mown and placed multiple times for the desired effect. In an open plot or field, the mower can approach the space in a similar manner as those traditional haymakers: round and round, further inward and inward, until a spiral of mown grass and forbs coils about the field, to later be raked or forked into piles. Alternatively, simple lines, perhaps two scythe sweeps across running along contour, can provide ample mulch for your plantings, less time spent mowing, and some contoured strips of mature grass and thatch to intercept and slow down water flowing downslope. We often leave these strips in place as cover for wildlife or as a place to preserve native forbs among our more human-oriented crops.

After the planting or orchard is established, ongoing maintenance of the ground cover using a scythe can continue yielding mulch for weed control and moisture retention around seedling trees. This is a way to concentrate on-site fertility to strategic points all while reducing pest and disease habitat. The flip side is that these mulch piles can harbor overwintering pests and, if made too dense, can block airflow to the plantings encouraging disease. In some instances, we’ve utilized poultry flocks in rotation over the winter to scratch apart and peck through the mulch rings. In particularly wet times of the year, the mulch can (and probably should) be pushed aside from younger trees to prevent overly sodden soil at the roots and associated fungi and disease. We want to smother competitive plants, not the trees themselves!

A method that is similar to Ruth Stout’s deep-mulch / no-dig technique for building garden beds in windrows has worked for us here as well. Affectionately nicknamed “slash and berm”, the mulch piles of scythed grass are raked into contoured bed shapes, left to decay over winter, and planted in spring or summer with peas, beans, squash, or perennial onions. In particularly dry years or areas that don’t provide as much mulch, your mileage may vary using this technique. However, scythe cuttings still make a wonderful garden amendment, much cheaper and more nutritious than straw. We take care to only use grass and weeds that haven’t gone to seed unless we’re desperate for mulch. It happens. With a thick enough layer, one can lift up the germinating mulch and carefully flip it back over now and then solarize the roots of grass and weed seedlings in the garden bed.

Some folks do a great job of digging out every tuft of grass within their garden. While I aspire to this, we admittedly have many marginal areas in our various vegetable plots that threaten us with spreading sod. Using a shorter scythe blade, or even a Japanese garden sickle (kama), we can keep these feral areas in check before they go about reseeding themselves.

The cautious and precise scythe mower, equipped with the proper blade, can even trim against garden fencing and chicken wire. While a string trimmer can also do this work, and perhaps more easily, I have often wondered where all that plastic string ends up. The correctly wielded scythe blade can even knock down thick-stemmed weeds, brambles, and the occasional tree seedling better than a weed-whacker. In our experience, mounting boards along the bottom of both sides of our garden fences create a barrier between our blades and the fence wire and also keeps creeping grasses from tangling and eventually pulling down said fence wire.

Given enough grass to mow, the potential to feed garden soils without off-site imports, in a “vegan” gardening system, increases. Here on our farm, however, we are willing and able to partner with livestock for this work, which brings us to our next scything application.

Scything on Pasture: We use scythes for a few livestock and pasture-based tasks, chief among them being the mowing of paddock lanes for moving portable electronet fencing. Anyone who has worked with this stuff understands the importance of maintaining a short-cropped pathway for preventing dewy blades of grass or weeds from shorting out the fence and potentially draining the energizer battery. This also occurs with low-to-the-ground electric fence reels, such as may be used for containing pastured pigs. I have seen everything from tractors and riding mowers to boot trampling and herbicide applications suggested as a means to keep the grass down along electrified paddocks. I won’t even go into herbicides, but machine mowing, for reasons that I’ve outlined prior, can be injurious to both the land and the grass itself, whereas trampling is arguably more labor, and many grasses and forbs will naturally right themselves gradually over time. The scythe, however, performs just fine in wet or steep conditions when machine mowing does not. And again, it offers the mower a chance to engage with the paddock composition, note forage conditions, and exclude vulnerable or valuable segments that are better left ungrazed. The skilled mower, with the aid of the even more skilled fence-setter-upper, can weave a path around seedling trees, for the purposes of precise orchard grazing, and remove potentially toxic plants from the paddock.

After the paddock has been grazed, the goats, sheep, cattle, or other livestock may have left undesirable plants to go to seed. Over time, with continued inadequate grazing, these undesirable plants may take over certain areas, depleting the overall forage value of some paddocks or otherwise creating an imbalance in species composition. Again, the scythe can help manage this issue as few other tools can. While there is some room for variance in how we manage pastures, the general idea is to trim at least some of these plants in their flowering stage, prior to seed production, when much of the plant’s energy is above ground. Gradually, you will see a difference in your pasture composition. Remember, though, that a plant that is undesirable to your livestock may still hold a key function in your landscape. I never mow all the beebalm, ironweed, or milkweed on pasture, but I do sometimes choose to reduce the seed bank and prevalence of these plants to account for the advantageous condition provided to them by our livestock. The dynamics of plant populations as they relate to grazing pressure becomes evident to the pastoralist over time, and the scythe is a tool in their toolkit for maintaining some balance in the larger working order of the ecosystem if it is tempered with observation and understanding. Wielding a scythe in a freshly grazed paddock, making a well-informed slice here and there, can make the land steward an arbiter of biodiversity, while the common practice of brush-hogging down the entire space once the livestock has left the pasture is a less nuanced, wholesale approach to management. On the efficiency/resilience spectrum, I feel that it is best practice to err on the side of resilience when it comes to paddock management.

