The Forgotten Butternut

Following the path of the American Chestnut-- First as Tragedy, then as Farce

The butternut walnut is arguably the least known nut tree across eastern North America. Often called the white walnut or the oil nut, it grows throughout the northeastern United States. Once a prized tree for furniture-making, carving, and boats, as well as the delicious nuts, it’s mostly been lost to history today. Unfortunately, its story is similar to the American Chestnut. Butternut Canker Disease (caused by the fungus Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum), was first discovered in the 1960’s (although it may have been in American forests earlier) and has slowly decimated butternut populations across the country, with few regions to the north still showing little signs of butternut canker.1

Before we dive into butternut canker and whether or not we can solve the issue, it’s worth exploring what makes the butternut so unique. While the butternut and the black walnut overlap, the butternut tends to have a slightly further north range and doesn’t extend as far down south. Their range has historically expanded from southern Canada through Minnesota and down to Arkansas and into Georgia.2 Despite this, they are often found in the same environments; they both enjoy more moist, rich soil, although the butternut can prove to be more successful in drier, rockier soils than the black walnut.3 Their northerly range makes them one of the hardiest walnuts, with reports of surviving -40 Fahrenheit. Being a walnut, they also have the same questions around juglone that we addressed here, and unlike the walnut, the flavor of the butternut is much closer to a pine nut than a black walnut.

Butternuts are also considerably smaller trees than black walnuts, and also show faster growth, being one of the few nut trees that are considered an early succession species much like the American Chestnut had once been as well as the hazelnut. Historically, butternut exists in mixed hardwood forests as scattered, individual trees, similar to black walnuts and chinquapins, at a rate of typically a few per acre.4 This doesn’t account for its important role in several different forest ecosystems as a food source for wildlife.

Typically, butternut is found in sugar-basswood, yellow-poplar-white oak-northern red oak, beech-sugar maple, and river birch-sycamore forest types.5 The reason I bring this up is to point out how the butternut, and its current erasure from the landscape, impacts a diversity of ecosystems, and not simply one particular type of forest. They’re often found around yellow birch, hickories, elms, beech, black cherries, white ash, red maple, poplar, and white pines— again, highlighting the wide range of ecosystems in which it thrives.

While butternut and black walnut are the two walnuts native to North America, they are not part of the same taxonomic sections of walnuts— butternut is part of the Trachycaryon section and is the only member. Butternut is genetically separate enough from black walnut that it doesn’t hybridize, although it does hybridize with the section Cardiocaryon, which includes Japanese walnuts, but also Dioscarynon which includes English walnuts.6 This is important in understanding how it has existed separately in the forests alongside black walnuts and also how and why breeding work to save the butternut has been focused on hybrids with Japanese walnuts, as we’ll discuss. Despite its inability to hybridize, black walnut is often used as rootstock for butternut cultivars.7

Butternuts typically do not produce meaningful amounts of nuts until about 20 years old and hit a peak production between 30 and 60 years. They will start producing as early as seven years old, but not in any meaningful amount. They produce fewer, but arguably higher-quality nuts than black walnuts, and have historically been used similarly to hickories— boiled for oil extraction after crushing.8 The trees are also tapped for a syrup similar to black walnut syrup or maple syrup, and the shells, like black walnuts, are used as a fabric dye. The bark was also used for canoes by the Iroquois.

The Iroquois are believed to have increased butternut populations, based on pollen records, between 6,000 and 4,500 years ago, along the Northern Iroquoian territories.9 This helps explain why the black walnut never gained any meaningful place in much of the northeast as a food crop— the butternut did much of what the black walnut could, and more. The butternut was used for several different things, including crushing and boiling the nuts, similar to hickory, to create something similar to baby food while also scraping the oil off of the boil, and the liquid was often drunk. This milk was, like black walnut milk, mixed with maple syrup and also used to flavor breadcakes and corn soup.10

Butternuts also stand out because they have the highest protein percentage at 30%, above even venison and hazelnuts, at 22 & 25%, respectively.11

They’re also high in fat and low in carbohydrates, making them stand out as a particularly potentially valuable crop.12 Historically, they have been considered a minor crop for indigenous groups, there have been some examples where it has been a bigger staple. For example, in southern Ontario, butternut shells were the vast majority of nut shells that were found in excavations with 222 grams of butternut shells, in comparison to 11 grams of acorns and even fewer from other crops considered to be staples like hickory.13

Further evidence of management by indigenous groups is evident in testimonials from colonists who described, in the Niagara River watershed, “great quantities of butternuts and walnuts and a nice stream”.14 These areas of managed butternuts have extremely high percentages of butternut shell, at 60% or more of the remaining shells at many sites, such as around the Susquehanna Valley.15 Because of the rarity of sites that show significant use of butternuts, this evidence has often been discarded as an anomaly, but its high protein & fat content suggests that the Iroquois were well aware of its value as a food source and likely utilized it as much as possible.

