The permaculture movement has captured the attention of most folks who find themselves looking for sustainable alternatives to ‘conventional’ agriculture. Part of this attraction comes from its broad-strokes ‘ethics’, which leave much interpretation to the end-user, as well as its capacity to absorb other concepts into this broad ‘systems' concept. Organics, biodynamics, no-till, regenerative grazing, perennial agriculture, agroecology— while they may not define themselves as permaculture practices, permaculture defines them as permaculture practices. This allows for the movement to flourish, pulling in anyone outside of the conventional agriculture zeitgeist.

For us to understand how and why the permaculture movement has grown into what it is (for better or worse), we have to understand how it got there. To do that, we have to understand its founders and the work that influenced them. It means we need to understand the history of David Holmgren, Bill Mollison, and the entirety of the permanent agriculture movement up to the 70s (which we have, to this point, documented extensively).

Bill Mollison

Born in 1928 in the fishing village of Stanley, on the north-west coast of Tasmania, Bill (whose given name was Bruce), was the son of Roland Mollison and his wife, Amy (Harmon). His parents ran a butter factory and later built the village bakehouse that Bill took over at the age of 14 when his father died, delivering bread on horse.1

Leaving home in his teens (after calling his mother a bully), he found himself working as a fisherman to keep himself fed. In his 20s, he also worked as a seaman, mill-worker, driver, forester and trapper. He understood and celebrated the self-reliance of rural life in the 1940s, and his love of the natural world led him to join the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in 1954, working in agricultural research for 10 years before leaving to study biogeography, the study of the distribution of plants and animals, at Hobart University.

Before that, in the 1940s, he flew Tiger Moths in the air training corps (his father, Rowland, had been one of the gunners who shot at Baron von Richtofen the day a single bullet killed the German flying ace of the Great War).

In his autobiography ‘Travels in Dreams’, Bill Mollison traced his realization that humans could 'copy' natural systems back to 1959, to what he regards as the generative thought behind permaculture. He recalls that, while observing marsupial browsers in the Tasmanian rainforest, he wrote in his diary that “I believe that we could build systems that would function as well as this one does.”2 An interview with Scott London backs this understanding as the origins of his permaculture concept:

It actually goes back to 1959. I was in the Tasmanian rain forest studying the interaction between browsing marsupials and forest regeneration. We weren’t having a lot of success regenerating forests with a big marsupial population. So I created a simple system with 23 woody plant species, of which only four were dominant, and only two real browsing marsupials. It was a very flexible system based on the interactions of components, not types of species. It occurred to me one evening that we could build systems that worked better than that one.

That was a remarkable revelation. Ever so often in your life — perhaps once a decade — you have a revelation. If you are an aborigine, that defines your age. You only have a revelation once every age, no matter what your chronological age. If you’re lucky, you have three good revelations in a lifetime.

Because I was an educator, I realized that if I didn’t teach it, it wouldn’t go anywhere. So I started to develop design instructions based on passive knowledge and I wrote a book about it called Permaculture One. To my horror, everybody was interested in it. [Laughs] I got thousands of letters saying, "You’ve articulated something that I’ve had in my mind for years," and "You’ve put something into my hands which I can use."3

During the 1950s, he largely lived alone as he continued to trap, hunt, and work as a lumberjack. He has described this time as a period when he was in a close neighborly relationship with the aboriginal peoples of the Australian bush, who taught him about living in harmony with nature.4 As the 50s continued on and developers began to destroy the landscape around him, he decided his best efforts to stop the encroachment was to actively participate in the environmental policy of the country by going into research and academic teaching.

By the 1960s, he was a pipe-smoking radical. A trained psychologist, he graduated from university in his mid-40s, in the late 1960s, and shortly after he was appointed a lecturer at Hobart in 1968, and some years later developed a new discipline, environmental psychology. At this stage, he could have settled into a comfortable academic life.

Not to let things seem to simple, he ran for Parliament alongside Bob Brown in the 1970s with the United Tasmania Group, a party regarded as a forerunner to the Greens. In Bill’s words, however, "I got out of politics because all I want to do is green the earth and I've chosen to do that in different ways." During this same time, he marched against the Vietnam War. As a CSIRO researcher, he proved that foresters did not need to lay poison to stop wallabies from grazing regrowth forests based on the studies he had done which had also inspired permaculture. He also helped fund Aboriginal scholarships by selling wallaby skins, while also becoming a foundation member of the Organic Farming and Gardening Society in Tasmania with Cundall in 1972. 5 He pushed back against the destruction of the ecosystems around him, and it was during a campaign against the dam on the Franklin River in Tasmania that he would later meet David Holmgren.

David Holmgren

Holmgren has described his childhood as having two parts— when his parents towed the Marxist party line and when they did not. The challenge of having open and progressive parents was that it was difficult to be rebellious; that there was little to rebel against. After graduating from John Curtin Senior High School in 1972, he took a year to hitchhike the country, searching for purpose, before moving to Tasmania in 1974 to study environmental & landscape design.

Part of his draw to the Tasmania Environmental Design School was the lead architect and education, Barry McNeil, who was according to Holmgren, “The most radical experiment in tertiary education in Australia."6 The school had no fixed curriculum, there was a self-assessment process at the end of each semester, which then led to a major study at the end of the three-year degree. This final project was then reviewed by outside professionals for final approval and graduation.

