Rethinking Community and Ecology

Part 3 of Thriving in 2025: Climate Change, Complex Systems, and Sustainable Communities

The value of co-evolution cannot be understated. We have had five major extinctions on this planet where we lost over 90% of species, and despite this we yet have more species today than ever before.1 As species become more and more specialized and tightly related, like these co-evolved, mutualist and cooperative relationships, complex systems become extremely highly efficient. Species discovered that they were able to become more efficient and have more energy if instead of competing, they specialized. This process is called niche separation. When we speak about niche, we generally are speaking about how species find & extract their food.

Let’s consider two species going after the same food in the same ecosystem. There a few ways they can segregate their food source. The first is with micro-habitat separation; for example, chickadees & nuthatches— they eat the same exact foods in the same areas, but chickadees eat those same foods on branches and nuthatches focus on the trunk of the tree. The second is temporal separation, which is when two species eat the same foods but during different times. A really simple example is watching the growing cycle of ground plants in a forest— in the spring, various weeds and wildflowers sprout and soak up the spring sun, and as the leaves fill in, they die back for the season and a whole new crop of shade-loving plants take their place. We call these ‘spring ephemerals’ due to their short burst of color. Another example of this segregation is called resource partitioning, which is when, say two species of different sizes eat the same foods, but the larger, say, birds, eat the larger versions of the food, and the smaller bird species eats the smaller versions of the same exact food.

At the end of the day, what we are seeing is more extensive specializing. And that means their niche in the complex system is smaller and smaller, which means that the ecosystem can support more and more species, and the loss of a species is less and less significant to the survival of the entire ecosystem.

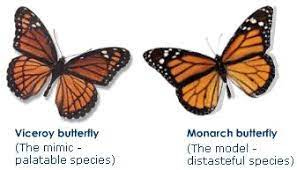

Now, co-evolution isn’t simply in regards to mutualism, cooperation, or through niche separation—we also see the use of color schemes. The first example is Batesian Mimicry— the most obvious one is when we see flies that look like bees, so that animals don’t try to eat them. It fundamentally relies on fears of the other species to be successful, which means that the mimic cannot be a large population. Another example is Mullerian mimicry, which is pretty similar to Batesian, but both species carry similar negative traits— usually bad taste. A third is Structural mimicry, when we see animals take on the shape of sticks, leaves, and other objects in their background, which is slightly different than camouflaging into your background through color, which is what’s called cryptic coloration. Now, I could go on and on, but my point is that there are a lot of color schemes that are co-evolved interactions, which creates these cooperative and mutualist symbiotic relationships, and are reflective of more dynamic complex systems.

Energy efficiency is pushing co-evolution to help make species more specialized, which makes niches shrink. Species diversity increases, which means repetition of function goes up, which means risk of loss from species loss is cut significantly and more systems are more resilient & stable. Hopefully by now, you’re seeing how this all plays together, and the interconnectedness of successful complex systems, and how these promote energy efficiency to the benefit of all species.

One of the things you might have started thinking as we’ve discussed complex systems theory is that despite this, there seem to be linear systems, and there are obviously examples of simple systems— where if you take one species out of the environment, the entire environment can struggle, and things like predatory relationships exist—why? So let’s talk about what factors impact self-organization in complex systems, and then we are going to finally bring it all home to the realm of humanity. It’s all coming together, baby.

Fostering Diversity & Self-Organization

There are a few things that can help bolster species diversity and can foster that self-organization—starting with the most obvious—variation on environment. Environments that are physically stable are able sustain more species diversity.2 That’s why the rainforest is complex, and the arctic can change drastically by the loss of a couple polar bears. Less stress from extreme environmental conditions allow animals to focus on specialization and efficiency and less on survival across multiple spectrums of conditions. A species simply doesn’t need significant adaptations, and risks of extinction from abiotic conditions are significantly reduced.

