While we are all familiar with the staples of our modern diet and the role maize has played in the development of modern civilization, there was once domesticated crops that revolutionized the way people lived in North America long before maize arrived. Enter the Eastern Agricultural Complex, a central location in the development of domesticated crops across eastern North America hundreds of years before the arrival of corn. The indigenous people who occupied this region were diverse, but have been, for lack of clearer language, categorized under the grouping of the Adena.

The Adena were located in the modern-day area of southern Ohio and northern Kentucky. The archaeological record suggests that humans were collecting these plants from the wild by 6000 BC. In the 1970s, archaeologists noticed differences between seeds found in the remains of pre-Columbus era Native American hearths and houses and those growing in the wild. In a domestic setting, the seeds of some plants were much larger than in the wild, and the seeds were easier to extract from the shells or husks. This was evidence that Indigenous people selectively bred the plants to make them more productive and accessible.

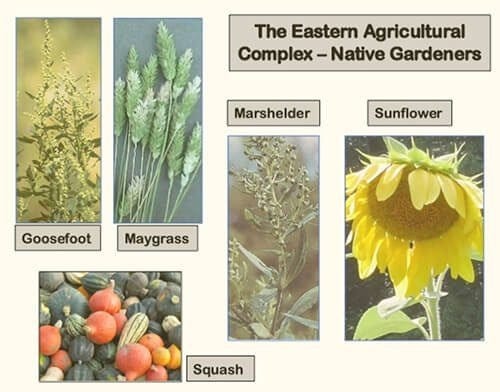

While many were lost when corn traveled further north, such as marshelder, giant ragweed, maygrass, and many more, some are still with us today, such as sunflowers and squash. While domesticated, the seeds were still small, and compared to say, hickories, acorns, or hazels, the caloric return per hour of labor was significantly lower.

The point is, they were a lot of work for not a lot of return. A traditional argument on the subject matter is that it was a supplemental, backup food that could fill in during years with low nut drops and that it was basically for emergencies and occasionally extra caloric intake. Despite all the research I’ve reviewed on the subject, the idea that maybe they just liked having a different option wasn’t ever suggested. It didn’t have to be about efficiency any more than any other food production we are involved with, right?

So what exactly were they doing with these fun and exciting new crops? Chances are, these were plants they found near the trees they were harvesting from, and selectively picked the ones with the thinnest shells and largest seeds.

Now, I want to take some time to look at this domestication process and how that played out in the community. Part of this is because there’s very little evidence around foodways for the Adena; the Adena are most recognized for their unique funerary practices. The first is that the wood used for burning based on charcoal records came from a handful of trees; black locusts, red mulberries, hickory, and oak— all coppicing trees. Hickory and oak make up 70% of the charcoal. Now why are we talking about trees used for burning? Because it tells us a bit about what was around them since few species were left unused.

The shell remains from nuts come from hickory, acorns, black walnuts, butternut walnuts, and hazelnuts. That said, 90% of the shells found were from hickory. Walnuts came in a significant second, and only a few hazelnut & acorn shells were found. Of the seeds found, there were nine distinct families identified: maygrass, goosefoot, erect knotweed, and sumpweed being the most recognized members of the EAC– the Eastern Agricultural Complex.

Maygrass is particularly interesting because it is considered to be out of its range, which suggests that it was intentionally planted. It also made up about 60% of the burned remains, suggesting it was a main seed for food. Of all the seeds found, EAC plants made up 76% of the identified seeds, as well as some weeds that we have no evidence that they were being domesticated but were likely foraged.1

Of the EAC, the most recognizable plants we know today are sunflower, lambsquarters, and even pigweed, which is only called pigweed because people consider it an annoying weed today, even though it’s a domestic version of quinoa. The plants are broken down into ‘oily’ and ‘starchy’ plants. Or rather, which plants produce fats and which can be stored as flour. And then there’s the gouard squash, which didn’t really have palatable meat but the shell was a good storage vessel and the seeds were edible.

