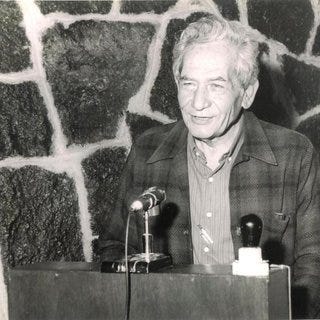

Efraim Hernandez part 2

The man who changed the course of campesino history

Mexico’s Agricultural Education

Okay so now we have to back up a little bit. We spoke earlier about Cárdenas, who was the socialist president up until 1940, right? When he stepped down, he supported a moderate successor for the sake of democracy, and that’s when we saw this liberalization of the agricultural sector as the Rockefeller Foundation swept in. So let’s talk about the colleges that the Rockefeller Foundation and later, John Deere, DDT, Ford, and others invested in.

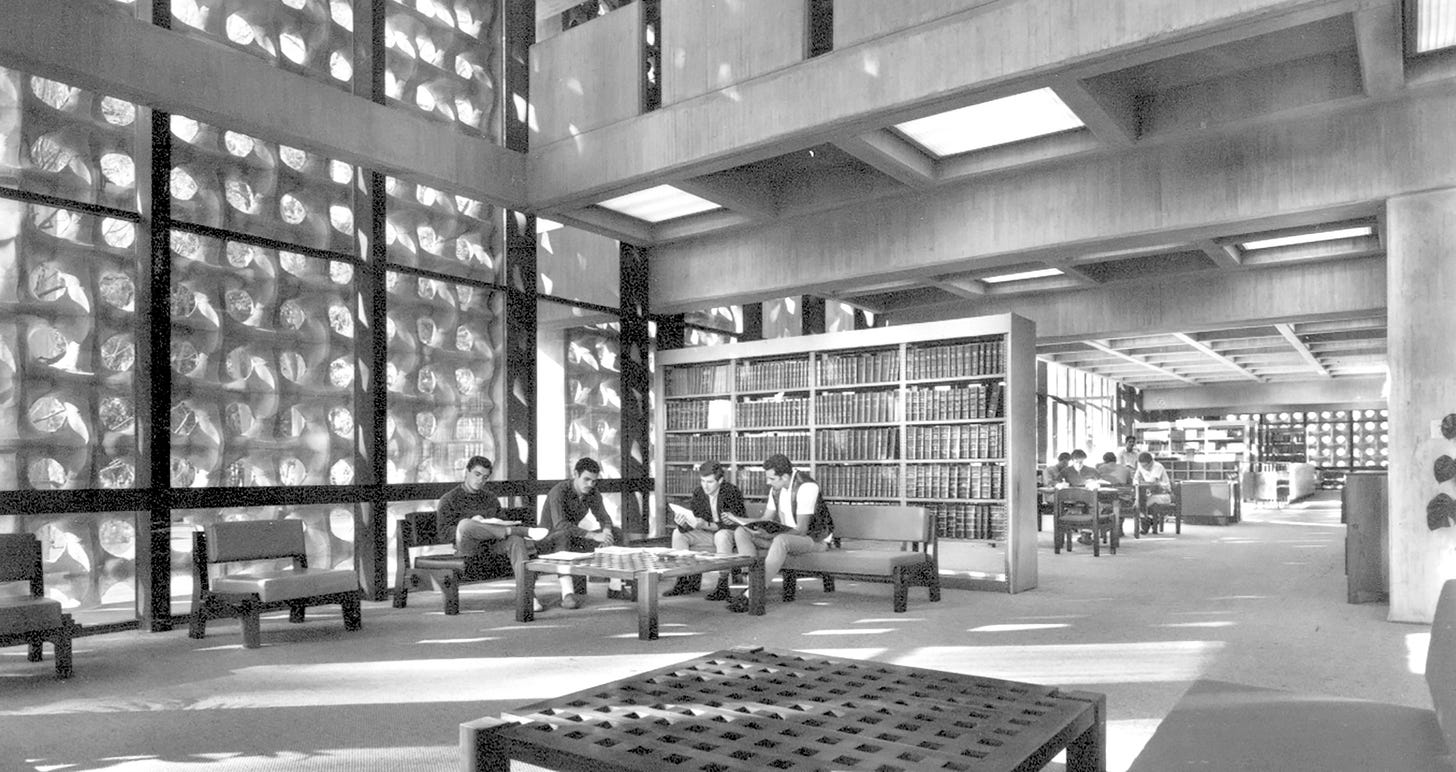

The primary agricultural college in Mexico was the National Agricultural College (the NAC) in Chapingo; it has been around since the 1850s. In 1943, at the early stages of the Green Revolution, the Rockefeller Foundation dumps so much money into it, their decisions dictate the college’s policies. We discussed earlier how the Rockefeller Foundation pushed for model farms, and these were operated as spectacles for the public. These were ultra futuristic and designed to convince people it was worth giving up their land stewardship practices for the opportunity for unmatched opulence. This was all part of the NAC; its campus basically ate up any land it deemed necessary to sell this green future.

