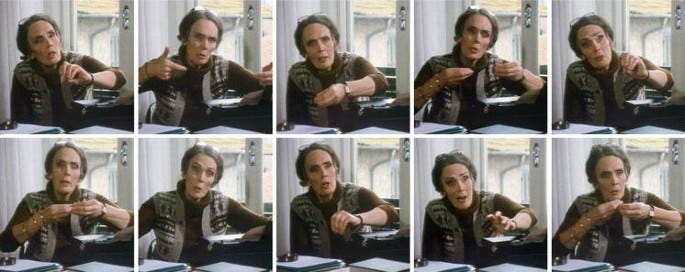

The name Erna Bennett isn’t one many recognize. A cursory internet search offers only a few suggestions of her complicated and important research; that she was involved with protecting plant genetic diversity, that she worked for the UN’s Food & Agriculture Organization– the FAO– for decades, usually without any commentary of her crucial role in mobilizing the FAO to protect genetic diversity across the globe. Her wikipedia article is only a few paragraphs long, to the detriment of so many who value her contributions to protecting biological diversity and setting a scientific basis for ecological restoration. No biographies exist, no essays or articles outlining the contributions she’s made of any significant size or rigor. The only linear history that exists of her work and challenges she faced as both an Irish woman and as a communist exists in a series of audio interviews held in storage by the National Library of Australia. For $20 and some headache, I received an interview by Gregg Borschmann as part of the Environmental awareness in Australia oral history project, where Erna has the opportunity to outline her history, how she ended up in her work, the challenges she faced and her success, and the role corporate interests played in changing the course of history. Arguably, this is the most thorough document on her history.

Erna Bennett was born in Derry in 1925 and grew up in Belfast moving there at 4; she was also the eldest of four.1 She’s described her childhood with fond memories, but described Belfast as “rather awful… I’ve thought very often since that bombing campaigns by the Germans & by the IRA have had an enormously improving effect on the city. All those dreadful buildings that I thought could never be removed have been removed, and there is every possibility that it could become a very very beautiful city.” (1:45)2 If you can’t tell, she wasn’t afraid of controversy, and we see that play out throughout her history. It became obvious early on during school; her first scientific paper was on the subject of controversy in science. Upon her planned baptism by the local church, she argued with the priest about the story of creation until he kindly left and never returned to do her baptism. Her willingness to engage with controversy stemmed from her father, who advocated the importance of ideas being able to withstand criticism.

World War 2

Her father, a policeman, was a socialist, and Bennett remembered how the events of the Spanish Civil War enraged him.3 She discusses in the interview with Gregg Borschmann how her father’s friends in the International Brigade during the war were tracked by a map in the living room with little flags, and her father’s frustration of the slow march of fascism into Madrid left a permanent mark on her childhood. As an influx of antifascists and Jewish people moved into Belfast as war became inevitable, Erna enlisted, despite being a year too young to do so. At first, she worked in the kitchens, doling out soup to other recruits. Frustrated by the lack of seriousness given to her dedication, she repeatedly applied for transfers, lying about her qualifications (she once wrote that she could fly a plane. In her words, she could it was “just theoretical”). Despite being the only woman, she managed to get into the aviation training program, the first and only woman in the class at the time. The instructors weren’t happy about it; she described the first day when all of the students took their first flights. All of the students did one small flight around the city and landed, while her flight was extensive with precipitous drops and loops so that by the time she landed she felt sick. When she got off the plane, her instructor grinned at her, extending his arm, and she ignored him, refusing to acknowledge the terror he had conspired to put her through.

After completing her training, she was put on ferry duties, repositioning equipment and staying out of the main action, until they needed her due to her fluency in Greek. She worked for the British intelligence service in the Middle east and Greece, during which time she was first exposed to Lenin, despite already self-identifying as a socialist, she found his words better explained her lived experiences than other leftist writers she had read. Her work with the British intelligence was to identify which Greek activists were more sympathetic to British causes and work to elevate them within the Greek activists.

She ultimately defected from the British allied forced and joined the Greek Partisans, who were arguably far more radical and anti-fascist than the British army.4 Part of this was the fact that she saw the British planning the future government in Grecian cities with the Nazis to keep the Greek radicals out of power after the Nazis left. This period of her life influenced her politics for the rest of her life, and she was associated with the British, Italian, & Australian communist parties for most of the rest of her life. While this period was hugely influential for her understanding of politics, it was also influential on her understanding of ecology and agriculture. She had spent her time in Greece in a rural environment which was able to highlight the richness of traditional agriculture. She also was able to see how important landraces were losing their significance on the landscape.