What’s fascinating about the butternut in particular is that the butternut, based on various sites, remained the most popular nut across various periods. While the black walnut, oak, and hazelnut came and went in popularity, sites that had high butternut populations maintained high butternut populations through the early, middle, and late woodland periods. Evidence of groves in the Mohawk River valley suggests that these were planted and maintained by the Iroquois purposefully and continued to value it as a crop above most if not all others.

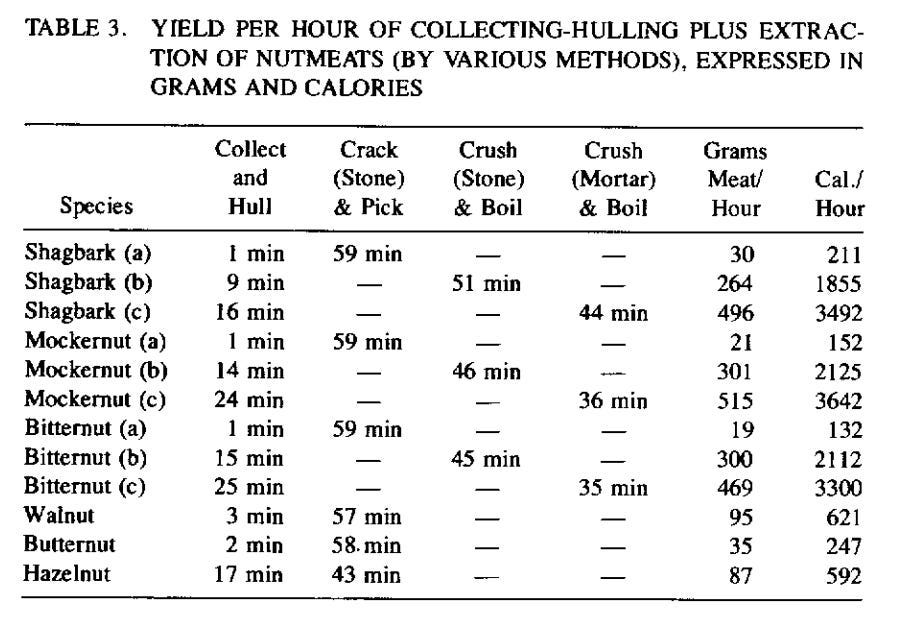

Much like discussed in our other nut pieces, sites with high amounts of butternuts also had large subterranean storage pits, where butternuts were likely stored over years, due to masting patterns with large crops every three years or so. This brings us once again to the question of caloric return for processing.

The above graphic is misleading— as you can see, they highlight the grams of meat per hour from the butternut as only 247 based on cracking & picking, which wasn’t the way butternuts were consumed, based on the first-hand accounts we covered before. Because of that, we can estimate that butternut is likely somewhere in that 3000 range of calories per hour through boiling, and given its high protein and fat content, it likely produces more oil and a higher quality calorie in comparison to hickory!

Butternut Canker

Butternut canker was first reported in Wisconsin in 1967, but as we said, was likely present in North American forests for decades.16 The fungus responsible for the disease spreads primarily by rain-splash (which is exactly as it sounds), but insects and birds can also be vectors, which explains how butternuts that are isolated become infected. The cankers primarily occur at the base of the tree, and eventually girdle and kill the tree rather quickly.17 While never a particularly common tree on the landscape, except in the orchards managed by indigenous tribes, the past seven decades have put the species in rapid decline. From 1966 to 1986, there was a 77% reduction in butternut populations, with some states reporting over 80% losses.18 From the 1980s to 2015, population dropped again by another 58%. At least ten states at this point have included butternut as a species of special concern, threatened, or vulnerable— including Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Ohio, Tennessee, New York, Minnesota, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

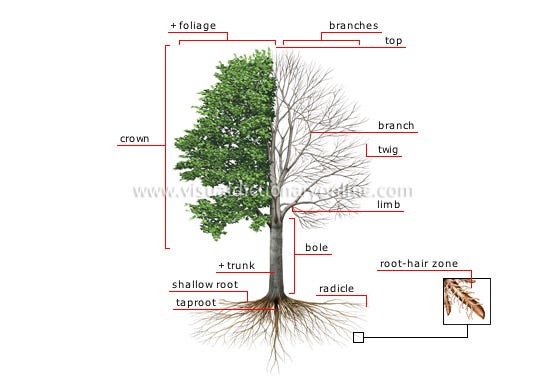

The infection itself is at first a slow process— the conidia get access into the tree through branches in the lower crown, which may have some weaknesses from leaf scars, wounds, cracks in the bark, and so on. Cankers then form on the infected twigs. The fruiting bodies of the fungus rupture the bark of the branches. As rain hits the branches, the conidia drip down the tree to the trunk and root caller region where they infect the inner bark. The trunk cankers eventually cause tree mortality as they begin to surround the bottom of the trunk, and eventually girdle the entire tree.