I do want to do a bit of a history on the NAC, simply because it becomes the focal point for why Xolo proves himself not to just be a great, thoughtful botanist, but also an incredibly important tactician for the war between the campesinos and international corporations.

The Natural Agricultural College opened in 1854, as, you guessed it, an agricultural school. For the school’s first 50 or so years, it was kind of like a red-headed stepchild that got no funding, resources, or anything. And it continued that way, but during a civil war in 1913, violence in Mexico city leaked into the school as the government hunted down a rebel on school grounds and executed him in front of students on the baseball field. The students were repulsed by the violence and it left a lasting mark on the school. When the Huerta government, the one responsible for that execution, fell, the school was closed for 5 years. Many students were radicalized from this experience, and many were recruited to the Zapata cause, particularly to focus on agrarian reform in Mexico. If you’re not familiar with the Zapata cause and the Zapatistas which came decades later, it’s worth a read. The point here is that the school’s student body has an intimate history of being on the side of the campesinos.

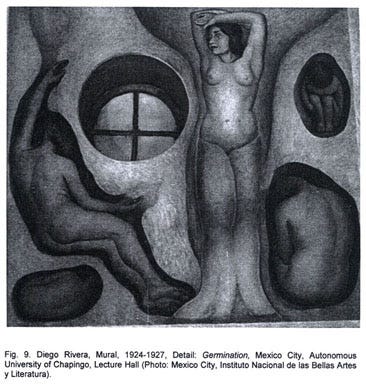

These students managed to later be collectively become hugely influential in the agriculture departments within the State, and influenced the school’s future by setting higher benchmarks for admissions, updating curriculum, and so on. It was at this time in 1924 they moved the campus to Chapingo, hence the reason people started calling it that, in order to have access to more green space. Keeping to its roots, though, outside of the campus would be an ejido cooperative that reminded students for whom they studied. Ejidos are basically common land spaces, and they were supposed to symbolize the campesinos, and that these programs were to improve their lives, not to make corporations more money.

The ejidos weren’t the only feature to remind the students who they served; they had statues of revolutionaries, massive murals and flags reflecting indigenous culture, and so on. And the government, at least at first, funded the school to be the jewel they portrayed it to be. In the 30s, however, funding slowed down, and as the facility began to deteriorate, the students went on a 4-day strike in 1937. The Minister of Agriculture under Cárdenas, the socialist president, actually wanted to send the military after the students and Cárdenas refused. Ironically, the minister of agriculture later died trying to then overthrow Cárdenas for his ‘radical policies’.

Cárdenas listened to the students’ grievances and got them the resources they asked for, and the students and faculty organized the Faculty & Student Directive Council. The students strongly believed in the mission of the school, that they were there to improve the lives of the poorest farmers in the country, and it was their job to protect it, at all costs.

In the 1920s was when it become more commonly called just Chapingo, and after decades of poor funding, the government was under pressure to invest heavily in the future of agriculture. Let’s keep in mind the various players we had discussed in the first part of this story; they all were pushing for a new Mexican agriculture as of the 1940s. Norman Borlaug, who is functionally the public face of the Green Revolution, criticized the state of the school upon his visit, stating that it was impossible to even find gas for the few tractors the school owned. In 1943 under president Camacho, the school began to receive significantly more funding as the Rockefeller Institute began investing in the school’s future.

Under President Camacho’s supervision & the Rockefeller’s finances, we see how Chapingo starts to become ground zero for the Green Revolution, and as we’ll see, the ground zero for the resistance to it.

Now, to be fair, while the school was a major improvement to where it had been 3 decades ago, it was still far from the academic rigor of most schools in first-world nations. For context, before the move in the 1920s, there was not a single faculty whose full time job was teaching. All of the textbooks were written by teachers by hand. While the school had gotten real textbooks and had some full time teachers, it still was wildly behind colleges in places like the United States. So when the Rockefeller Foundation showed up with millions of dollars to spend, basically rebuilding the school from the ground up, and replacing and updating literally every piece of equipment, it was pretty clear that there were some perks to allowing external funding.

After the Rockefeller Foundation rebuilt the school while partnering with the government, they continued on to hire over 700 people like Hernández to work in agronomy, the best and brightest in the country who otherwise wouldn’t have ever worked in agriculture in Mexico. It was a smart move, given their interest in corn genetics, as well as over the long-term as they began to lay down the infrastructure for the Green Revolution. They were basically bribing the next generation, both the future leaders and future general workers in agriculture. And with the model farms, the general population.

And to their credit, they had some successes. Many of the highest yielding crops across the country stemmed from hybrid crops from this project. There’s no doubt it had successes, and those were sold very loudly. And by 1959, because of a large endowment from the Rockefeller Foundation, the school opened the first graduate program in agronomy in the country. Everyone across Mexico, and even the leaders of agriculture in the US were touting the successes of the program. Well, everyone but at least 1 person.

