Efraím Hernández Xolocotzi. Or, maestro Xolo. Efraím was one of those unique figures in history whose entire life was filled with events with which individually would make him worthy of any history book. His work as a collector, agroecological philosopher, educator, and political dissident all deserve respect on their own terms, but together weave a story that deserves to stand alongside ecological giants. Unfortunately, little is written in English at all about maestro Xolo, never mind his rightful place within the canon of great thinkers.

While we can’t change textbooks and academic curriculums, we can discuss some of the key moments of his life and significance. I want to preface this with the fact that this is a quick summary, and the depth of his significance and importance deserves more research, and this piece wouldn’t exist without the tireless work of Dr. Matthew Caire-Pérez and his PhD thesis “A Different Shade of Green: Efraím Hernández, Chapingo, & Mexico’s Green Revolution, 1950-1967”, which is linked in the footnotes. By a wide margin, Dr. Caire-Pérez has provided an incredible resource for the English-speaking world, and helped address the grave injustice that is the erasure of one of ethnobotany’s most significant voices.

Youth.

Born in the throes of the Mexican Revolution in 1913, Efraím Hernández Xolocotzi did not live in the town of his birth for a long time. He was born in San Bernabé Amaxac de Guerrero, a small village about 100 miles east of Mexico City, at the time one of the poorest states in the country. 1 San Bernabé Amaxac was an agricultural village. The majority of its residents were farmers. Efraím’s father, according to one person who met him, was small man with powerful hands that gave away his occupation as a “trabajador de campo” (peasant farmer). The eastern part of the town’s thin and sandy soils permitted farmers to grow only rain-fed maize. Xolo never gave the exact reasons that his family left in 1913, but his short autobiography suggests that part of the reason was religious intolerance on the part of people in his family’s hometown. For the next eight years, he lived in several places, including Mexico City and Puebla, and then to New Orleans at the age of 10, just in time for the great depression. Shortly after, he moved to New York City, and by the time he graduated high school in 1932, he earned one of the highest graduating marks in the school’s history and he left school with the plan to become an electrical engineer, although soon after starting college, he switched his studies to agronomy.

During his senior year, he took a trip back to Mexico and went to visit his father, who hadn’t come to the United States with them. No one in town knew who he was and he had very limited memories or knowledge about his father. Only 10% of rural villages like this had even telephones, so his entire contact with his father was almost non-existent.

This was a formative experience for him. While we don’t know what he expected to see upon returning home, he was amazed by how the disciplined lifestyle that his father and other campesinos practiced allowed them to overcome natural obstacles like a lack of irrigation, mountainside plots, and the vagaries of rain-fed agriculture. More important, he witnessed the conditions in which millions of rural Mexicans, particularly those in central Mexico, lived.

This is what drove his decision to switch hist studies to Agronomy; to do whatever he could to help farmers like his father. However, switching wasn’t easy.

One challenge was funding; he had to switch schools to study agronomy, and he didn’t have the money to make the switch, so he went to a state school, which at the time was less of a college and more of a secondary tech school, where he got some hands-on experience, and he later transferred his credits to Cornell. Cornell was a top agricultural school in the country at the time, and many faces he met at Cornell are involved with what we see play out years later in Mexico. Cornell was basically the place to be, their dean was Liberty Hyde Bailey, a major figure in the early 20th century agriculture community and is well-known for his work on developing systems for agriculture that pre-dated holistic agriculture, working to ‘educate’ rural America, and is responsible for bringing Gregor Mendel’s work to light.

