Exploring Indigenous Norwegian Farming: Integrating Hunter-Gathering and Sustainable Practices

A rural resistance with tools for the modern era

While images of Norway in our minds are refined— from the small cities and clean streets to the untouched snowcapped mountains that make up much of its cooler climates— its history and agricultural culture offer some interesting insights into land stewardship. Because of this difficult landscape, Norway’s agriculture relied on intense management that worked with the landscape, instead of forcing conventional crop systems upon it. These intensive agricultural uses may have been at its peak as recently as 1900.1

The mountainous landscape, short summer season, and the isolating lifestyle of the country itself, which is more sparse than others by most standards, has led to some unique conditions for the local populations. It seems very likely that what evolved in western Norway bridged the gatherer economy with the beginning of the agricultural way of life. Many of these farmers were both fishermen as well as farmers.2 This was especially true of the north and they were able to continue their old-fashioned methods of farming, aimed simply at subsistence. This type of farming combined with fishing, which sometimes kept the men away for weeks or months at a time, helped the peasant community in the fishing districts’ characteristics, which in some cases have persisted right up to the present.

Now, how far back does this practice go? We know it’s been at least a few thousand years, based on written and cultural evidence, but research on pollen records as presented in the Journal of Archaeological Science in 2018 paints a much more interesting picture. This research showed evidence of forest clearing, local burning, and soil changes indicative of grazing as early as 7,000 years ago.3 What’s particularly important to keep in mind here, as well, is something we had talked about in the first piece of this substack, and that’s about the evolution of our climate— that around this same time, the ice sheets were receding from the landscape, and these were practices these people brought with them as they moved further north, which could have been for a host of different reasons.

The records, going back roughly 10,000 years to when the land first was opened up from its icy rest, show a quick succession of hazels and eventually birches, as well as first and shade-loving, water-saturated understory plants. Human activity quickly stepped in and managed the forest, clearing much of the hazel and nearly all of the firs that covered the landscape. Records show massive amounts of wood being cut and left to rot, as evidenced by the fungal record; as well as controlled burns, and an opening of the landscape. Massive increases in dung and changes in the soil composition show evidence of new animals being brought in and controlled. Now where it gets interesting is that they can use local sites to compare disturbed and undisturbed areas, which reinforces what was done by humans versus nature. Overall, the pollen record suggests that the local environment was intensively disturbed, whereas the woodland surrounding it remained largely unaffected by anthropogenic activities during that time.4

Looking to the Trees

During the long winters animals were fed primarily dried leaves and occasionally grass hay. Leaf fodder requires less sophisticated tools than hay cutting and is less dependent on periods of long warm weather for drying. The ways of doing it were passed down by word of mouth and largely not written down. It’s an ancient practice that’s been mostly lost in modern days. Lopping or Lauving was the actual process of fodder collection, either from a pollard, or from a coppice. Coppicing is the practice of cutting a tree down to the ground for it to regrow, while a pollard is a tree that’s been cut at a certain height so all the new growth comes from one spot.

Another term you’ll hear is shredding; the only difference between shredding and pollarding is that pollarding cuts the tree back to the same spot on the trunk, and shredding is the term used to cut just the side branches, which allows for the tree to get taller for future lumber use, while still providing tree hay, and allowing for more sunlight penetration to the understory, usually for grass grazing. The branches were cut with their leaves still on and were gathered into bundles and then dried by putting them in the pollards or on structures such as tripods or racks to protect them from grazing animals. The branches were dried for about 14 days and then brought inside. Sometimes, the branches would be broken down further into smaller clusters to make the branches easier to store, and sometimes the leaves themselves would be stripped and stored in sacks for feeding.

The trees they used for fodder were primarily ash, elm, birch, and willow, and the trees were generally about 15 years old when they started the pollarding process. They’d be cut in July and August and were cut again 5-7 years later. The trees were cut hard to stimulate buds near the top of the stubs, creating a candelabra shape. In the winter, trees that were felled for firewood would be stripped of twigs and bark, primarily elm and ash, and used as additional supplemental feed. Again, nothing went to waste. During harder times, they would eat the inner bark of certain trees. This practice of peeling the bark was called Skav, and the bark was then cut into small pieces, mixed with warm or cold water, and fed to cattle in the winter and spring. The rest of the wood was used as fuel.