Hernández taught briefly at a few other colleges before coming to Chapingo, but found the other schools were focused on industrial-scale farming, which obviously wasn’t his interest. Coming to Chapingo seemed like the proper way for a man of his stature to bury his career— he could teach at any school in the world, and he chose the middle-of-the-road state school. During his time between his expeditions and his tenure there, he had been responsible for the most important discoveries around corn’s biological history, his groundbreaking documentation on the Maya Milpa, was hired to fix the citrus black fly problem that had plagued the entire Mexican citrus industry,1 and he was responsible for moving some incredibly important species to various researchers across the globe. In a few short years, he continued on to lead groundbreaking research in grasses, and is a part of a team responsible for game-changing avocado root rot resistance in California decades later.2 His most common correspondents were the most famous botanists in the world, and many time he provided them with plants that changed the course of botanical history. By 1954, he was arguably the most important botanist in the world before he had even done much of his groundbreaking work, yet here he was taking a position at Chapingo.

When Hernández moved into academia, his unique relationship with the campesinos meant that he fundamentally understood agriculture and the role of students in their work differently than his colleagues. His comfort and collaboration with the campesinos led to his students thinking he was a bit odd since he did the opposite of what all of the other faculty did. For example, they’d be going to a site to collect samples and on a whim he’d tell the driver to take a different highway because he’d never gone that way. They’d end up going 8 hours or more out of the way, and they’d spend a night with no hotel in some random small town, eating tortillas and drinking tequila with whichever family was willing to take in a busload of nervous botany students.

Speaking Truth

The next two years at Chapingo were eye-opening. It became more clear how people were being trained. Most of his time he had been out in the field, not a part of the academic system, and had not fully understood what was happening in the classrooms at Chapingo. In 1955, only a year after joining the Chapingo faculty, he gave a speech as Vice President of the Mexican Society of Natural History, he surveyed the recent history and current status of biological studies, and he mentioned solutions. Government agencies, educational institutions, and organizations outside of Mexico, he began, had over the last two decades pushed to “improve” biological research in the country.

Consequently, these groups “established new demands and paths for our biological education.” Despite these successes, he pointed out the shortage of instructors, the lack of pay for instructors, the rigidness of instruction based on outside forces, and “In concerns to our colleges of agriculture, it is my opinion,” Hernández shared, “that the country’s needs for agronomists to be fundamentally a biologist with agricultural studies, discarding the old concept of agronomists trained to be captives in a rigid category.”

His recommendations were simple; pay instructors more, require instructors to have doctorates, do more to bring researchers internationally to Mexico, and to understand the need to recognize the unique characteristics of Mexico and work to conform agriculture to that landscape. Lastly, he recommended that the school invest in scientific philosophy requirements as well as logic.

This points to the fundamental interdisciplinary nature of something like agriculture and ecology. Agriculture is domesticated ecology and ecology is the fundamental relationship between the organic matter that comprises all life and the inorganic matter which provides the material conditions of that life. Unsurprisingly, the school didn’t care about his concerns. In meetings with the school’s leadership, he’s repeatedly quoted as saying that the problem was that there was a “U.S.-style focus on learning, research, and extension without an appreciation for the socio-economic context”.

At the Colegio, the graduate school— which was entirely funded by American interests— he was concerned that students were just regurgitating what the instructors said and weren’t engaging in new research. It was a mechanistic approach to education without the ability to contextualize any of the agronomy the students were learning and ignored and even erased Mexico’s agricultural roots. In another speech in 1956 when he roasted his audience again, he states that “[t]he strangers who address our social problems do so based on foreign assumptions and social values, and consciously or unconsciously, distort our social landscape. In doing so, they turn us into crude imitations of other places. Many of us suffer from this trauma. Our research displays this trauma. Today, our task is self-analysis, to study our own social roots until this point in time”

The same year as that speech Hernández was basically cut off from working in his area of specialization. His last position during this time with the Rockefeller foundation was studying grasses at Harvard, basically to get him as far as possible from Mexico and the currant of the Green Revolution. Funding from the Rockefeller Foundation quietly was turned off by not renewing any new contracts.

In 1960, he had the opportunity to give a speech to the biggest names in the country, folks like the head of education and the leaders of agriculture in Mexico. Despite recently being exiled, he showed no interest in backing off from his principles. In it, he railed against the destruction of Mexican identity in an attempt to recreate poor imitations of agriculture in other countries. He talked about ecological destruction, and the shortfalls of education. He elaborated on how campesinos learned botany and agriculture. He explained the value of “[o]ral transmission, elders, and adults among indigenous groups [who] constitute the mechanisms for conservation, and the accumulation and transmission of knowledge.” This process occurred over generations. Peasants gained knowledge through an empirical method that had to stand the test of time and experience. Hernández ended the speech with the most radical suggestion of all; that the leaders at the centers of Mexican education design curriculum should be based on peasants’ botanical wisdom.

