John W. Hershey

The engine behind the 20th century tree crops movement

We’ve talked about the role of J. Russell Smith behind the development of a comprehensive tree crops movement, and in his most famous book, Tree Crops— one name pops out repeatedly for the research that they were doing; John W. Hershey. While John’s work lives today through both what remains of the Downington Food Forest and the work of folks like Zach Elfers, Max Paschall, Buzz Ferver, Pete Chrisbacher, and more who have worked tirelessly to save the genetics of the trees from his former orchard, a google search for John’s name only pulls up a few scant articles— typically his name in passing in regards to either his nursery, the Tennessee Valley Authority, or J. Russell Smith. While wildly incomplete, the goal of this piece is to provide as much of a comprehensive piece on John’s life and work, one which otherwise does not exist.

Because of the limited information that exists in books, pamphlets, and news articles (to put this article together required multiple pamphlets with limited access, which have been since scanned into PDFs which we will make publicly available), this piece will likely change over time (and that’s a good thing because it means we’re learning new information to give a more thorough history of his life). That all said, every project begins with a first step, and that’s what we’re doing here.

No pictures exist of John W. Hershey if you do a Google search (but, of course, as you can see above, they do exist, with the right resources). In fact, in all of the documents I was able to find, none had a correct birthday for John Walter Hershey, whose birth certificate is on record in Lancaster county as February 5th, 1898 to John Krieder Hershey and Mary (Maize) Hershey. John’s father was also a farmer and influenced him from a young age.

Nothing is recorded about John’s life as a child, except his interest in farming and his Mennonite background. He once said that he grew up on a farm and that “diversified farming was our salvation.”1 Early in his career, he was fortunate enough to connect with John F. Jones, a tree crops legend who had come from Louisiana. Jones saw passion and potential in young John and became his mentor, as young John worked on his tree nursery and eventually made connections with other figures in the tree crops world, including the man who would become his close friend, J. Russell Smith, who he often described as a godfather-like figure. John married his wife, Elizabeth Kitch, in 1925, at the same time he started developing his own nursery on 8 acres on the east end of Downington, PA (technically in 1924, according to John, but if you ask his wife Betty, it was 1921), a small space he would quickly outgrow.2,3 It wouldn’t be until almost a decade later that he would have stock to sell, which was in 1932.4 It was also around this time John and his wife adopted their daughter as a baby, named Catherine Mae Detterline— whom they dotingly called “Kitty”.

His early years with his nursery were tough— the land he had purchased across the street from the Quaker meetinghouse was “sick and lifeless, two to four inches of top soil and lots of stones. I didn’t know much about soil robbing then, so I didn’t know my soil was sick.” His solution was to use horse manure to quickly improve the nutrient profile of his soil, which caused his black walnuts to be covered with cat’s eyes disease while leaf hoppers destroyed his English walnuts. Slowly, he learned to apply cover crops, such as soybeans, scything the plants and other weeds down, keeping a permanent green crop of beans or oats to feed the soil. It wasn’t until nearly a decade later, that he began to incorporate leaves for mulching (1934) and even began trucking in leaves for compost— around 1938 he was trucking in “65 to 70 large dump truck loads”.

John was drawn to the “Bio-Dynamic idea”, moving away from conventional fertilizers and relying only on the occasional dry blood or raw bone. However, he was known to, in the late 40s, use “soupy dog manure from the hunt club” as well as “five tons or more of backhouse material (human waste)”. By 1943, his two-to-four inches of topsoil measured eight to twelve inches deep. At first, John largely used chickens for insect management on the farm, but later switched to ducks, as they had no problem devouring Japanese beetles. John leveraged native cherries to draw caterpillars away from other trees. The soybeans kept the rabbits from eating his hazelnuts. John didn’t start selling trees out of his nursery until 1932.

