If you’ve been following our series on permanent agriculture, we’ve gone in extensive depth on the evolution of soil science to permanent agriculture to the Odum brothers’ vision for agroecology. While their work stemmed from the science-led movement of permanent agriculture as the permanent agriculture movement crashed under the pressures of World War 2, multiple concurrent movements followed. The first we covered was the Odum Brothers and their vision of agriculture driven by ecological limitations. An openly, self-proclaimed less scientific vision came under the organic movement, as well as the biodynamic movement, and the Back to the Land movement, and many of these advocates go on to coalesce under the permaculture movement. But before we can understand how those created the newer movement of homesteading and permaculture of today, we need to understand how and why the organic movement thrived in the early days after World War 2.

In the previous pieces on permanent agriculture, we explored the need for ecological thought to become entrenched with agronomy, and how this process had begun in the early 1940s. One particular advocate for this change was a British botanist, Sir Albert Howard. In 1903, he went to India as a professor to teach how to grow food in India. However, during his time there, he realized they had better techniques, specifically around composting, and he began to write about their techniques for a global audience. He was also one of the primary advocates for the study of ecology and the need to incorporate ecology into food systems. He was an ardent supporter of the permanent agriculture movement spreading across the United States.

Organic Origins

While the voices we mentioned in the previous episode were focused primarily on big-picture, systems thinking, folks like Sir Alfred Howard, his wife Gabrielle Howard, South Africa’s J.P.J. Van Vuren, and Austria’s Rudolf Steiner & Ehrenfried Pfeiffer were focused on what it looked like to rebuild the soil. Van Vuren argued that soil erosion was specifically from a “specific disease of the soil, caused mainly by a humus deficiency.”1 The organic movement was framed in the same argument of seeing the topsoil and the corresponding crops about the ecology surrounding them. These practices developed or discovered by the West are still in practice today, including things like incorporating composts, green manures, and even humanure practices. The claims made by these advocates were bold, that crops would be disease and pest-resistant and pass these qualities to humans who ate organically produced food.

Even before arriving in the United States, the organic movement experienced a clear division— those who wished to prove that organic was better for humans and the landscape through experimentation and studies, and those who believed organic was akin to a spirituality which brought its adherents closer to God and his vision.2 Researcher Philip Conford described the early European organic advocates, stating:

Their opposition to industrial agriculture was rooted in a belief in a natural order whose limits could not be exceeded with impunity… The organic criticism of orthodoxy was essentially prophetic: it predicted problems and ultimate disaster for any agricultural system which flew in the face of the natural order, it read the signs of the times and called for a return to God’s ways.3

Despite the birth of the movement coming from Howard watching indigenous farmers of India, the organic movement developed a social position of nativism in which native soil health reflected the strength of a race. Organics challenged an international commerce system that took power away from communities and was a means to return to an agrarian social foundation and quickly became the basis for fascist-leaning “blood and soil” groups. Progressive Christians found similar benefits to the organic movement, as they were often skeptical of industrialization and the increasing power of urban-based financial institutions at the expense of the often more religious countryside. From either of these perspectives— the undercurrent was the same— autonomy for rural communities was necessary for a natural order to remain— whether that was based on God, the hierarchy of races, or both.

In Great Britain, Jorian Jenks was considered one of the primary figures in the organics movement. While Jenks was a primary leader in the biggest organics journals in the country, he was also an active member of the British Union of Fascists. Jenks wrote for the Fascist Quarterly and advocated that agriculture, not money, should be the basis of our economy and wealth measurement.

Many other leaders of the organics movement worked in lockstep with Jenks— Henry Williamson, Oswald Mosley, Viscount Lymington (whom we discussed in the Biodynamics piece), the Duke of Gaultshire, all of which tied anti-semitism, a de-financialised economy, and organic husbandry into one cohesive narrative: Restoration of rural spaces with the application of natural methods. P.C. Loftus, for example, argued that part of the issue with Britain was due because of the decline in the quality of b

read. Whole, organic foods were necessary for “racial reinvigoration”.

Even folks who didn’t align openly with fascism found themselves contributing to far-right organics journals such as the New Pioneer, including Sir Arthur Howard, the father of organic farming. In many ways, the organics movement was simply another extension of fascism that leaked into our kinship with the Earth around us.

So what changed? The Guild Movement.