The Agricultural Hangover

1960 was an important year in Mexican agriculture, and not because of Hernández’s speech. One of the major reasons is because this is when the Rockefeller foundation began to withdraw funding for these projects in Mexico while refocusing their efforts. This meant Chapingo no longer had the funding it once had, which wasn’t enough to meet the massive campus that had been built in a flurry of excitement for the future. Additionally, the negative impacts of the Green Revolution began to become evident. Again, to be fair, there were clear advancements; corn produced 30% more from 1940-1960, wheat had improved 80%, they were exporting corn and meeting their demand for the first time ever, food exports had climbed considerably, and seed banking for international sales was growing. On the surface, everything seemed to be following the dream the green revolution had promised.

In 1963 the Rockefeller Foundation began to invest in the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center as a partnership with the Mexican government. At the same time the Mexican government decided the reason small farmers weren’t adopting new methods wholesale still was because of financing, so micro-lending became a chief concern for the agricultural movement. The problem was that scaling up was too expensive, according to the government, not that campesinos had no interest in hybrids, scaling, or incorporating new technologies. The goal of the micro-financing was to make it impossible for farmers not to adopt new technologies and to take on debt; rural parts of Mexico were part of the front lines of American capitalism and the slow crawl of communism through Latin America. Forcing the supposed fruits of capitalism on poor rural farmers was as much about profiting from the need for perpetual seed and petrochemicals as it was about the Cold War. The United States didn’t care about the rural farmers, they cared about making it clear to the Mexican government that they could never find a better ally in the Soviets.

And this was just the tip of the iceberg around policies to reach the farmers who, despite the successes of the Green Revolution, hadn’t come around. Schools, radio shows, magazines, traveling extension teachers, and so on scattered the country. This was all part of President Diaz Ordaz’s plan to unify and destroy the image of poverty and ignorance which pervaded the Mexican countryside.

This project fell under the new National Agricultural Council, which worked to improve agriculture and restore the native ecosystem across Mexico. Their headquarters was in Chapingo as an entirely separate buildout for 500 students, adding to the diversity of programming that flowed through the rural area due to American funding. This collective project, called Plan Chapingo, would make Chapingo home to the various agricultural colleges already in place in the region but also it would be home to the National Institute for Agricultural Research & the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock. It would be ground zero for the future of agriculture, for the education, for the future of rural Mexican identity. But the thing was, there were problems bubbling up in Chapingo’s student body.

Despite the promises spouted by the government and the various NGOs who partnered with the State, the students were acutely aware of the fact things were changing but not necessarily getting any better. Newsletter articles highlighted this fact, and frustration transitioned to hostility. Much like Hernández pointed out seven years prior, students were trained to be agronomic factory workers, not researchers. Students were hyper-focused based on their program of study, there was no interdisciplinary work. For example, people who went to school for irrigation only studied irrigation.

We had mentioned earlier that the leadership of Chapingo were largely alumni from the school during the Huerta regime and had witnessed the execution on campus. Their solution to change the school which had felt like a joke as students was to put in place military-style rules in order to create a sense of quality, and that had continued to hold. This directed much of the student body’s relationship with the school; they believed they were not to question things, since their work was for the greater good of Mexico. But the revolutionary spirit continued to rumble beneath the surface as graduates continued to have little knowledge of farming in practice or even the ability to identify the most common plants outside of a textbook.

The student newspaper was the vector for the most loud and radical voices. They railed against poor instructors, employers complained that students weren’t prepared to enter the workforce, and the students blamed the school for poor preparation. They felt no honor in Chapingo, despite its improvements from outside investment. For example, in 1961 a film crew came to the school, and the students bullied the crew for trying to paint a good light on the school, and taunted the crew for creating content to draw urbanites to the school, decrying that “desktop agronomists were growing like a plague”. Later the same year, the governor of the state showed up for a talk and none of the students arrived on time, citing apathy.

Of course, none of this was happening in a vacuum. The 50s and early 60s was a wild time in Latin America. Guerrilla activities, the arrests of labor organizers, the US involvement in neighboring Nicaragua, as well as bubbling revolutionary activity across the region weighed on the student population eager for their chance at optimism. Chapingo’s class of 1960 had named Fidel Castro the classes’ Godfather, for example.

The point is, there’s a lot going on and the failures of the school was an easy target to direct that frustration and anxiety. Anti-American sentiment had been building up, especially given the failed actions like the Bay of Pigs only a few years earlier in 1961. This anti-American sentiment manifested in the student body relationship with the Rockefeller Foundation at Chapingo, to the point that students asked that representatives from the Rockefeller Foundation no longer give talks at the school.

