If the oak tree is the tree that fed the world, Hickories are the tree that helped humans thrive in North America. Across eastern North America until only 300 or so years ago, hickories were the staple crop consumed most commonly. Like the oaks, their mast years drove the successes of communities, and even until recently, there were records of thin-shelled hickories that were likely planted and protected by indigenous people. To eat a hickory nut is to taste thousands of years of history on the continent.

For the uninitiated, hickory nuts are a treat; they can mostly similarly be compared to pecans, which is unsurprising given that they are so closely related they can interbreed (and hicans are an area of breeding worth exploring for several reasons). Hickories, specifically from shagbark hickories, have a subtle, maple flavor which underscores the pecan-esque flavor. The hard part is getting to the nut itself. While we call hickories and pecans nuts, they are referred to as drupes or drupaceous nuts rather than true botanical nuts because they grow within an outer husk. The scientific term, tryma, is how these unique types of fruits are classified. This can seem confusing at first, but if we consider the husk as an inedible fruit and the nuts the pit, they’re much easier to understand and categorize.

The hickory appeared on the North American landscape at some point between 35 and 60 million years ago, making it one of the later arrivals to the continent after splitting from the walnut.1 Unlike the story of the oak, hickories weathered the last ice age in much better shape, reducing the number of genetic divisions from the isolation that we saw with oaks. All of the hickories on the east coast of North America today are the remnants of a band of trees that survived from the Carolinas to the east of Texas.2 The impact of forcing the entire species to exist in a small land space has meant that the genetic diversity in hickories is fairly low, except for hickories from Texas. What’s particularly interesting is that the pollen record from before the last glaciation event suggests that the communities in which hickories existed were unlike anything today; there are no modern analogs for most of the species they existed in the community with. Further, despite the vast geographic diversity of the southeast, the genetics of the hickory show little diversity, mostly likely due to its role as a generalist species in many types of forest ecosystems.

Now despite the fact the genetics of hickory are surprisingly uninteresting, we do have some interesting data coming from ploidy studies.

Ploidy is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively, in each homologous chromosome pair, in which chromosomes naturally exist. The significance of this is that polyploidy variations tend to exhibit stronger growth patterns, and we are only at the beginning of fully understanding how ploidy can impact fruit size and growth.3 hickories are considered diploid, which is common in many plants. However, specifically in North America, there appear to be some tetraploid species, meaning they carry four sets of chromosomes.

Needless to say, this discovery is significant, and worth thinking about as people begin considering breeding projects. Further, if we look at the species that are tetraploid, they’re largely southern hickories with smaller nuts. The interesting thing is that their oil content seems to be quite similar based on their ploidyness, and raises questions about the role of domestication in their development. Researchers have long believed that polyploidy has played a role in which plants become domesticated, because of all of the benefits they offer when trying to create ‘unnatural’ selections. However, at this point, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence backing this ‘logical’ perception of how ploidyness would play into breeding choices. That said, research to this point has focused on ‘conventional’ annual crops and little research has focused on perennial crops, which have a much longer timeline of breeding work to create viable crops that would qualify as domesticated.4

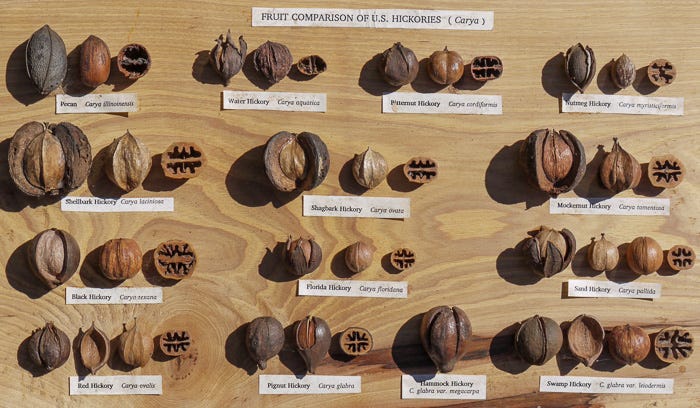

The graphic above is interesting because all of the tetraploid species share a similar geographic region, and further, overlap with longer-settled regions by indigenous groups. One nut in particular that is worth noting is Carya pallida— Sand Hickory— which, while one of the smaller hickories, has a very thin shell and very sweet meat. While traditionally considered a southern species, it is capable of surviving up to zone 5 and thrives in poorer soils. However, there’s conflicting opinions on whether or not the sand hickory is actually a thinner shell, with conflicting reports, suggesting that there may be a subset of sand hickories with thinner shells— or simply that there has been poor documentation of the sand hickory.5

What also makes the Sand Hickory an interesting tree to consider for breeding work is that much like the Ozark Chinquapin that had disjunct populations in Delaware, Sand Hickory also has had disjunct populations in Delaware, suggesting that it may have also been a tree that was collected and valued by indigenous communities.6 There are also reports of disjunct populations in southern Indiana, which was also a major region of plant breeding work by indigenous people.

