The narrative from the United States regarding South Korea is one of unflinching success— that the nation rose from the ashes of the Cold War to showcase the successes of neoliberal capitalism that can take root anywhere across the globe. While the history of how and why the flavor of capitalism that has enmeshed itself upon the peninsula has arrived, a quick summary of its history can help us contextualize the nation, and further, help us understand its unique relationship with radical ecology and community-centered agriculture.

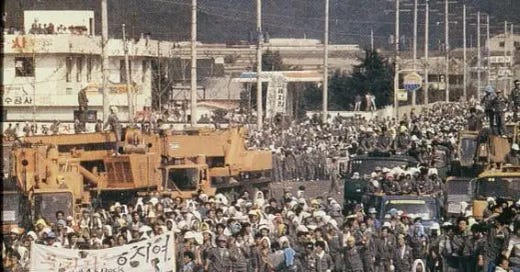

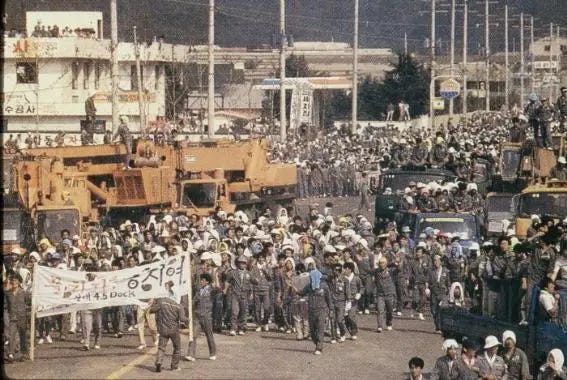

Since 1987, South Korea has seen a rapid rise in what we might call political democratization; that is, the end of the raw corruption the West fantasizes about occurs across non-European countries. The old guards of the Cold War gave way to a softer political power— that’s not to say that authoritarianism, discrimination, and other classic issues of government disappeared, but rather they were simply less unchecked— less brutal in their activities.

Still, in 1997, following the IMF foreign exchange crisis, during which the IMF bailed out the S. Korean government, forcing austerity measures, the economy recoiled and reorganized around economic power and access, driving up unemployment and leaving many to rely on self-employment, with few social welfare systems available.1 Of course, when economic freedom for working-class people dissolves, an ancillary effect is the destruction of ecological protections and democratic concerns with ecology.

As South Korea bounced back in the early 2000s from the economic reform, interest in ecological conservation grew, and across the political spectrum, the belief was largely that the solutions to protect the landscape were centered around strategies to “green the state and society in a top-down manner through the ecological reform of the capitalist state”, which only ever achieved partial success and much to be desired.2 As the reality that this would never solve these issues, an alternative ecological movement grew with a vision to create a sustainable, cooperative society that transcended the limitations of both capitalism and industrialism. The ecological alternative movement emerged as a grassroots response to these failures, championing community-driven ecological and democratic reforms.

This isn’t to say that ecology and environmentalism hadn’t been significant until this moment; ecological protection has long been a central cultural point in the region. As part of political dialogue, the environmental movement was born under anti-pollution efforts in the 1980s, which became institutionalized through NGOs into the 90s, similar to what is common today in the United States. These NGOs focused on sustainable development within the framework of capitalism, using state-centered, top-down approaches that gave lip service to environmental issues as long as they didn’t significantly compromise economic issues. By the mid-2000s, in the wake of the austerity programs forced by the IMF, these movements were largely incapable of driving any change.

In response, several movements sprung up in S. Korea to address the shortcomings of the institutional movements, all following similar tenets. These movements all follow three characteristics. The first is centered on the core actors— these are pro-democracy activists and agroecological farmers alongside housewives. The second is a focus on ecological balance and the intrinsic value of life. It opposes anthropocentric views and advocates for face-to-face, community-based relationships that foster trust and cooperation. Lastly, they rely on local grassroots efforts. These include organic farming cooperatives, consumer cooperatives, and community initiatives that prioritize sustainability and self-sufficiency.

The first movement that found cultural power in response to these failures was the life (saeng-myung) and peace movement. Its focus was on “ecology” rather than the environment and to pursue new systems for how society should be structured.

Centering locality and community resilience instead of attempts to overthrow the capitalist regime is interesting, given the region’s history with various socialist and communist states. Many former activists in the region turned away from state-down power and instead found ecological alternatives, seeking to build communities independent of state and market forces dictating their livelihoods.

With this in mind, it’s no surprise that after the liberal attempts to greenwash capitalism provided no meaningful changes radicals abandoned reformatory practices and found themselves searching for bottom-up, community-driven approaches to democracy and social change. While these same radicals provided the base of the movement’s power in the 1980s, as the movements became institutionalized, the radical eco-socialist framework that had driven the anti-pollution movement was swept under the rug. It’s no surprise then when we see agroecology as a cornerstone of these movements, or that JADAM & KNF are explicitly political practices, as evidenced by the frequent quotes from Marx within the JADAM texts.

From the early 2000s, the evidence of these movements is clear in the rapid increase of consumer cooperative societies, as well as the increase in alternative communities formed both in rural and urban areas, as well as grass-roots organizations such as medical cooperative societies.

So what is a consumer cooperative society? These are consumer (member) owned organizations— think of a grocery store that is owned entirely by the consumers, who democratically choose how they bulk-order products to save money for themselves and to keep the store open also for the general population. While these have become popular in gentrified areas across urban regions of the United States, these movements can include credit unions, housing cooperatives, and even utility cooperatives. Fundamentally, it’s a collectivized way to purchase resources for a community. These movements seek to create alternatives to mainstream markets and industry and to realize them not through declaration, but through the transformation of the way people live and engage with the world around them, influencing their values and culture.

The Hansalim Movement

One of the first major writings from the Korean eco-socialist movement, the “Hansalim Manifesto” was released in 1989, which provides an accessible framework for the eco-socialist movement. It advocated for direct transactions of organic agricultural products, consumer cooperatives, ecology-based communities, and a “return to rural communities” (known as the gwinong movement). Further, the manifesto highlighted the need for local exchange trading systems, and centering and recognizing the need to give attention to peace, community, movement, and life.

The manifesto was born from the Hansalim movement, which was a cooperative movement that started in the Wonju camp in 1972, following the flood of the Namhangang River. This movement was built on the heels of a tradition of autonomous rural village movement in the Wonju area, which had most recently been directed around the civilian Disaster Recovery Committee (the DRC— which was led by local leaders Jang Il-soon & Ji Hak-soon).

To rebuild, they chose to start a movement that campaigned for joint use and ownership of tools, machines, credit, and production. However, it failed, as it still relied on external inputs— machines, livestock, and capital.3 When this failed, instead of accepting to re-integrate into capitalist society, they chose to launch a cooperative movement of producers and consumers through the selling of organic agricultural products.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Poor Prole's Almanac: Restoration Agroecology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.