Her abandonment of the British army did not go unnoticed, however, resulting in her being charged with desertion in the face of the enemy and court-martialed. She said that it was probably her father's standing in the police force that resulted in her being sent back to England rather than sentenced to death. When she came back to England in 1947 she tried to get back to Greece without any luck, and even tried to pursue journalism to create an excuse to return to Greece and cover the Greek civil war unfolding. When that failed, she decided to use the time to study at London University & then Durham University for botany. She graduated in 1953 and struggled to find work in research.5 A major piece of this was Bennett’s association with the Communist party, as the red scare was building up as the Cold War directed national conversation. She’s said that this time was so difficult for her that even her friends wanted nothing to do with her because of her communist affiliation. She worked as a waitress for a number of years, surviving paycheck to paycheck and shunned by her classmates and friends.

Scotland

After a few years, she was able to find a job at the National Library for Science & Technology because of her linguistic background, and the position was at an incredibly low rate because of her background. She worked in this role, quite below her qualifications, for a number of years. A few years later received an opportunity to finally apply her knowledge at the Scottish Plant Breeding Station, again at well-below the pay she should have qualified for. She worked with Jim Gregor, who was the director at the time and had become well known for his work on micro-evolution. It was at this time she started formulating her ideas around genecology, a branch of ecology which studies genetic variation of species and communities compared to their population distribution in a particular environment. What that basically means is that we can study the relationship between genetic variation and environmental gradients within a species. For example, if plants grow differently because of an environmental change, for example— the jack pines of the Pine Barrens versus the jack pines of a oak-hickory forest which grow very differently because of soil types— does that environmental factor impact its genetics, and if show— how?

Now, there were folks exploring this area of study, but Jim Gregor as well as Erna began to explore this area of genecology with far more rigor, and were able to provide data behind the adaptive process for plants and what selection pressure and environmental factors were able to do. The results showed plants evolved far quicker than we had previously thought to new environments. What we’re talking about really is what we now know as plasticity within plants and how it influences the genetics of its descendants, and Erna’s work focused specifically on domesticated crops. If we take genetic diversity and bring it into a domesticated condition, it won’t represent the same way it did before being given this new environment. It was in her work at this time that she began to understand and the concept of genetic diversity as a meaningful resource and she coined the expression “genetic conservation”.6

While genecological studies with cultivated plants was being done before her work, the Russian plant scientist Nikolai Vavilov had been working on such studies for years. In fact, his research, along with Evgeniya Sinskaya, were translated by Gregor and were hugely influential to Bennett’s work. In 1964 & 1965, Bennett wrote two papers which put her on the radar of the FAO; Historical perspectives in genecology. In: Record of the Scottish Plant Breeding Station, Pentlandfield, Roslin, Midlothian and Plant introduction and genetic conservation: genecological aspects of an urgent world problem. In: Record of the Scottish Plant Breeding Station, Pentlandfield, Roslin, Midlothian.

The FAO

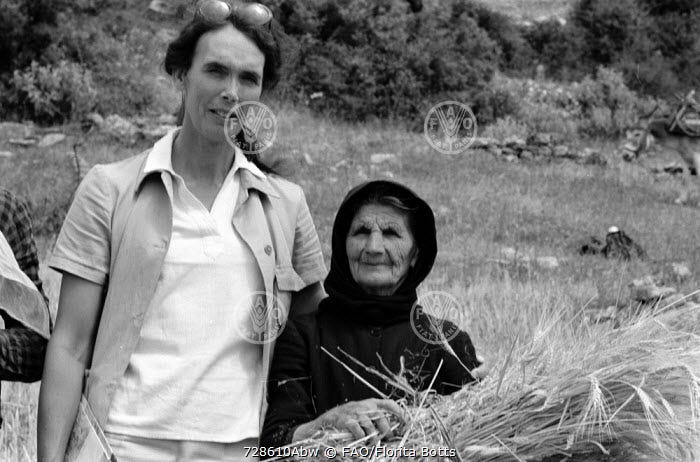

Two years later, Bennett joined the FAO and she continued her field work of collecting plant genetic resources. Her newfound position with FAO gave her wide access to pursue her passions around protecting plant diversity, coordinating national & international activities across the Mediterranean and through central Asia. Her time in Turkey in particular was important for her understanding of how quickly the impact of uniform, ‘improved’ crops was destroying local diversity. Not only was it destroying local diversity as a whole, it was destroying the very resource that was being used to keep those same improved crops from destruction from disease and pests, since it was these various landrace varieties which provided the genetic code to make those monocrops more resistant to issues.