A Brief History

The hickory’s name stems from pawcohiccora, an Algonquian word for a soup made from hickory nuts as they were described by John Smith upon meeting the Powhatans.7 Records show that hickories have been used as a food crop and as an oil crop for at least 8,500 years.8 Much has been written about the hickory, an interesting novelty to colonists in the New World. For example, Pehr Kalm reported on these nuts, which he referred to as unique walnuts as such:

Nuts of the hickory with the shaggy bark are about the size of a large nutmeg. When both the outer husk and the very hard shell surrounding the kernel are removed, the meat is very sweet and delicious. The nuts of the hickory with the smooth bark are a little smaller, about the size of an average nutmeg. The shell around them is very thin. They also have a fair size kernel which tastes rather bitter when fresh. When they have been lying for some time, however, the bitterness disappears, and they taste good [my emphasis]. In the autumn nuts of both types are collected in sufficient quantities and kept until needed.9

While the first hickory described above is clearly shagbark, the second, however, is likely pignut or butternut hickory, the two hickories known for bitterness and typically not eaten. While pignut has been documented around many indigenous communities, most research has pointed to the oil as the primary reason for its popularity. Kalm continues in his report, explaining how the hickories were consumed:

“Old Swedes living in New Jersey related that, during their childhood when the Indians lived among them in large numbers, they made a good sweet milk from these nuts in this manner: They collected large quantities of nuts, some hickory, and some black walnuts. The nuts were pounded to pieces, the kernels removed, and ground into flour which was mixed with water. The mixture looked like milk and was just as sweet and agreeable in taste.”

The scale of which hickories were processed cannot be understated, either. Despite the introduction of corn as a staple crop, hickories were a major piece of indigenous diets. Willian Bartram describes in the late 18th century what he witnessed in the southeastern United States, explaining that:

“I have seen above an [sic] hundred bushels of these nuts belonging to one family. They pound them to pieces, and then cast them into boiling water, which, after passing through fine strainers, preserves the most oily part of the liquid.”10

Now, unlike acorns, this process is consistent regardless of geographic region. This makes sense given that hickories have much less geographically-based genetic variability in comparison to oaks. Evidence from various experiments seems to suggest that the more dry the nuts are before processing, the easier the nutmeats pull away from the shells. Further, the finer the nuts are pulverized, the more complete the separation of the shell from the nutmeat.

Generally speaking, there have historically been two products that have come from this process— nutmilks and oils.11 If your interest is in the nutmeat, the powder of the nutmeats can be dropped into boiling water and stirred— almost all of the shell fragments sink to the bottom while the pieces of nutmeat float to the top and can be skimmed off. The resulting nutmeat ‘powder’ can be used immediately or spread and dried for storage.

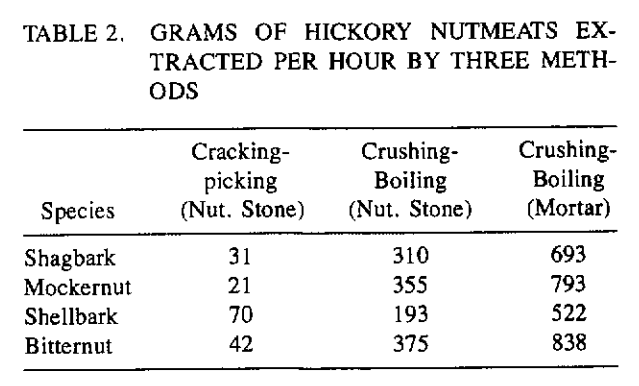

If your interest is oil, boiling the same product longer will cause much of the oily portion of the nutmeats to separate out and rise to the surface where it can be skimmed off. It’s estimated that for every 100 pounds of hickory nuts, one gallon of oil can be produced.12 Even after skimming, the ‘milk’ that remains can be used for soup stock or drank, once the sunken shells have been removed. The caloric return per hour by turning the nutmeat to powder and boiling versus attempting to pick out each nut separately is significant.