So let’s talk about this transition from a predominantly hickory diet to a seed-based diet. While the species that were harvested didn’t seem to change too much over time before maize, what is interesting is the transition throughout the woodland time periods of moving away from hickory. While hickory made up 95% of nut shells throughout the early and middle woodlands, by the late woodlands it had dropped to 78% and walnut and hazelnut made up the rest.

Coincidentally, the percentage of seed material in the charred materials also jumped 50-fold from the early to late woodland period, with 90% of that change happening between the middle and late. What this all means is that around 1,000 years ago the diets significantly changed for the Adena from being primarily hickory-based to equal parts hickory to seed— mostly maygrass. Analyses of pollen and charcoal confirm that there was a clear change in forest composition around 1000 to 800 BC. Forests were cleared, and fire-tolerant species became better represented in pollen cores, while the pollen of fire-intolerant species became rare.

What’s interesting is that maize was introduced to the region around 2,000 years ago– 1,000 years before the diets changed from hickory to seed, and corn clearly wasn’t adopted quite yet. Tropical maize does not flower under the long day conditions of summer north of what is now called Mexico, requiring genetic adaptation. It seems that maize was adopted first as a supplement to existing local indigenous agricultural plants, but gradually came to dominate as its yields increased. But this process took quite a while, and maize didn’t become a staple of their diet for a thousand more years.

So let’s look at this interesting process of domestication and selective breeding; because it’s really important in understanding the relationships between communities like the Adena and horticulture itself. For the domestication of these species to happen, a confluence of events had to take place. First, let’s talk about place: this region is also known as the prairie peninsula: a prairie-woodland mosaic that was maintained by anthropogenic fire starting as early as 6000 years ago and covered with rivers.

Scholars have pointed out that many of these original plants that were domesticated were plants that thrived in disturbed soils in river valleys. In the aftermath of a flood, in which most of the old vegetation is killed by the high waters and bare patches of new, often very fertile, soil were created, these pioneer plants sprang up like magic, often growing in almost pure stands, but usually disappearing after a single season, as other vegetation pushed them out until the next flood. This was the same location where they’d be harvesting black walnuts and likely fishing and hunting. Black walnut trees are relatively resistant to fire and younger trees often re-sprout after a burn. They do well on disturbed sites but not in closed forest canopies. Most grasses and herbaceous plants are also juglone tolerant (a subject we talk about extensively here).

Walnut, as we pointed out previously, was abundant near historically recorded indigenous villages, suggesting that they also do well in anthropogenic landscapes. In short, black walnut trees are late successional components of anthropogenic niches created by burning, likely found near riverbanks.

Prior, we pointed out that the char remains that showed the transition from a nut-based diet to seed-based, and during the period where hickories went down but before seeds took over, black walnuts were one of the main substitutes.2 So, the primary narrative is this: in gathering the seeds some were undoubtedly dropped in the sunny environment and disturbed soil of a settlement, and those seeds sprouted and thrived. Over time the seeds were sown and the ground was cleared of any competitive vegetation. The seeds which germinated quickest (i.e. thinner seed coats) and the plants which grew fastest were the most likely to be replanted.

Through a process of unconscious selection and, later, conscious selection, the domesticated weeds became more productive. The seeds of some species became substantially larger and/or their seed coats were less thick compared to the wild plants. Conversely, when the Adena quit growing these plants, as they did later, their seeds reverted within a few years to the thickness they had been in the wild.

Now, I don’t fully buy that, for a couple reasons. I think it erases a very, very close relationship between these people and the lands into a transactional affair, and we know that’s never been the case. Further, we have new evidence which suggests there was even more at play to domesticate crops.