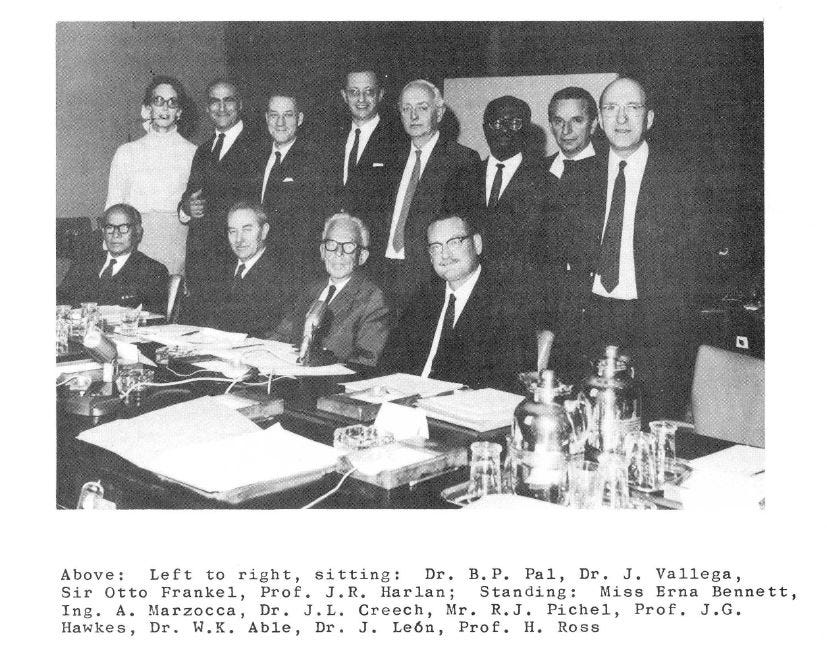

This is where she was able to utilize her platform to explore the significance of genetic diversity and its conversation; she went on to be a huge voice in the FAO Technical Conference of 1967; it was here that the term “genetic erosion” was coined.

She later called the conference a “watershed moment” for the defense of genetic diversity, and that despite their concern, they were not fully aware of the severity of the crisis on a global scale.

“The future challenge is therefore to manage agricultural ecosystems in a manner that will (1) avoid the buildup of substances that are either directly hazardous to human health or damaging to the structure and functioning of ecosystems; (2) ensure the effective recycling of essential plant nutrients; and (3) preserve wherever possible, both species diversity and spatial heterogeneity in the agricultural landscape. This challenge is a time when it is frequently suggested that the best hope for increasing the world's food supply lies in the future intensification of agriculture, particularly through the diffusion of modern agricultural practices to less intensively managed parts of the biosphere.”7

She went on to say that … “‘erosion’ of our biological resources may gravely affect future generations which will, rightly, blame ours for lack of responsibility & foresight. But at this very moment we are equally deprived, because many, one might say most, of these genetic resources are not available for general utilizations by plant breeders, agronomists, foresters, horticulturalists all over the world”.

While this was a watershed moment for plant diversity, it’s important to put this within context, a few years prior to her joining the FAO, they had a similar conference focused on ‘plant introduction’. This plant introduction, unsurprisingly, was framed along the lines of the Green Revolutions that had been taking place in latin America, Africa, and Asia, and was focused on how to integrate conventional ‘European-style’ crops into these new climates. This meant they weren’t concerned with invasive species or general plant introductions as an ethical practice, but rather how to maximize production of wheat, barley, maize, and timber production based on northern hemisphere species. The focus was on how to get them to succeed, while also not really considering the aspects of genecology which folks like Erna and her colleagues were identifying as critical parts of how plants would interact with novel landscapes and ecosystems. Erna, in her interview, suggests that the sudden concern with work like hers a few years later was because the proponents of the Green Revolution were quickly seeing how this practice of transplanting crops was creating genetic erosion and these projects were not showing the results they had expected.

