From Mastodons to Modern Times: The Tale of the Kentucky Coffee Tree

The poisonous-not-poisonous mastadon pea

The landscapes of the Americas are littered with what’s called anachronistic trees; species that coevolved with megafauna that once were the primary distributer of seed and genetics. With the passing of those massive mammals, from the late Pleistocene extinctions— a perfect storm of climate change and human expansion— their slow passing on the landscape has been outside of the scope of human tools of measurement.1 Hidden away on the landscape are large, strange fruits that go uneaten by wildlife— pawpaws, honey locusts, osage oranges, black locusts, and Kentucky coffee trees.

While we picture the megafauna meaning the mastodon and wooly mammoth, oversized beasts similar to many of the larger species of Africa once called North America home— sabertooth cats the size of lions, bear-sized sloths called Nothrotheriops, car-sized armadillos called Glyptotherium, and so many more. These monstrous animals demanded larger foods, and the fruits and seeds they feasted on found themselves alone after their rather quick extinction. While many disappeared quickly, those few that remain stand out in a landscape they never evolved for. But many found new mates with the primates who repopulated the landscape.

The Kentucky coffee tree is one such plant. As humans learned the landscape, these oversized fruits and seeds offered a massive caloric input, if they could be processed. Today, the seeds are largely considered inedible. Yet, the trees are almost always found near Indigenous settlements.2 So the question remains; if they are inedible, why were they so revered that they were planted so close to home?

Borrowing from my good friend over at Pyrophytic Futures (who has written about KCT, which I’m borrowing from extensively— subscribe to their great work!), there’s quite a bit to unpack about this unique tree. Before we can discuss its historical role with humans on the landscape, let’s look at the bean itself.

Right away, it’s obvious that it’s a bean— it dangles from the trees in green pods that look like comically oversized snap peas, and the beans themselves are nickel to quarter-sized. By most researchers, they’ve been considered both toxic and inedible. Similar to other anachronistic trees (such as black locusts), livestock have been reported to have been poisoned not just by the beans but the leaves as well.3 The chemical that has been the focus of the research regarding its toxicity is alkaloid cytisine. Alkaloids contain nitrogen, taste bitter, and are often poisonous to animals. However, there’s never been cytisine found in the beans— but that doesn’t mean that there are no other compounds of concern.

One researcher, in his quest to prove the cytisine content of the beans, stumbled across a new chemical alkaloid named diocine, that is structurally similar to caffeine.

And for a more detailed explanation of how diocine works, I’ll defer to Pyro:

Diocine appears to degrade during cooking into the stimulant paraxanthine - the main chemical produced as our livers break down caffeine - which is known to be fairly safe. However, it takes two breakdown steps to convert diocine into paraxanthine. Those breakdown steps are where some risks may be hiding.

Diocine itself is what’s known as a derivative of 1,7-dimethyl-isoguanine (which is one of many isoguanine compounds we know of) . The term derivative describes compounds that are structurally similar or can be converted into one another via chemical processes - and so diocine can be considered a potential source of isoguanine compounds. Isoguanines are important to think about when evaluating food safety because they have potential mutagenic (can cause harmful mutations) and other genetic / carcinogenic effects.

As diocine breaks down into the stimulant paraxanthine, it first degrades into the isoguanine derivative 1,7-dimethyl-isoguanine. That means we’re at risk of consuming these potentially toxic compounds if the cooking process doesn’t fully break down all of the diocine.

Consulting with chemists has led us to believe that 1,7-dimethyl-isoguanine is less likely to be mutagenic (and therefore dangerous the way isoguanine is known to be) because of certain structural features. In chemical terms, the methyl group on the N1 group prevents base pairing and thus mutagenic mechanism. The methylation at the 7 position makes it difficult to incorporate a sugar chain there, making it less likely to be processed into RNA or DNA like structures.

Instead of pure isoguanine, 1,7-dimethyl-isoguanine is more likely to act on the parts of our body caffeine does - like the signaling system related to sleep, movement, and eating (the purigenic receptors). The paper on diocine also mentions other unidentified chemicals (methylpurines) present. We don’t know what they are or what their effects are.

In short, the compound in the beans breaks down when cooked into something similar to caffeine, but first, it switches into a potentially dangerous chemical. However, there are still other chemicals that are understudied in the beans that have the potential to be harmful. This trait— the caffeine-like compound— also explains the name of the tree— as it was often described as a poor coffee substitute for colonists as they expanded west. It was actually a selling point; Kentucky was “a place where a tree grew with beans that could be roast and brewed to make a fine coffee substitute.”4 Anyone who has tried this drink will tell you that this is not the case. In fact, in 2003, researchers decided to recreate written recipes to make coffee from the Kentucky Coffee tree.5 According to the test results, “No one claimed to enjoy the taste or the experience.”