The Portrait of a Botanist as a Young Revolutionary

Hernández, upon graduating college in 1938, told his classmates his goal was to “go to Mexico. I am going to help General Cárdenas.” General & president Cárdenas was a left-wing politician who at the time sold himself as a left-wing populist who wanted to return land to the peasant class. Understandably, the young Hernández envisioned himself uniquely suited in this endeavor. Cárdenas was president from 1932-1940 and today is still considered the most popular president of the 20th century. What made Cárdenas so unique was that he allowed his opinions to be changed based on learning new things, and advocated later in his political career for things like protecting indigenous cultures.2

Hernández immediately moved the summer after graduation with the goal of applying his education back home. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a whole lot of work for botanists at the time in Mexico, and while working at a bank, he had the opportunity to meet farmers and learn traditional practices in the region. After the bank closed, Hernández landed a position with the Office of Foreign Economic Administration (OFEA) of the U.S. Embassy during the war, since he was bilingual and had good references from Cornell.

While we traditionally think of World War 2 as being centered around the major players, the war implicated every country and who they sold their goods to. Being the backyard of the United States, the US Govt basically offered to buy anything Mexico exported since they were supporting the Allies. The added benefit was that those same goods didn’t end up with the axis powers. Hernández became an OFEA técnico (technician) helping foster the production of castor oil. To promote castor oil — used for manufacturing hydraulic fluid for jacks and brakes on war machines — Hernández traveled to study oil-bearing palms and to Mexico’s Pacific coast for other species with potential to produce similar products.

After the war, a recommendation letter was written on his behalf to Mexico’s Secretary of Agriculture and in 1945, a position opened as a germplasm collector, particularly of maize and beans, with the Mexican Agricultural Program (MAP), a program funded through the Rockefeller Foundation.

During this time, the Rockefeller Foundation helped him go back to school at Harvard, during which he refined his academic education and built the framework which would later provide him with the knowledge to defend the campesino’s from the very people the Rockefeller Foundation were trying to support with their corn research.

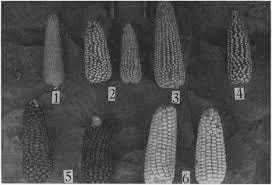

Now, obviously he wasn’t the only person that the Rockefeller was hiring to collect corn, nor was he the only one they were trying to indoctrinate into their beliefs in what the future of agriculture had to look like. He was one of hundreds recruited to do the grunt labor of documenting and collecting samples of all of the indigenous corn strains that were scattered across the country.

The Agricultural Movement in 1940’s Mexico

What was actually going on at this time that made the Rockefeller Foundation, among others, suddenly care about preserving corn genetics? At this time there were new fears about the limits of corn because of limited genetics to draw from. This drove seed companies and agricultural giants to invest in finding all of the native strains of corn, cataloguing them, and putting them into a giant storage facility which would theoretically provide the resources to deal with new diseases and pests.3 How this played out and its shortfalls are worthy of their own discussion, and I'd recommend checking out Helen Anne Curry's work on the subject in Endangered Maize. We interviewed her on the podcast in the summer of 2022, so go check that out if you’d like to hear her talk about it.

Returning to Hernández, he gets this gig collecting corn and meeting indigenous people across Mexico. He finds himself being drawn to the people and their stories and realizes that the seeds are only one part of the genetics needed to be saved— the stewardship of the plants was just as valuable. This makes his relationship a bit different than the other scientists who are hired by the Rockefeller foundation. Many go to these communities with the intent of educating them from their backwards ways by collecting old seeds and teaching them about new, better varieties, and synthetic fertilizers, while he is there to learn from them.

This research was all predicated on the Rockefeller foundation being able to point to the successes in agriculture in the 1940s in the United States. The United States was able to argue that a new world was being built on petrochemicals, and it would make food insecurity a thing of the past. Organizations like the Rockefeller foundation would bring Mexican agronomists to see the crops, and basically say, if you want that for your people, this is how to do it.

Let’s remember the context; socialist president Cárdenas who had just recently stepped down from presidency in 1940, and his successor that he supported was a moderate, with the explicit intent to highlight the need for democratic policy-making. Unfortunately, that meant liberalizing the economy, and given the benefits of World War 2 partnerships with the US, it was hard to say no, especially given the evidence provided at the time about the successes of the new agricultural models.