If we recall from the Oaks piece, the largest, easiest-to-process burr oaks could produce 3972 calories an hour in processing. Focusing on Mockernut, since they’re better flavoring than butternut, at 657 calories per 100 grams gives us 5210 calories per manual labor hour, a 31% increase in calories per hour!13 Even the lowest-caloric nut, the shellbark, is only a few hundred calories below the burr oak, which was by orders of magnitude more productive calorically compared to other acorns. In short, the caloric return on hickories through this process is orders of magnitude above most oaks and this should point to its significance as a potential staple crop, and why many sites seem to show that hickory consistently has the most ubiquitous remains out of nut crops across the east coast, even suggesting that hickories continued to remain as significant calorically to corn through the 18th century.14

While this has overwhelmingly been the primary method for processing hickories, another variation documented among the Cherokee of eastern Oklahoma involved creating “nut balls” known as ku-nu-che. This process involved drying nuts out for months to ensure the nut separates more easily from the shell, and then is cracked carefully. The larger pieces of nutshell are removed before pounding the rest into an oily meal that can be shaped into a ball between 2.5 & 3.5 inches. If stored in cool, dry environments, these balls can be stored for years.15 The ball can then be added to hot water, where it melts into a milky concoction that is strained and served over hominy or rice. The balls make transport of food easier than containers filled with milk.

Unsurprisingly, storage for a staple crop such as this was just as important as processing. In the oaks piece, we discussed the pits that were dug for acorns and hickories in modern Georgia, and this wasn’t a solitary example. Numerous sites have shown dozens and in some cases hundreds of storage pits, cooking pits, and evidence of slow heat being applied to dry nuts before storage, which would allow them to store for years, helping offset the time between mast years.16 The average size of these pits was three feet wide and three feet deep with a bell shape, the narrow point being at the top to reduce the exposure to surface air. The bottoms of the pits were burned to harden the base and lower sidewalls. For more information on these pits, check out our piece on oaks here.

The Hickory Landscape & Climate Change

Historically, hickories have diversified extensively, thriving in the sandy barrens of the southeast to the lowlands of Appalachia. Recent research suggests that even the hickories used to moist conditions are far more resilient to drought conditions than previously believed, making them prime candidates for climate change resilient restoration.17 While drought has slowed growth in hickories in eastern forests, they were impacted by late-season drought less than white oaks.18 This same study suggested that further drought conditions may increase the importance of hickory in the future to absorb the roles white oaks play in many forests across the East Coast. Not only is the issue of species change a concern because of drought, but also due to mesophication.

Now, mesophication is in itself a newer concept, but one which is so logical, that it’s surprising it was only in 2008 that the term was coined.19 The term explains the evolution of fire-adapted ecosystems to long periods of no fire. The paper itself (cited above) discusses the historical role of fire across the eastern United States and how those fires were managed. Now, the term mesophication attempts to encapsulate the shifts in biota and microclimates that influence the species composition within these forests— and unsurprisingly, rapidly changing landscapes (on a larger scale of human management) have significantly impacted biodiversity.

In one particular study, researchers found that forests undergoing mesophication were seeing accelerated deaths of young oak and hickory trees— roughly 125 years old on average.20 Shade-tolerant, fire-sensitive species were instead beginning to take over the forests, and younger oaks and hickories were not filling in the understory. These forests that have been stable for thousands of years have quickly begun to be replaced with more mesic beach-maple forests. Without fire and thinning, the forests were creating conditions that were not ideal for particularly red oaks, although white, black, and chestnut oaks struggled as well. Pignut showed some of the most resilience in these conditions, again reinforcing the need for us to consider the role of hickories in these forests as necessary species for ecosystem survival. But is the hickory able to carry the weight of the oak on its shoulders?

Before we can try to answer that (first, no we can’t answer it), it’s worth exploring this subject in a bit more detail. While hickory seems to do better in drought conditions than oak, and it seems to handle mesophication as well as and usually better than oak, specific research on drought seasonality is significant and highlights the importance of hickory in the future. A group of researchers focuses specifically on how the seasonality of drought conditions influenced how these forests were being changed from oak-hickory to beech-maple, and an interesting nuance was discovered; while hickory survives late-season drought better than oak, they both survive late-season drought better than sugar maple, a dominant tree that often outcompetes oaks and hickories in mesophic conditions.21 Therefore, the timing of drought conditions will play an important role in forest productivity and carbon sequestration as forest species composition changes and could have a substantial impact on how tree growth responds to future climatic change.

In recent studies focused on the East Coast, the Carya genus has been consistently documented as the third most important species for ecological services, behind oak and pine, and in some plots, ranking the most important.22 While there’s no simple replacement for the oak, nor should there be, it’s an important reminder that the biodiversity of the forests can manifest in several different ways, and the hickory offers an important role in keeping our forest ecologies resilient. Between its historical role as a staple crop for indigenous people, its role as an ecologically significant plant in the eastern forests, or its potential to survive our increasingly destabilized climate, there’s no doubt more focus needs to be put on finding the hickory’s place in our future.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 13-page chapter, of (so far) a 758 page book with 396 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this episode, #186, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Coder, Kim. “Native Hickories of Georgia I: History & Genetic Relationships” Publication WSFNR-23-24A. August, 2023. https://bugwoodcloud.org/resource/files/27844.pdf