As the early 20th century progressed, an increasing resistance to industrialism grew. Many socialists found themselves identifying the same issues of society as the fascists they despised— specifically the financial systems and increasing reliance on mechanization. In response, many socialists found themselves looking to restore skilled union guilds as tools to push back against industrialization. While the center-left Labor movement refused to engage with the issue of finance driving speculation, scaling, and the removal of skilled labor in the economy, the right did not, and many people were driven to the right or found themselves searching for something else.

The Economic Reform Club and Institute would step in to fill this voice, and would be key in coalescing the organics movement away from outright fascism. The group’s intent was very simple— to better understand the workings of the monetary system. By 1939, both major right-wing figures in the organics movement such as Viscount Lymington as well as noted socialists found themselves together, urging for a food policy based on human needs instead of financial gains, driving attention to health and food quality, among other issues. The organization’s agricultural bulletin was edited by Jorian Jenks, and they would argue that healthy food at an affordable price was a right of every citizen— a position that was supported across both the left and far-right.

While the Institute wouldn’t produce meaningful change in Great Britain, it did slow the momentum of fascism in organics.

After World War 2, Jenks continued to write and influence the organic movement heavily. He traveled to the United States and spoke at the United States Conference on Food and Soil. While open fascism was no longer acceptable as it had once been, the same names continued to be printed in new magazines. Many of the writers traded in racial heirarchy and purity for Christianity and the Divine— what it termed “Christian sociology”— functionally, it was simply nationalism in new dressing. We’ll explore how the Christian sentiment behind organics reinforced some of the darker paths of the organics movement in the following homesteader article.

Organics in the United States

The split between the organic & biodynamic movement— the latter which we’ve covered recently– and the permanent agriculture movement began in 1943, with the publishing of Edward Faulkner’s book “Plowman’s Folly”, which outlined trash farming. The first criticism of this practice was from the USDA’s Soil Conservation Services, led by Hugh Bennett, a major advocate for permanent agriculture. While other critics would point to Faulkner using data from a small, individual plot with a handful of crops and suggesting that we could extrapolate new policy based on this small sample size, Bennett and the SCS instead pointed to the fact that soil fertility was not as simple as simply plowing plant waste into the soil, that if all it took to create soil health was the return of the nutrients that created plants, all of the forests on the east coast would have rich, healthy soils, instead of the “poor”, acidic soils so common even in old forests, where the leaves return to the soil, season after season. The reality was that this division between these similar, but different movements began to form between advocates of permanent agriculture which was framed in science first— even the very imperfect science as it existed, and advocates who looked towards the broad strokes of how nature operated first and relied on naturalist fallacies.

Faulkner was a county agent who advocated for permanent agriculture solutions and eventually ended up in Ohio after being pushed out of the Extension program he was associated with. He took a job and dedicated all of his free time to figuring out how to grow food with the soil, ultimately concluding that the moldboard plow was the reason for topsoil destruction. He cited the loss of water absorption, and the limitation of plant growth after a season of plowing, and instead began implementing what he called trash farming.

Trash farming today is best known as mulching— specifically with plant residues. The concept of conservation in tillage was widely understood as far back as the middle 19th century, but his work brought it back to light again. Organic farming, at this time, had continued to include spading and rototilling barnyard wastes, composts, and mulches; the trash farmer would stir in green manures using a disc plow instead of burying the material underneath the surface layer. The result was a topsoil with residue just barely below the soil which in his words was “restoring the conditions which prevailed upon the land when it was new, [and which] will cure erosion and restore productiveness in a single stroke”. He claimed that trash farming would increase productivity 5x that of petrochemical fertilizers, a dubious claim at best, and one which today we know not to be the case.4

Meanwhile, under the wave of permanent agriculture and petrochemical fertilizers taking up much of the space in agriculture magazines, William Albrecht, at the University of Missouri quietly reported on the discovery of beneficial bacteria for beans and pea plants in 1918, which helped them acquire nitrogen from the air. Until 1974 he would publish about organic soil management, largely underappreciated and despite providing a foundational component of organic agriculture science, he was also highly critical of what he called the “organic cult”. His criticism kept him from being published in Rodale’s magazines, despite being a leading figure in soil science through the 20th century with many similar beliefs about the current state of agriculture.5

If it hasn’t been made clear, a major part of the split between organics, biodynamic, and permanent agriculture was based on their relationships to the scientific method. This was accelerated by widescale acceptance from researchers, politicians, and USDA officials around the goals of permanent agriculture— which to them was simply a focus on healthier soil. In this process, however, the term permanent agriculture became less about permanent crops and more about branding, whether it was John Deere building equipment for what was considered to be agriculture that catered to soil health, or toothless language which was summarized in P.V. Cardon’s essay, “A Permanent Agriculture”, which defined it as:

Agriculture that is stable and secure for farm and farmer, consistent in prices and earnings; agriculture that can satisfy indefinitely all our needs of food, fiber and shelter in keeping with the living standards set. Everybody has a stake in permanent agriculture.

