A Look at Treatment-Free, Scientific Beekeeping

Treatment-free beekeeping and following the biological systems which have made honeybees thrive

Today, we’re talking about the controversial concept of natural beekeeping. The reason we waited until the last episode to talk about this is that now that we have discussed all of these different pieces of beekeeping; the hives, the workers, queens, drones, and even the varroa, we can put it all together and apply some critical thinking to beekeeping.

If you’ve taken a beekeeping course with your local association, you’ve probably noticed that despite the fact that they cover a TON of stuff, there probably hasn’t been as much overlap with what we’ve covered in 15 or so articles as you’d expect. And that’s because they’ve taught beekeeping and bee health from the perspective of how to keep that colony, the one you’re getting for the first time, alive and healthy as long as possible. And there’s a very large difference between that and doing what’s best for the species or for our ecosystems.

We have deviated pretty far from how bees were managed only just a generation or two ago because of chemical applications and the introduction of varroa, and while we could discuss the benefits of modern chemical treatments with high overwinter losses because that increases honey production, we won’t. We haven’t talked about foulbrood or feeding, although we will a little bit today, but the whole point here is that things have been basically getting worse as a whole for decades, and chemicals are not a solution, they’re a bandaid at best. This is not a radical position; any beekeeper who has been around for a few decades will tell you that things have been getting worse for a long, long time.

So let’s talk about treatment-free beekeeping. Some folks call it natural beekeeping, but I’m not a huge fan of the term. In practice, it’s not really accurate because Natural is such a loaded term and I think can sound super crunchy, which is fine, but we’re not ignoring science in favor of what nature does, but instead looking at the longer-term viability of beekeeping, which is often ignored in the name of the infinite new products which researchers will develop just in time as another product no longer works. Part of the reason treatment-free has been cast aside as a pipedream at best and dangerous for other beekeepers at worst is that it’s often conflated with disease, and disease travels throughout beehives in an area fairly easily. So, it’s not really okay in many beekeeping circles to call yourself a natural beekeeper, although treatment-free isn’t going to earn you a lot of points with your local beekeepers’ association.

There are two major areas that differ between modern & treatment-free methods. The first is obvious; not treating bees for disease. This also means using hives that reduce the risk of needing treatment, and we’ve covered that a bit in the Topbar & Langstroth pieces. But as we said, there are folks with success using a diversity of hives. The second area is around feeding bees; modern beekeeping starts the season with a boatload of bee sugar.

It’s really just basically simple syrup with white sugar. The idea is to provide bees with food when their honey stores are low, particularly new colonies. A typical hive will go through 40 pounds or so of bee sugar in the spring to build out the comb and to get calories, which is particularly important with a new hive that arrives in cool climates when they’re not native to the region.

Feeding only honey or just taking less honey from a hive is really the ideal situation. But doing this gets complicated if we don’t plan accordingly. So let’s start with winter-time. While people assume bees hibernate, they don’t actually hibernate. The core of the hive has to stay at least 68 degrees, and closer to 95 in early spring when the first brood of the year begins to appear. Bees obtain the energy needed for heating by consuming the honey located directly above the cluster. In the process, the cluster moves gradually upward at a rate of approximately one millimeter every 24 hours.

So the bees are less able to use the honey stored in the outer combs. They can move side to side a bit but it’s more difficult. It is of more use in the spring when the weather outside grows warm and the cluster breaks up. As beekeepers, then, if we have bees that have been in our climate for some time, they’ve adapted to the temperatures and know how much to store; we don’t need to do anything but give them room. This also means we can take the honey stored to the side in a Topbar hive confidently knowing the bees should be alright.

And it’s not this cut and dry, of course; bees are living things and often do things we don’t expect. What is cool though is that this ten-inch cluster manages to maneuver around the frames in the hive, while maintaining its shape. For people who need numbers, at least 50 pounds of honey should be left for a large colony for the winter. It will consume around 30 pounds, leaving 20 pounds in reserves, without which the bees can get anxious.1

Now, not all honey is created equal. Honey gathered during the main honey flow— typically in June/July— is best suited for use during wintering. During the dearth period, late summer, when the flowers are starting to die off, bees will make honeydew honey that could lead to their deaths during winter. Honeydew honey is an emergency pollen alternative. Phloem sap-feeding insects excrete honeydew, the key component of honeydew honey. Honeydew is basically the sugar-filled poop of other bugs. But here’s the thing, if the phloem sap of the host trees has a certain makeup, the honeymaking process produces what are called oligosaccharides such as melezitose. Melezitose-rich honeydew honey is a major issue for beekeepers; it crystallizes and can be poisonous for bees.2

When we talked about honeybees versus native pollinators, it didn’t sound like access to food was really the problem, but there’s this dearth period where it is. Typically, honeydew is predominantly used by mosquitos, wasps, and some stingless honeybees— for example, there’s only been a handful of documented examples of bumblebees harvesting honeydew, and there doesn’t seem to be a lot of evidence at this point that there have been any negative impacts from honeybees during the dearth season.3 Tthe point is that honeybees ready their winter reserves ahead of time, at the peak of summer— a fact exploited by industrial beekeepers as they add and later remove a super. During the winter, the bees are unable to chew a hole through the comb, move honey, or seal any gaps that appear with propolis. All of these things must be done ahead of time— which our method of beekeeping explicitly makes nearly impossible.