But to understand this, we need to talk about these grasses and weeds a bit more. When we talk about their role, they’re considered most successful in human-created early successional ecosystems or “disturbance”. This begs the question: where did they occur before humans modified the ecosystems of eastern North America? Where would late Pleistocene and early Holocene foragers have encountered such weedy plants? It has been suggested that domesticated plant populations became isolated from their wild relatives when people removed these floodplain species from the risky and unpredictable environments in which they had evolved and began to cultivate them in upland clearings created using fire.

Previous domestication theorists have focused on the relationship between the lost crops and floodplains because water is the most obvious force of disturbance within the area. What’s often ignored though is that large swaths of these riparian woodlands were covered in a prairie-savannah-forest mosaic throughout the Holocene. In recent years, bison have been reintroduced to tallgrass prairie remnants for the first time in over a century, and some interesting findings have come out about it.

While it might seem weird, recent research has shown that bison were also present in this prairie peninsula throughout the Holocene. Like rivers and humans, bison create early successional habitats for annual forbs and grasses, including the progenitors of eastern North American crops, within tallgrass prairies.3 Fieldwork has shown that crop progenitors are focal members of plant communities along bison trails and in wallows.4 Some researchers, and this is just in the past few years, argue that ancient foragers encountered dense, easily harvestable stands of crop progenitors as they moved along bison trails, and that the ecosystems created by bison and anthropogenic fire served as a template for the later agroecosystem of this region.

Now, I want to quickly talk about that process of domestication, because I think it’s an important thing to understand, and then I want to talk about how this impacted the society and how it organized.

Erect knotweed is estimated to have been domesticated between 700 and 1000. It produces edible seeds that are encased in a hard pericarp, or fruit coat. Erect knotweed exhibits seasonally controlled fruit dimorphism, which means that individual plants produce two distinct fruit types in ratios that vary throughout the growing season. The two morphs are called smooth and rough with reference to the surface texture of their fruit coat. Basically, during the summer and early fall, plants produce only rough morphs. Beginning in mid-September, plants begin to produce both rough and smooth morphs.

Now why does this matter? The only functional difference between them is that smooth morphs have thinner, less water-resistant fruit coats and will germinate immediately the spring after they are produced, whereas rough morphs can survive in the seedbank for at least 18 months. The have a short-term seed for the next year and then the emergency seed if the floods come at the wrong time.

Now, with erect knotweed, we have a plant that naturally produces a fruit type that already has one key characteristic of a domesticated seed crop: thinner fruit coats. Human selection was brought to bear on this natural variation during the process of domestication. So let’s look at domesticated erect knotweed, and see how it’s different. There’s mainly 2 things that are different here; it’s seeds are larger, and rough morphs are reduced or eliminated in favor of smooth morphs.

To summarize, domesticated erect knotweed is probably the results of both active human selection and the relaxation of certain selective pressures in human-mediated ecosystems.

Now I want to talk about plasticity. Plasticity is particularly important when we look at plant domestication. Now, with diversity, new traits come up, right? And for plants and animals, if you have new traits, you can go use that specific trait where it might be most suitable. Plants, however, can’t just pick themselves up out of the ground to move somewhere that fits a trait they might have developed by accident. Instead, plants have plasticity, which allows them to have a wide scope of traits that come out, depending on their very specific environment.

A super simple example is how trees grow. Densely planted trees, like when we’re coppicing, can be trained to grow super tall with few branches, versus short and wide, and that’s completely dependent on the environment they’re in.

Now, like the other plants of the EAC, erect knotweed came from the floodplains, that riparian zone where black walnuts thrived. As people moved away from these floodplains 2,000 years ago, which we don’t know the reason for, what we do know is that erect knotweed came with them. Now, new plants in new environments will explore these new traits.

