Anti-Foraging Laws: How the Rich Made Sure Only They Could Eat

American Conservation and the destruction of our Humanity

Covid was a stark reminder of the need for food to be accessible locally, and that a diversity of food sources was necessary to be prepared for unexpected hiccups in our food system. Whether a legitimate concern or not, the pandemic and Tiktok created the fertile conditions for the rebirth of a practice as old as humanity itself— foraging. Influencers brought to life the plants in our backyard and how to consume them in a way the books on people’s shelves failed to do. But to understand how we had forgotten the most basic thing that humans do, we need to understand what foraging looked like in our recent past.

Here in the United States, we can begin our narrative in the pristine egalitarian paradise of colonial New England, a bastion of free thought and solidarity across gender, race, and ethnicity. I’m kidding. That said, up to and including during the Revolutionary War, American colonists enjoyed broad foraging rights not just in the commons, but also on others’ private lands.

At least two states in the 18th century explicitly offered constitutional protections for a person’s right to enter private property for hunting and fishing, which at the time were treated the same as foraging.1 Other states offered similar protections. Foraging, oftentimes on others’ property, was an important means of ensuring colonists had an adequate food supply. Of course, that changed as industrial agriculture continued to expand. In the South, African American slaves subsisted in part by foraging on unoccupied lands, a practice that would come under systematic attack after the Civil War.

Around the American independence, American law embraced “the liberty of citizens generally to use the open countryside”, suggesting that the power to exclude wild food gatherers from private property was functionally nonexistent. Early court cases show that this was held up repeatedly. That said, foragers couldn’t do whatever they wanted. For example, although early American property laws allowed foragers to enter and forage upon unimproved lands, this right did not extend to improved lands, including cropland, vineyards, and orchards. Despite these protections, the practice slowly waned as Americans moved away from the countryside and into cities and suburbs.

Unsurprisingly, many of the laws that later came which reduced the ability for people to forage were grounded in racism, classism, colonialism, imperialism, or sometimes when they were lucky all of the above. Indigenous tribes were probably the earliest victims of anti-foraging laws put in place in North America. Shortly after English settlers landed in the New World, they began pushing Native American tribes off their traditional hunting and foraging grounds.

The colonial arrivals worked to restrict the foraging rights and practices of newly freed African American slaves. Many slaves freed after the Civil War understandably tried to leave farm work—and the farmers who had enslaved them—behind. Before the Civil War, freed slaves earned money by selling foods they foraged and hunted. In addition to income, foraging provided African Americans with some degree of self-sufficiency and self-determination.

Southern states zeroed in on practices that would allow freed slaves to be truly free by restricting access to foraging through the enactment of criminal trespass laws.2 Anti-foraging sentiment continued to foment through targeted attacks by the rich with misinformation media campaigns, using comics and news stories in the decades following the Civil War. Indigenous tribes often got caught in the crossfire against the freed slaves and also found their previous foraging practices were now illegal. For the indigenous tribes, it was not just this crossfire, but in some cases, treaties they signed with the United States government included anti-foraging language.3

When challenged on these laws and treaties, the United States Supreme Court and other federal courts historically sided with expansionist federal government efforts to limit the land rights—including, specifically, foraging rights—of Native Americans. Property laws that allowed private landowners to bar foragers continued to spread until they were, by the mid-1900s, the norm nationwide.

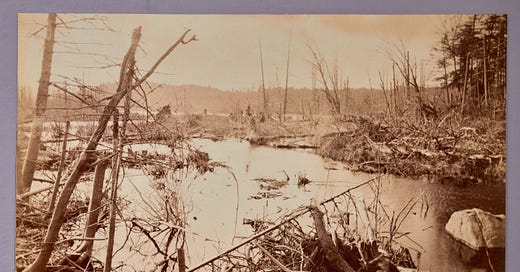

Of course, rural white farmers also felt the sting of these laws. For example, foraging for ginseng, berries, herbs, and other wild plants—along with hunting—helped form the basis of the economy and food stores of the mostly rural, white subsistence farmers living across the country. By the 1880s, New York State’s “conservation movement” began to upend the traditional practices of many foragers in the region. The push to “protect” land in this region came not from these farmers but, rather, from outside elites who sought to protect the land from its residents for their own personal gain. After massive logging decimated regions near what became the Adirondack Park, the solution of public figures and environmentalists was that no one could touch the land to protect the Erie Canal, which was vital to New York’s economy.4

This was the first drop in a series of moves that ultimately led to restricting both hunting and foraging in the region more broadly, and was codified in the creation of in the 1890s of Adirondack Park. Elitist outsiders viewed the region’s residents as primitives with “slovenly husbandry” skills who “lack[ed] the foresight and expertise necessary to be wise stewards of the natural world.”5

Our conservation laws have been framed in racism both domestically and internationally, and have underwritten genocide across the globe by forcing people off of native lands in supposed defense of the ecology.