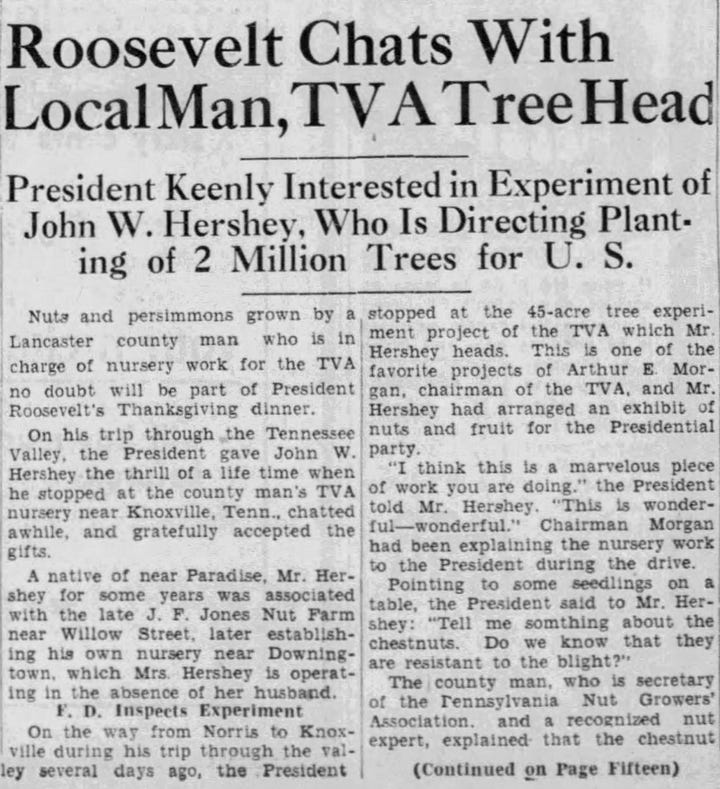

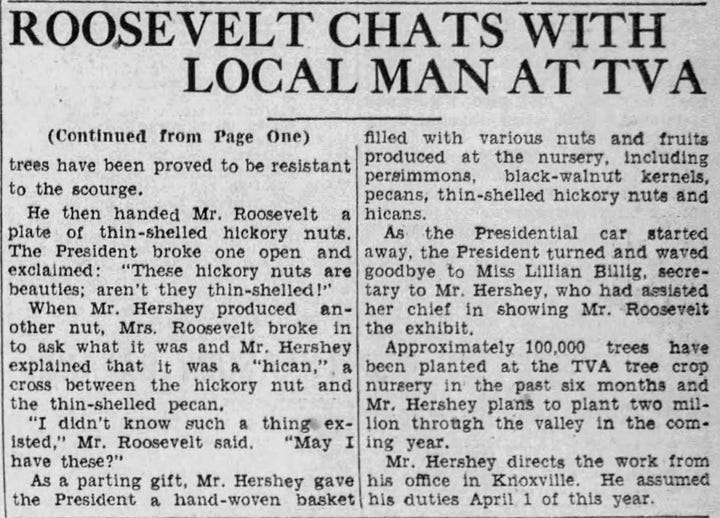

To back up— the late 1920s was a tough time for John; his daughter Patricia Ann Hershey died shortly after birth in 1927 & his son John K Hershey died in 1928 shortly after his birth. J.F. Jones, his mentor would also die unexpectedly in 1928. The late 20s and early 30s were a formative time for John; he would begin writing and making the connections that would be so valuable for the trajectory of his work. One of these moments was the development of the Tennessee Valley Authority, under the guidance of President Roosevelt in 1933. Arthur E. Morgan, the man who oversaw much of the agricultural and forestry parts of the TVA, had wanted J. Russell Smith to head the tree crops component of the project. John Hershey accepted and in April of 1934 left the nursery in the hands of his good friend John Pannebaker.

The TVA years

Not a formally trained forester, he stood out of place among legends in their fields— Dr. Ernest J. Schreiner (who was a foremost expert on tree genetics) and J.C. McDaniel (who’s best known for Magnolias, but did work with Hickories and has a variety of Kentucky Coffee Tree named after him), which made him seem out of place. The Tree Crop Nursery was near the Norris Dam in Tennessee, and he worked alongside Harry Steward, who also had been tutored by J.F. Jones, and together they worked to harvest nuts from the best trees in the valley and oversee their team of planters. John worked with native and nonnatives, including jujubes, che, persimmons (both Asian & American), hickories, pecans, honey locusts, blueberries, and even oaks.