But let’s circle back to the fruiting process— having two types of seeds, a short-term and a long-term, is a form of evolutionary bet-hedging. Organisms that are evolutionary bet-hedgers exhibit strategies that do not maximize the survival of their offspring within a single generation, but which instead tend to reduce variation in survival rates over many generations. In the case of erect knotweed, most rough-coated seeds do not germinate the spring after they are produced, which means that they are subject to an entire year of potential predation and pathogen risks before they germinate. Even once they do germinate, they grow more slowly than seedlings sprung from smooth morphs, meaning that they are less competitive where dozens of different weedy species compete for light and space. In short, a mother plant that uses resources producing rough morphs that could otherwise be used to produce smooth morphs is not maximizing its fitness for the next generation— so why has the production of rough morphs evolved, and how is it maintained?

In order for this protective fruit dimorphism to be eliminated under cultivation, Dr. Natalie Mueller, likely the most knowledgeable living person when it comes to the EAC, has suggested that farmers were protecting populations of erect knotweed from the effects of unpredictable flooding, both by creating clearings for erect knotweed seedlings in micro-topographic zones that rarely or never flood and by storing seed stock, which provided an alternative to the soil seed bank.5,6 This repeated reduction of stress from unpredictable floods and careful seed selection likely led to the domesticated crops they harvest within a few hundred years, although it may have been significantly quicker. And to help accelerate the seasonal cycling of nutrients, burning was used to remove stubble from the previous harvests, cycling those nutrients once again.

Dr. Mueller also brought these domesticated plants back to life by testing the plasticity of goosefoot, showing that it responds quickly to domestication and that our understanding of the evolutionary transition might be considerably different than reality.7 Growing goosefoot in a conventional garden showcased many of the traits exhibited in seeds discovered on sites, reinforcing that domestication was at play and not some random coincidence or evolutionary irregularity.8