There are a few reasons tree integration was so imperative for Norwegian farmers; with a short summer season and abrupt weather changes, focusing on annual crops was riskier than working with the trees coevolved for those conditions. Further, by utilizing trees in meadows, there is less radiation and evaporation under the tree canopy so the soil stays moist. A well-developed tree root system binds sand and gravel, preventing erosion while nutrients are drawn up from deeper soil to the surface by the roots. Traditionally, the meadows were grazed for a short period from May to early June, which prevented aggressive grass species from dominating. The sward is left for 7 weeks or so to grow until it is mown in late July. Sheep dung might be raked up after the spring grazing so it did not get in the hay. Grazing takes place again in the autumn which helps to create gaps in the sward for seedling establishment and helps promote a high flora diversity.

The cutting of the trees coupled with different management of the land around them resulted in three main types of ‘Human-induced vegetation types’, although these categories do, to some extent, blend.5 It’s worth noting that pollards have been documented in all three.

Pollard woodland (not grazed)

Wooded pastures (grazed)

Wooded meadows (mowed).

The Pollard Woodland was deciduous woodland, exploited for its fodder e.g. Lopped in summer or autumn or shredded in winter/spring every 5-7 years. For example, elm groves where each tree was lopped at several heights to maximize the amount of leafy twigs for tree fodder. These trees were shredded in spring and the sappy branches and buds were fed to the animals. The grazed Wooded pastures were usually birch groves and land with low productivity, such as shallow soils or gravel terraces. The trees had well developed root systems to help bind the soil and stop erosion. The appearance was often park-like, with scattered trees and grazing underneath. Birch groves were stable and generally regenerated from suckers. Elm groves also occurred as wooded pastures.

The Wooded Meadows were mostly meadows with pollards scattered about. The tree layer could include one or several species of trees, usually birch and ash. The ground flora tended to be patchy due to a mix of sun and shade.

Research has shown that because of the pollarding cycles and the savannah-type habitat that exists in this space where there’s such extensive variety in these types of forests, there was seven times more diversity in these human-managed forests, utilizing pollarding, grazing, and this ancient knowledge, which not only benefited the farmer and the animals that grazed these trees but also nature.6 While we have documentation of at least four thousand years in this region, we may never know how long they’ve actually been going on.

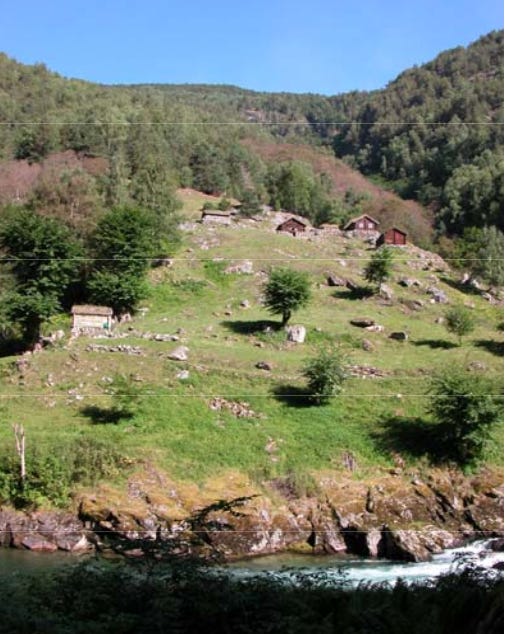

I want to talk about a historical farm that continues to operate today that gives us a good idea of how these farmers and communities operated. Havråtunet is on the Island of Osterøy, north east of Bergen, at an altitude of 60m and on the edge of the fjord. Norwegian farms were traditionally small groups of families living in small settlements or ‘cluster farms’. Havråtunet is a cluster farm that is a living museum and gives a good idea of what farming in Norway was like traditionally. Today it is funded 50% by the Government. The cluster farm of Havråunet had 60 people living in it in 1900.7 It was managed traditionally until 1960 but only the areas near the farm buildings were actively managed, while the outer fields were neglected.

The typical Scandinavian farm had an ‘infield’ where crops were grown and were close to the buildings and an ‘outfield’ which was usually rough summer grazing. At Havråtunet each farm had a one-acre plot of land where they could grow grains and roots. Mostly the people worked on their own personal plots but for the staple crop plantings and hay harvesting, they helped each other. Beyond this garden space, most other land was communal.

There’s also Grinde Farms, which is particularly interesting because they've been trying to learn some data about how this farm works compared to modern agriculture. The farm has been operating since the Bronze Age, speaking to the length of time these traditional farming practices have been in place. For example, in their pollarding practices of primarily elm and ash, they produced roughly 850 pounds of fodder for animal consumption on an acre, which is significantly less than the average hay field, which produces closer to 4,000 pounds of hay, but the land showed that the conventional grass hay production under the trees was around 5195 pounds. While that 850 pounds of fodder is cycled every 5 years, meaning you’d average about 210 a year, these organic, unsprayed pastures produce roughly 5400 pounds of fodder, about 1400 pounds more per acre than conventional farming, while using zero machinery.

