Taming the Wild: Training Your Fruit Trees for Maximum Yield

The ubiquitous fruit of North America- apples- is everywhere for a reason, and the reason is pleasin'. We also talk about some other fruit, for science!

When I was a kid, my grandfather had a pair of apple trees that stretched across the entire back deck and they seemed endless. The apples were large and red and were mostly for the neighbor’s chickens, who pecked out the bugs with glee. My grandfather was a phenomenal gardener, and had spent his entire life in Italy as a subsistence farmer while also managing a few acres of ancient vineyard and olive groves, but he never quite got a handle on yankee fruits. His pride and joy were the plum trees nested in the far reaches of the small lot behind the annual garden. What he lacked in apple knowledge he made up for in stone fruit.

I visited the land he had tended for decades, which had been in our family for generations on my honeymoon. Today, his brother’s son manages the vineyard, although his children have no interest in keeping the vineyard going. The trees and vines feel infinite and the weight of history is incomparable. The thought of the land being left untended is heartbreaking but inevitable; poor pricing and few opportunities in rural southern Italy means there’s little hope for most in these small towns. The relay race of human knowledge once again drops a baton, and a little more knowledge will be lost.

When we talk about stewardship, particularly in the arena of fruit, the idea of learning to grow is fundamentally individualistic— the fact you’re reading this is testament to that fact. Most folks are familiar with growing fruit based on what they get at the big box store. They see an apple tree that says ‘granny smith’ for $40, they buy it, plant it in the ground, wait a few years, get 10 apples which they don’t treat in any way, because at that point, what’s the difference between the apples at the the grocery store anyway? Those apples ultimately get bugs in them and drop from the tree early (or are completely inedible), and then the next year those same people spray the everloving Jesus out of it because god damn you’ve had this tree for 5 years and you want to get 1 fucking apple out of it, but now you’re like $200 dollars into 20 pounds of apples, and the branches start getting too high to reach so you just say ‘screw it’ and the tree eventually dies or gets cut down. It’s okay, we’ve all been there. We are trained how to take care of plants by our grasses, and we don’t do anything remotely normal when it comes to taking care of that, so how would we have the skills for fruit trees?

Now, on the other side of things, some folks will have this apple from the store or the farmers market or wherever and think, god damn this is the best fucking apple i’ve ever had in my life, and they go and save the seeds. They think, I’m gonna plant this seed and I’m going to have the best apples anyone has ever known and everyone’s gonna be jealous about my apple pie. Unfortunately, fruit trees do not grow true from seed. This means that if you were to plant six seeds from a Honeycrisp apple and grew them into trees until they produced fruit, you would get six completely different fruit, and they may not look or taste anything like Honeycrisp. This is also true for pears and stone fruits. To preserve the unique qualities of the Honeycrisp (or any cultivar), a fruit tree must be vegetatively propagated by grafting together two parts: The Cultivar - top part of the tree, which is a clone of the desired cultivar (e.g., Honeycrisp), and the Rootstock - the bottom part of the tree, which consists of the root system.

Now, what is a cultivar? The term cultivar is short for cultivated variety. Cultivars of tree fruit are vegetatively propagated. The root system and the above-ground portion are joined by grafting. The portion of the tree above the graft is called the scion. To produce the scion, portions of wood from an existing tree are used to create a new, genetically identical tree. For example, when you purchase a Honeycrisp apple, the tree that fruit came from was once a scion from another Honeycrisp apple tree that was once a scion from another Honeycrisp apple tree and so on until the original tree that was planted by seed and produced the original Honeycrisp. Cool, right?

This ensures the apples produced on your tree will be the same exact Honeycrisp. At grocery stores and farmers markets, cultivars are commonly called varieties. What you might find sometimes, if you go to— ahem, HOME DEPOT, they don’t do a good job of listing the varieties, because they are not a part of the fruit tree’s latin name. Not that I’m annoyed or anything about it, especially when their generic “red” apple trees are on clearance. Anyways.