Honeybees that haven’t been bred and have some resiliency have shown some of their ancestral knowledge around this, with a tendency to store reserves in the upper portion of its nest combs first; and only when sufficient reserves have been set aside for winter do they move on to fill the combs to the immediate right and left of the nest, and then those farther away. Unsurprisingly, the farther south the bee originates, the less pronounced this instinct is.

Localizing Your Honeybee

We’ve talked repeatedly about the bees knowing best, and a key point of treatment-free beekeeping is just that, specifically the bees you’re working with in particular. How local of a bee can you work with? This is difficult here in the US because the last time we had a native honeybee was 14 million years ago, according to evidence in Nevada.4 That honeybee didn’t look too much like the current options today, and your best bet, if you can get your hands on one, would be to collect a bunch of swarms, and hopefully some of them are from a few generations in your region.

If bees swarmed, they’ve been in the area for a bit, hopefully, a few years at least, and they’re strong enough bees to have swarmed, so with a little bit of luck, they’d be a significant upgrade to a traditional bee package and have proven to have higher rates of survival in comparison.5 Trust the bees. Don’t bother the bees unless it’s extremely necessary. I do two major annual inspections; spring and fall, where I actually get inside the hive and look at the comb and so on. Otherwise, I don’t bother them, don’t move them, don’t treat them. If a colony dies, that’s the way it goes. Keeping honeybees alive to pass on poor genetics doesn’t help the long-term viability of honeybees and allows them to continue sharing diseases with our native bees, which are struggling enough as it is.

In an interview with Dr. John Kefuss, we talk a bit about bond testing and soft bond testing, which are basically ways to either squeeze the bees by forcing them to survive or by reducing chemical applications or removing feeding or something basically, with the goal of forcing the evolutionary bottleneck through a shorter period.6 This has been successful for him and many other beekeepers and allows bees to slowly adjust to becoming more resilient instead of being fully hands-off. You can read more about this process here.

Beekeeping Cycles

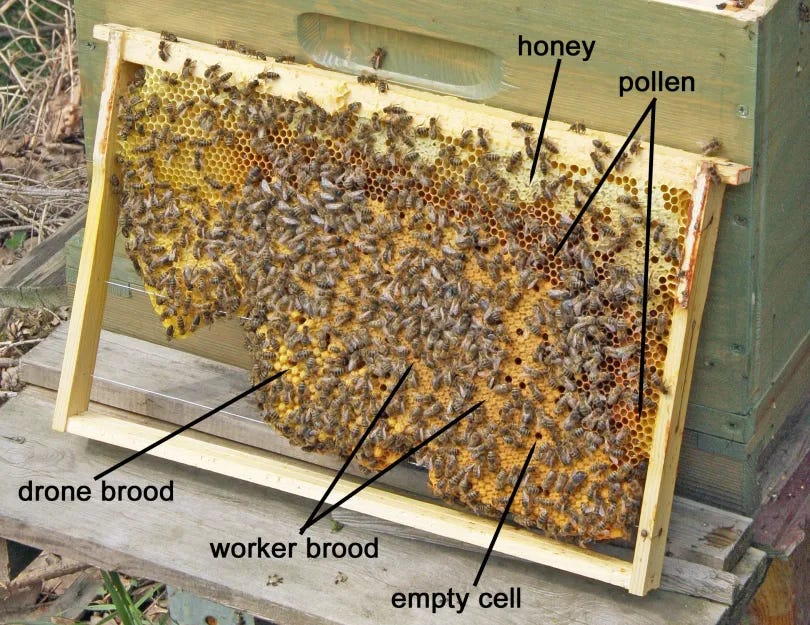

Once warm weather sets in and a steady spring flow is underway, it’s time for the spring inspection. Upon inspection, you’ll notice that some of the frames contain the brood, both open and sealed. This is the nest portion of the hive, which should be put back in place, in the same order, once the inspection is finished. The remaining frames will either be completely empty or will contain a certain amount of beebread and honey. After this, the only time to go back into the hive is for quick checks to see if they need more frames. At this point, it’s April and I won’t be back in the hive until September or so.