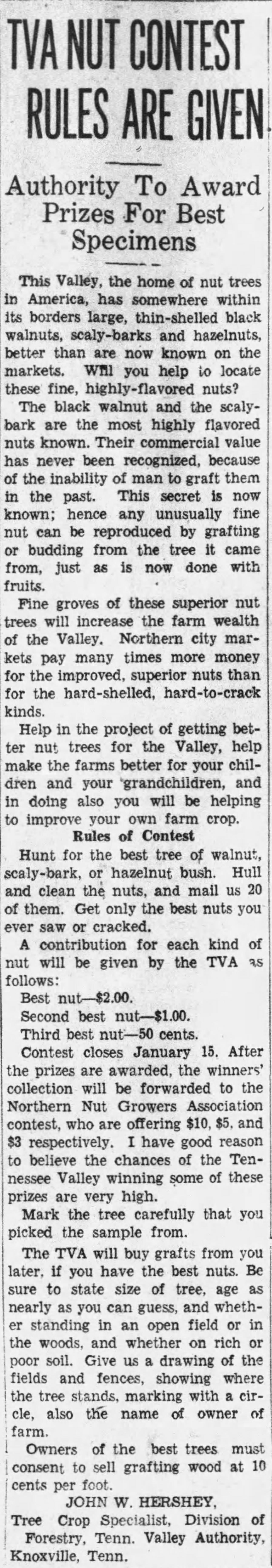

The project was wildly visionary, it was the first forest breeding project on this scale in the world. To collect genetic material, the TVA ran contests for all of their crops— sweet acorns, honey locusts, persimmons, and more. Many of the discoveries made from these contests can be found in tree crop catalogs today— and many of those selections were the result of generations of breeding work by indigenous groups— such as the Cherokee, who had used the honey locust, for example, as a sugar crop.5

The competitions were based on the successes of similar collaborations that J. Russell Smith devised with the Journal of Heredity in the 1920s. For John & J.R., the competitions didn’t always run smoothly. For example, the first contest for a sweet honey locust was won by a woman in Villa Rica, Georgia. Smith had requested scionwood from the woman, who obliged, but the grafted trees didn’t bear any pods. He passed along scion to John Hershey, who planted some at the TVA, only to discover the scions were male. When Smith investigated the origins of the scions, the woman who won the prize admitted that she didn’t actually know which tree the winner came from, that the pods were from “over there”, pointing to a row of honey locusts. When pressed on the tree shown in the image with her contribution, it was an entirely different tree because they had wanted a picture of a honey locust, and the scionwood came from the tree with the lowest hanging branches with no bearing on which provided the pods that had one.

The vision of the Tennessee Valley farmer was to be similar to many farmers in places like the Iberian peninsula, where the farmers would rely on healthy ecosystems built up by managed tree plantings to feed livestock and the community. Unlike most federal entities, it was responsible for a region rather than a single project— and even had its own authority to buy land and implement its own proposals, meaning folks like John were given the ability to exercise his professional opinion without being weighed down in red tape. Further, the TVA was expected to address a number of human rights and ecological issues simultaneously— flood prevention, soil conservation, power production, and the redevelopment of rural economies. It initially was to address the issues of flooding from the Tennessee River, which was to be managed through dams that would provide power to the region while also developing long-term ecological solutions to mitigate the worst of any flooding through soil stewardship.

The architects behind the TVA believed that they would be able to use the TVA as a model for regional planning—that it would highlight the ways the new modern rural economy could thrive under the weight of government organizing and progressive policies— what Leo Marx described as the “pastoral ideal”.6 The vision was one in which rural communities embraced and leveraged technology for improved material conditions while not destroying nature to the extent that conventional farming practices that led to the Dust Bowl did.

This movement was led by the work of folks like Ebenezer Howard & Patrick Geddes, who wrote about ‘garden cities’ which would be the blueprint for the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA). The Garden Cities vision was tinged by competing board members Arthur Morgan, Harcourt Morgan & David Lilienthal, who fundamentally disagreed about the role of state planning, democratic rule, and reconciling the needs of poor white rural farmers with the poor black urbanites just outside the range of the TVA’s jurisdiction. While Arthur Morgan was the one who hired Hershey, it would be Harcourt Morgan who would oversee the land management aspects of the TVA.7

That said, Arthur was invariably interested in tree crops personally and maintained an open line of communication with John. When Arthur would talk about using forest genetics for plastic and chemistry, John replied “My goal is to find select ‘tree crops’ to be planted on the unplowable hills of America, so that when our complex economy breaks down the individual will have a little more ease in standing the strain of having to go back to a self-sustaining plane of ‘just living’ as our forefathers did and as EVERY OTHER people did when the pressure of cultures on the soil broke its back and the artificialities of materialism receded in decay.”8

The TVA managed two tree nurseries, one at Clinton, Tennessee and one near Norris Dam— the second of which John oversaw. The scale of the nursery is hard to imagine— they were working with millions of trees and were sharing resources freely with the public— including seedlings. The program’s investment included maintaining new seedlings for five years at no cost. It was estimated that for full reforestation of the Tennessee Valley, the nurseries would need to produce 800,000,000 seedlings.9