In 1962, the first formal complaint came from the student body; First, they demanded that school Director Enrique Espinosa be removed from his position. Second, they wanted the Directive Council, the student-faculty group that decided on major college decisions since 1938— if you recall, part of the reform under Socialist President Cardenás— to be more involved in decision-making with all of the new growth. Finally, students demanded that college funding increase.

Espinosa resigned. The other two issues were not even given acknowledgement. The government instead decided to flex its power; the prep school, which helped high-school kids from poor communities get into the college, was closed instead. Coincidentally, however, the next day, news about the plans to make Chapingo the biggest, newest agricultural school in Latin America broke, and the student body became quietly optimistic that things would improve again.

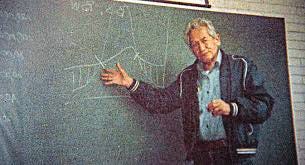

Maestro Xolo, the teacher

Where was Xolo in all of this? Efraím Hernández stood out on campus from the day he arrived in 1953, nearly a decade prior to the unravelling. Professors at the school typically wore ties, sport coats, and dress shoes. To his first class, Hernández donned a green pinned-striped suit, with a collared polo underneath, and moccasins for shoes. The pants had a noticeable hole in the rear. He wrote his name on the chalkboard, instructed students to take out a sheet of paper, and he administered a quiz the first day of class.

He wasn’t just unconventional, and his oddity didn’t retract from his rigor. He was also likely the toughest teacher on campus and not above cursing at students. Ramón Mariaca, a Hernández student during the 1980s, recalled visiting Hernández’s office to retrieve a thesis draft and finding his work in a trashcan. A scolding followed, with cursing and the admonishment that Mariaca turned in garbage posing as a thesis. For those who withstood the often-gruff personality and for those who showed effort, the relationship with Maestro Xolo was special. To these students, the xolocotzianos, Hernández gave money during financial straits, lent his car when they went into labor, attended movies, paid for meals, and shared life experiences.

In his class, debates were mandatory. Relative to other classes on campus, in which statistics or formulas yielded definitive, concrete answers, Hernández forced students to deal with abstractions and difficult questions. Erin Estrada once had an exam that asked for a definition of God. We discussed previously his love for visiting rural communities and bonding with campesinos, but additionally he had a habit of joining students in late-night drinking binges or trips to night clubs. 3

When they were actually doing the academic part of their trips, peasant growers were the greatest sources for learning, without fail. Students had to approach campesinos and ask questions. Why do you dig to that specific depth in the soil? What is the use of this plant? If you do not consume the plant or use it for forage, is the plant decorative or does it have a religious value? What other plants are grown in this region? What is the indigenous name of the plant? Any time students approached Hernández with questions about plants, he almost invariably referred them to the farmers: “Go ask them [campesino farmers]. I promise that they know more about the plant than you”

His fame and unconventional nature predicated his division from many of his colleagues when Hernández became one of the strongest advocates for major curriculum changes at Chapingo when talks for doing so began in 1962. In February, he and some colleagues began reviewing curriculum plans at universities in the United States, the Soviet Union, and other colleges in Mexico.

Technology’s main purpose, he argued, “is the application of the available basic knowledge. Consequently, education aims to give learners the information known in a field while providing for the application of this information towards a methodology for solving a practical problem, and towards facilitating time and resources to acquire the know-how for solving a problem. Research, however, involved the generation of new basic knowledge and skills. Scientific education aims to give pupils the basics… in different fields, provide a methodology and skillset for managing ideas, and teach the scientific method and science’s philosophy.” A margin, he charged, existed between technology and research, and Chapingo needed to figure out how to cultivate both técnicos and researchers. “Few people work in an area that straddles both fields. But to produce capable graduates, Chapingo needs to differentiate the two concepts and more effectively teach” students.

When the preliminary talks about Plan Chapingo began in the early 1963, he was cautiously optimistic that his membership on the Directive Council and the transformations to take place signaled an opportunity to address some concerns he had. By that summer, when the partnership for more grants from the Rockefeller Foundation came in, he made it clear that the school should be in charge of who received the scholarships, not the foundation. Unsurprisingly, this was ignored. Even more shocking, the council in charge of Project Chapingo, this massive new change to the school, attempted to reduce the student/faculty ratio of the school’s council, in an effort to take power away from the student body.

Students were suspicious of international manipulation, especially American, but the state overseers promised it was in their best interests. Unsurprisingly, Hernández continued to advocate for his biggest concerns, creating more well-rounded agrarians through interdisciplinary education.

Over the next year, roadblock after roadblock came up around funding, autonomy, resources for students, and more. Things didn’t get better. Plan Chapingo was known by the students as “Plan Ford”, a moniker given by Hernández since Ford was one of the major backers of the project. The student newspaper began writing Marxist critiques of the philanthropy of international corporations and warned other countries which were partnering with Rockefeller, Ford, and others about the lack of power they now experienced trying to grow food in their own country. Officials continued to keep students out of the loop, and the students retaliated by hosting town halls to let the general public know about the school’s wrongdoings.