Modern Foraging

There is no clear federal laws when it comes to foraging, and while the idea that foragiging is dictated by local conditions is a rational way to address land stewardship, this means that several agencies are involved in regulating foraging. The fun part of having various systems of local, state, and federal regulations is that many times laws are not only complicated but oftentimes contradictory. Rules can vary from park to park, from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and even year to year.

For example, a New York City Parks Department ordinance prohibits destroying, cutting, or pruning trees, or severing or removing plant vegetation. The common interpretation of the ordinance is that foraging is against the law in all New York City parks, including Central Park. The language of the ordinance is both broad and vague enough that it does not expressly prohibit picking fruit from trees or plants.

Unsurprisingly, New York City parks officials have long taken a dim view of foragers in city parks. A forager caught in New York City could face fines of up to $250. That said, the city has, in most cases, opted in favor of education and discouraging foragers over issuing fines. But there are exceptions, such as the 1986 arrest of Central Park forager Steve Brill. Brill, a New Yorker who goes by the moniker “Wildman,” was arrested in a sting operation carried out by city officials.6

Brill was arrested for leading paid foraging tours in New York City’s Central Park. Brill’s crime was described as “snatching and eating dandelion greens from the meadows of Central Park.” Can’t have people foraging those *checks notes* naturalized, non-native grasses that are not only abundant but often treated like a weed that people want to get rid of! The city’s parks commissioner at the time, Henry Stern, said he “couldn’t stomach the idea of anyone ‘eating our parks.’”

Brill’s arrest and subsequent trial was “a public relations debacle for the parks department” and made news in more than a dozen national and international newspapers. Ultimately, the city dropped the charges against Brill after he agreed to lead his foraging tours as an employee of the city’s Parks Department, which he did for several years.

Despite this, Brill’s place within the New York City government did little to soften the city’s stance against foraging. For example, in 2015, Greg Visscher, a Maryland man, was picking raspberries in a county park and was stopped by three police officers and fined $50 for “destroying/interfering with plants with: berries without a permit on park property.”7 Visscher appealed the case. A judge dismissed the case after a parks department official was unable to explain either (a) in what manner picking a berry destroys or interferes with a plant or (b) whether the permit referenced in the citation actually exists. While it’s easy to blame the city itself— New York was simply an example of what was happening across the country—an elderly Chicago man was ticketed $75 for picking dandelion greens for a salad in a city park in 2013, for example.8

Unsurprisingly, state laws pertaining to foraging vary wildly. For example, various agencies and municipalities in California make legal foraging nearly impossible, and not just this but the penalties for violating these laws can be severe. On the other side, Alaska’s so-called “Subsistence Statute,” which refers to “the noncommercial, customary and traditional uses of wild, renewable resources by a resident domiciled in a rural area of the state for direct personal or family consumption as food,” protects the rights of Alaska residents to forage in the state.

Going back to California, many of the cities themselves have super lax laws around foraging, despite state guidance. For example, in LA, if a tree grows in a public space, the fruits of it are fair game, while within county parks, the legal code explicitly prohibits picking fruit. This raises the question, how does one know if a fruit tree is in a public space that is not a county park? And that’s the point, it’s excessively confusing and designed so that they can use one of the layers of regulation against you if they don’t want you— specifically— to be foraging or in that space.

We also have a federal code that’s not *really* federal, so it’s about to get more confusing. Unsurprisingly, national parks have laws that favor conventional conservation, meaning all hands off. Despite this, Congress has pushed for a completely contradictory policy, which is to encourage the use and enjoyment of national parks and federal lands by the public.

Unsurprisingly, both of these contradictory policies are reflected in the Organic Act of 1916, which established the National Park Service, or the NPS. The mission of the NPS, housed within the Department of the Interior, is to “promote and regulate the use of the Federal areas known as national parks, monuments, and reservations . . . by such means and measures as conform to the fundamental purpose of the said parks, monuments, and reservations, which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Don’t take more than your share, right? At what exact point is the line drawn between taking and excessive taking? This thinking also leaves no space for the reciprocal nature people have always had with their local ecologies, to plant and help shape landscapes which created these spaces in the first place. So, not surprisingly, the Organic Act has been criticized for generations for its “contradictory mandate.” Any specific intent on the part of Congress to address the issue of foraging in adopting the Organic Act is unclear.

What makes this issue more challenging is that our national parks and forests are administered by two different cabinet-level agencies. In addition to the NPS, the U.S. Forest Service, which resides within the Department of Agriculture, administers National Forest units. While NPS– the National Park Service– rules typically do not require foragers to obtain a permit, a person interested in foraging within Mt. Hood National Forest, for example, would first have to read the Forest Service’s complex and detailed fee and permit schedule for “harvesting special forest products” in the park. The forest’s rules also include requirements for permitting, age, location, quantity, and other variables.