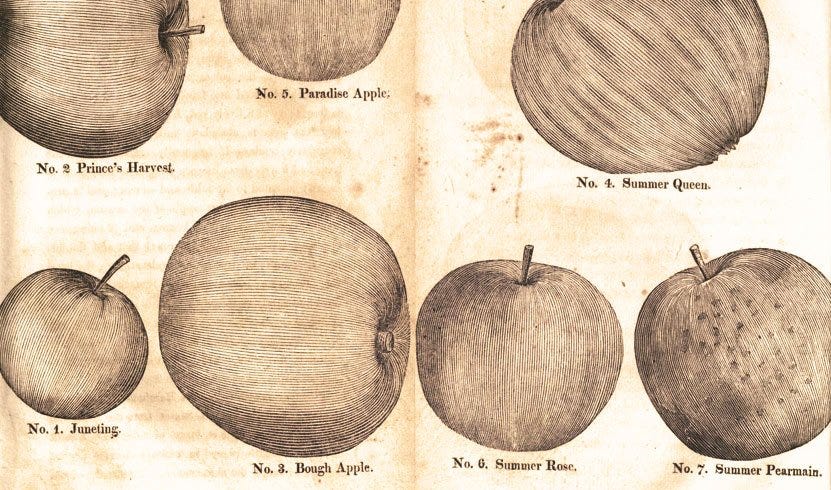

A sport, or strain, is a subtype of a cultivar that differs from the original cultivar in a specific characteristic. Yet, is similar to the parent cultivar in all other respects. Sports boast characteristics like early maturity or enhanced color. Sports often originate when an observant grower discovers a naturally-occurring limb mutation and propagates it. Some varieties have many strains; for example, approximately 250 different strains of Delicious have been described and cultivated.1

A common strain difference a new fruit grower should be familiar with is spur strains versus non-spur strains. Spur-type growth is more compact since fruit spurs and leaf buds are closer than those on non-spur trees. Spurs are short, slow growing stems that can bear leaves, flowers and fruit. On spur types, two-year-old wood will usually form fruit buds rather than develop side shoots. As a general rule of thumb, spur strains of a given variety will result in trees only about 60-70% as large as the non-spur types of that variety.

Every fruit type has its own specific disease challenges, and since something like 40% of the fruit trees grown on non-commercial properties are apples, they’ll get a little more attention today. Apple scab is the biggest apple disease concern in the Eastern United States. Many scab-resistant cultivars have recently been released as a result of breeding programs in the U.S. and elsewhere. They were developed primarily for resistance to apple scab, but some are also resistant to cedar apple rust, powdery mildew, and fire blight. Disease resistance does not mean total freedom from pesticides, since none of these cultivars are immune to insect damage or summer diseases like sooty blotch or flyspeck.

So I know i just dumped a bunch of different diseases and issues on you without going through what they are. As a rule of thumb, you learn diseases as you deal with them— that’s really the only way. Experience is your best educator here, and when you see something that doesn’t look right on your fruit tree, you’re never going to remember what you read two years ago. Once you live it, you’ll know it.

Cider Time

Now in my own house, cider is a primary concern for apple use— both fresh and hard varieties. Hard cider apples have many characteristics that differ from fresh market cultivars. There are four categories of cider apples: bittersharps, bittersweets, sharps, and sweets. The different categories depend on the concentration of tannins and acids within the fruit.

Cider apples can be tart, tannic, or generally inedible in their natural form. And, if you’re curious about why most of old, heirloom apples don’t taste very good, it’s because apples are really good at fermenting and storing as a fermented drink so that’s how we primarily consumed apples.2 While these characteristics might not get your kids happy to eat fruit, they provide the complexity and depth to make the best ciders in the world. Conversely, making cider from the apples in the grocery store makes as much sense as sitting down and eating a bunch of tannic apples.

Most of the apples you are familiar with fall into the 'sweets' category. The sheer availability and low cost of this fruit makes it ideal for providing the bulk of a cider's fermentable sugar and its apple-y aromas. When blending fruit for cider, sweets can provide up to 50% of the juice for a batch and enough sugar to ferment 6% to 9% ABV cider. Common varieties include: Golden Delicious, Johngold, Macoun, Gala, Fuji, Braeburn, and Honeycrisp.