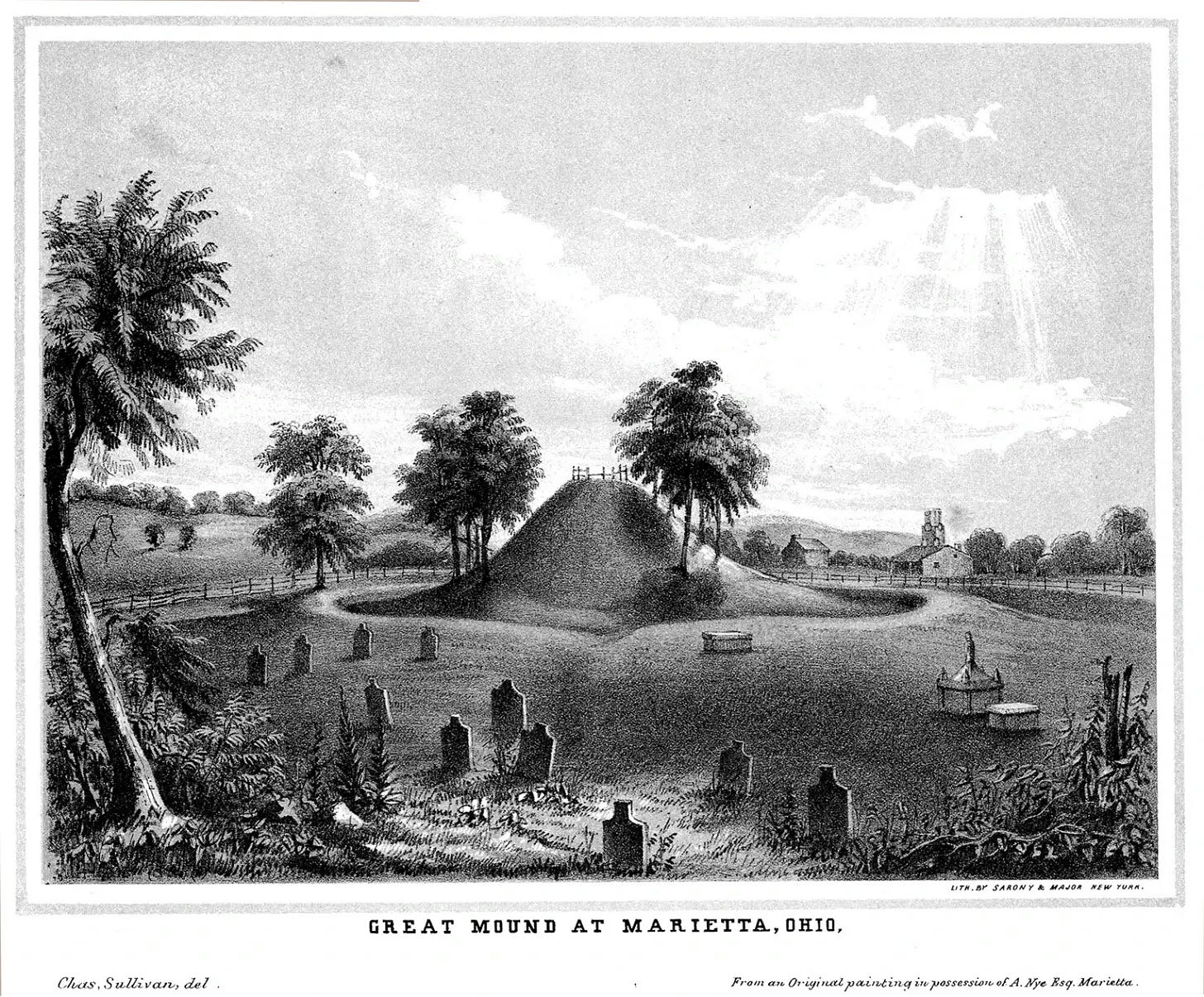

This raises an important point— successful farming at this scale requires community, right? Despite appearing that they would need to settle in one place, the Adena instead chose to remain mobile, probably in part due to sustained success in hunting and gathering activities. Further, there’s evidence of long-term investment in the region based on the monuments made. Monumental earthen burial mounds and geometric ditch and embankment enclosures symbolize a shift in the ways that people valued the landscape, engaging in communal labor to signify their bonds to it and to one another.9

These practices unified separate communities into an organizational lattice where labor and ritual practices were fused to produce monumental earthen constructions that held elaborate mortuary remains — some of which appear to be aligned with astronomical movements.10

What we also know is that these communities have left no evidence of a hierarchy in how their communities were organized, no evidence of chiefs or any other structured, formal governance.11 The most recent research suggests that complex inter-relations through kinship forced communities to have an investment in the successes of one another while helping reduce the risks of a power vacuum within the community.12 By examining the role of kinship in these coalitions, we draw attention to the processes through which situational leadership and influence were organized in a heterarchical manner.

The concept of heterarchy is an interesting one if you’re not familiar with it. It’s the idea that while all individuals in a community are equal and capable of taking any role in the community, temporary leadership is given or gained based on skills and unique circumstances. In this process, there are no permanent powers given, and the goal is that people or groups given temporary authority based on the conditions have this power under tension—that it’s clear the power is temporary and expectations within the community are for that power to be given up as soon as possible.

How groups created and managed dissonance helps us understand the processes through which temporary coalitions could be understood to form, operate, and be abandoned and can help us envision how positions of leadership and authority ebbed and flowed across groups/individuals, as well as through time.

Remains from these burial mounds suggest that individuals frequently had children with people in the communities around them, linking these two regions together through not just these massive, regional ritual practices and ideological beliefs, but also through familial relations. And the burials were a key component of organizing and supporting this system of heterarchy.

The actions of temporary leadership and levels of success would have been assessed by others, leading to real-time evaluations of their accountability to the group to perform important roles, like organizing and leading hunts, ritual ceremonies, or whatever might be urgent. An individual’s worth to the group would have increased as positive accountability was sustained over their lifetime. The temporary and situational status positions of worthy individuals, therefore, could be translated into durable forms of memorialization, such as access to monumental burial or material wealth.