The Clinton Nursery was geared to supply fifteen million seedlings annually while the Norris Tree Nursery was specifically designed to develop a tree crop agriculture on the hilly lands of the Tennessee Valley. The Clinton Nursery focused primarily on black locust, spruce, and pine trees to stabilize soils while Hershey focused on identifying improved genetics for tree crops. This meant less-tannic acorns, sugar-heavy honey locusts, disease-free jujubes, and the thinnest-shelled walnuts, hickories, and pecans, just to name a few. Little has been written about the Norris Tree Nursery, and it’s largely been considered an overall failure for its inability to implement any long-term changes to the role of tree crops in North America, but it was a starting point for many of the cultivars and varieties that exist today, as we will discuss.

Betty Hershey discusses why she thinks the Experimental Tree Nursery failed (1980).

However, the tree conservation project as a whole was not a failure. From the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) data, the 1941 annual report stated that the Tennessee Valley nurseries “during the past year over 13 million young trees were planted on 1,043 erosion projects on over 9,000 acres of severely eroded private lands”.10 While well short of the estimated 800 million, tens of millions of trees made it into the ground over the life of the TVA project and many still exist today.

Part of the reason of the Norris Nursery’s failure was due to John’s incapacitation. In 1936, John was diagnosed with stomach cancer, and he spent 11 weeks in Philadelphia in the hospital. Afterwards, he continued to work, despite his limited physical capacity. By 1938, he began to transition back to Pennsylvania, staying as a consultant until 1939.

Greg Williams talks with Betty Hershey about the demise of the TVA Tree Crop Program.

While John’s primary work was to breed trees, he also worked to write about their findings. He took this opportunity to write about why trees were important and became an advocate for not just the trees he was breeding by anything he felt was important for the success of tree crops. For example, in 1934 he wrote a bulletin about the planting of woody winter-bearing fruits for wildlife, since birds were so necessary for insect control in his biodynamic farming system. This later was picked up by forest management and game authorities and influenced how game authorities managed for wildlife and hunting, something which John was passionate about as an avid pheasant hunter.11