Sharps are the necessary counterweight to the sweets. Filled with the classic puckering acidity we associate with crabapples, sharp apples provide tartness to a cider. In some cases, sharps can be very juicy, but often, they are harder and mealier than sweet apples. Sharps can make up anywhere from 25% to 33% of a cider's juice. The acidity in sharp apples serves two purposes for the cider maker. The first is balancing the sweetness, the other benefit is that the acidity inhibits bacterial growth and helps to prevent spoilage. While the alcohol is an important part of its storability, the acidity from these sharp apples are what makes cider so good at storing.

The Granny Smith is America's ubiquitous sharp apple, and these apples are used by most large and medium-sized American producers as a source of acid. Heirloom varieties such as the Rhode Island Greening, and my personal favorite Calville Blanc, are both great options for cider making and apple cider vinegar.

If there is one style of apple prized above all others by American cider makers, it's the bittersweet apple. Often called "spitters," these apples are low in acid, high in tannin, and are part of the classic English cider flavor profile. At first bite, most would consider bittersweet fruit inedible. The high tannins give you the same dryness you get from a red wide, and can leave your teeth feeling fuzzy and rancid.

Chances are, you’ll have never heard of any bittersweet apple varieties unless you’re really into ciders, because they won’t be found on any supermarket shelves. Michelin, Dabinett, Brown Snout, and Bulmer’s Norman are some of the more common varietals available if you want to order some trees online.

General Management

While cider is a huge part of why we grow tons of fruit (because otherwise most of it will go to waste), it’s important to start thinking about the bigger-picture questions— what do you intend to use the fruit for (other than ciders)? Some varieties taste great for eating fresh, while other cultivars are particularly good for baking.

Some cultivars are more disease-resistant than others. This may be important, for example, if your site is surrounded by abandoned apple trees that may be harboring diseases. Cultivars vary in bloom timing. Many cultivars won’t produce a lot of fruit unless they are pollinated by different cultivar, which means you’ll need to figure out which cultivars bloom at the same time. This also means that many cultivars bloom at different times, which also means they fruit at different times. For example, peaches can be picked from early July up until early October.

Depending on your property size, you’ll want to think about how to maximize your harvest season for your fruits and incorporate the longest storing options, as well as making sure that blooms for pollinators line up. Lastly, keep in mind what the apples are for. It seems like a complicated web to narrow down your fruit tree search, so first I’ll recommend creating a spreadsheet with each tree you want, the bloom dates by month, harvest dates by month, storage time, and what use the trees have. When you create a list of 15-20 trees, you’ll see where they start to overlap and be able to pair down your options.

I currently have 10 apple trees on my property, almost all of which are heirloom, which lets me harvest from August to late October and proper storage will let me eat them all the way to April. My primary focuses are on sweet fruit trees, 2 for pies and desserts, and then a few that we are using primarily for ciders which I listed above. While 10 trees may seem like a lot, they are mixes of dwarfs and trees that will be pruned to stay dwarf sized— these are trees that stay under 10 feet tall and 10 feet wide. What that means is that in an area that is 40 feet wide by 20 feet deep, I’m able to have 10 fruit trees producing basically all of my apples for 9 months, and my kids love apples. And my partner loves cider.

It’s also important to keep in mind how much fruit your trees will push out. A typical dwarf apple tree can produce at full maturity around 200 pounds of fruit, while a semi-dwarf will pump out up to 400 pounds of fruit, and a standard tree can easily produce over 400 pounds of fruit if managed properly.3 Of course, keep in mind that you’ll never get all of those apples, ever. And how many apples are we actually talking about, here? A rule of thumb is that a pound is 3 apples. If you’re planting, say, 10 standard apple trees because you need both pollinators and a few different varieties for specific uses our because you enjoy them, it’s important to think about what that really means in terms of what you’re going to do with all of that production. Cider and compost.

So I’ve been Told Fruits other than Apples Exist

Additionally, it’s important to tie in various fruit trees— pears, plums, peaches, nectarines, persimmons, pawpaws, mulberries, figs, cherries, serviceberries, quinces, and so on— in order to not only provide diversity if you’re thinking about your community’s consumption, but to extend harvesting seasons from July through November. Further, having this variety limits catastrophic loss from disease or bugs that could potentially wipe out all of one fruit variety. As climate change continues to ravage our seasons, it’s more and more common for extra late frosts to kill off the first blooms of the season, and extra early winter frosts to destroy the last crop of the year, so it pays to have some variety to cover your needs.