As construction began, promises of autonomy between the organizations that would exist in the same space. Despite these optimistic promises of working with the student body, student feedback and surveys were never materialized, and it became pretty quickly obvious the Council had no plans to respect the needs of the students. At this same time, the council promised 10 million pesos that would be specifically for the professors at the school. Sensing that students weren’t happy, the council’s solution was to offer the students the option to pick where the new livestock building would be.

And these symbolic gestures kept happening. The prep school was reopened. Money for new things kept coming in to get students to come around to the new project, but at no point was the school in charge of any of the money. And this kept on through 1966. And that’s when things took a turn. In 1967, the Ministry of Agriculture brought the Cold War to the school in February. Ricardo Acosta, the SAG Vice Minister, began asking for the identity of writers for the leftist newsletter on campus.

An Entirely Predictable Student Rebellion

At the same time, students at “Hermanos Escobar” Agricultural College in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, were finalizing a scheme for taking over their college by force. Hermanos Escobar had similar problems as Chapingo, with the added benefit of being private but receiving tons of state money for improvements that never materialized.

Students staged what Martell, one of the organizers, later called a “revolution” on May 8, 1967. He and others arrived to campus that morning with hundreds of fliers and two hundred baseball bats. Restaging their own version of Martin Luther’s hanging of the Ninety-Five Theses, the leaders hung a notice at Hermanos Escobar’s gates indicating that the college remained closed while a meeting took place in the school’s auditorium. Students voted and agreed to support a closure and decided that the university would remain inaccessible until the federal government took over management of the institution. Those with baseball bats cleared people off campus, took control of the school’s entrance, and began patrolling on the grounds. This rebellion symbolized a fundamental change in student relations with the academia by pushing for the federalization of a private college in Mexico’s most capitalist region. And they secured control over the same institution through force.

They put everything on the line; they committed to hunger strikes, public forums, and asked other schools to shut down in solidarity for better schools. The biggest concern for the government was whether or not Chapingo would follow suit.

When news hit Chapingo, the student body debated support. Of course, administration quietly reminded the students that the government couldn’t just federalize private schools like Hermanos Escobar. It was a private school and was out of their hands.

Despite this, after numerous debates, the Chapingo student body agreed to go on strike alongside their fellow students at Hermanos Escobar under the broad framework of mistreatment by the powers that be for proper education. Once the government found this from informants, they quickly agreed to sit down for a meeting within the next week, but their efforts to quiet the situation were too late; students from Chapingo begun to hang red and black protest flags outside the school’s gates, suspended classes, and took over the campus. More importantly, this shutdown included all of the government facilities that were part of the majestic Project Chapingo.

Within forty-eight hours of Chapingo’s closure the strike also became a topic among members of the National Federation of Technical Engineers, the National Center for Democratic Students, as well as the Mexican Communist Party. “Narro” students canvassed city streets to publicize the protest via megaphones, and collect donations one day after strikers received threats about the military being unleashed on protestors.

Reports from the next couple days detailed the strike’s reach by June 20: the University of Michoacán was shut down; thirty-three rural schools in several states halted classes; hundreds of supporters took to Guanajuato’s streets to ask for donations; in Oaxaca, a state college shut down and local Ejido Bank employees began a donation campaign for the strike; and in Mexico City, fliers denounced government officials’ refusal to negotiate with students. 10,000 students were locking down colleges across the country, and protestors claimed that they expected three hundred thousand college attendees everywhere to support their cause if the military intervened in the conflict. A protest that began with baseball bats in early May had transformed into a national news item that threatened to become a massive youth movement by early mid-June.

Unsurprisingly, the government leveraged the tools at its disposal. They claimed the students had abandoned farmers across the country, that students didn’t know how good they had it, that the reports of malnutrition from hunger strikes were fictitious, and if they’d been serious they would have sat down with government officials already. And of course, they blamed permanent troublemakers, aka communists.

Immediately after their vote to join the strike, chapingueros coordinated patrol teams that guarded campus twenty-four hours a day during the school’s closure. They also designated teams to clean campus, to help with the laundry, and to take care of meal preparation. In relation to the latter task, those who refused to leave campus feasted on poultry and cattle that belonged to the college, and received provisions from sympathetic professors. For those students who detested the over-the-top military atmosphere in Chapingo, the suspension of food deliveries provided them poetic justice because they ate a prized horse that belonged to one of their drill instructors. Everyone who stayed at the school had to work, said Francisco Romahn de la Vega, “Those who did not work could not be fed. Everything fell on students.”

A handful of agronomy students succeeded in putting the brakes on agricultural education across the country. Strikers, however, did more than confirm that problems existed. They made larger indictments about how the poor educational infrastructure spelled trouble for the future because it failed to align with Mexico’s rural realities. At a rally in Ciudad Juárez on June 7, José Luis Escobedo told listeners that the strike was “the people’s fight because Chihuahua and Mexico stood to benefit” from improvement in colleges.