The average farm holding in western Norway had six to ten cattle and calves—until recently, the small native breed vestlandskyr—twenty-five to thirty sheep or goats, and a horse or two. It took between 2,500 and 3000 bundles of leaves to keep them fed through the winter. A good family team could cut, make, and hang 50 or 60 bundles per day, taking 15 or 20 from each tree with a daily yield was about 100 pounds of ash or 200 pounds of elm over the course of two months. For fourteen days, they dried it, and then it was stored in the barns.

Before the land reforms of the nineteenth century, most farms had a cluster dwelling place, where seven or eight extended families might live together with collective ownership. In the old days, the nearby fields were divided into strips and shared or traded among the group members. Each was a private holding, some for crops and gardens, some for grazing cattle, sheep, and goats, some for hay, and some woodland, almost all of it pollarded. The subdivision of farms created small tightly packed communities of peasants, all roughly equal in social and economic status. Farmers followed the green as it spread up the hillsides in spring, then back down in autumn. Each farmer had at least two farms, and many had three or four: a main farm, a spring farm, a summer farm, and an autumn farm.

The spring farm was a way station, often on a plateau just a little up the valley, a few hundred feet higher than home. The farmer looked for a place that had grazing and where at least one field might also be mowed. The cattle and the sheep would feed in the meadows through the late spring. The spring farm was near enough home that you could come down in the evening. At the Grinde’s spring farm, they stayed overnight, milked the cows in the morning, brought the milk down, worked on the home farm for the day, and went back up to milk the cows in the evening. After the animals had gone up to the summer farm, men from the main farm would hay the spring farm meadow, storing the fodder in a stone or a wooden barn. In winter they would come up with sleds to bring the hay home.

The summer farm was different— it was higher up on the mountains and far from the primary home— often a whole day’s walk from home. The people who kept it lived there for most of the summer—from four to ten or twelve weeks, depending on the location and its microclimate. Historically, the women and girls milked the animals and made butter and cheese and the boys watched over the grazing herds. Before the end of the nineteenth century, there were an estiamted seventy thousand summer farms in Norway. By early September, they brought the animals down, often again to the farm they had used in the spring or sometimes to a separate autumn farm for two or three weeks, and then back to the main farm.

In many areas of Norway, farming was characterized by an extensive use of land held in common, partly in the shape of common ownership and partly in the form of an intricate division of territory which gave each farmer a large number of widely scattered strips and plots. The smallest in size and largest in number of such holdings were to be found in the coast and fiord districts, where the farms were extensively divided and where the areas of arable land were smallest in relation to the population.

Common ownership fostered mutual dependence and demanded mutual adjustments between users of the same sub-divided farm. Social relations of the same sort were also often prevalent between peasants on different farms which, because of natural circumstances or historical development, had certain interests in common; these interests might relate to forests, to the cutting of woodlands, or pastures, to fishing, be it in lakes or at sea, to sites for boat houses, or to roads and bridges. The variety of work inherent in subsistence farming created a basis for extended mutual help between neighbors and the need for relatively large households attached to each farmer. The high degree of economic self-sufficiency, the difficult and infrequent communication with other parishes, towns, and the outside world generally, all helped to make the household and the circle of neighbors a community of the utmost importance to every individual, who felt very much in its power.8

In the 1950s, Norway set out to record what remained of these ancient farming practices before they were lost, and studies were done to document their history. Mr. Halvard Bjorkvik, historian and philologist, summarized the research in what I think is an incredibly insightful quote, stating that:

In order to make the basic points of the Institute's investigations more easily understood by non-Norwegian readers, I will end this introduction with a discussion of the meaning of the Norwegian word and conception which in English is generally expressed by the word 'farm', and which I have occasionally expressed hitherto as 'sub-divided farm'; I might as well have called it 'complex of farms'. The fact is that all these conceptions are expressed in the one Norwegian word gard or gard (etymologically identical with English 'yard' in 'courtyard', 'churchyard' etc.). To-day, now that enclosure has taken place, this word conveys to most Norwegians a picture of one single peasant's dwelling and fields, such as it has apparently always done in most parts of Denmark and Sweden.