In relation to this environmental variation, the physical structure is also a significant component of fostering self-organization. Certain physical spaces limit species diversity by not providing a large enough variation to allow those complex systems to create and share a similar ecosystem. We see this with things like coral reefs, where the ecosystem for complex systems are able to thrive because of the diversity of the space.

Another challenge we see that supports self-organization is low-levels of competitive exclusion. What this means is that when a species moves in, it is incredibly adept at keeping other species out of its environment. One way to break competitive exclusion is with keystone predators-- that is, a predator that preys on specific animals extremely well. Another way to break that competitive edge is disturbance-- preferably intermediate disturbance-- enough to create space for other species, but not enough to totally decimate the environment and restricts self-organization.

While there are others, these three in particular are useful in how this self-organization can be reflected in developing human systems. When we look at the best, most dynamic complex systems, those anti-entropic systems that store energy, they typically succeed in these three areas. Again, think about the rainforest again—the reason it’s often referred to as the planet’s lungs is because it succeeds in these three categories. The climate is temperate, with dynamic varieties of landscape structure, and has massive physical structure. Additionally, one of the other categories I did not bring up is that ecological self-organization requires evolutionary time to develop those positive synergies, which the rainforest also has.

Applying Ecological Self-Organization

Why does everyone hate suburbia? Is it because it’s wasteful and inconvenient for folks that work in the city? Why, then do teenagers hate their suburban home? Well, it’s not those things, as I’m sure you know, it’s the quasi-rascist dad on his riding lawnmower crushing bud heavy and crankin’ AC/DC because you know, that was REAL rock n’ roll. Well, no. I mean, maybe, it’s probably a part of it, not gonna lie there. But, the real reason is the monotonous nature of suburban development. If we were to look at a 1100 acre subdivision; let’s say 100 acres is road, and of the remaining 1000 acres, there are 1000 houses, each with a one-acre lot. It sounds like a little slice of hell, right? Not enough to really feel connected to any type of nature with significant employment of labor in developing your own ecosystem, because you know it’s just grass, but enough to be a massive pain in the ass.

Now, imagine that same community, but those 1000 houses are densely placed together, and now you’ve got 800 acres of park space. Enough space for walking paths, forested space, and probably even a small pond. How much of a difference is that in terms of community? It’s healthier for human communities and the environment—it’s proto-cooperation. We benefit AND nature is benefiting by our conscious decision to develop our communities differently.

We can play this game out with each of these factors of self-organization. Let’s talk about competitive exclusion. In capitalism, low-levels of competitive exclusion would be a monopoly. Even capitalists understand the dangers of competitive exclusion, even if they don’t take their own advice anymore. In smaller communities, creating spaces for folks from different skills and challenges allows those same folks to develop into their full capacity and become a part of a community where they are able to contribute, instead of being drowned out by those with the loudest voices and the most purchasing power.

Providing physical stability in places like schools and within the context of having safe homes and guaranteed food and employment provides the framework for success; this is nothing new, but we are putting it into a new context that reinvigorates community development and—specifically—how collective good is good for all of us individually.

Liberalized Economies & Ecological Frameworks

Okay, that’s all good and stuff, but that’s nothing crazy, right? Well, let’s talk about the father of modern economics, the one who is misquoted possibly even more than Marx, Adam Smith. Smith, in his book Wealth of Nations, written in 1776— nearly 200 years before the Macy conference in New York—he was writing about complex systems. Keep in mind, this was pre-industrial society, and he was focused on merchant economies.

When he spoke of the invisible hand, he was talking about self-organization structured around specialized skilled individuals creating sufficient markets that benefited the whole better than the individual. By each person creating unique crafts, individuals were able to stay away from direct competition and specialize in one part of the market, which reduces energy losses. No one was, for example, a carpenter. You were a chair maker. And there was 1, maybe two chairmakers in town. And if there was more than 1, they carved out different parts of the market.

Then the industrial revolution kicked down the door and created an entirely new rulebook. Individuals were no longer craftsman who contributed to a greater good with a hand in the decision-making process in community development. Now, we focus on competition and cost cutting, and assume production will be dictated simply by abstract purchasing, which has been completely decoupled from demand— all of which hurts the worker.