Her argument was that when we breed for resistance to disease, for example, we breed with the assumption of all or nothing. This meant we put strong selection pressure on our plants to identify one particular genes to stop that disease, as opposed to a number of diverse plants which may, through their genetic diversity, develop a number of different partial measures for reducing the severity of that disease on it, and the disease or pathogen only had to find a new way into the plant.

In her words:

“One could breed a crop resistant to this or that disease. And then, within a year or 2 of the crops commercials use, you could find that the resistance would get broken and you’d have to start again… do we contend ourselves with this major gene breeding which dodges for a few generations, for a few years, the impact of a disease, but then presents us with the problem with breeding further resistance when that breaks down. Or, should we perhaps look for something different, which might be called ‘adaptive’ resistance.. in which you never have compete resistance, because it’s based on an evolutionary co-adaptation between parasite and host which allows the host to continue growing reasonably well and allows the pathogen to establish itself… without causing devastation. In other words, to recreate… the conditions that apply in traditional farming and primitive farming… where you never see a crop wiped out but you never see a crop without some disease.”

Her goals were geared towards advocating and protecting genetic diversity with the understanding that it was this same genetic diversity which best protected future ecology. After this conference, she wrote a paper outlining the severity of genetic loss and its direct connection to the Green Revolution, which she submitted to the FAO, only for it to never be seen again. In an interview, she says she believes that it was likely because of lobbyist pressure, since her findings would have been detrimental to the continued growth of the Green Revolution.

In 1970 she had a number of papers published, and the term “plant genetic resources” was used for the first time to an international audience, which drove what was later called the “plant genetic resources movement”.8 This movement was predicated on a fundamental understanding of how genetic adaptation worked. Her argument, along with other genecologists, was that adaptation to a new environment could not be attributed to specific, singular genes, but the the action of many genes at once. The significance of this was that the plans for crop improvement would best be achieved through a combination of many genes, not by focusing on just one or a few. What this meant was that genotypes needed to be saved, not just single genes that show a specific trait.

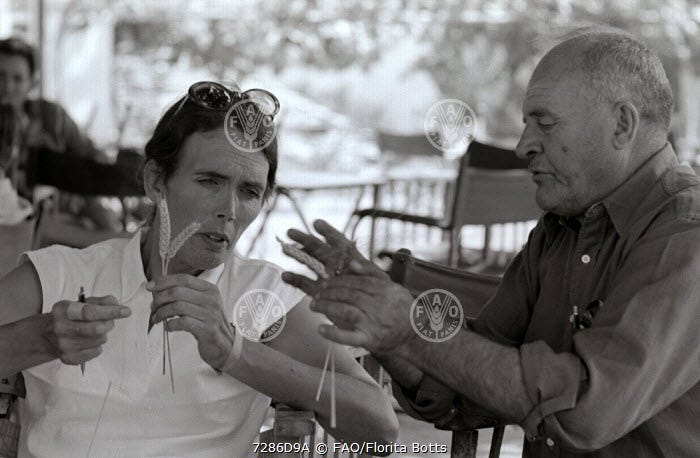

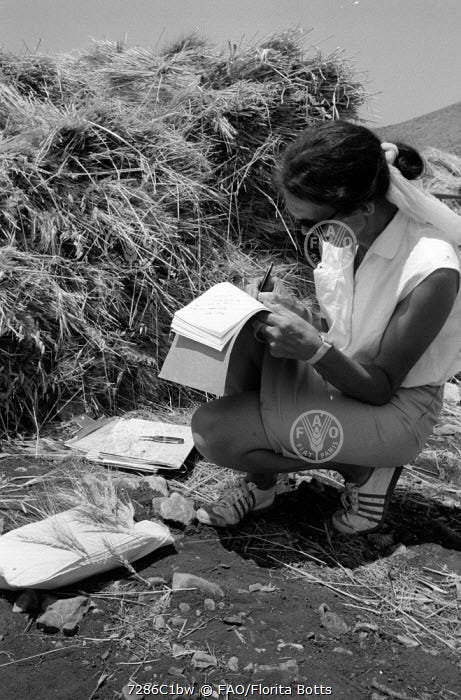

Bennett suggested methods which would be accompanied by surveys of climate, local variations, agricultural practices, social structure, customs, and history. Much like Efraím Hernandéz, she understood the significance of local knowledge and how plant evolution was situated within a community and its particular, ancestral knowledge. Without detailed, local knowledge of habitat variations, there would be no reliable basis for plant exploration. During her time with the FAO, she had repeatedly been involved with collecting samples and found that the traditional sampling strategies of identifying plants for specific traits without content was unsuccessful.