The term had become ambiguous and meaningless, greenwashed and ultimately unsalvagable by the 1950s. In contrast, the organic and biodynamic movement continued to grow alongside the increasing atomization of the post-World War 2 era under increasingly hostile leadership to any alternatives.

If the wholesale blacklisting of Albrecht hasn’t made it clear, some characters boldly pushed the envelope around the benefits of organic agriculture. Names like J.I. Rodale advocated for increasingly unrealistic benefits of organics, while also pushing wildly unscientific machines, including a chair he kept in his home that “gives off short wave radio waves… and boosts his body’s supply of electricity.” He believed that “people don’t get enough electricity from the atmosphere or earth anymore because of steel girders overhead and insulation underfoot.”6 This wasn’t the only example of oddities that became intertwined with the organic movement, but is a clear example of where the hard sciences that defined the permanent agriculture movement bled away on the fringes.7

What might stand out at this point is that many of the advocates, outside of Rodale, who was effectively a businessman who made health foods his business, we haven’t mentioned many Americans. Even Rachel Carson, a focal figure in the explosion of the organic movement from her writing, chose not to be identified as part of the organic movement. This repeated paradox highlights the lack of scientific backing the movement had and its willingness to engage with unscientific ideas.

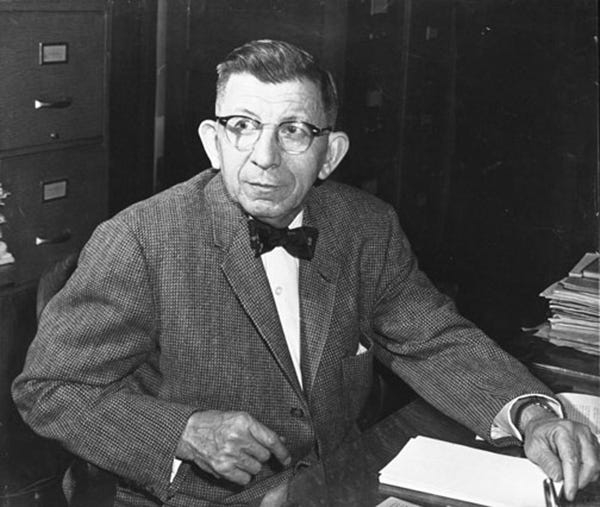

Now, Rodale was the nexus for the movement within the United States. Rodale’s early life was filled with health-related issues from growing up in the polluted city of Pittsburgh, and the work of Faulkner and Howard inspired him to learn more about the association between health and the environment.

Born Jerome Irving Cohen in 1898, Jerome was the child of Eastern European immigrants and he was most interested in becoming a writer, despite his parent’s attempts to see him become a rabbi. Judaism remained an important part of his life, and he donated heavily to Israel. In the 1930s, he heard Robert McCarrison lecture in Pittsburg on “Faulty Foods”, which stuck with him. He found himself years later working as a publisher, producing Health Digest, among other journals. In one of these health magazines, he stumbled across Sir Albert Howard’s work and become obsessed, writing to Howard and eventually becoming close friends.

He decided to move out of the city and to a farm in Emmaus, Pennsylvania in 1940 and in 1942 launched the publication Organic Farming and Gardening. He also formed the Soil & Health Foundation (later the Rodale Institute) to support organic research, which would be the backbone for the science behind the organic ideology in the United States. By 1949, the magazine had reached 100,000 copies in circulation. 8 During this same time, Rodale founded the Soil & Health Foundation to study organic practices, but Rodale found the work to move too slowly.

As his various magazines grew in popularity, he used them as a pulpit, criticizing arsenic sprays and DDT and additives in food. His notoriety continued to grow— in his words, “I am suddenly becoming a prophet here on earth and a prophet with profits.” Unlike the criticisms of capitalism and the levers of power that destroyed social society that the biodynamic movement recognized, Rodale instead ignored these entirely, and focused on self-improvement, individual body purity, and setting the stage for the environmental health marketplace that gave birth to Whole Foods and the like.9

He continued to write plays, and when critics were unkind, he would take out entire page ads to attack the critics— that they could not see past the man, whom they despised— any criticism of his work was because of his radical food beliefs.