Further, the bulk of capital for nearly all these different sectors runs through maybe a couple dozen multinational companies, and none of those companies specializes in any meaningful way. Unilever makes your soap, toothpaste, food products, house-cleaning products, and plenty more. You could almost live entirely off of the products of Unilever, for example. Instead of integrating with other corporations through specialized niches, they instead focus on cut-throat competition, at least on the surface which— if you recall— is the only negative/negative relationship; both parties lose.

What that means is that we’re moving away from that decentralization and even further, we’re becoming less resilient. The benefits of complex systems, which adds value to the benefit of the community, is being replaced by conglomerates which are not only siphoning out value through its linear structure from communities, but making communities more vulnerable by destroying the interconnected web of specialists that had once existed.

Further, these companies do not respond directly with the complex systems they are integrated within because the decision-making powers of these conglomerates is done outside of these nested systems. Why is insulin so expensive that people are dying? Wouldn’t the bad press be a negative for the company? Without going too deep into the economic theory around market elasticity, the basic reason is companies found it is more profitable to jack up the prices so high it would price out some users, but the return from the remaining users would be so high they would make more money selling to fewer customers.

We could go on and on about how capitalism— specifically this version that is focused on infusing capital through these massive corporations and barring entry to market for small businesses— is uniquely capable of fucking over not only our species, but the entire fucking planet. Besides, chances are, nothing here is particularly new to you, but framing the conversation within a natural context I believe adds new implication to what is happening, and helps us frame a new direction forward. What we do need to do is re-regionalize our markets and integrate these regional market systems in a way that is mutually supportive.

Before we wrap up, let’s talk about fast food. Fast food restaurants source their meat from across the globe, where it is sent to meat processing plants, where it’s measured, cooked, and frozen, only to move to distributors, then to the actual fast food restaurant. Now, Joe’s Diner that sources local food, gets their meat from a cow 10 miles down the road. So, if local makes more sense, why is fast food so cheap? Well, they can bring down labor costs by creating marginal value through assembly lines and rely on cheap forms of energy, which won’t exist indefinitely. The problem is that it is all based on huge amounts of financially cheap energy. And remember, energy cannot be created, it is finite. It, by definition, cannot be cheap. And we have talked about the fact that we need to bring energy use down, and while a fast food restaurant may be financially prudent and efficient with capital, capital is infinite and energy is not. What we have lived under is the false pretense that time is money and since time is energy, money is an efficient investment of energy. And that’s not the case.

So what do we do? Can we save our society? We’re here to talk about what happens next. What happens when shit hits the fan, and we’re building a new society out of the ashes of the old. Well, that really depends on what we’re left with. It’s this framework that reinforces the fact we cannot do this on our own as individuals, and it’s not just because we’ll get lonely, or because of the amount of knowledge in such a wide variety of subjects is insanely extensive, but because we have to model nature and our role in nature if we want to not just survive, but be prosperous. We know what we have to do to make sustainable, successful communities where individuals can value their contribution to society, and we can work to collectively create a better society within the context of the world that is left. It’s up to us to develop the tools now, while we have easy access to resources, so that when the time comes, we are as ready as we can be.

And that’s what we’re doing, we’re preparing ourselves for what comes next, and how we can be better neighbors, friends, and family.

And with that, we’ve covered global warming in a way you’ve probably never heard before. Hopefully you enjoyed it, and hopefully it wasn’t depressing but inspiring, in that we have this unique opportunity to learn from the mistakes of the planet and we can use these resources we have access to in order to make a better world in the future.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 10 page chapter, of (so far) a 31 page book with 27 sources, you can support our work a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content, the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can subscribe on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/evolution-biodiversity-ever-increasing-or-did-it-hit-ceiling#:~:text=The%20traditional%20view%20is%20that,same%2C%20with%20only%20occasional%20surges.

https://www.epa.gov/report-environment/diversity-and-biological-balance