Under these circumstances, agreement to comply with a worthy individual and their allies will be situationally dependent, leading to a complex and overlapping network of shifting power and influence through time. The temporary and shifting forms of leadership positions that are the hallmark of heterarchical organizations are visible in the archaeological record through the different ways that groups came together to memorialize certain individuals during communal mound construction.

So what came first, the heterarchy or the mound? Here’s the thing; mound monuments have existed in the modern United States for at least 7,000 years. In this region, though, as far as I could find, no mounds existed before 2,000 or so years ago.

What we don’t know is how the domestication of crops impacted how this organization operated, but based on the continuation of the mounds through the domestication process and the inclusion of seeds in the burial practices of the mounds, these crops were valued. Although to be fair, the harvesting of these crops was occurring, but not at the scale of the later years. It raises the old question when people talk about like, rewilding a landscape—when is the ‘original’ point? Does the collapse of a society, as the Adena disappeared, suggest that it wasn’t worth recognizing as good, and is it necessary for good things to last forever to be good or to be proof of its successes?

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 15-page chapter, of (so far) a 1020-page book with 677 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episodes #84, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Zeanah, D. W. (2017). Foraging models, niche construction, and the Eastern Agricultural Complex. American Antiquity, 82(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2016.30

Johanson, J. L., Hollenbach, K. D., & Cyr, H. J. (2019). Food production in the early woodland: Macrobotanical remains as evidence for farming along the riverbank in Eastern Tennessee. Southeastern Archaeology, 39(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0734578x.2019.1701364

Spengler, R. N., Petraglia, M., Roberts, P., Ashastina, K., Kistler, L., Mueller, N. G., & Boivin, N. (2021). Exaptation traits for megafaunal mutualisms as a factor in plant domestication. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.649394

Mueller, N. G., Spengler, R. N., Glenn, A., & Lama, K. (2020). Bison, anthropogenic fire, and the origins of agriculture in eastern North America. The Anthropocene Review, 8(2), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019620961119

Mueller, N. G. (2018). The earliest occurrence of a newly described domesticate in Eastern North America: Adena/Hopewell communities and agricultural innovation. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 49, 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2017.12.001

Mueller, N. G., & Flachs, A. (2021). Domestication, crop breeding, and genetic modification are fundamentally different processes: Implications for seed sovereignty and Agrobiodiversity. Agriculture and Human Values, 39(1), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10265-3

Belcher, M. E., Williams, D., & Mueller, N. G. (2023). Turning over a new leaf: Experimental investigations into the role of developmental plasticity in the domestication of goosefoot (chenopodium berlandieri) in eastern North America. American Antiquity, 88(4), 554–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2023.54

Mueller, N. G., White, A., & Szilagyi, P. (2019). Experimental cultivation of eastern North America’s lost crops: Insights into agricultural practice and yield potential. Journal of Ethnobiology, 39(4), 549. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-39.4.549

Henry, E. R., Mueller, N. G., & Jones, M. B. (2021). Ritual dispositions, enclosures, and the passing of time: A biographical perspective on the winchester farm earthwork in Central Kentucky, USA. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 62, 101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101294

Henry, E. R., Shields, C. R., & Kidder, T. R. (2019). Mapping the adena-hopewell landscape in the Middle Ohio Valley, USA: Multi-scalar approaches to LIDAR-derived imagery from Central Kentucky. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 26(4), 1513–1555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-019-09420-2

Henry, E. R., & Barrier, C. R. (2016). The Organization of Dissonance in Adena-Hopewell Societies of Eastern North America. World Archaeology, 48(1), 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2015.1132175

Weitzel, E. M., Codding, B. F., Carmody, S. B., & Zeanah, D. W. (2020). Food production and domestication produced both cooperative and competitive social dynamics in eastern North America. Environmental Archaeology, 27(4), 388–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2020.1737394

Amazing work you guys are doing. Keep it up!

Thanks for this!