Butternut canker doesn’t affect butternut of a particular age or size— they will infect any butternut tree they come into touch with.

The future of the butter-buart-butter-butter-butternut

Earlier we had discussed that the butternut hybridizes with Japanese and English Walnuts. While they will create viable seeds with English walnuts, their offspring produce very few fruits.19 Japanese hybridize easily with the butternut and a horticultural variety of Japanese walnut, the heartnut, is often used to create what is called the buart (or sometimes butterjaps and buartnuts). The nuts that are produced often look similar to butternut. Unlike the English hybrids, the buart produces immense fruit and can cross with other hybrids, both parental species, and there’s evidence that they may even self-pollinate.

Now, for folks familiar with the story and the breeding work being done with the American Chestnut, this should sound all very familiar. The implications of these hybrids are obvious— that we may make the native butternut extinct as it is outcompeted by the hybrids— but also, the hybrids may be the only way to save the butternut, given all of the other ecological challenges we face. As DNA-based markers from parental species are better documented, we are developing better tools to identify these hybrids from the native pure butternut. Because of the success of the Japanese walnuts as well as their descendant hybrids, in some places, they are now considered invasive. Japenese walnuts have also hybridized with black walnuts as well and could begin to impact the long-term viability of the black walnut’s native genetics.20

Some breeders are actively working to reduce the amount of heartnut genetics in these hybrids, back-crossing the buart with butternut again, which have been called butter-buarts.

Identifying trees with seed worth propagating can be an intimidating practice— Michael Ostry, arguably the world’s foremost expert on butternut, suggests that trees worth sourcing seed from should show more than 70% live crown and less than 20% of the combined circumference of the bole and root flares affected by cankers and that all trees with at least 50% live crown and no cankers on the bole or root flares. He also recommends, when evaluating, to consider only limbs in the upper and out portion of the crown, as the interior and lower branches may have died from shading.

It’s important to understand that the reason butternuts can thrive at such sparse populations is that they are capable of pollinating one another at a distance of over a mile, so even a relatively small butternut population can provide immense genetic diversity.21 It also points out the challenges of attempting to control the spread of hybrids at this current juncture. That said, finding clusters of forest-grown butternut not near former home sites is most likely to produce pure butternut seeds. Like black walnuts, the best way to gather the seeds is when half of the fruit has fallen off the tree. Shaking the tree, if possible, to loosen fruit will help reduce the risk of weevil-infested nuts. Unlike black walnuts, it’s not recommended to drive over the nuts to break the husk off the tree— butternut shells are not as strong as black walnuts and you will likely destroy the nuts.

Now, there have been butternut that have been resistant to canker, and seeds have been harvested to propagate these particular trees. These trees, based on analysis done by researchers, tend to be trees that are in open areas or are dominant trees within the forest. Further cooler climates showed stronger resistance to canker, giving us an idea of what conditions will best protect these trees in the future.22 Another factor that has been shown to determine the likelihood of survival is to keep trees on drier sites, away from the traditional, wetter regions where these trees historically existed.23 Regardless, rates of infection are over 90%, meaning that finding a fully native butternut without canker is exceptionally rare.24 The Forest Gene Conservation Association in Canada has been grafting and planting these resistant trees across Ontario and is actively being monitored for canker infection. Some of these grafts have already produced nuts, which are planted in orchards and being monitored.25

In 2019, geneticists from the United States and Canada met at Purdue University to discuss resistance breeding for butternut. From this effort, a breeding plan was developed using confirmed hybrids with confirmed butternut to backcross to the hybrid trees. This is the same selection method done with American chestnut, which has created a genome with greater than 90% C. americana. This breeding plan would conserve maternal lineages in the short term and buy us time until other advances are made to help researchers create a new plan.

If you’re interested in looking for native butternut, use this guide from Purdue to help you increase your likelihood of property-identifying trees, however, they cannot be 100% confirmed without genetic testing!

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 12-page chapter, of (so far) a 916-page book with 589 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this episode, #192, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. Suppose you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content. In that case, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

https://natural-resources.canada.ca/our-natural-resources/forests/wildland-fires-insects-disturbances/top-forest-insects-and-diseases-canada/butternut-canker/13375

Ostry, M.E. and Moore, M. 2007. “Natural and experimental host range of Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum.” Plant Dis 91:581-584

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/juglans/cinerea.htm#:~:text=Native%20Range&text=It%20grows%20in%20Wisconsin%2C%20Michigan,far%20south%20as%20black%20walnut.