Bemmels, J. B., & Dick, C. W. (2017). Genomic Evidence of a Widespread Southern Distribution during the Last Glacial Maximum for Two Eastern North American Hickory Species. https://doi.org/10.1101/205716

Gilbert, N. (2011). Ecologists find genomic clues to invasive and endangered plants. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/news.2011.213

Hilu, K. W. (1993). Polyploidy and the evolution of domesticated plants. American Journal of Botany, 80(12), 1494–1499. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1993.tb15395.x

https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/carya-pallida/

Morton Arboretum, “Conservation Gap Analysis of Native US Hickories” https://mortonarb.org/app/uploads/2021/08/conservation-gap-analysis-of-native-us-hickories.pdf

https://www.washcoll.edu/learn-by-doing/food/plants/juglandaceae/carya.php

Grauke, L.J. 2003. Hickories. Chapter 6, pages 117-166 in Fulbright, D. (Editor), A Guide To Nut Tree Culture in North America (Volume 1). Northern Nut Growers Association.

Larson, E. L., & Kalm, P. (1945). Pehr Kalm’s Report on the Characteristics and Uses of the American Walnut Tree Which Is Called Hickory. Agricultural History, 19(1), 58–64.

Bartram, W. 1739-1822. (1791). Travels through north and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida. James & Johnson.

Homsey, L. K., Walker, R. B., & Hollenbach, K. D. (2010). What’s for dinner? investigating food-processing technologies at Dust Cave, Alabama. Southeastern Archaeology, 29(1), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1179/sea.2010.29.1.012

Hudson, Charles 1976 The Southeastern Indians. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Sheldon, E. S. (1987). Experiments and observations on Aboriginal Wild Plant Food Utilization in eastern North America. Patrick J. Munson, editor. Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, 1984. VII + 473 pp., figures, tables, references cited. American Antiquity, 52(4), 883–884. https://doi.org/10.2307/281408

Gremillion, Kristen J. (1995). Comparative Paleoethnobotany of Three Native Southeastern Communities of the Historic Period. Southeastern Archaeology 14(1), 1-16.

Fritz, Gayle J., Virginia Drywater Whitekiller, and James W. McIntosh 2001 Ethnobotany of Ku-Nu-Che: Cherokee Hickory Nut Soup. Journal of Ethnobiology 21(2):1–27

Sassaman, K. E., & Bartz, E. R. (2022). Hickory nut storage and processing at the Victor Mills Site (9CB138) and implications for late archaic land use in the Middle Savannah River Valley. Southeastern Archaeology, 41(2), 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0734578x.2022.2033450

Miller, B., & Bassuk, N. (2022). Carya species for use in the managed landscape: Predicted drought tolerance. HortScience, 57(12), 1558–1563. https://doi.org/10.21273/hortsci16756-22

Au, T. F., & Maxwell, J. T. (2022). Drought sensitivity and resilience of oak–hickory stands in the eastern United States. Forests, 13(3), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13030389

Nowacki, G. J., & Abrams, M. D. (2008). The demise of fire and “mesophication” of forests in the Eastern United States. BioScience, 58(2), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1641/b580207

Radcliffe, D. C., Hix, D. M., & Matthews, S. N. (2021). Predisposing factors’ effects on mortality of oak (Quercus) and hickory (Carya) species in mature forests undergoing mesophication in Appalachian Ohio. Forest Ecosystems, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-021-00286-z

Au, T. F., Maxwell, J. T., Novick, K. A., Robeson, S. M., Warner, S. M., Lockwood, B. R., Phillips, R. P., Harley, G. L., Telewski, F. W., Therrell, M. D., & Pederson, N. (2020). Demographic shifts in eastern US forests increase the impact of late‐season drought on Forest Growth. Ecography, 43(10), 1475–1486. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05055

Rose, Anita K. & Rossin, James F. “The Importance and Distribution of Hickory Across Virginia” US Forest Service, Southern Research Center, Knoxville, TN.

Do you have any specific recommendations for processing bitter hickories? I have made kanuchi, nut milk, and nut butter with shagbark hickories, but when I tried to make nut milk with bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis) it was still very bitter after an hour or so of boiling. I also tried adding salt which did not seem to do anything.

Also, have you given much thought to fire regimes prior to human presence in North America? I am really curious to know what things looked like in the prior interglacial (Eemian) but to my knowledge there isn’t any good data on that. However, I have got to believe that hickories and oaks were still dominant across much of the landscape without human presence, given their diversity and the number of species that depend on them. At the same time, I think that without anthropogenic fire, the fire frequency would be much reduced in eastern forests outside of the sandy coastal plain. Perhaps megafauna played a big role in maintaining oak and hickory forests, but I don’t think we have any knowledge of that. I know that during the last glacial period, oak was less prominent in a lot of areas.