The 20th century Permanent Agriculture Revolution

That one time the United States almost accidentally stopped climate change and became a leading global force in defense of ecology. Part 1

Following the civil war, agriculture had fallen apart– mortgage debt, excess production, and high shipping rates charged by railroads decimated farmers. This ultimately led to the Patrons of Husbandry being formed in 1867, also known as the Grange. While initially for educational and social purposes, they quickly shifted to pursue cooperative business arrangements by the 1870s.1 Within a decade the organization started to fade, but was followed by a more militant and political Farmer’s Alliance.2 They continued to advocate for cooperative business models, specifically around marketing and buying at scale. During this same time, in 1880 specifically, farmers in Kansas organized to form the first major agrarian political party in the country, known as the People’s Party, based largely on the goals of the Farmer’s Alliance.3 They pushed for a number of very progressive actions, including antitrust legislation, government ownership of railroads to reduce shipping costs, a progressive income tax, and direct representation within the government.

The movement was moderately successful, but lost momentum after the party’s defeat in the 1896 election.4 Part of this was because pricing parity came into effect as commodity prices rose faster than farm expenses over the next 2 decades, erasing the urgency behind the organization. There’s a number of factors involved with why commodity prices increased, but one of the big ones was that this was one of the periods with the most immigration to the United States in our history.

Following this, the Great War (World War One) erupted, further pushing up commodity prices as much of Europe was ravaged, but after the war, as things returned to normal and Europe was undergoing massive reconstruction, market competition returned and the massive surpluses that farmers had relied on to sell overseas saturated market demand and prices collapsed.

By 1921, 3 years after the end of World War One, prices had only recovered up to 67% their previous highs. Again, organizations sprung up in response to this— in North Dakota, for example, the Nonpartisan league argued for state owned banks, grain elevators, flour mills, and meat-packing plans.

However, at this same period in time we begin to see a division form in rural America, as farmers who had weathered the storm and came out on top found this to be an opportunity to expand and purchase failing farms cheaply. In 1919, these particular farmers formed the American Farm Bureau Federation, who were explicitly against basically everything the Nonpartisan league advocated for, and supported projects like ‘privately held federal land banks’ and expanding extension services and land-grant colleges. This organization and their work was the basis for a lot of what we see decades later in places like Mexico, India, and Africa in the name of progress.

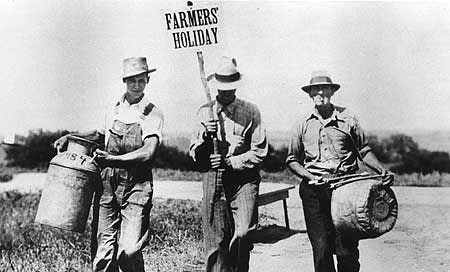

The counterweight to the AFBF was the Farm Union, who pushed for cooperative projects, and also pushed for things like sales strikes to push the government to guarantee farmers their production costs plus a small profit—we talked about this a bit in the corn episode. In 1932, this culminated in a formal attempted closure through a self-mandated ‘holiday’ by the Farms Holiday association at the state fairgrounds in Des Moines, Iowa. This turned violent when the National Guard came in and beat the striking farmers. These are the same practices that were later applied to block foreclosure sales by bidding pennies at auction and threatening bank officers should they fail to accept the sale proceeds as full repayment.5

While the dust bowl gets plenty of well-deserved attention, the other thing that was happening during this time that is not well-known is that much of the country was also flooding around rivers. It not only felt catastrophic, it WAS catastrophic. Henry Wallace, who would go on to be the Secretary of Agriculture, was quoted as saying “human beings are ruining land, and bad land is ruining human beings, especially children”.

It was around this time fears about societal collapse and food systems collapse became more mainstreamed, and justifiably so. Discussions around civilizations collapsing when soil collapses became more common, and Walter Lowdermilk, a prominent soil scientist of the time, after returning from a trip through Africa & the middle east, described his visit as a “graveyard of empires”. Of course, we now understand it was more complicated than just soil degradation which led to those collapses, and the examples he gave included things that actually helped protect soil health. For example, he blamed the Mayan collapse being predicated on using all of the land for corn production, even hillside patches, which led to mudslides. We know now this wasn’t the case, but speaks to how the fear of soil degradation infiltrated our very understanding of how societies thrived.