Much like Efraím, her work wasn’t always fully understood at its time. Otto Frankel, one of the world’s most renowned geneticists of the time, disagreed with Bennett— not in principle, but in practicality. “What is the purpose of keeping landraces in a ‘dynamic state’ in their original site, if the site itself is changing beyond recognition?” he asked. Further, “As in all scientific endeavour, she has to have a good idea, and test an intelligent hypothesis, but genecological studies should not be regarded as necessarily a routine thing”. It was at this time, that Bennett later recalled that she had begun to regret the fact that crop adaptation was no longer taking place in the farmer’s field but rather the breeder’s plot. This was in stark contrast to Frankel, who in fact worried that the genetic diversity being exposed to the changing agricultural practices would lose what the genetics had been preserved for. It should be no surprise then that Frankel was an avid supporter of the Green Revolution, believing that Bennett’s plan would never do more than feed local communities, while his goal was to feed the world.

Bennett had no qualms defending her position. At the 1967 conference, she laid out her concerns with how the Green Revolution through orgs like the Rockefeller Foundation were storing seeds. She articulated that:

“I see no special advantage in conservation in the form of seed apart from the eminent one of convenience, and I think that attempts to find other merits in the ‘steady state’ which seed storage represents, seem to come dangerously near to adopting museum concepts. The purpose of conservation is not to capture the present moment of evolutionary time, in which there is no special virtue, but to conserve material so that it will continue to evolve. Such ‘continued evolution’ could only be possible in in situ collections.” [my emphasis]

My point isn’t that Frankel was particularly wrong or motivated by the wrong things, but rather to highlight how Bennett, an Irish woman and newcomer to genetics, fundamentally grappled with the issues facing biodiversity loss differently than her colleagues, at great risk to her own career, as we will see.

Despite their disagreements, Erna co-authored and edited the first classic book on genetic resources with Sir Otto Frankel. Published in 1970, “Genetic Resources in Plants”, their book was key for initiating the 1972 Stockholm Conference on The Human Environment (a predecessor of the 1992 Earth Summit) to call for the conservation of crop genetic resources.9 It was also at this time she met her future life partner, Pru Rigby.

While storage facilities isolated from the place of the seed origin ultimately won the battle, and continue to exist, all of the shortfalls Erna identified came true; we discussed this at points in both our history of corn article & the series on Efraím Hernandéz, but the full extent of the challenges experienced in centralized seed storage is explored in depth in Helen Anne Curry’s Endangered Maize, which focuses on the seed collections of maize in Central America.10

What started to become clear to Bennett, who was already suspicious of the goals of the Green Revolution, was that centralizing seeds and storing them like a “museum”, as she had described, was the best solution for corporate use, not necessarily for communities or farmers themselves. This became most obvious when it came to what collection practices were; collections could either be targeted at general collection of materials for the sake of diversity or collections were focused on specific plants. Missions under the FAO, in contrast to the collecting work under Vavilov, were instead focused on specific plants with high value instead of working to protect genetic erosion across a diversity of species in what Vavilov called “centers of diversity”.

These seed banks faced a number of shortfalls, from being directed by corporate interests to poor documentation and classification to many seeds simply not being stored properly and going bad. Many sites were severely understaffed and simply weren’t capable of even keeping track of what seeds were stored in the first place. Further, as documented in an interview, Erna noted that she had spoken with individuals who freely admitted that they were given explicit permission by their employers to try and buy seed collections to store in their own personal bank. Effectively, corporations were using the publicly sourced seed banks for personal discretion and to remove those seeds from the public bank. The pressures weren’t just from the purchasers but even people in the FAO who advocated for meeting with these purchasers. These same FAO managers would push Erna to tamp down her criticisms of corporations or the donor countries.

Back in the field, Erna continued to do her intensive collections work across Italy, southwest Asia, Greece, and Afghanistan.1112 As time went on, she was more vocal in her concerns about genetic storage, and more importantly, by powerful private— corporate— interests. Her concerns weren’t just about the seed companies but the petrochemical companies and their interests to develop plants that were resistant to specific chemical applications.