During this period, David was exploring— as part of his research in school— various methods of self-sufficiency, all of which would contribute later on to his book Retrosuburbia. He was also concurrently busy as an activist, working to stop high rise development in the historical Battery Point precinct and working alongside a number of radicals.7

The early 70s was a period of grand experimentation in landscape architecture, as folks like Ian McHarg was gaining prominance, and EF Schumacher’s book Small is Beautiful had recently hit the shelves, where the term “appropriate technology” was first coined. While change was afoot, in David’s words, “there was no clear didactic direction. The whole thing was a chaotic exploration.”

The beginnings of permaculture’s landscape design was beginning to form. David describes trying to tie agroecology, organics, and landscape design into one narrative, that “agroecology, for example, didn’t seemt o have much of a design focus… [that] there was some crossover between landscape architecture & agriculture but really as cosmetic design overlay in some particular affluent parts.” He felt shortfalls in the organics and agroecology movements would help form permaculture.

Permaculture

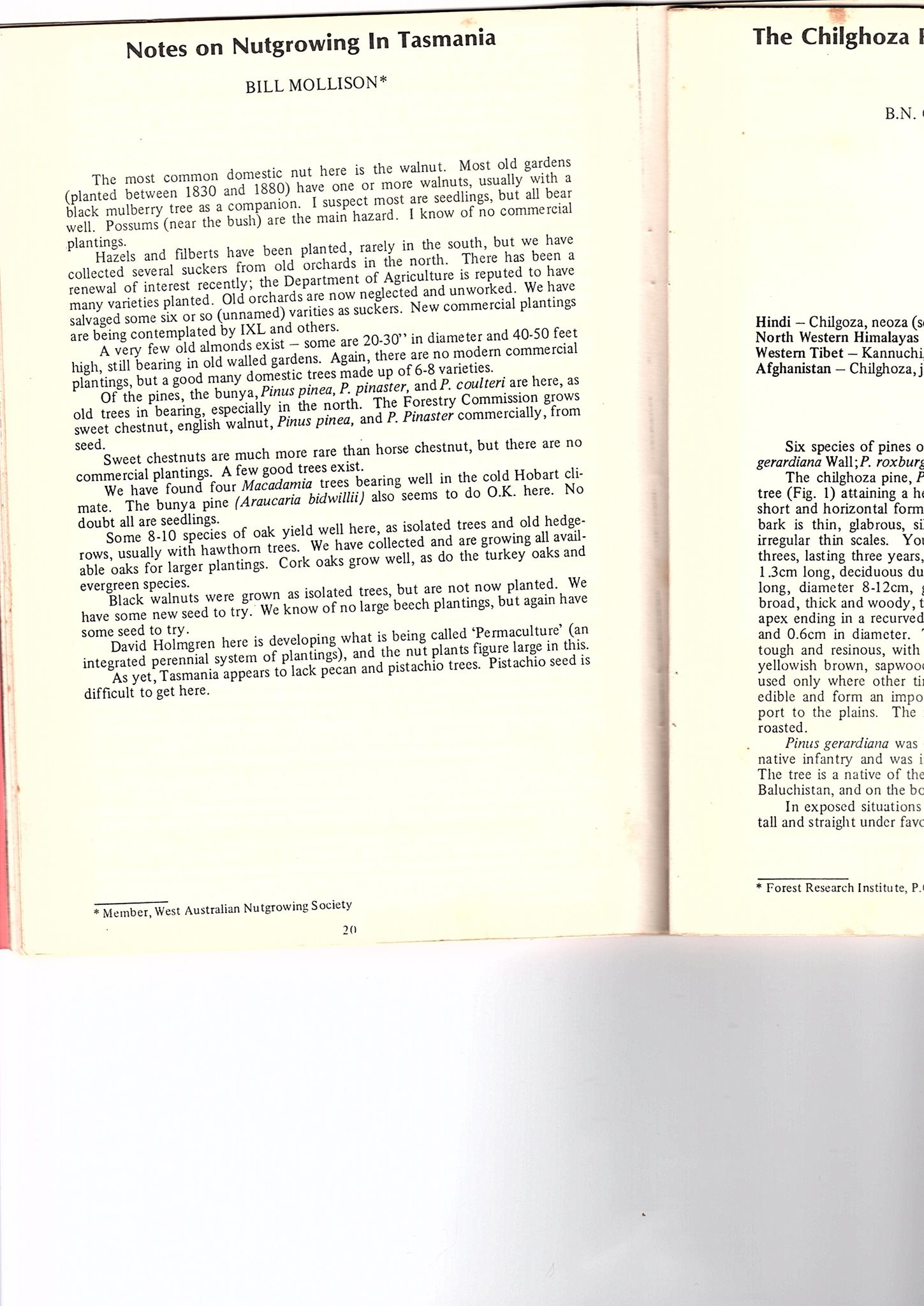

David Holmgren was a student as Bill Mollison began the journey into what is now called permaculture, starting in 1974 and leading to the portmanteau of ‘permaculture’ in 1975. The date often seen in histories of the words permaculture is 1976/7, but a short essay on nuts by Bill Mollison in 1975 appears to be the first time the terminology has been documented.8

David explains that the birth of Permaculture came from a discussion with Bill about his research; David explained his frustration with landscape design, agroecology, and organic agriculture, to which Mollison responded that David should focus on answering the design question of how natural systems designs forests and other ecosystem. It also raised the question of why humans, in David’s words, “don’t appear to be using that in our prime activity on the planet, agriculture by which we feed ourselves.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Poor Prole's Almanac: Restoration Agroecology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.