I wanted to cover a couple of specific nuances about each fruit that will be helpful in guiding what research you might do to expand what you’re looking to grow. Starting with pears— there are two types of pears— European and Asian. Asian pears aren’t common in grocery stores, and European pears are not eaten ripe off of the tree— you’ll want to pick them when mature, but not ripe, and cold store them for a few weeks. European and Asian pears generally bloom at different times and fruit at different times, extending your season, but also keep in mind they can’t really pollinate each other because of this difference. With peaches and nectarines, which are actually in the same family and share most traits, you’ll generally hear them defined by freestone or clingstone. What they are referring to is the pit— they are stone fruits, meaning they have a large seed in each fruit, and freestone and clingstone refer specifically to whether or not the fruit clings to that stone pit in the center of the fruit. You’ll also hear the fruits referred to as yellow versus white fleshed. Generally, white-fleshed are sweeter flavored, but yellow peaches and nectarines are able to store for a short period of time, whereas the white-fleshed aren’t able to store for any meaningful period.

Cherries are an often-forgotten fruit when it comes to fruiting trees. Most folks know cherries as sweet or tart cherries, and that’s a pretty good place to start. The general rule, as you’re probably starting to realize, is the more sweet the fruit is, the less well it stores— and that applies to cherries too. Sweet cherries are a challenge to grow and are very susceptible to, well, everything, which is a large reason most folks don’t grow them.

Much like pears, plums have both European and Asian varieties. And, of course, there’s the American varieties, which will get their own separate piece at another date. The short answer is to grow them if you can for fresh eating. Generally speaking, European plums are good for canning and dried fruits, while asian varieties are the ones you’ll eat fresh. And, again, they won’t bloom at the same time so you’ll need 2 of each variety, and they can’t be the same cultivar. Plums are some of the earliest fruiting trees, so despite needing quite a few trees, it’s worth having them around. Plus, I mean, who doesn’t love plums.

The last fruit I want to touch on quickly are persimmons— which have American & Asian varieties. Most persimmons are self-pollinating, and are almost always the last fruit harvested— some fruit will hang onto the tree into December. For Most folks, if you’ve eaten a persimmon, it has been an Asian variety, as the breeding programs have developed fantastic cultivars that are seedless and offer complex, sweet flavor. American varieties generally have to soften up to the point of mush to be edible and often harbor hard seeds. That doesn’t make them any less tasty, but because of the texture can be an acquired taste.

Rootstock

Now, reversing back to the earlier part of the conversation about trees, folks generally don’t grow trees from seed since they won’t be true to the variety of fruit that the seed came from, due to pollination. If we want to keep the unique qualities of a cultivar, we have to propagate trees by grafting. As we talked about, the top of the tree is a clone of the desired cultivar, called the scion. The bottom part of the tree consists of the root system - the “rootstock". Some rootstocks reduce the size of the trees growing on them; these are known as "dwarfing rootstocks." Rootstocks can also provide many other horticultural benefits to the fruit grower, like conferring disease resistance.

As you plan your orchard, you’ll have some decisions to make as you weigh the pros and cons of various rootstocks. For instance, if your soil that is full of clay, you will want to choose a rootstock that is better adapted to that soil type, even if it has some other traits that are less desirable than some of the other rootstocks available.

A rootstock is a fruit tree variety that was specifically grown for its root system. Depending on how they’re produced, rootstocks are known as either seedling rootstocks or clonal rootstocks. To grow seedling rootstocks, seeds from processing fruit, (usually Red Delicious for apple, Bartlett for pear, Lovell and Halford for peach) are planted and grown, and then a scion of a cultivar is grafted to the top to produce a new tree. There are also clonally propagated rootstocks. Similar to how apple cultivars like Honeycrisp and Fuji have been selected for high fruit quality, some rootstocks have been selected for various attributes, including size control, cold hardiness, and disease resistance. To preserve these specific traits, these rootstocks are produced through vegetative propagation. If you look at a fruit tree, you can clearly see where the scion and rootstock were joined together. There will generally be a bulge at this area, which we refer to as the graft union. When we talk about rootstocks, it’s important to know that there are only a few fruit trees that this is an option for—primarily apple, pear, peach, cherry, plum, and apricots.