In Norway, in the past, this conception of the word prevailed only in the eastern parts of the country, especially in the open lowlands in south-eastern Norway and Trondelag, where the farms even before the enclosure formed individual units with houses and grounds fairly clearly separated from neighbouring farms. In the mountain districts, however, and especially in the fiord and coastal parishes in the west and north of Norway where the farms had been most extensively sub-divided, and where space was scarce, the peasants from the same sub-divided farm usually built their houses close together in a common tun (etymologically identical to 'town') and had a comprehensive and complex agrarian community.

Here the word gard continued to be used for the whole collection of lands and dwellings which was covered by the same original place-name; it was thus a unit of individual, but more or less mutually interdependent, 'farms'. In its questionnaires and instructions the Institute uses the word gard in the sense of a sub-divided or multiple farm. This is normal in many parts of the country and readily understood everywhere, even in the eastern districts, where multiple farms are not by any means unknown, and where people at least have a clear conception of the fact that a group of separate single farms can spring from one original farm the name of which the secondary farms still carry. The individual peasant's dwelling and land, in accordance with authorized Norwegian usage, are called bruk or gards-bruk ('individual holding of a farm'). No difficulty is caused by the fact that both gardsbruk and gard, according to meaning, are also used in connection with the numerous 'farms' in all parts of the country which still remain undivided and therefore constitute a single person's holding (apart from possible cottager's allotments, which were the property of the farmer and were never referred to as hard).

The Norwegian language lacks an indigenous word for the European conception of 'village' Or 'hamlet'. The Swedish by (known in many town and village names in England) has this meaning, though with many local modifications, but in Norway it has for centuries only meant 'town'. The Danish landsby (village) is used in Norwegian, but only about villages in other countries. Even as far back as our provincial laws of the Middle Ages there is no evidence to be found of any planning of settlement and field system, and there is no parallel in Norway to the detailed regulations to be found in Danish and Swedish laws.

Kussalid, another ancient farm that has been brought back to life, operates in contrast to the other two projects and paints a picture of what the future of these practices could look like. The farm has about 100 pollards and Kåre, the farmer, has developed a way of using the leaves as fodder but has adapted the traditional methods to suit modern farming. Cutting and making leaf bundles is time-consuming and the bulky dried leaves need lots of space to store. Kåre cuts branches from the trees and shreds them in a shredding machine. The material is then spread out on the concrete apron of the barn and dried. Harvesting of the leaves using this modern method provided the equivalent of 537 bundles of leaves harvested in a day; roughly 5 times quicker than the traditional method.

In this practice, we can see the longstanding history of the indigenous people being a functional part of the landscape— it wasn’t something that was manipulated for singular use, but for the collective good of all nature. Unfortunately, a lot of this tradition has been lost to globalization, but folks are looking to keep these traditions alive, and in doing so, we keep ourselves connected with our history and with the ecology.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 15-page chapter, of (so far) an 1193-page book with 831 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #28 of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Logan, W. B. (2020). Sprout lands: Tending the Endless Gift of trees. W.W. Norton & Company.

Professor Andreas Holmsen (1956) The old Norwegian peasant community: Investigations undertaken by the institute for comparative research in human culture, Oslo, Scandinavian Economic History Review, 4:1, 17-32, DOI: 10.1080/03585522.1956.10411481

Austad, I., Hauge, L., Helle, T., Skogen, A., & Timberlid, A. (1991). Human-influenced vegetation types and landscape elements in the cultural landscapes of Inner Sogn, Western Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 45(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291959108621979

Bele, B., & Norderhaug, A. (2013). Traditional land use of the Boreal Forest Landscape: Examples from Lierne, nord-trøndelag, Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 67(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2012.760002

Bostwick Bjerck, L. G. (1988). Remodelling the neolithic in southern Norway: Another attack on a traditional problem. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 21(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.1988.9965464

Solheim, Steinar & Wieckowska-Lüth, Magda & Schülke, Almut & Kirleis, Wiebke. (2018). Towards a refined understanding of the use of coastal zones in the Mesolithic: New investigations on human–environment interactions in Telemark, southeastern Norway. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 17. 839-851. 10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.12.045.

Catorci, Andrea & Vitanzi, Alessandra & Tardella, Federico & Hršak, V.. (2011). Regeneration of Ostrya carpinifolia scop. forest after coppicing: Modelling of changes in species diversity and composition. Polish Journal of Ecology. 59. 483-494.

So interesting, thank you for doing so much work to bring this article to us. I've been interested in using tree fodder/hay for feeding ponies and this is very useful historical info.

Wow, very interesting. Thank you.