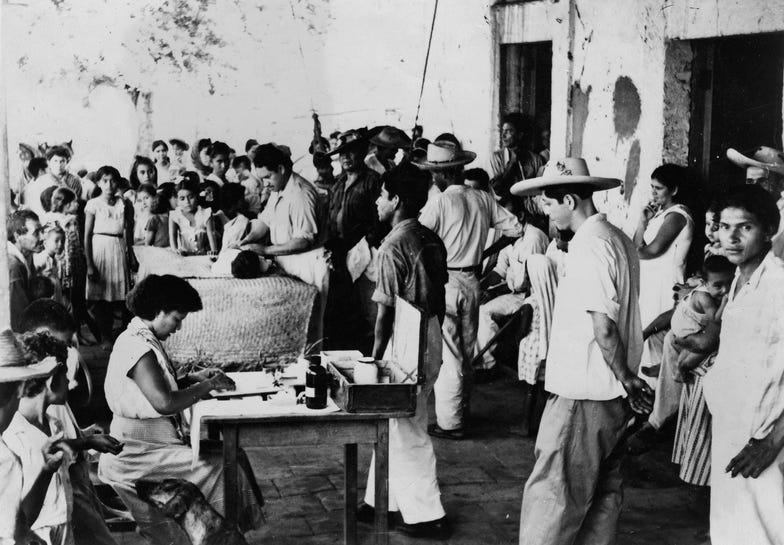

Of course, moving from campesina, small scale agriculture that relied on native crops to the behemoth of the United States agricultural system wasn’t like flipping a switch. A number of tactics, most borrowed from the United States, were applied in rural Mexico to get farmers to change their growing practices. The most commonly used of these effective methods of agronomists taking science to peasants was using an agricultural extension system based on a model from the United States.

By 1949, young Mexican men had traveled to the United States where many of them witnessed U.S.-style extension. They had seen the cooperative efforts between county extension agents and land-grant universities, saw the unimaginable surpluses produced and brought those tools home with the goal of making Mexico the agricultural envy of the world.

Salvador Sánchez, one of those who had studied U.S. agriculture and had by the early 1950s gained a position of influence in politics, was most responsible for ushering in modern extension in Mexico. Now, Sanchez is an interesting character, a botanist who absolutely fell in love with all things American, especially its science, and quickly worked his way up to being governor of the State of Mexico.

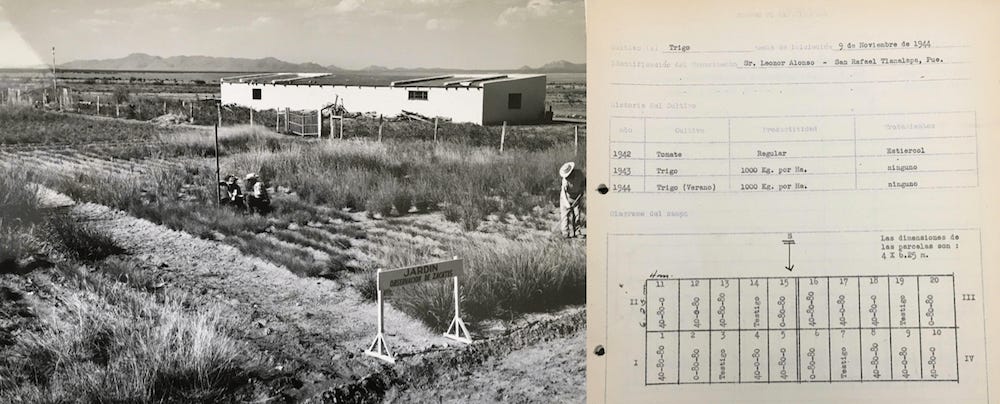

He ran his entire campaign on being the agricultural guy. He was big into restoring pasture, stopping deforestation, and collecting data. Point is, he was a typical technocrat, thinking we can simply dial-in our systems based simply on data for maximum production. And part of this was getting the extension system set up to help farmers learn how to use new plants, crops, livestock, fertilizers, and so on. The best way to sell this was through demonstration plots, almost like a world’s fair but about like, improved corn varieties and heat resistant potatoes.