The Birth of the Downingtown “Food” Forest

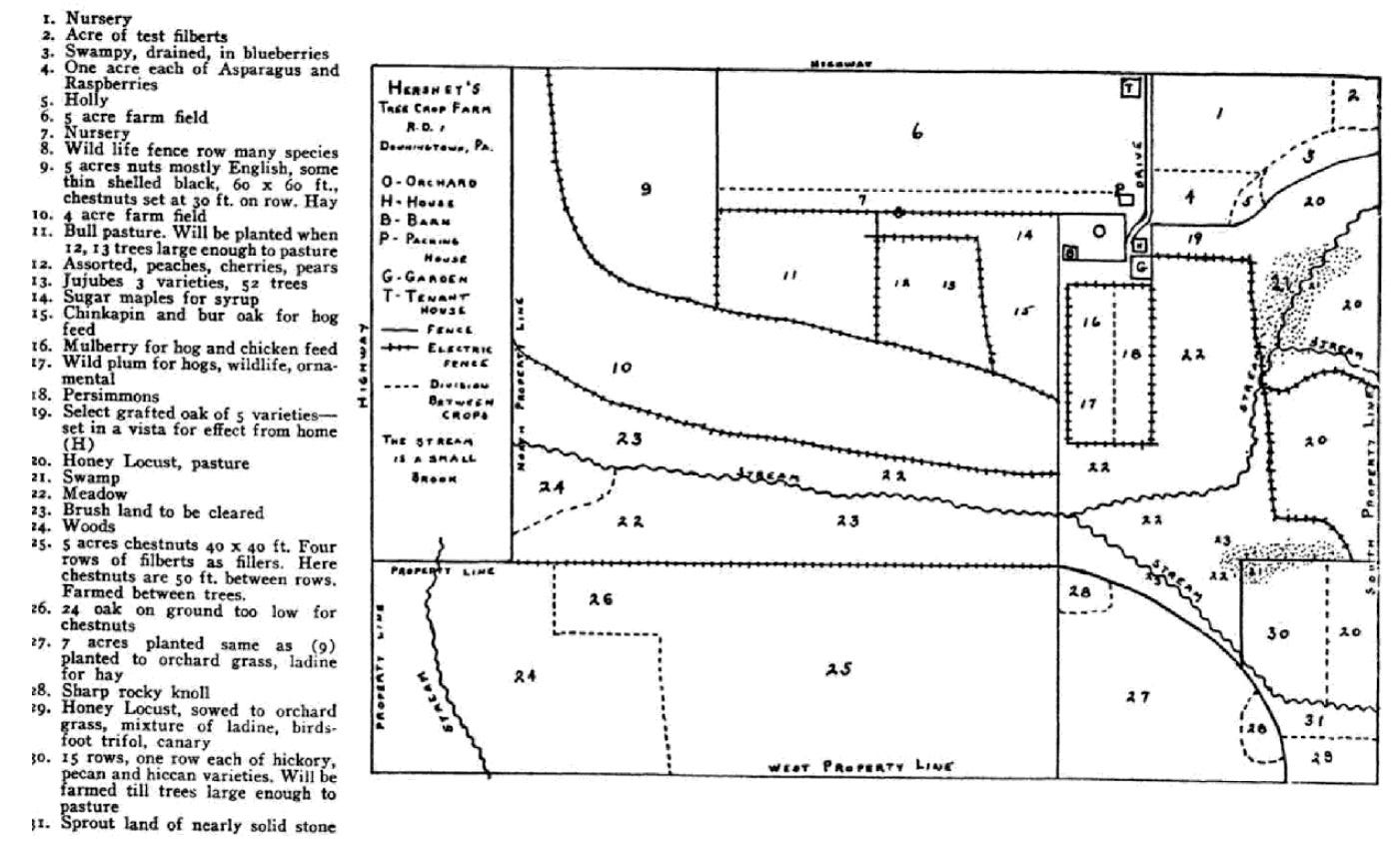

Returning home, the size of the original farm seemed limited after having access to the resources and scale that he was working on with the TVA. From 1939 to 1944, John continued to build his catalog of material so that when the opportunity arose, he could quickly move it into the vision of a forest farm that he had begun to visualize in Tennessee.

It was on January 16th, 1945 when he and Betty bought the farming in Downington— the location now known as the former site of the Downington Food Forest. The seventy-two acres offered him a template to apply all of the things he had experienced at his first nursery and in Tennesee and was a place for him to graft scions from many of the best selections from the TVA collections.12 The new farm had been destroyed by petrochemical fertilizers and he spent the first few years bringing in compost, manures, humanures, cover cropping soybeans, and oats. Wanting to stay away from chemical fertilizers, he tried to find raw crushed rock to bring into his farm for phosphate. He was told it was no longer available but was able to find companies in Tennessee who would sell it to them by the truckload, which he brought back to Pennsylvania.

Nature is a balanced force, soil undisturbed is a delicately balanced flour barrel of never ending life. Learn of nature how to protect this soil, that shallow insulation board between man and disaster.13

Here, he planted black walnuts, English walnuts, oaks, pecans, hickories, hicans, chestnuts, filberts, hazels, persimmons, honey locusts, and mulberries for propogations. He also included other trees and plants for ecosystem benefits. He also took his experience to pen, becoming a prolific writer, advocating for the return of tree crops and highlighting the potential use for many of these crops— suggesting that we need more “acorn-fed children”. He framed the need for nut trees from a practical and a philosophical perspective with a vicious optimism. In “Why People Don’t Plant More Nut Trees”, he states that:

The so-called depression has truly brought the American people out of their wild and glamourous orgies to clearer political realization of the necessity of the conservation of natural resources. I want to say again, that although from the hurried Americans’ yardstick of measurement the tree crop nurseryman may not get immediate results from this depression, I do know that they will all be better off for it."

John’s annual reports during his time at the Downingtown forest point to the fact that much has yet to be discovered— in 1948 he discusses a “blackberry tree” from northern Texas, and an improved Honey Locust variety of “Schofer”, similar to Calhoun and Millwood with better hardiness.14