The example that was most valuable to these visionaries of a different system of living was the Chinese, where they’d seen landscapes devastated by conventional tilled agriculture, but in many places they had been restored and managed ethically with various tools such as dykes, terraces, and more. Paul Sears, an author and soil advocate, says in one of his books that what made Chinese stewardship successful was a “sense of belonging to a particular place on earth”. The critique that blew back on American practices was quite literally the American aspect of it; arrogance and the need for indefinite growth.

While we’ve seen bits of socialist, communist, and anarchist organizing in rural spaces through these various organizations, Leftist ideals had become more mainstream over the late 19th and early 20th century as the illusion of the American vision of perpetual growth and excessive individualism became more and more unrealistic on a planet with finite topsoil.

Searching for a Cause

What had caused this degradation? More specifically, what caused this poor land ethic? Hugh Bennett, who would become head of the Soil Conservation Service, articulated that

“White men found America a continent more lush and fertile than they had dared imagine. For a century, they pushed the frontier westward, and always found virgin land. Gradually... National land philosophy evolved. It was a philosophy of exploitation… a philosophy that permitted a man, in good conscience, to destroy his land and move onward to new and fertile lands.”

This developed into a movement of anti-technology, which would come head to head with the post World-War 2 boom, thanks to the development of the American war machine’s excess resources.

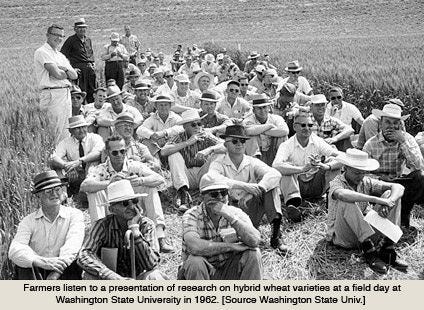

But before we get there. We had talked about the American Farm Bureau Federation previously; they advocated for a lot of the things we see today— extension schools and land-grant colleges and so on— they were successful in implementing these changes. Now, land-grant colleges had existed through the Merrill Act of 1862, and they were expanded in 1890 to force confederate states to provide equal education for people, regardless of ethnicity, but in 1914— during that period of pricing parity— The Smith-Lever act was put into place, giving land-grand colleges the resources to bring their research to the farmers, as opposed to existing simply as a destination source for farmers looking for the most cutting-edge research.

While little evidence exists on the immediate impacts of this, I’m suspicious about how much this impacted the incorporation of new technologies, especially capital-intensive equipment, which didn’t increase yields, as yields were largely stagnant for the following 3 decades. While the evidence today is limited to prove or disprove this argument, folks like Ralph Borsodi, an agrarian theorist and economist, argued that land-colleges existed to “teach the rape of the earth and the destruction of our priceless heritage of land, impoverished our rural communities, wipe out our rural schools, close our rural churches, destroy our rural culture, and depopulate the countryside upon which all these depend”. In his view, the USDA & the land-grant colleges fostered Big Farming and were tone-deaf to the needs of local ecology by demanding farmers invest in capital-intensive technologies and monocrops. 6

The alternative to this system was quite literally a counterweight to what land-grant colleges advocated; diverse, perennial crops guided by local ecologies. This became known as permanent agriculture.

A Declaration of Interdependence

While American exceptionalism was a defining trait in American identity in the early 20th century, during the 1920s and on hyper-individuality became nearly sacred. The advocates for a new agricultural system knew it would be impossible to present an alternative without addressing the need to find value in interdependence. Henry Wallace advocated for a “Declaration of Interdependence” in 1934; that we were inevitably connected not only to one another but to the soils, to the farms, and ultimately to the ecology, which was also, as a field of study, gaining more and more recognition. Interdependence was fundamental in this understanding, and you could not fix the soil without fixing the relationship between agriculture and ecology.

This spoke to the interconnectedness of every function of our existence; it was understood that everything from ecology, agriculture, construction, engineering, water management— everything was predicated on our relationship and respect for the needs of the soil. In the words of author and soil advocate Stuart Chase, “We are all creatures of this earth, and so are part of all our prairies, mountains, rivers, and clouds. Unless we feel this.. We may know all the calculus and all the Talmud, but have not learned the first lesson of living on this earth.”

Ultimately, what stood at the core of the people who advocated for a change towards permanent agriculture was the understanding that the system was broken, disaster was imminent without change, but there was still time to avert a national, if not global, crisis. Rexford Tugwell, an economist, soil advocate, and later part of the inner circle around FDR, even further advocated for a vision in which “a good citizen regards himself not as an absolute owner of the soil but rather a manager set in charge of using it wisely. His duty is one of passing on to succeeding managers a soil which is as good as, or better than, when he found it.” This is a far cry from the direction agriculture had taken for decades.