In 1953 President Adolfo Ruiz and the Minister of Agriculture, Gilberto Flores, decreed a national emergency plan to increase maize and corn production. Now, I know what you might be thinking—traditional farming methods weren’t working. The real problem, though, was that manufacturing in Mexico had increased, and workers left the countryside as wage laborers.

The point here is that we see this tide changing from folks like Sanchez funded by both the Rockefeller Foundation & the Mexican government under the guise that if they do everything the way the Americans do it, they’ll live in capitalist opulence, right? And in the process, these extension schools codified the idea that local knowledge and consideration for factors of the communities in which the peasant farmers worked, such as culture and history, were of any significance.

They did all of this very, very quickly. The extension schools were modeled and put into place and then basically reformed agriculture in the span of less than 5 years, changing meat production, corn production, creating a potato industry, and working to reforest parts of the country. Sanchez was governor starting in 51, and we’re only in ‘53. Within 4 years, fertilizer use increased 5x, 2 million trees had been planted, and farmers were adopting the improved seed varieties.

Now the thing is, the Rockefeller and the giants the worked alongside with now own the seeds they’ve had folks like Hernández collect and they’re selling back new varieties that they can change through breeding thanks to those landrace varieties. The American way; steal and then sell your own creation back to you. So who are the folks investing alongside the Rockefeller Foundation? DDT Products— Yes, THAT DDT— John Deere, as well as a bunch of tractor and other agricultural equipment companies. They also funded a bunch of stuff geared at the next generation of farmers, basically stuff like the Mexican equivalent of 4-H clubs here in the United States.

Much like in Africa’s Green Revolution, the results showed improvements in production, but not at the scale it was sold. They understood that they were playing the long game, and a lot of what they were doing was trying to show young kids the ‘future of farming’, knowing they’d be more willing than their parents and grandparents to adopt new varieties and techniques. It didn’t take long for what Sanchez was doing in the state of Mexico to be carbon-copied across the country.

Fundamentally, they understood that it was all about optics. They had the extension schools, buy-in from the government, the model sites, radio programs, and even films highlighting the successes from these programs, and the constant rolling out of the latest technologies on display. It’s all about PR.

Returning to Hernández

Last I mentioned him, he got hired by the Rockefeller foundation to collect unique corn varieties, right? Yeah, and because he was English-speaking, brilliant and at the top of his class everywhere he went, and was well-connected at Cornell, he was able to get all of the best assignments for the Mexico Agricultural Program— the corn collection project. During this project, he collected 2,000 different samples of corn. At the time, it was one of the biggest collections of germoplasm in the WORLD. With this collection, along with a few colleagues, Hernández made a massive map of Mexico on the floor and placed the varieties where they were collected on the map, and they could watch the evolutionary patterns of corn across the entire country. This led to identifying 25 separate ancient races of corn and was hugely helpful in understanding the evolution of corn and how we got to where it is today. I spent about 3 hours trying to find this image again to post with the article, with no luck. If anyone finds it, please let me know so I can add it!

For Hernández, he was basically a baby among giants; his partners in this research were a geneticist from Harvard and the director of the office of special studies, which was the joint partnership between the Mexican government & the Rockefeller Foundation. Needless to say, it was this kind of thing that quickly made him a nationally recognized figure in agriculture. You could call him a niche corn star.

His star status also gave him the unique opportunity in 1946 to lead a new project into Chiapas to basically document as much plant material as possible as well as their potential use for MAP. This was the first major project by western-trained botanists in southern Mexico, one of the most diverse regions in the world. While he had valued the input campesinas in arid climates had developed, he was in awe at the incredible knowledge and what he described as the maximum potential efficiency of these soils based on an exquisite depth of knowledge. In his words,

“The disadvantage of this system of agriculture is that even under the best conditions only ten percent of the agricultural land can be planted during the year.” Deviation from this cultivation method, “in an effort to increase the area planted during the year, would result in a rapid erosion and destruction of the soils.”