Farrar, J. L. Trees in Canada. Fitzhenry & Whiteside LImited, Markham, ON, Canada, and Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Services, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Burns, R. M., & Honkala, B. H. (1990). Silvics of North America. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service u.a.

Guzman-Torres, C. R., Trybulec, E., LeVasseur, H., Akella, H., Amee, M., Strickland, E., Pauloski, N., Williams, M., Romero-Severson, J., Hoban, S., Woeste, K., Pike, C. C., Fetter, K. C., Webster, C. N., Neitzey, M. L., O’Neill, R. J., & Wegrzyn, J. L. (2023). Conserving a Threatened North American Walnut: A Chromosome-Scale Reference Genome for Butternut (Juglans Cinerea). https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.12.539246

Ostry, M. E., & Pijut, P. M. (2000). Butternut: An underused resource in North America. HortTechnology, 10(2), 302–306. https://doi.org/10.21273/horttech.10.2.302

Goodell, Edward. “Walnuts for the Northeast” https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/52562792#page/19/mode/1up

Finkelstein, S. A., K. Gajewski, and A. E. Viau. 2006. “Improved Resolution of Pollen Taxonomy Allows Better Biogeographical Interpretation of Post-Glacial Forest Development: Analyses from the North American Pollen Database.” Journal of Ecology 94 (2): 415–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01087.x.

Wykoff, M. W. 1991. Black walnut on Iroquoian landscapes. Northeast Indian Quarterly 8:4-17.

Talalay, Laurie, Donald R. Keller, and Patrick J. Munson. 1984. “Hickory Nuts,

Walnuts, Butternuts, and Hazelnuts: Observations and Experiments Relevant to Their Aboriginal Exploitation in Eastern North America.” In Experiments and Observations on Aboriginal Wild Food Utilization in Eastern North America, edited by Patrick Munson. Vol. 2. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society.

Bosco, S. L., & Pritts, M. (n.d.). The past, present, and future importance of temperate nut trees to Haudenosaunee food sovereignty and climate smart agriculture in New York State (dissertation).

Yarnell, Richard A. 1984. “The McIntyre Site: Late Archaic Plant Remains from

Southern Ontario.” In The McIntyre Site: Archaeological, Subsistence, and Environment, edited by Richard Johnston, 87–112. National Museums of Canada.

Johnson, Elias. 2006. “Legends, Traditions, and Laws of the Iroquois, or Six Nations,

and History of the Tuscarora Indians.” Legends, Traditions, & Laws of the Iroquois, or Six Nations, & History of the Tuscarora Indians, 119.

Hart, J. P., & Rieth, C. B. (2002). Northeast subsistence-settlement change, A.D. 700-1300. New York State Museum, New York State Education Department.

Renlund, D.W. (Comp., Ed.). 1971. Forest pest conditions in Wisconsin. P. 26–28 in Annual report 1971. Wisconsin Dept. of Nat. Res., Madison, WI. 53 p.

Tisserat, N., and J.E. Kuntz. 1983. Longevity of conidia of Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum in a simulated airborne state. Phytopathology 73(12):1628–1631.

Ostry, M.E., Mielke M.E., and D.D. Skilling. 1994. Butternut—strategies for managing a threatened tree. USDA Forest Service Gen Tech Rep. NC-165, North Central Forest Experiment Station, St. Paul, MN.

Woeste, K., Farlee, L., Ostry, M., McKenna, J., & Weeks, S. (2009). A forest manager’s Guide to Butternut. Northern Journal of Applied Forestry, 26(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/njaf/26.1.9

Mooney, H.A., and E.E. Cleland. 2001. The evolutionary impact of invasive species. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5446–5451.

Ross-Davis, A., M.E. Ostry, and K. Woeste. 2008. Genetic diversity of butternut (Juglans cinerea) and implications for conservation. Can. J. For. Res. 38(4):899–907.

Sambaraju, K. R., DesRochers, P., & Rioux, D. (2018). Factors influencing the regional dynamics of butternut canker. Plant Disease, 102(4), 743–752. https://doi.org/10.1094/pdis-08-17-1149-re

Moore, M.J., M.E. Ostry, A.D. Hegeman, and A.C. Martin. 2015. Inhibition of Ophiognomonia clavigignentijuglandacearum by Juglans species bark extracts. Plant Dis. 99(3):401–408.

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). 2017. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the butternut Juglans cinerea in Canada. COSEWIC, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Pike, C. C., Williams, M., Brennan, A., Woeste, K., Jacobs, J., Hoban, S., Moore, M., & Romero-Severson, J. (2020). Save our species: A blueprint for restoring butternut (juglans cinerea) across eastern North America. Journal of Forestry, 119(2), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/jofore/fvaa053