In 1971, Jerome Rodale passed away on camera for the Dick Cavett Show shortly after advocating for asparagus boiled in urine and announcing he would live until 100 (the episode was never aired, but there are a number of accounts you can read about the incident).10 The torch was picked up by his son Robert, who continued to grow the company to the point of having 200 million in revenue at the time of his unexpected death in a car accident in 1990.

Like many areas of study, the margins of permanent agriculture became increasingly filled with less scientifically-based proposals, often proposed by men looking to carve out a space between their genuine interests in restoring a relationship with the earth with a general lack of scientific knowledge. Seeing the Rodale’s incredible financial success also brought out the worst traits in many of these folks. Individuals like Louis Bromfield— previously mentioned for his project Malabar Farm, which was a financial catastrophe, E.B. White— yes, the one who wrote Charlotte’s Webb— as well as many others, waxed poetic regarding the picaresque image of the small homesteader or farmstead, often remarking that the homestead was part of a long American tradition, stemming from Jeffersonian, romantic views of what it means to produce food. Coincidentally, despite the fundamental disagreement around homesteading as a viable path for agriculture at scale, both White and Bromfield were prominent voices in Russell Lord’s quarterly magazine The Land.

The growth of this romanticized Back to the Land, while understandable, was not wholly supported by advocates of the permanent farming community. Rexford Tugwell, the prominent voice for permanent agriculture as public policy during the FDR administration, openly mocked the Back to the Earth movement but understood the deep desire to reconnect with the land and to be part of that restoration. This was an ironic position for Tugwell, given his role in attempting to build homesteading communities. That said, he understood that much of the promises made by mercurial writers like Bromfield promised goods that permanent nor organic agriculture could deliver; Faulkner had proclaimed that trash farming would put petrochemicals out of business and American farmers would lead the world in food production from his simple methods.

The organic movement continued to slowly create its niche as permanent agriculture fell into public purgatory. When the countercultural revolution of the 1960s took hold, organic farming greeted it. As young baby boomers explored the concepts of communalism, social ecology, and visions of agrarian revival, organic farming was front and center of that movement. Organic was more than organic, it operated concurrently with the concepts of renewable energy, appropriate technology, agroecology, and biodynamics. Further, population growth and fears of overpopulation became more popular in alternative agriculture communities, which was driven by the scientific framework the organic movement leaned on from the Odum brothers.

Ultimately, the counterculture trusted little from governments or corporations, and this was canonized in Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, which came to define the state of agriculture in 1962. In her book, she articulated cogently the precise issues of mechanized, chemically intensive, production-oriented agriculture. It’s no surprise then, when the Green Revolution— that is the post-World War 2 boom in agricultural petrochemicals, salt-based fertilizers, increasing mechanization, and plant breeding was proving to provide little long-term success both at home and overseas, people across the globe, from Mexico to India to Africa to our own breadbasket, people pushed back.

Despite attempts to sell its successes overseas, The Green Revolution’s critics viciously attacked it at home. John Todd, a marine biologist and founder of an alternative-technology company, in 1971 called the green revolution the “Agricultural equivalent of the Titanic, only this time there are several billion passengers”. The hyperbole of his condemnation was not uncommon in debates about the sustainability of contemporary agriculture. Needless to say, this helped give new life to some old concepts, and the Nearings were the ones who became the center of a new vision of holistic, organic, individualist living. We quickly brought up Scott Nearing when discussing Russell Lord’s work, but he was part of the voices advocating for permanent agriculture.

Much like Louis Bromfield, the Nearing’s solution to the world refusing to change was to buy a homestead in Vermont and show a different way of living; simpler, more ethical, and one that provided an alternative to industrial and corporate capitalism. His books were their primary source of income, and he wrote heavily about biodynamic farming, a form of holistic farming that engages with mysticism. The use of arbitrary soil management practices, for example, burying ground quartz and manure stuffed into the horn of a cow, is the primary differentiation between conventional integrated and organic farming and biodynamic farming.

We continue to see the development of this countercultural obsession with a new science with the development of John & Nancy Todd’s “The New Alchemy Institute”, which opened in 1970 to help people “learn good stewardship of the earth as they assist us in the development of new world skill and technologies”. Their goal was to develop technologies with minimal impact on the planet, but they’re most known for their work of trying to create self-contained, self-sufficient arks. It was this more extreme area of the organic and holistic agricultural movement that both drew in supporters and caused rejection from mainstream consumers. Various farmers attempted to make organic and biodynamic farming more palatable, from Robert Steffen, who managed thousands of acres in the 1970s with organic methods such as composting, and Garth Youngberg, who worked to help organize the organic movement and would later work for the USDA to tout alternative agriculture during Jimmy Carter’s presidency.