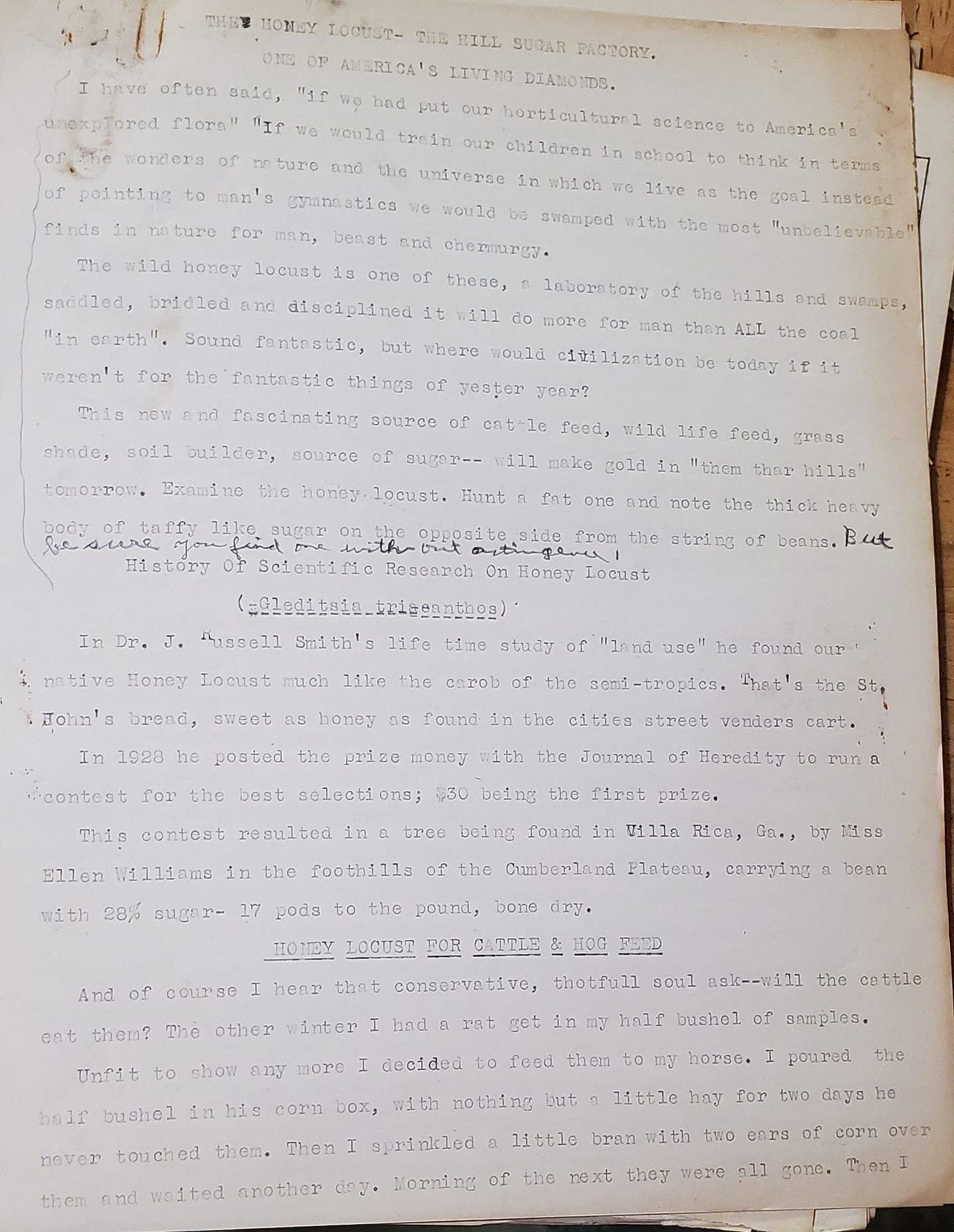

There’s still much research to be done and there is more information coming out about John’s writing work, including a recent manuscript titled “The Honey Locust— The Hill Sugar Factory. One of America’s Living Diamonds” that had been kept from destruction by Greg Williams.

In this book, he discusses various first-hand reports of people using honey locusts for feeding cattle, pigs, and kids roasting the pods to eat, and even using the honey locust for making good beer! He also describes his current farm, which was “robbed by carpet baggers for 12 years” before he could restore the soil. He also highlights some of the discoveries made processing honey locust pods— that most of the bitterness of the pods came from the ‘stalk’ that surrounded the beans, and that the “fine powdery dust” contained much of the sweetness and very little bitterness. He further describes J. Russell Smith’s experiment processing the locust pods for sugar and using it for baking with much success.

His stories weren’t anecdotal— they were based in his own work. As recalled by Betty Hershey:

Some of the pigs and mulberries, John liked mulberries to, you know, we had very good mulberries, all of their snouts would be all full of mulberries. And if you wanted a persimmon you had to get out early in the morning or the horses or cattle would clean them up. And the acorns, the cows would eat the acorns, and the honey locust seed, that’s good feed.