The Beginning of a New Era

On March 4th, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sworn in as the 32nd president of the United States. Given the turmoil across the country between the dust bowl and the Great Depression, advisor Samuel Rosenman advised him to identify a Brain Trust—academics whose knowledge would help guide a number of policies that would fundamentally reform the entire nation. Much of the Brains Trust would be academics from Columbia, such as previous mentioned Rexford Tugwell, who we know at least shared letters with J Russell Smith, notoriously known for his advocacy of native perennial tree crops. Morris Cooke, another important voice in advocating for permanent agriculture, was an engineer who would later be responsible for the electrification of rural America. The last major figure that had FDR’s ear was Hugh Bennett, who as we stated earlier, became the head of the Soil Conservation Service.

What was being presented was an alternative to the American way, for better or worse, and while the idea of planning our agricultural economy wasn’t necessarily new, the scale and scope were, and permanent agriculture meant the diets of Americans would have to shift. Despite the economic, cultural, and political barriers, FDR’s programs backed this vision. The administration founded the Agricultural Adjustment Administration in 1933, which worked to stabilize commodity pricing by buying excess from farmers in order to support the farms of the present while also founding the Soil Conservation Service in 1935, all of which helped cement the government’s relationship and fundamental role in food production within the United States.

More radically, programs like the Resettlement Administration, which was headed by Rexford Tugwell, worked to address the plight of tenant farmers whose livelihoods had been destroyed in the dust bowl.7 The RA set up tenant communities which provided basic housing, clean water, and even daycare services for migrant farmers.

Stories from these camps range widely, and red-baiting; that is, accusing its leaders of being Marxist, Communist, or Anarchist led to Rexford stepping down and the program being closed a decade later.

Many large farmers despised the RA because it offered an alternative to the harsh management and conditions migrant farmers had to work. The camps in California inspired John Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath”, after learning the plight of the migrants who had traversed the country in search of a better life.

Arthurdale, West Virginia is possibly the most well-known project due to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s involvement; it was a planned community with a post office and modern plumbing. There were no private sector jobs, except for one factory which supplied parts to the USPS, and it was quickly attributed to the communist tendencies of the FDR administration. While the initial plan had been that the residents would be somewhat self-sufficient through small homestead plots, and organizers even specifically chose individuals with an agricultural background, it was quickly obvious that they would never actually be anything close to self-sufficient, and by many counts the program was a failure. However, residents often reflected that their time in Arthurdale was one of the best moments of their lives.

Now, Rexwell was the brains behind the RA, but he wasn’t just behind the scenes, he was also the voice of the project, and was effective at explaining the complexities behind food systems and ecology.

Rexwell is an interesting figure; like many soil defenders at this time, he was drawn to soil conservation while teaching in the northeast. He was considered a colorful economics professor at Columbia, and was a colleague of Scott Nearing, the man who would later lead the Back to the Land movement, and someone we will touch on later. Prior to his time at Columbia and before he was a public figure, he taught at the University of Pennsylvania and overlapped with J. Russell Smith, who also taught in the economics department.

Needless to say, Tugwell was a public face for a fundamental shift in what food systems looked like in the United States, a new vision of food pushed largely by economists, and he often spoke publicly about the need for a planned, balanced economy in the face of the great depression to the point of explicitly criticizing individualists who confused “identification of capitalism with democracy”. It was the goal of Tugwell and other economists interested in soil conservation to correlate planned agriculture with democracy; that farmers destroying soils for today’s crops were balancing the future costs to the general public, and it was the responsibility of all citizens to consider and care for the soils on our farms, a point FDR advocated.

Strange, M. (1988). Family farming: A new economic vision. University of Nebraska Press.

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/farmers-alliance/

Beeman, R. S., & Pritchard, J. A. (2001). A green and permanent land: Ecology and agriculture in the twentieth century. University Press of Kansas.

Hurt, R. D. (1994). American agriculture: A brief history. Iowa State Univ. Press.

https://www.councilbluffslibrary.org/blog/farmers-holiday-strike-of-1932/

Kirkendall, R. S. (1982). Social scientists and farm politics in the age of roosevelt. Iowa State University Press.

http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/archives/collections/franklin/index.php?p=collections/findingaid&id=172