So he spent his time mostly documenting the Milpa system instead of collecting seeds, even though despite this he managed to document over 500 species. Hernández saw a milpa’s efficiency in different terms from conventional measurements — the ability of its practitioners to continue its use over a long period of time and cultivation that promoted an ecological balance between anthropomorphic processes and the natural conditions without human intervention.

This was a pretty defining moment in his career; his research, while he still did what his job required, steered towards campesino knowledge. His humility and willingness to learn allowed him to learn the depth of decision-making in order to have successful harvests, from corn types and uses to religious and contextual decisions in planting one cultivar over another.

The Rockefeller Foundation recognizes during this time that Hernández is a rising star, and they give him a scholarship to go to Harvard and get his masters degree. His thesis, “Maize Granaries in Mexico,” is a study concerning the evolution of maize granaries and their importance to social cohesion among indigenous civilizations. I’ve linked it in the footnotes here.4 He graduates in 1948, and spends two more years working through the Office for Special Studies, funded through the Rockefeller Foundation, among others.

Hernández was beginning to get restless, and his natural inclination towards instigating caught him in the crosshairs of American investors. For example, when the MAP program wanted to find the right varieties of cotton to increase production in arid parts of Mexico, he suggested instead to let the native, “worthless” plants as well as some introduced, non-invasive species take over and to graze those landscapes with goats. Of course, goat isn’t as profitable as cotton for folks like the Rockefeller Foundation, who were looking to find cheaper places to grow labor-intensive crops like cotton.

During this same time, he also wrote a letter to the director of MAP, his buddy from that research project, to suggest that MAP modify its mission since, although crop production had increased, populations had increased at the same rate, and it was worth investigating the “non-agricultural effects of its wonderful achievement in agricultural technology in Mexico.” His obvious intent was to point out that despite all of the promises, the material conditions of the average citizen in Mexico was no better for all of the efforts.

A clear frustration had started to become evident in his work; he cared about helping the campesinos, but he worried about the fact that technology was working to erase their culture, practices, and ultimately their autonomy. This is one area we don’t have any real records of his opinions. He seemed to really struggle with the role of technology around agriculture, and seems inherently pessimistic at the power dynamics that exist with technology and its application.

He had been a strong supporter of the socialist revolution, which was liberalized during the time he was building his career, and he saw the programs being rolled out to fix farming in ways that don’t address the actual needs of the farmers. He saw the programs being a means to make farmers dependent on inputs, increasing productively while making less and less money, while destroying the ecosystem.

After wrestling with what he considers to be failed policies, he ultimately turns his focus away from the technological aspects and brings his primary concerns to the campesino farmers. His biggest concerns becomes how the knowledge of campesinos is disregarded by the State, while the State also continued sending people who have never farmed out to these folks to tell them what they’re doing wrong.

Now, we know this was the case because Hernández was vocal about his concerns, including during public speaking opportunities highlighting the fact that the State was ignoring their biggest asset— the campesinos. Needless to say, during this time, the Rockefeller Foundation was less interested in funding his work and supporting this very vocal dissident regarding their work. But it wasn’t easy to get rid of the biggest name in botany. In the early 1950s, he began his teaching career, and in 1953 joined the staff at Chapingo, the school where he would go on to become a major voice in the agricultural education revolution.

In part 2, we’ll explore his work at Chapingo, the student revolution, and the consequences of Hernández standing on the side of the students and campesinos.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 15 page chapter, of (so far) a 420 page book with 155 sources, you can support our work a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content (which has not been released yet), the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can subscribe on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/oso/viewentry/10.1093$002facrefore$002f9780199366439.001.0001$002facrefore-9780199366439-e-30;jsessionid=D15EDE350BDCE3694B475270F82C3A70

Curry, H. A. (2022). Endangered maize: Industrial agriculture and the crisis of extinction. University of California Press.

https://ia902809.us.archive.org/21/items/biostor-160757/biostor-160757.pdf