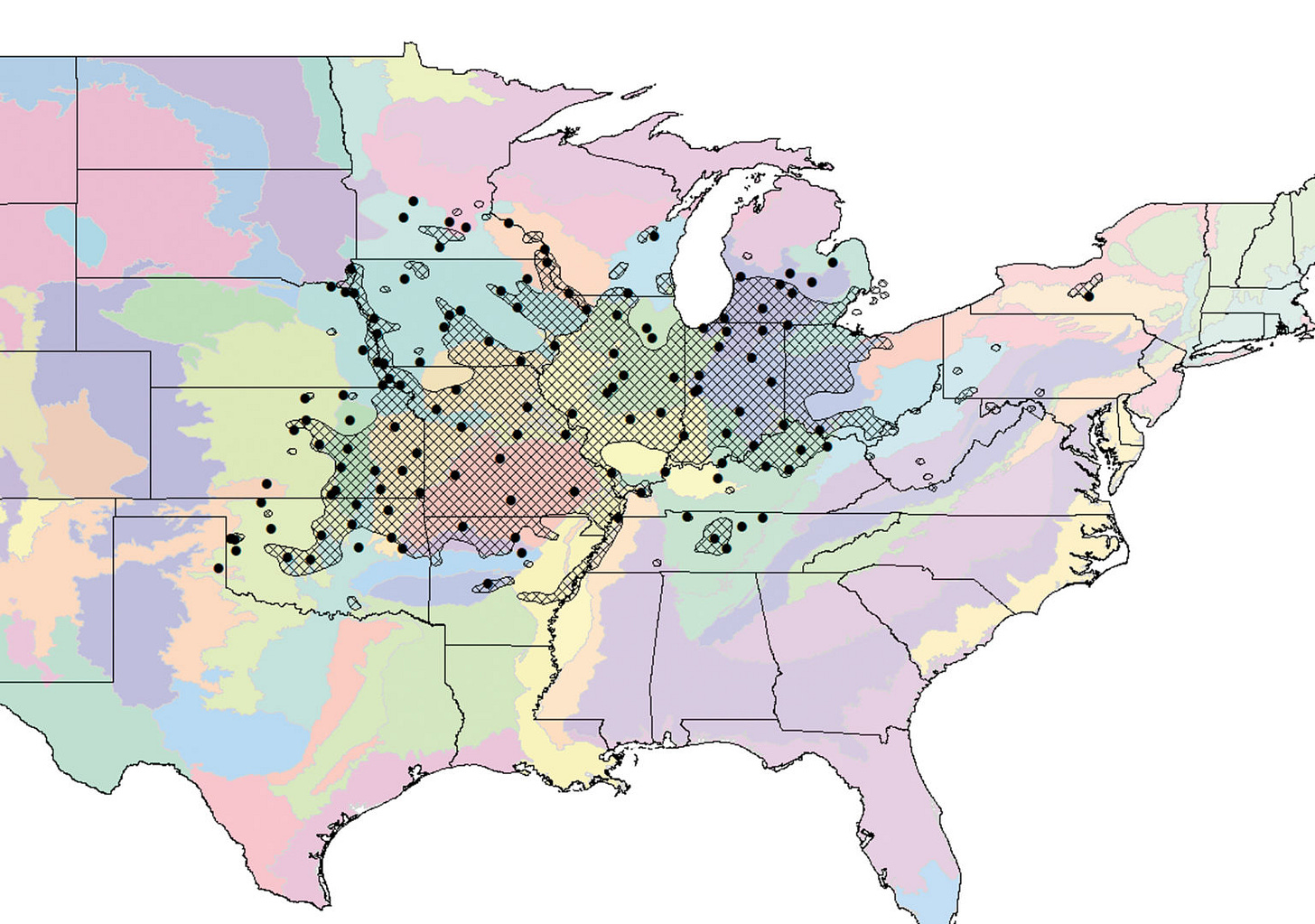

The range of the Kentucky Coffee Tree is quite limited today, as evidenced by the graphic above. Historically, it has been assumed that the tree grew primarily near wetlands, which is where it has been found most often. However, researchers have noted that despite the majority of specimens being in these wet bottomlands, it was the trees planted on drier sites that were healthier and grew larger than their wet-toed counterparts.6 The reasoning for this was simple— it was only in these wet environments that any seeds with cracks on their thick shells would germinate. Without the rumens of the mastodons, the seeds are left undisturbed and incapable of germinating on the landscape. In some cases, these seeds pile up for years, untouched by rodents, mammals, or anything else. What this means is that they are not growing in wet regions by choice but rather by necessity.

This brings us back to the point that these trees, which are difficult to propagate, were found near most Indigenous settlements across the Midwest and mid-Atlantic. While the Kentucky coffee tree does fix nitrogen, as it is a pea family member, it does so at “much lower rates than modulated legumes.”7 With that in mind, it was unlikely grown for its nitogren fixation.