For example, CGIAR, an organization we discussed at length in the development of A Green Revolution in Africa, became intimately involved with seed collection and seed storage specifically in Africa in the 70s. This French organization was largely funded by the US Government, various European countries, OPEC, among others, and quickly opened 15 international research centers to lead their research. In this process, they effectively outsourced FAO’s work and cut Erna and her team out of the research and storage practices. In creating these layers of non-profit organizations, it was much easier to direct seeds and funding between companies and governments, and together there was an illusion of diversity of players supporting and finding successes in the Green Revolution, which drove further subsidies to bring petrochemicals and improved seeds into Africa without criticism.

Blacklisted

During this time, she was directed to explicitly not contact any researchers and to not connect with any other staff or attend any meetings without explicit approval from her new boss. Erna described this time of her time with FAO: “I sat around doing nothing getting paid for it. I protested, I insisted, I stomped and hystericked, I fought, I scrabbled, both with him, my division director, and the agricultural department director… I was totally encapsulated in a barrier that deprived me of all work.”

With nothing to do, she ran for the FAO staff counsel and won, and went on to become the president of the staff counsel. For 3 years during the early 70s this was her main focus; she led a strike for worker protections and wages and also set up a joint action committee which oversaw approval of any public release from the director’s journal. With this new power, suddenly the FAO were willing to give Erna anything she wanted to get her to step aside. At this same time, her public recognition continued to grow and she joined the editorial board of the FAO Plant Introduction Newsletter and Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter, which allowed her to write a number of editorials and use the newsletters as a pulpit of a sort.

She was able to maintain the ability to restrict the PR of the FAO through her role as the president of the staff council in regards to the Green Revolution for 2 years, before she was no longer capable of maintaining the role. Erna had recommended Trevor Williams to lead the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) as one of her last leverages of power with this position, one which would turn out to be a mistake. The IBPGR was a “conservation resource” for CGIAR, an organization which was accountable to no one but shareholders, while FAO was at least accountable to the U.N. The new director, Trevor Williams, caved quickly to corporate interests, and accelerated the increasing corporatism within IBPGR & FAO.

Frustrated once again by the corporatist interests of the institutions around her, Erna had an opportunity to leave in a blaze glory when a complaint about monocropped timber trees from the Forestry Department of Germany was accidentally handed off to her to be responded to by the FAO. She drafted up a response, fully criticizing the influence of corporate interests in certain projects and resources used by the FAO, which was rubberstamped by the directors of FAO without reading, immediately causing an uproar about FAO documentation highlighting the influence of corporations on their decision-making. In her interview we sourced from, she acknowledges that she has kept a copy of this letter in her files, but we are unable to find a copy of this letter anywhere to draw specifics from, unfortunately.

Needless to say, FAO, CGIAR, the countries who funded them and the corporations who were invested in these nonprofits were less than thrilled with the very public criticism coming from FAOs own desks, especially from one of the faces of FAO (Not Erna, but whomever rubber stamped her letter). The FAO demanded that Erna re-drafted her letter, defending the investments and directives of the corporations behind the organization, at which point decided her time at FAO had run its course, penning a letter about how she refused to rescind her position, after two decades in 1981. Quietly, FAO asked her for terms of resignation, which allowed her to retire at 55. She later found out that her boss had instructed their HR department to “get rid of Bennett at any cost”.

Retirement

Her first day of retirement was a special one— May first of 1981. She spent the day joining the May Day March in Rome, untethered to any corporate interests. Her retirement, of course, wasn’t an actual retirement. She returned to her work she started in her youth as a journalist writing about specific concerns like corporations claiming genetics as intellectual property and dedicated her time to the NGOs she felt were doing the important work of actual genetic conservation.13 She began writing heavily, incorporating her ecological positions with her politics, taking a leading role in the Australian Marxist Quarterly journal as a board member, and pushing for coordinated action against the capitalist destruction of the ecology, stating that “[i]f there is no other way to save a resource from destruction, they must break the law.”

Interestingly enough, after she left FAO, CIA representatives had reached out to offer her an opportunity to shill for CGIAR, which they wanted to replace FAO, since CGIAR would operate explicitly outside of the grips of the public. In response, Erna wrote a series of articles defending FAO and explaining why FAO didn’t live up to its potential, but that it could be far more successful than CGIAR. Her point wasn’t that the FAO was inherently bad, but it inevitably was guided by corporate interests because of the influence and money corporations had. CGIAR had, in contrast, very few redeeming qualities, in her opinion.