Is Bigger Better?

Other than making trees more accessible to folk switch smaller pieces of land, why would size regulation be good for folks even with larger spaces? Obviously, smaller trees are easier to maintain, but they also allow more light and air through the canopy, reducing fungus and mold issues, increasing fruit quality. Additional light not only helps regulate those fungal issues, but also increases fruit size and allows for under canopy crops such as berries and other perennials.

If you are looking to keep smaller trees and there aren’t dwarf cultivars, there are ways to manage your trees to treat them as dwarfs. The first and most obvious is training and trimming. There are a few basic rules when it comes to trimming trees— you want to trim suckers and branches that will cross with one another with the goal of thinning your tree for air and light passage. Try not to cut randomly on a branch, but take it back to a node— the place where a leaf or another branch originates.

The general rule is that the more horizontal a branch is, the more fruit will grow, and fruit production takes energy away from tree growth. This is one reason why you want to cut suckers from your fruit trees— they generally go directly vertical and suck away a lot of energy while also likely never carrying much fruit. Espaliered trees, much like grape vines we see at vineyards, are a great way to manage and mitigate large growth in trees while also maximizing fruit production. This process involves usually using a line to tie branches to going horizontally, making the tree look almost like a fence picket. Further, by cutting off the main stem of the tree, you can redirect that energy outward towards the branches, which, if they’re being managed, will reduce tree growth vertically.

Girdling is another option for managing your tree growth, but it does slightly reduce your fruit production. Girdling is cutting into the trunk of the tree enough to reduce nutrient and water flow in the tree but not enough to kill the tree.

Site location can also be a significant factor when trying to manage tree growth— choosing poor soil locations or cooler places in your fields can slow growth. Gulleys tend to be cooler, but also are nutrient accumulators, as you might remember from the forest ecology episode, so each site must be assessed for this specific use. This is also where knowledge of your soil biology is crucial, as you can target specific places for specific tree management practices.

There’s also a traditional farming method still practiced in much of the west coast called deficit irrigation, which is essentially limiting water intake as much as possible without damaging the plant to reduce its growth. Additionally, by trying to reduce nitrogen availability, which is tricky, but can be done using other nitrogen demanding crops around the fruit trees, helps reduce shoot growth. Both of these practices can be hard not only because measurement when not using nutrients is more art than science, but the effect may reduce fruiting, while keeping growth the same, or it may not be evident until the following year. You’re basically trying to give the tree so little resources it doesn’t grow, but not so much that it drops fruit early in order to keep itself alive.

Tree Competition

This concept brings me to a related idea of between-tree competition, which is exactly what it sounds like— using other crops between your trees to introduce competition for the available nutrients.

Between tree competition is a form of orchard floor management, which is how we control what grows below the canopy of our fruit trees. While we may enjoy the vision of fruit trees rising up from a thick grass field, weeds and grass are often direct competition for the same nutrients. If you’re looking to manage your tree size, by allowing some grass and weed growth going into the fall season, you can mitigate some growth of your trees. However, whether or not your goal is to limit tree growth, it is ideal for the tree’s health to control weed growth around young trees and 4-6 weeks after bloom.

However, I want to circle back to the training methods, because these will by far be the most impactful decisions you make to your fruit trees when it comes to fruit production and quality. Simply put, the natural growth habit of a fruit tree is not always in line with what we want to get out of the tree in our orchard. For example, unpruned apple trees may grow very tall, producing branches with very narrow branch angles that may grow as tall as the main trunk of the tree. This would make the tree lose its dominant leader, which would lead to a lot of vegetative growth with little fruit production. By understanding the growth habits of these trees, we can make little changes to which branches remain and how easily they access nutrients in order to maximize production for our own benefit.

The best way to think about this is to remember that trees evolve to grow in specific conditions, and we’re not mimicking those conditions entirely, because we are trying to increase production. To do that, we need to help the tree take advantage of the “unnatural” conditions that they haven’t evolved for, but have the capacity to utilize.