It’s worth noting that John didn’t always see eye to eye with many folks in the permanent agriculture space, to his detriment. A religious man first, he was quick to criticize other folks in the permanent agriculture space for having differing cultural values and even politics from his own, stating, for example:

Every person who takes a subsidy from the government; be he farmer, industrialist or the lousey unionist who demands a bigger rake off than he earns. YOU, the individuals who’s taking it, are all in the prostitutes class… One thing I know for sure, such “libertinism” killed Rome and it’ll do the same to us. The brainwashing of communism is peanuts along side the soulwashing of our materialistic educational system. It’s pathic to hear the stream of condemnation on communistic slavery while emeshed “to strangulation” by the gods of OUR choice. THOSE CULTURAL MEDDLERS: Then there’s the group’s of well wishers, social uplifters, doergooders who would have OTHERS live the right way while THEY continue to live in Sodom and Gohmarr. These are banded together under such titles as “The Country Life Association”, Friends of the Land, Health organizations and Organic Gardening groups.

Some of his writing would fit into modern right-wing news rags— in an annual update on his farm, he complains about the government learning to live within its income and not the taxpayer— that people need to “leap from their asses” instead of waiting for handouts, and repeatedly misconstrues Science with the interests of capital.

His self-published book “Nature’s Orbits Man’s Profit” leads with: “This is an account of the Capitalism of Nature; of God’s Hand-Craft, in Forest and Farm, so there might be on record, a declaration of the yard stick of measurement for human behavior.”15

In it, he describes the oak, walnut, and hickories as the “pillars of nature capitalism”, and that the squirrel, for example, “is a true capitalist” because “he gathers more nuts and acorns than he needs”, and those he doesn’t need he “deposits them in the bank of nature for future dividends”. The problem, according to Hershey, is always the government and the “professional minds”, as he puts it— the scientists and conventional farmers.16

The pamphlet continues along these lines— equating the Kudzi vine to “communistic strangulation” (even though he has advocated for autumn olive in his writing) and that natural methods can cure cancer— it’s a vivid intersection between the biodynamic philosophy and capitalist talking points highlight much of the narrative that drove John’s work on his farm. His experiences (and failures) with both the TVA and making his own farm profitable left him angry in all directions, and given his politics it’s interesting that he was so close to J. Russell Smith, and points to his radicalization being reflective of his older age.

In 1958 John spent 6 weeks in the hospital where most of his stomach was removed, and it would be several years before he regained any semblance of normalcy. His daughter, Catherine, alongside her husband Sam, kept the nursery going. After a decade, many of the saplings John had planted began producing crops— nuts and fruits and honey locust pods. Pigs, horses, cows, and fowl devoured the fresh produce.

In 1963 during the Christmas week, the main barn burned down. Alongside the other struggles of nursery management and his health, John closed the nursery and focused on the Tree Crop farm, hoping to turn it into an arboretum, which almost materialized— the biggest challenge was lack of funds. The original plan had been for the Brandywine Valley Association to acquire the property, but the funds ended up being diverted for another project.17 During this time, he released his self-published book.

By 1965, John began to lose the physical capacity to steward the landscape. The infamous Downington Forest was sold off in the 1960s, and the developer had agreed initially to leave the trees, which he quickly ignored after the sale of the property. On September seventh, 1967, John passed away.

The Post-Mortem Forest

While suburbanization may have stolen the purity of the forest the Hershey family developed— the heart remains. Throughout Downingtown, evidence of the forest is scattered across the suburbs— specifically, the Villages at Timberlake. As interest in tree crops has grown, so has police presence as folks have shown up looking to save the Hershey genetics, at the cost of the land owners. It’s because of this even the most passionate tree crops advocates don’t recommend visiting the site looking to score scion or seed.

However, John’s work can be found elsewhere throughout the area, as he was prolific in sharing the good word of tree crops. A persimmon tree stands outside of the Downingtown United Methodist Church— seemingly out of place. More of his trees stand outside Bishop Shanahan High School and more. While names change and new subdivisions are built up, many of these trees have continued to quietly produce fruits and nuts that are unparalleled across the globe.