And that was the idea, that their message would resonate, they linked their cause to peasants. At a rally in Ciudad Juárez on June 7, Jorge Hernández took the microphone to say that he and his comrades fought for “a better education that trained agronomists to better serve campesinos.”

By linking their protest to campesinos, protest leaders disrupted political rhetoric in the 1960s. For decades, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional owned the privilege of speaking for peasants. Party officials based their legitimacy on the premise that they knew what was best for campesinos.

Given this, urban populations presumed that politician’s decades-long celebration about agricultural progress — the period that began in 1943 with the investments of the Rockefeller Foundation, when the Mexican Agricultural Program began and continued with Plan Chapingo’s inauguration in 1967 — was proof that PRI officials knew what they were doing. That image was quickly undone by the strikes. They told the public that the work celebrated by PRI leaders, as well as those in the Rockefeller Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the other institutions who advised and financed Mexico’s quarter decade of agronomic advances amounted to more smoke and mirrors and debt rather than material changes in the countryside.

Meaningful talks for ending the conflict began on June 28 when a handful of professors in Chapingo met with SAG Vice Minister Ricardo Acosta, the same person responsible for attempting to quiet the voices behind the student newspaper. Acosta met with Efraím Hernández and colleagues, and instead of gathering information or building goodwill, the Vice Minister attempted to strong arm the instructors. After some teachers offered their opinions, Acosta explained the state could not intervene in Ciudad Juárez to “Sovietize” a private college because of legal procedures.

After fielding a few comments from professors, the minister adjourned the conference by bluntly telling faculty that they should support the government, work with the available resources, and to deal with their unruly students. Needless to say, this didn’t end well. On July 1, student representatives and faculty mediation committee members discussed a plan for federalizing “Escobar.” Efraím Hernández noted in the plans that the government could take over the college, pay an indemnity to the Escobars, and form a council that oversaw the management of a new institution minus the influence of its former owners. His suggestions were the pragmatic voice for the understandably upset students.

Things worsened in the next couple of days. According to reports at a student rally on July 6, students heard about classmates from Vocational School No. 7 being “savagely beaten” by granaderos — members of the Federal District’s police force known for its excessive use of force during the 1960s — as they gathered outside the Ministry of Agriculture the night before.

Rumors flew. Stories were told of the army planning to invade Chapingo within twenty-four hours. News about the beatings outside SAG offices and the impending raid prompted about three hundred protestors to begin a march in Mexico City’s streets. The next morning, pamphlets advocating revolution from a small group calling itself the Revolutionary Leftist Student Movement circulated. Another government report from the same day indicated that more schools voted for a stoppage of activities to support “Escobar” and Chapingo and that some students spent the night of July 6 building homemade bombs.

The endgame seemed obvious to everyone — that the army would invade Chapingo. Before the worst occurred, Hernández craftily lambasted the Ministry of Agriculture’s lack of patience, suggesting that the time officials had given the committee to try to resolve things was “clearly short” and failed to give chapingueros time to deliberate over whether to return to normalcy or to wait to hear back from Chihuahua.

Hernández coyly suggested in his reports from his meetings that SAG leaders’ motivation for why their training of agronomists left the agronomists unprepared to help peasants was to ensure that the groups who helped design and finance agricultural planning in Mexico remained satisfied and that Mexico would continue need to rely on international support (Plan Chapingo received funding from the Inter-American Development Bank, a Point Four institution). Point Four, existed as Cold war funding to stop communism, basically. Hernández articulated that the institution was managed “by an authority fundamentally dedicated to other activities”, which pointed to the fact that Acosta answered to bosses in Washington, D.C.

Within the next two days, at least fifteen schools refused to hold classes and things worsened when two thousand members of an IPN counterstrike attacked “Escobar” supporters by driving a bus through a barricade in front of one of the college’s entrances.

In another incident, an informant reported that some strikers spent the afternoon bringing gasoline into a building to prepare bombs and planned to visit SAG offices the next morning. Then on July 11, at least twenty-three schools initiated a seventy-two hour shutdown during which the “Escobar” issue needed to be resolved or else more chaos would begin—alluding to the rumors of bombs. A report two days later indicated the size of the strike that the Mexican government had on its hands: a quarter of a million students around the country found themselves outside of classes in support of agricultural college attendees.

Hernández was the voice placating both sides— working dilligently with the students, keeping the government from acting irrationally, and using his platform publicly to remind the general public of the context while keeping the government honest in their portrayal. In short, he put his reputation on the line on behalf of his students. The strike ended peacefully on Saturday, July 15. Earlier that morning, strikers and the governor’s office in Chihuahua had reached a settlement. Students would immediately be transferred to the University of Chihuahua for classes over the next couple months; in 1968, the same public university would open a new agricultural college; the governor’s office would offer help with their move and financial assistance; Praxedes Giner, Chihuahua’s governor, also promised to ask the Ministry of Agriculture for funds with which to give a raise to teachers at the new institution; a student-government council would figure out how to proceed with problems at “Hermanos Escobar”; and tuition would be reduced at “Hermanos Escobar.” They basically got everything that they wanted.