If they’re on the second-to-last frame moving away from the entrance, it’s time to add more frames to a topbar hive. If they’re on the second-to-last frame in a Langstroth, it’s time to add a super or a medium. I don’t harvest honey at all during the spring or summer, even if there’s a surplus.

Why, you might ask? Well, how do we stop disease? We don’t move brood around. We don’t open our hives to weaken the colonies, and we are thorough with cleaning old colonies, especially since we know they died from something untreated and likely not starvation. We can also keep our hives far away from each other so they don’t go into the wrong hive. Just simple things add up to making major differences.

We mentioned the importance of preparing our bees by having an appropriate amount of honey stored for them, even if that means less for us. This is the opposite of modern beekeeping. Supplemental bee water, which is basically simple syrup, sometimes with other amendments added, has been the core component of bee diets to prepare them for the spring and to help them survive the winter by giving them cheap carbohydrates.

One principle common to all living things is that an organism weakened by a shortage of necessary substances is most likely to be targeted by pathogenic microorganisms and parasites. And it is simply impossible to avoid such problems unless bees live on a diverse diet.

So at this point, we’ve talked about not adding bee sugar, minimal hive visits, no chemicals, leaving extra honey in the hives, and using deeper hives if it makes more sense in your climate. The Spring checkup is half of the work; making sure the brood nest is dry, removing surplus frames that have been emptied during the winter if you’re using a topbar hive. During the late spring and early summer we start to add the foundation for the bees to start working on. This is where we see a big difference between Langstroth and topbar hives since with Langstroth we add a medium at a time, whereas with the topbars we can add frames as they’re needed, which allows the hive, in my opinion, a better, more gradual growth without too much space too quickly. But, that’s a personal preference.

In the old days, beekeepers considered the start of the primary willow blossoming & the oaks leafing out to be the right time to do bee inspections. I think this is still good advice.

Transitioning to our fall inspection— we generally don’t want to go into the hive until the daytime temperature no longer rises above 54 degrees, if you live somewhere that it drops that low. The reason is simple, that’s when the bees begin to form a winter cluster, so they stay completely out of the mediums in a Langstroth or the side frames in a top bar. I don’t like to use a smoker if I don’t have to, and why not when you can be smarter about it? Now, if there’s clearly not enough honey, for whatever reason, then provide some in a frame feeder inside the hive. In my opinion, it’s much better to feed at this time than to add a honey frame to the nest before wintering.

Now, no matter what you do, hives will eventually die. While a good ‘conventional’ hive might last three or so years, at best, hives have survived in log hives for over 8 years, but typically, a hive will last 3-5 years.7 And that might still seem short, but if you think about it, it makes sense. One, of what you might call, the “purpose” behind the death of bee colonies in nature is to periodically disinfect the tree hollows where they live. When a colony dies, the old, blackened comb left behind in the hollow, along with the pathogenic agents that have built up in it, is destroyed by wax moths and all sorts of other creatures of the forest.

Once this rest has happened, the cleaned hollow is again ready to welcome new and hardworking residents.

That’s really it. Spring cleaning, adding frames throughout the summer, fall prep, and leaving them alone during the winter. More interest in insulating hives has gained traction, and we talked about it a bit particularly in the Langstroth article. The more extreme the climate is where you live, the more important it is to insulate.

The takeaway is that beekeeping has become this huge, complex mess of maintenance that isn’t designed for the bees’ health or safety, but for our convenience. And there’s a check due right now, and unfortunately, we have to pay it, and that’s because of the chemicals we’ve been using. And unfortunately, this is a common thread throughout modern agriculture. With this, we’re done with our beekeeping miniseries. If you want to learn more about treatment-free beekeeping, check out the sources in the articles we’ve released, and of course check out the interviews we did for the series as well, as we had a number of guests with great insights into their own personal successes with treatment-free, natural, or scientific beekeeping— whichever term they choose to use.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to an 11-page chapter, of (so far) an 871-page book with 532 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this episode, #149, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. Suppose you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content. In that case, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Lazutin, F. (2020). Keeping bees with a smile: A vision and practice of natural apiculture. Deep Snow Press.

Seeburger, V., & Hasselmann, M. (n.d.). The production of Melezitose in Honeydew and its impact on honey bees (apis mellifera L.) (thesis).

Cameron, S. A., Corbet, S. A., & Whitfield, J. B. (2019). Bumble Bees (hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus terrestris) collecting honeydew from the giant willow aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research, 68, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.68.30495

https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=1544&sharing=yes

https://projects.sare.org/sare_project/fne10-694/

https://open.sp otify.com/episode/711jCnGtxUw9TVv2EiL2qz

https://open.s potify.com/episode/0RaZtBcuq9macgCCSxiT4W