What we do know is that at least some Indigenous communities used them as a food and medicine source. Several sources suggest that the seeds were roasted and eaten, but nothing more is written on this specific use.8 To do so, they must be roasted at 150 degrees Fahrenheit for at least three hours to be safe for consumption. It is reported that the pulp was used as well for medicinal uses, similar to how the pulp of honey locusts was used as a food source over the beans.

The primary draw according to historical documentation is that the beans were used for recreational and ceremonial purposes. A dice game which centered around the beans has been documented in nearly every Indigenous community in the modern United States, suggesting that the game— which went by many names (platter, hubbub, Paquessen, dice, bowl-and-dice, women’s dice) was significant. That said, I highly doubt the tree would be kept in such close proximity for the occasional dice replacement.

While variations of the game exist, the most common variation is that a blanket is spread out on the ground and a group of players sit around it. Two sides were needed. Each player took turns tossing the dice by either throwing them upward out of a bowl and catching them again, or by throwing them against a hide or blanket that was held perpendicular to the ground and allowing them to fall, where they were scored.9 The score of each roll was determined by counting the number of dice of one collar and assigning points based on a scoring system.10

However, it is noted that Kentucky Coffee Tree pods weren’t the only seeds used for this game— plum seeds, persimmon seeds, acorns, grains of maize, and more were often used.11 Simply put, the idea that the tree was celebrated simply for being part of this game isn’t sufficient. In Gordon Day’s words,

There appears to be an association of American chestnut, Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh., groves and Indian village sites in lower Ontario, and Jury (1952) is inclined to the opinion that the trees were planted by the Indians. The Iroquois of New York planted the Canada plum, Prunus nigra Ait., and possibly Kentucky coffee tree, Gymnocladus dioicus (L.) K. Koch, since it is most often found near village sites.12

Today, folks like Alan Bergo & Alexis Nikole Nelson are learning how to work with what they’ve dubbed “Mastadon Peas”, a homage to their ancient collaborators. Their methods are fairly straightforward— roasting mature beans or boiling immature beans. Our friends over at Pyrophytic Futures experimented with nixtamalizing the beans with success, making the hard shell turn into a waxy rubber that could be easily peeled away.

Fundamentally, in many ways, the ‘Mastadon Peas’ are similar to many beans that we prepare commonly today. That said, we still do not have a full understanding of the chemical effects of many of the novel compounds within the beans. That said, the benefits of further research are astounding. These are perennial, nitrogen-fixing peas with high protein content that is at no risk of pest or grazing pressure.

The trees also leaf out later in the spring— reducing the risks of late frosts that are more and more common under climate extremism. And speaking of extremism, the trees thrive in zones 3 through 9; they’re as much at home in northern Maine as they are in Texas. Their capacity to handle extremes puts them way ahead of many trees we rely on today to feed us, while asking for no irrigation, pesticides, or breeding work. It only asks that we keep it alive.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 9-page chapter, of (so far) a 1299-page book with 968 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #247 of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Barlow, C. 2008. The ghosts of evolution: Nonsensical fruit, missing partners, and other ecological anachronisms. New York: Basic Books.

Zaya, D.N., Howe, H.F. The anomalous Kentucky coffeetree: megafaunal fruit sinking to extinction?. Oecologia 161, 221–226 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-009-1372-3

Evers, Robert A. (Robert August), Roger P Link, and L. R. (Leo Roy) Tehon. Poisonous Plants of the Midwest and Their Effects on Livestock. Urbana, IL: Distributed by University of Illinois Press, 1972. Print.

https://www3.uwsp.edu/forestry/stujournals/documents/na/avannatta.pdf

https://archive.org/stream/biostor-159967/biostor-159967_djvu.txt

https://arboretum.harvard.edu/stories/exploring-the-native-range-of-kentucky-coffeetree/

Van Sambeek, J.W., Nadia E. Navarrete-Tindall, and Kenneth L. Hunt. 2007. Growth and Foliar Nitrogen Concentrations of Interplanted Native Woody Legumes and Pecan. Proceedings of the 16th Central Hardwoods Forest Conference. pp. 580-588.

Bowles, J.M. 2004. Special plant abstract for Gymnocladus dioicus (Kentucky Coffee-tree). Walpole Island Heritage Centre and Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 3 pp.

Densmore, Frances. June 1972. Menominee Music. Da Capo Press, New York, New York. 230 p

Macfarlan, Allan and Paulette. March, 1958. Handbook of American Indian Games. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, New York. 288 p.

Gurnoe, Katherine J. 1971. Indian Games. Minneapolis Public Schools, Minn. 26 p.

Day, Gordon M. The Indian as an Ecological Factor in the Northeastern Forest. Ecology, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Apr., 1953), pp. 329-346.

Any tips on seed germination?