Tree Anatomy

This brings us to branch morphology and growth habits. There’s a few terms I want to clarify, otherwise it might get a little confusing as we talk about some of this stuff. The first term is leader, which refers to the trunk of the tree all the way to the upper point of the trunk. While I’m sure everyone knows what a branch or a limb is, you may not be familiar with shoots or laterals, which are the sections of growth off of the branches—the smaller branches off of branches are called shoots. Apples, sweet cherries, and pears, all generally have 1 central trunk— or, leader, while peaches, tart cherries, and plums generally are shaped more like an open vase without a dominant leader. I find that Asian persimmons do well vase-shaped, while American persimmons do better with a central trunk. Now, if you’re looking at a branch, you’ll have nodes— where leaves and other shoots erupt from, and internodes— the space in between. The last thing you’ll have emerge from a node is spurs, which are spots where fruits are formed on apples, pears, and cherries. Not all trees produce spurs, though, but these three are the most common.

Now that we know what we’re looking at as we consider how to train our fruit trees for yield, let’s talk about branch organization.We talked a few minutes ago about how more fruit produces on horizontal branches, but more specifically, at between 40 and 60 degrees is where we have the best match of growth and fruit production. Our goal is to help continue to grow our fruit trees while also helping provide fruit for us now. Early on in growing fruit trees, it is recommended to remove flower buds in the spring to help the tree focus on growing larger, allowing for bigger harvests in following years.

Buds are often found in two places— at the end of a branch, where they’re called terminal buds, or on the sides of branches where they’re called lateral buds. You can also have vegetative buds and flowering buds. For our apple and pear trees, generally the lateral buds will be leaves, while the terminal buds formed on short, stocky shoots—these are those spurs we had talked about earlier. Fruit generally produces on two year old spurs for apple and pear fruits, while fruit will produce on one year old spurs for peach trees. Cherries and plums, on the other hand, will produce fruit on both one and 2 year old spurs.

Ok, so with that, we understand how tree size is managed, the parts to fruit trees, how branches and shoots impact fruit production, and how fruit trees produce fruit. The final area of focus on fruit productivity is around light access for our tree. The general rule is that the higher the amount of light, the higher our fruit yield will be. So what we want to do is maximize our leaf area index, a term used to define the amount of leaf area in relation to the amount of ground area. To get the best benefit of our trees, we want to capture 60-70% of the sunlight hitting the ground with our trees. To get red fruit color on our apples, for example, the fruits need 70% exposure to sunlight. For good fruit size, we need at least 50% sunlight. For good flower development for the next year, we need at least 30%. This is also important to think about when you start hearing people talk about fruit tree guilds, and suddenly the science behind certain ideas will make less sense. We’ll get there another time.

When we think of maximizing our leaf area index, your first thought might be to let our tree get as large as possible, because that would be increased exposure to sunlight. However, while the tops of the tree may get all of that exposure, the middle and bottom of the tree would not, making the most delicious apples only available at the top of our tree. By keeping our trees smaller, we are able to limit the impacts of the leaves’ filtration on the harvest of the most accessible fruits at the bottom of the tree. Further, we are able to maximize our fruit tree production by orienting our fruit tree fields north to south, maximizing sun exposure and limiting the extremes of sun exposure.

With all this information, you might be thinking that it makes the most sense to densely plant dwarf trees and trying to make their branches as lateral as possible to maximize fruit production while increasing light exposure. And that is a great way to set up a small collection of fruit trees, but it’s worth mentioning a few things— trees on dwarf rootstocks generally have shorter lifespans— less than 50 years— and if you’re growing them in some kind of trained or heavily managed system, they do require more labor hours to manage them. From a long-term sustainability perspective, this likely doesn’t make a lot of sense. If you’re looking to get bigger trees with less management, it’s also important to remember that means you’ll likely have a lot of space for a number of years in between those trees that you could use for other crops, and fruit may not come for several years. For everyone, that planning decision is personal. There’s a lot of folks out there who use asparagus and other perennials between tree rows to maximize production before fruit or nut trees are ready to be harvest, or run various livestock through, which is also a great way to add biomass to the soil.