Another worthwhile advantage of the scythe to note when it comes to raising livestock is effective soiling. Soiling may be an unfamiliar term for some. In essence, soiling is cutting fodder and bringing it to animals for various reasons. If a doe or ewe is kidding or lambing in a barn during an off-time when hay is unavailable or otherwise uninteresting, or if any ruminant animal is being isolated from the pasture for any reason, they will still need access to grass. Many folks will know that mower clippings do not fit the bill for soiling; they are torn to shreds, battered and withered, and may even have remnants of machine oil, and most of the nutrition has been literally beat out of them by the machine. A manger can be readily filled with a quick cartload of freshly scythe-mowed grass. Even pigs and poultry relish a nice armload of the stuff if they aren’t able to be directly on fresh pasture, for one reason or another. Garden cover crops like rye can even be converted to cold season silage and fed to livestock for a healthy treat.

Native Ecosystem and Habitat Management: From the rewilded suburban yard to the larger scale conservation project, the work of managing plant species by mowing down overrepresented and invasive species before seeding is important. Oftentimes, these plants begin by sprouting up a little here, a little there. And during the ground-nesting season, machine mowing can do a lot to disturb and harm the reproduction of important birds, particularly here in the tallgrass prairie. Even if actual nests are avoided, wide-scale mowing can discourage these species from setting eggs or leave them more vulnerable to predation. Herbicide is another common fix for invasives that many stewards do not find acceptable.

The scythe mower can move with the agility required to spot mow in these areas, giving under-represented native vegetation less competition. Some of the shorter blades, like gardening and bush blades, are particularly suited to this practice. I’ve found it helps to pair modern GPS technology with this simple, fixed-blade tool when performing conservation spot mowing. Most of us have a phone in our pocket. I drop a GPS pinpoint whenever I come across a patch of invasive plants on my walks and in my work until the map is populated and the time is right to do some mowing (usually at flowering and before setting seed). I can then walk from spot to spot and mow down specific patches. This quiet and undisturbing manner of vegetation management can in turn train our senses to become more aware of other trends or patterns on the land.

In some circumstances, and informed by site-specific research and information, we might look at the composition of larger areas and decide to reduce the prevalence of some native species to allow for more diversity in the field. Ironweed is one particularly successful native forb on the land here that can overwhelm many other important plants, particularly in the context of management-intensive grazing. If it appears to be detrimental to the field composition, we will scythe down some strips of it now and then. As it is a perennial, all we’re doing is setting it back and allowing other plants present in the soil seed bank to shoot their shot and gain a foothold in the mix.

Many fragile ecosystems require some amount of human intervention, particularly grasslands. These interventions can be quick-moving and potentially high-risk, like controlled burning, or they can be more subtle, like spot mowing. While swinging a scythe in your suburban setting might disturb the neighbors a tad, fire usually isn’t an option in such a situation. Moreover, the scythe mower can be very selective in how they intervene and what they leave undisturbed.

Bush scythes, which are shorter, sturdier, and less delicate, have a place both in the field and in the woods in regard to habitat management. With some experience, they can be used to cut through thicker, woody stems and saplings. While many people might use an ax or machete for this work, I find that bush scythes are more ergonomic when attempting to cut at ground level. Thorny growth that is painful to hack at with shorter blades can be easily kept at a distance from your flesh when using a scythe. As a general rule, I do not use grass blades on woody growth, and I only use the bush blade on stems no wider than my thumb. In tight areas like the woods, the shorter blade of the bush scythe can weave between obstacles with some ease for targeting honeysuckle, multi-flora rose, and garlic mustard, or to otherwise thin out over-crowded (under-burnt) areas.

How to begin

If you’ve made it this far, it may be time to learn how to find a good scythe, use it, and maintain it. A good blade may not be as cheap as you’d expect, and they do sometimes get irreparably broken, but I think it would be highly unlikely to break so many scythe blades that you could have purchased a riding mower. As of this writing, and starting from scratch, a basic kit, including sharpening gear and manufactured snath, will run in the ballpark of $300, more or less. Blades by themselves typically cost around $100 US dollars, and are usually a bit cheaper. I strongly recommend beginning with something of a modest size that’s highly sturdy. We want a blade that is relatively sharp, forgiving of abuse, and light enough to be a joy to use.

For this reason, I do not recommend using an American or English-style scythe. These are the most common blades to find here in the US, at garage sales, in the back of falling-down barns, or at the flea market. They are very heavy, tiring, and challenging for the beginner, and they can be a challenge for novice blade sharpeners to deal with. They are typically stamped out of softer steel and may require a grindstone for sharpening.

I go with Austrian, or “continental” type blades, which are manufactured by hammering, unfortunately, not by way of a water wheel. Either way, quality, hammer-peened blades are still regularly being produced in Europe, Fux being the most prominent, reliable, and funny brand name available in the US. The two sources I recommend to most folks looking to score scythe components are Scythe Supply and One Scythe Revolution. Both businesses carry the good stuff. Scythe Supply is geared towards entry-level mowers in some ways, though their actual blade offerings don’t quite match up with the wider range of blades One Scythe Revolution carries. Likely, there are other good distributors of scythes and scything-related tools, but these are the two sources I am most familiar and comfortable with recommending, as far as the US market is concerned.

Part two of this piece will be up shortly. If you’ve enjoyed it, please subscribe to

for more of Ben’s work & tune into our interview on September 24th!

A friend of mine in her 60s does not own a mower and scythes her one-acre suburban yard herself.

Scything changed my life!

We are in the tropics where grass cutters reign supreme for larger properties and machetes do the work on a smaller scale. I’m in an agroforestry context and you’ve described exactly how I started the “system” with planting saplings amongst the windrows on contour. Using a grass cutter and all the safety clothing in a “feels like” 100F humid day is utter, sheer madness.

Scything has also been very good for my mental health. Thank you for this Andy and Benjamin!