Generally speaking, the National Park Service’s default position on foraging on its lands, embodied in its regulations, is one of prohibition. The relevant NPS regulations are codified under a broad section heading, “Preservation of natural, cultural, and archeological resources.” There, they prohibit possessing, destroying, removing, digging up, or disturbing “plants or the parts or products thereof.” Additionally, they expressly forbid NPS visitors from foraging for or even possessing wild foods while in the parks. The fine for possessing, destroying, removing, or disturbing plants or plant products is $100.

Even with all of this red tape, an exception exist. Under the exception, the superintendent of each NPS unit “may designate certain fruits, berries, [or] nuts . . . which may be gathered by hand for personal use or consumption upon a written determination that the gathering or consumption will not adversely affect park wildlife, the reproductive potential of a plant species, or otherwise adversely affect park resources.” The rule also authorizes the superintendent to restrict the size, quantity, or location where these wild foods may be foraged and to limit possession and consumption to NPS grounds.

To summarize: sometimes you can forage, but the rules are based on the park service unit managing the specific spot you’re looking to go, which supersedes the state or federal conservation law, but also exists in contradiction with the Forestry department regulations over that same piece of land. The law provides significant discretion to the superintendent of each park, often resulting in adjacent parks featuring completely different foraging rules, with little or no rationale explaining the differences. These decisions are made every year, and can vary widely, from being able to pick five pounds of mushrooms a day one year and not harvesting any the next.

Despite these seemingly arbitrary regulations, the NPS can be strict when it comes to convictions. For example, in October 1991, NPS rangers in Great Smoky Mountain National Park found human footprints near an area “that had been freshly dug for ginseng.”9 The next day, a pair of rangers monitored the area and saw the defendants, Burrell and Shuler, carrying sticks of the sort that can be used to harvest ginseng. After a chase, the rangers “found forty ginseng roots sticking out of Burrell’s vest pocket.” Burrell, who faced a fine of up to $5000, claimed he had harvested the ginseng on private property outside the park. A federal court convicted Burrell, holding that regardless of whether he had harvested the ginseng outside of the boundaries of the national park, the fact he “possessed ginseng within the boundaries of the Park” was sufficient to convict him.

Fortunately, he brought this to court and it was reversed, arguing it was not illegal to merely possess a natural product regulated by the NPS within a National Park. It’s a mess. The court determined that “mere possession of a natural feature does not violate the regulation; the natural feature must be removed from the Park (physically harvested from park land), in complete defiance of at least some of the laws surrounding these spaces.

The structure of these laws and regulatory bodies gives various institutions unlimited power to decide who can and cannot forage— which brings us to today. While foraging has exploded in the past few years, the most obvious commonality across urban and rural foragers is one thing in particular: skin color. And there’s a lot to unpack about that, and how that plays into these regulations as well as the long history of unjustified use of force against marginalized groups. The takeaway here is that these structures exist to apply power— not arbitrarily— but rather when specific types of people are identified to be foraging. Whether that’s through class, race, gender or a mix of all three, ambiguity in the legality of foraging exists to perpetuate power at the whims of those with power.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 11-page chapter, of (so far) a 1005-page book with 663 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episodes #97, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Baylen J. Linnekin, Food Law Gone Wild: The Law of Foraging, 45 Fordham Urb. L.J. 995 (2018). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol45/iss4/3

Sawers, B. (2011). Property law as Labor Control in the postbellum South. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1958692

See Ute Indian Tribe v. State of Utah, 521 F. Supp. 1072, 1096 (D. Utah 1981) (“Even those Indians who had removed to the Uintah Valley Reservation in 1866 were compelled by conditions there to venture on raids into the Heber Valley in search of food needed for bare survival. Even after hostilities had largely ceased, the early farming efforts at the parsimoniously funded Uintah Agency were largely a failure, leaving the Utes to hunt and forage for food, or continue raiding on a sporadic basis.”).

https://daily.jstor.org/the-odd-history-of-the-adirondacks/

Jacoby, K. (2014). Crimes against nature: Squatters, poachers, thieves, and the hidden history of American conservation. University of California Press.

https://web.archive.org/web/20130226010355/http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/1986-04-03/news/8601200363_1_dandelions-central-park-rangers

https://reason.com/2015/08/29/maryland-man-fined-50-for-picking-berrie/

https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/elderly_man_who_picked_dandelions_for_food_gets_75_ticket

United States v. Burrell, No. 92-5223, 1993 WL 73705, at *1 (4th Cir. Mar. 17, 1993).