Efraím Hernández’s life changed after this. Acosta did not forget the role Hernández played in making the government look like it was run by fools and doled out punishment for what he regarded as insubordination months later. In January of 1968 Hernández told an acquaintance “Per orders above me, I will probably be traveling outside of Mexico quite often during the coming months.”

Between July and January, Acosta had arranged for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center to hire Hernández to collect agricultural seeds in South America. Ironically, this was life-changing for Hernández, and was what coalesced all of his thoughts and concerns around agriculture, indigenous practices, and ecology.

The seed collection trips through the backwoods of Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru over much of 1968 gave Hernández time to develop his all-encompassing position on these subjects and he returned to Mexico as an ethnobotanist. In South America, Hernández found what agricultural investigation in Mexico had been missing for decades: the presence of people in a dynamic natural setting.

In his words, I’ll quote:

“It seems that if we start with the consideration of man and his culture[,] the relationship of man and plant never assumes its proper dimension and we soon lose ourselves in man’s belief[s], fears and fantasies so that his place in the ecosystem is never understood. We must, for this reason, start with the larger reality, the ecosystem and work down to man and plants. Viewed from this aspect, this course [i.e., ethnobotany] would review man’s role in the ecosystem and the consequences of the numerous interactions set up. A search for the biological roots of these relationships should lead to the understanding which should serve[,] in turn[,] to clarify future tendencies.”

Hernández began attending meetings with researchers interested in ethnobotany in 1972. Among the scholars at the gatherings were figures whose names would loom large in modern Mexican social sciences during the 1980s and 1990s. As Hernández bonded botany to anthropology, he also began professional and personal relationships with a handful of the people whose work would collectively reinterpret peasants’ role in Mexican and Latin American history, and it was at this time that he returned to the classroom.

These projects were part of a larger program known as “El T.A.T.,” Traditional Agricultural Technology. Studies began with intensive discussions in the classroom. Then students ventured to the field. Hernández dropped off pupils in disparate remote places where they began systematizing the agricultural knowledge of several indigenous groups. Students had to immerse themselves in the communities where they lived. This approach proved to be a success at Chapingo and the Colegio de Postgraduados. Hernández’s Ethnobotanical Methodologies seminar became a mainstay at the Colegio after 1972. Other colleges in Mexico followed suit. Ethnobotany also became a topic panel at national conferences. Once again, only five years after being blackballed by the SAG Vice Minister Acosta, Hernández had changed the future of agriculture in Mexico.

By 1977, Hernández led well-funded projects that explored the smallest details of traditional agriculture and more complicated projects related to agroecosystems. His students would go on to publish studies that detailed how peasants practiced what today is called agroecology and how they had an acute knowledge of certain plants that prevented or helped cure modern illnesses. Peasants, students discovered, had intricate ways of conserving seed biodiversity and complicated methods for overcoming environmental constraints like farming alongside a steep mountain or farming with a lack of irrigation. By the 1980s, Hernández was finally able to tell people “I no longer have to scream and yell too much to get people to understand me.”

The success of Hernández was intimately tied to the Green Revolution. Despite the fact that the short period of grain exports had disappeared by the late 70s, the country returned to importing grains and other major staple crops. Ironically, history came full circle, as Americans have begun to go south to learn about agriculture from a group of researchers who claimed peasants as their teachers.

Hernández was technically never fired from Chapingo but simply sent to do research, and upon his return with his new understanding of ethnobotany, he continued to teach and eventually became the research director of the Center for Botany at the Graduate College from 1982 to 1988. In 1988 he became professor and researcher emeritus at the Center for Botany. Towards the end of his career, he spent much of his time working on new projects, and as we stated previously, was a crucial figure in solving issues for novel crops like avocados and continued to use his platform to advocate for peasant farming across the globe.

During his life he published more than 200 articles and 6 books. The most important of these publications have been collected in a two-volume collection of 799 p. titled Xolocotzia (available at the Autonomous University of Chapingo, State of Mexico), which was published in 1985 (vol 1) and 1987 (vol 2). He died in his house on Thursday, February 21, 1991. His ashes were scattered on the college's university campus and forever left a mark on ethnobotany and changed the course of global agricultural history. NBD.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 30 page chapter, of (so far) a 450 page book with 158 sources, you can support our work a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content (which has not been released yet), the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can subscribe on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

http://manoa.hawaii.edu/ctahr/termite/aboutcontact/grace/pdfs/028.pdf

http://www.avocadosource.com/CAS_Yearbooks/CAS_45_1961/cas_1961_pg_17.pdf

http://www.ibiologia.unam.mx/jardin/gela/page4.html