The movement to develop ethical food systems continued to grow, and much like immediately after the Second World War, the terminology of organic and sustainable food continued to be co-opted without any fundamental changes. The 1970s were considered to be one of the worst periods for topsoil health, being called the “great plow-up”, and topsoil health was worse in America than at any previous point. And in 1973 through 1979, the Energy Crisis hit.

The Energy Crisis brings memories of lines at the pump for consumers to get groceries, and houses being built with lower ceilings to conserve energy, but on the farm, the true costs of petrochemical fertilizers were more apparent than before. If the industry had been drunk on cheap growth, it was their reckoning. Further, the agriculture industry was ravaged by an economic crisis in farming; previous administrations had pushed farmers to tear out the hedgerows planted after the Dust Bowl with expectations that export markets would grow and expansion would not be cheap for farmers.

New, expensive equipment with high fuel and fertilizer costs meant farmers had to push out higher production– and they did. Within a decade, grain production increased by 20%. However, the global markets contracted, as production increased worldwide. The effects were immediate, and have been described as the worst economic crisis in rural America since the great depression. Additionally, the Federal Reserve increased interest rates from 1979 to 1984 by nearly 8%. As of this writing, in 2023, that is double what interest rates have increased during Biden’s tenure. Farmland values fell 63% in five years, and average net farm incomes in places like Iowa fell from $17,000 in 1981 to ($1,900) in 1983. In a previous piece, we saw how this played out with certain farmers, desperate for any miracle, being suckered into the Jerusalem Artichoke pyramid scheme with American Energy Farming Solutions and within that context, it is easy to understand how.

While the government had been involved in price manipulation for farmers since the Dust Bowl, it became pertinent that the government to keep the status quo acceptable to an increasingly uneasy public. Reagan’s administration quietly removed Garth Youngberg and any support for alternative agriculture, even removing research that had been legislated by the Carter administration. To support Reagan’s efforts, notable agricultural economists proclaimed that productivity increases meant that we needed to worry less about soil health, since “the nation could count on continued gains in crop and livestock productivity… the need to reduce soil erosion would be lessened since minor soil losses would be offset by technology,” as reported in the Des Moines Register.

It’s no surprise then that shaken farmers grasped for anything at hand— whether it was the sunchoke scam in the 80s or promises that organics would be more profitable with less work, a narrative that takes shape in both organics, permaculture, and regenerative circles. What underscored the organic movement from its inception through the present was a fundamental distrust in the systems of power that pervaded our food system. Whether it was the government’s fault or corporations, these two— from both left and right perspectives— were in bed with one another and focused on making our food quality poorer and profits higher for shareholders.

As the 70s and 80s rolled on, the organic movement faced a choice— become legitimate in the eyes of the government through formal certification processes, or continue to be led by men like the Rodale Institute, who ran a functional monopoly on the organic brand.

Today, as organics has been legitimized in the eyes of both the government and the general public, the question in organic circles is often about whether the movement has made more headway because of or despite state supervision. Leaving it in private hands is tenuous, regardless of politics— a handful of corporations have already begun greenwashing products under the guise of organics, and regenerative farming faces the same issue of the label reflecting a branding effect rather than a qualitative marker.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 22-page chapter, of (so far) a 1101-page book with 734 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #211, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Conford, P. (2001). The origins of the Organic Movement. Floris Books.

Obach, B. K. (2017). Organic struggle the movement of sustainable agriculture in the United States. MIT Press.

Conford, P., & Dimbleby, J. (2001). The origins of the Organic Movement. Floris.

Beeman, R. S., & Pritchard, J. A. (2001). A green and permanent land: Ecology and agriculture in the twentieth century. University Press of Kansas.

Ingram, M. (2007). Biology and Beyond: The Science of “Back to Nature” Farming in the United States. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 97(2), 298–312. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00537.x

The New York Times (1970) I can’t seem to find the exact link, but it was an old archive that doesn’t seem to be easily available anymore

Tucker, D. M. (1993). Kitchen gardening in America: A history. Iowa State Univ. Press.

Loomis, E. (2019). The Organic Profit: Rodale and the Making of Marketplace Environmentalism. Journal of American History, 106(1), 243–244. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaz294

https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/05/03/when-that-guy-died-on-my-show/