But the list of survivors continues to shrink with each passing year. One of the biggest developers in the area is looking to built luxury apartments on 15 acres of land once owned by the Archdiocese. At the efforts of tree crops advocates, they were able to save seven of the older hicans and pecans. The builder has shown no interest in the remnants of John’s work— in his words: “We’re always planting more trees than we take out. We take down the big trees and put in small ones,” almost comically aloof to the significance of the tree genetics.18

Betty Hershey discusses leaving the farm in an interview stored by Greg Williams, made available by Zach Elfers, and edited by Dominic Guanzon.

The home still stands, albeit with an addition and many plants John may not have advised to plant— but it’s still there. In the front yard stands a grafted heartnut tree, a testament to the time that has passed since John’s humble hands had worked the once-stripped soil.

What’s particularly important to understand about these trees is that they’ve continued to produce quality nuts and fruits for nearly 7 decades now without any maintenance— despite climate change, despite changing ecological conditions from suburbanization, despite all of the other challenges facing our neighborhoods today they still stand and produce, year after year.

Fortunately, the battle to save these trees is fought on several fronts. In a field of a 100-acre park off the Lehigh Valley Thruway, Louise Bugbee has been slowly working to protect the genetics of Hershey’s farm. Buzz Ferver’s farm in Vermont likely has more genetics from Hershey’s farm than anywhere else on Earth. The work to save, document, and advocate for John’s work— and the work of the indigenous communities that had bred many of these plants for thousands of years— continues on, with or without attention.

This particular piece couldn’t have happened without the help of Zach Elfers, Max Paschall, Taylor Malone, Buzz Ferver, and others to help fill the gaps and to provide key information to tease out fact from fiction when it came to John’s history. My hope is this will be a starting point for further research— what more can we learn about his time at the TVA? Where else can we find his trees? Do we know of any folks who bought large volumes of trees from John? And so on.

It is my full hope and expectation that this piece is reworked and reworked as new pieces of information come out. Please, please if you have something to contribute, let us know so we can continue to build a better understanding of John’s history and his work.

A few more resources:

Nutty Buddy Collective visits Norris Dam

Man in his progress of the last century nearly ruined the climatic balance by wrecking the forests and soils of this great and productive continent.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 18-page chapter, of (so far) a 959-page book with 636 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this episode, #201, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. Suppose you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content. In that case, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Hershey, John. “My Responsibility as a Citizen in a Free Economy”, September 1955. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Bt7w5HrKqTiFr4sG1Z2vq2wfdTNpafWr

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f2ffa8a33f50e61c794374d/t/5f6ebc6d4ca040062e756a4c/1601092796517/Biodynamics+Journal+Issue+%2313+%281948%29+-+Article+by+John+W.+Hershey.pdf

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f2ffa8a33f50e61c794374d/t/5f6eb4fe36b37d25b6cea260/1601090855401/John+Hershey+Biography.pdf

Undated recording of Betty Hershey, from Greg Williams’ archives, made possible through Zach Elfers & the editing work of Dominic Guanzon.

You can learn more about this history in our interview with Dr. Robert Warren at SUNY Buffalo here:

Marx, L. (1979). The machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. Oxford Univ. Pr.

Sachs, A. (2023). The garden in the machine: Planning and democracy in the Tennessee Valley Authority. University of Virginia Press.

Hershey, John. “Progress report for 1946”. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Bt7w5HrKqTiFr4sG1Z2vq2wfdTNpafWr

Hawkes, C. L. (1937). The Forestry Program of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

“Annual Report of the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1941 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office), 37.”

Hershey, John. ‘Doing It’ Versus ‘Talking About It’. Coatesville Record 1961. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Bt7w5HrKqTiFr4sG1Z2vq2wfdTNpafWr

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f2ffa8a33f50e61c794374d/t/5f6ebcf80a75e61a51988d07/1601093208982/Hershey+Acorn+the+Mountain+Corn+Crop.pdf

Northern Nut Growers Association, 38th Annual Report, September 1947.

Hershey, John “Progress Report on America’s #1 Tree Crop Farm” October 2, 1948 https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Bt7w5HrKqTiFr4sG1Z2vq2wfdTNpafWr

Hershey, John. “Nature’s Orbis Man’s Profit”, 1957. file:///Users/andycerrone/Downloads/Nature_s%20Orbits_%20Man_s%20Profit%20(1964)%20-%20John%20W.%20Hershey%20-%20Pamphlet%20Layout.pdf

https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=ksvy0215

https://sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/forests-of-the-future/

https://web.archive.org/web/20221127014812/https://www.phillymag.com/news/2018/07/07/downingtown-food-forest-urban-farming