The following years turned out to be transformative for FAO. Funding began getting cut by corporate investors (possibly in part because of her work and her vocal resistance), and more internal people began criticizing how close the organization was to corporations. Even CGIAR faced similar issues at the time, and the organization reached out to Erna, looking for support and guidance on new Board Members to appease a wider audience to shore up funding. Internal staff who stayed in touch with Erna informed her of how different the organization was being managed since her departure, and that had she stayed on for a few more years, she would have very much be at home. The question that remains is whether or not her very public departure was the impetus for this change.

During the following decades, Erna’s relationship with FAO warmed, and she was even invited to speak at their conferences. In her 1994 interview, she painted an optimistic picture of the future, feeling redeemed by the failures of the Green Revolution and the need to find an alternative— an alternative she had been advocating for thirty years.

During the 1980s she moved to Australia due to her partner, Pru Rigby’s, personal health issues and her family’s personal issues. In Australia she continued to focus on her writing & focused on intermingling her politics with her ecological concerns, bridging a gap in conventional Marxist literature. In a 1994 Australian Marxist Review quarterly, she articulated that:

“Tree-hugging is now just as much a part of the class struggle as is the struggle in defense of the dispossessed and landless poor whose retreat into the forests has sometimes been, in the past, among the first causes of forest degradation — for it needs to be remembered that behind the sophisticated causes of our present global disasters lies capitalism’s greatest crime — poverty in a world of plenty, and brazen wealth in a world of poverty.”

In late 1994 moved one last time to Scotland, where her career began. Erna never slowed down, however, and in 2001 was invited to a conference in Spoleto, Italy to finalize the International Undertaking on Plant Genetic Resources to defend farmers rights in an era where the subject of seeds as intellectual property had become the central focus. She described the experience as “disturbing… The first inter-governmental meeting I had attended in at least a decade and a half, this was a blood-chilling déja vu, marked by the same legal play with words concealing savage obstructionism, and the same arrogant determination to satisfy the same private corporate interests that had crept through the gaping cracks of our defective defense of the public interest in the 1970s. The meeting produced a toothless, truncated document, scattered with beautiful words.”

Despite these damning words, she ends her last written op-ed with the following:

The day is coming when scientists and intellectuals will accept the need to take social action and accept social responsibility as an integral, and not a supplementary part of their scientific responsibility, adding their voice and their actions to those of millions of others. That will be a day of great hope for a direly threatened world.

She died in January of 2012 at her home in Scotland with her partner by her side. Her work has been largely buried, and what little exists hides per politics.

We’ve uploaded her 4 hour interview to our youtube channel in 4 parts as unlisted, you can find the 4 parts here:

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 30 page chapter, of (so far) a 480 page book with 171 sources, you can support our work a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content (which has not been released yet), the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can subscribe on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

http://www.geneconserve.pro.br/site/pags/biography3.php?id=17

Borschmann, G. (1994, November 21). Erna Bennett interviewed by Gregg Borschmann in the Environmental awareness in Australia oral history project. The Australia Oral History Project. other. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/513784.

https://www.smh.com.au/national/pioneer-of-plant-genetics-20120325-1vsom.html

Jackson PM (2012) Erna Bennett obituary. The Guardian, 8 February 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/theguardian/2012/ feb/08/erna-bennett-obituary

Hanelt, P., Knüpffer, H., & Hammer, K. (2012). Erna Bennett (5 August 1925–3 January 2012). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 59(6), 967–970. doi:10.1007/s10722-012-9872-0

Bennett E (1964b) Historical perspectives in genecology. In: Record of the Scottish Plant Breeding Station, Pentlandfield, Roslin, Midlothian, pp 49–115

Frankel OH, Agble W, Harlan JB, Bennett E (1969) Genetic dangers in the green revolution. Ceres, FAO. 2(5): 35–37 [reprinted 1970 as: The Green Revolution, Genetic Backlash. Ecologist 1(4):20–22].

Pistorius R (1997) Scientists, plants and politics—a history of the plant genetic resources movement. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome

https://grahamstevenson.me.uk/2011/08/25/bennett-erna/

Curry, H. A. (2022). Endangered maize: Industrial agriculture and the crisis of extinction. University of California Press.

Bennett E (1970) Genecology, genetic resources and plant breeding. Genet Agrar 24(3):210–220

Bennett E (1971) The origin and importance of agroecotypes in South West Asia. In: Davis PH, Harper PC, Hedge IC (eds) Plant life in South West Asia. Edinburgh Botanical Society, Edinburgh, pp 219–234

https://grain.org/e/289