Now if you’re considering going the route of the low-maintenance, larger tree system, you’ll want to grow your apples, pears, and American persimmons in one of two ways. In what’s called a 3-tier system, your trees will want to have that central leader— traditional trunk— that we always imagine. Competing branches that try to grow vertically are either cut or trained downwards, and the tree will keep that Christmas tree-like shape. This shape maximizes light access and limits fruiting at the uppermost part of the tree, making fruit accessible for you and saving you a lot of headache. Now, if you’ve ever tried growing a fruit tree, almost none have that shape naturally. To promote branching, heading— that is, cutting the central leader— is done every year, leading to extensive new branching, and since the lower branches start growing first, they will be larger than the others. You’ll eventually end up with three tiers-- the very large, long lower branches, the medium sized branches in the middle, and very short, stubby branches at the top.

Your second option is using the french axis system— invented by the, you guessed it, french. If you’ve ever been apple picking at a newer orchard, and the trees run in tight rows with gaps about 5 feet between the rows, then you’ve seen it before. The trees are tied to a pole and capped at 10 to 15 feet, and their branches are guided to grow along the row, although not in such a strict pattern as a traditional espaliered systems like what we see with grape vines in a vineyard. Heavy branch trimming maintains the system and size and by using renewal cuts, which is cutting back branches to promote new growth and new fruiting spurs in order to maintain the tree size.

Stone fruit, such as peaches and plums, are usually trained to an open center system. Some growers also use a V system. In an open center system, the basic tree form consists of three to four main scaffolds, or primary branches that replace the main central leader. The scaffolds have secondary and tertiary branches that bear fruit on healthy one-year-old wood. Training focuses on shaping the tree to minimize the shading of fruit shoots. The ultimate height of a peach tree is determined by the selection of the main scaffolds— the new main branches. When you plant them, you'll want to head your trees to 20 to 24 inches above the soil. Then, once trees begin to fill their space, maintain a tree height of eight to 10 feet tall by cutting back scaffold limbs.

Now, I can’t really cover all the different fruit types here, so I wanted to hit the more popular ones, but most fruit trees will follow either of these or a modified version of one. Logistically speaking, if you’re planting, say, 15 apple trees, one thing I would recommend is planting them according to harvest date, and I say that for a few reasons. The first is that by planting trees that harvest at the same time, they’ll likely cross pollinate and help maximize your yield. Even trees that are self-pollinating benefit from cross-pollination if possible. The second is that when harvesting, it will be easier to keep track of which trees are ready to harvest. Assuming that you’re interested in eating more than one fruit that you’ve grown yourself, you’re likely going to be planting a lot of different things with different harvesting times, and whatever you can do to help organize the process will make your life a lot easier.

At this point, we’ve gotten a pretty decent primer of what goes into the tree selection and tree training process of your fruit trees. We can start to narrow down the trees we want for each fruit, plan out our spacing for our trees, how we are going to train them, and what is the best process for harvesting and ultimately maximizing both our yield and duration of season to have fresh fruit.

Like I said earlier, I can have fruit from my own, very small orchard, for 9 months of the year, with proper storage. My current ‘conventional’ fruit tree area is roughly around 80 feet by 100 feet— it’s not particularly large, by any stretch of the imagination. I have apples, pears, peaches, plums, nectarines, persimmons, mulberries, pawpaws, and fig tree, and they are still increasing in yield every year.

Creating sustainable systems doesn’t need to be high-tech, complex, or energy intensive, but rather well-thought out and organized by aligning our goals with nature. There’s no reason all of the fruit we eat can’t be grown in our neighborhoods, or at least within a short radius. In 1900, when New York City had 3.4 million residents, almost all of the food eaten within the city limits was grown within the surrounding 7 miles. It was done in the past and we can do it again. We have better research, resources, and a new need to find ways to decentralize our food systems and create community-based, resilient systems.

I’m not going to pretend the material in these info episodes isn’t dense— the goal isn’t that you listen to a 40 minute episode and now you’re ready to go start an orchard. Hopefully, though, you feel like you’ve got your bearings on the subject matter, and you kind of know where to start looking for the information you don’t know.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 26 page chapter, of (so far) a 157 page book with 75 sources, you can support our work a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content, the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can subscribe on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

https://extension.umd.edu/resource/growing-apple-trees-home-garden

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ancient-origins-apple-cider-180960662/

Phillips, M. (2012). The holistic orchard: Tree fruits and berries the biological way. Chelsea Green.

Great article!

Love this format of information sharing. The pruning diagram was especially helpful !