The History, Culture, and Agricultural Evolution of Blueberries and Huckleberries

Domestication in living memory

The blueberry has become ubiquitous across the world; its small, firm berries are enjoyed by young and old. The story of the blueberry, one of several vaccinium fruits, is far from simple, however. Vaccinium has a circumboreal distribution— meaning that it occupies the same space to the north pole across the planet (northern North America, Europe, Asia) but also has a handful of named species in the South Pacific Islands, South America, and Africa. Other vacciniums include huckleberries, cranberries, lingonberries, bilberries, and more. It was only in the past 100 years that blueberries weren’t just a small, seedy fruit relished by homesteaders and foragers but something available on shelves across the globe in a highly domesticated form.

Evidence of blueberry management in North America is over 10,000 years old, from indigenous people near Newberry Lake in central Oregon to eastern Massachusetts around the Pine Barrens of Cape Cod.1 Pollen analysis highlights that several fruits, including chokecherry, thimbleberry, raspberry, blackberry, and huckleberry were present and likely managed by native people as far back as 9,000 B.C across central Oregon.2

Historically, harvesting season was a communal effort. Harvest gatherings were times of celebration, sharing stories and passing on legends.3 They used special combs of wood or fish backbones to strip the berries off the bushes, which our modern blueberry rakes are fashioned off.4 In the Pacific Northwest, women or their families often “owned” the berry grounds, and the fields were often named after the trails connecting them. The berries were so honored that special people were selected for the first gathering of berries based on skill and knowledge of the plant, to the extent that it became a point of contention with early missionaries. It’s also worth noting that on the West Coast, the blueberry is also known as the huckleberry, which can be confusing, given that huckleberries (“True Huckleberries”) on the East Coast are not blueberries at all. References to ‘huckleberries’ from here forward are recognizing the traditional name for the blueberry on the west coast.

In 1615, Samuel de Champlain, the founder of French-occupied Quebec, was the first to record the Indigenous use of blueberries, observing Algonquin women as they dried “blues”, as he called them, in the sun. He noted that they prepared a bread of sifted cornmeal, boiled, mashed beans, and dried blueberries. The blueberries also provided “manna in winter” and Pemmican, a concoction of lean meat, fat, and blueberries or other fruit, a practice seen across much of northern North America. Roger Williams also noted the same, stating that:

Sautaash are these currants [blueberries or whortleberries] dried by the Natives, and so preserved all the year, which they beat to powder and mingle it with their parched meal, and make a delicious dish which they call Sautauthig, which is as sweet to them as plum or spice cake is to the English.5

Gabrial Sagard, a Franciscan friar, visited the Hurons in 1624 and wrote that:

There is so great a quantity of bluës, which the hurgon call Ohentaqué… that the savages regularly dry them for the winter, as we do prunes in the sun, and that services them for the comfits for the sick.

John Bartram also documented an Iroquois woman drying blueberries in 1743, stating that:

This was done by setting four forked sticks in the ground about three or four feet high then others across. Over them, the stalks of Centurea jacea [probably misidentified] or Saratula. On these lie the berries… Underneath she had kindled a smoky fire that her children were tending.6

Henry Thoreau took a special interest in blueberries, writing extensively, including an unpublished manuscript entitled “Wild Fruits”, which also contained more than twenty written citations on the Indigenous use of blueberries, where he concluded that:

…from time immemorial down to the present day, all over the northern part of America, (the Indigenous) have made far more extensive use of the whortleberry [blueberry] at all seasons and in various ways than we, and that they were far more important to them than to us.

Thoreau was so infatuated with blueberries that many of our sources today of Indigenous use are cited first in his unpublished manuscript.

While the Indigenous dried the fruits to enjoy throughout the year, colonists found canning to be an effective method for preserving the fruit, and by the end of the 19th century, picking would change both as a social practice and as a social meaning. Canning as a practice expanded extensively during the Civil War, and by 1875, industry improvements allowed the meatpacking industry to scale and expand its products west. While canned goods were difficult to transport and buy, the commercial canning industry allowed rural households to preserve what they could produce on-site. In 1888, the Ball Brothers Corporation upended the market by producing a fully automatic machine for making canning jars, cutting the price and making canning far more accessible for homesteaders.7

The Wild Blueberry Industry

Across Maine, the lush carpets of blue that cross the barrens had been harvested on burn cycles by residents since settlers had arrived, and the Indigenous for generations prior. Before the modern canning industry erupted, tin canning from the Civil War era had made blueberries easy to ship due to their proximity to bigger cities. By the 1860s, men were making “a snug fortune… from the product of these plains,” wrote a journalist at the Portland Daily Press.8

In 1870, William Freeman sued William Underwood, owner of a canning factory near his 70,000 acres, which he claimed covered nearly all the blueberry land in the region, for the theft of the blueberries from his fields. He argued that the harvesting destroyed his property and the prescribed burns removed any potential for timber harvesting and that the canners were liable for the taking of Freeman’s possession. The court sided with Freeman, which began a new system of leasing and payments that became the foundation of Maine’s blueberry industry.9

Landowners squeezed profits from canneries, and suddenly other industries wanted their share of the pie. The Maine state government canceled permits that allowed blueberry picking on public lands where other permit holders held timber or grass rights. Penalties were placed on trespassers of “improved blueberry ground”, marking a shift in foraging rights across the east coast.

In the 1880s, the blueberry rake was adopted. It was a modification of the cranberry rake, which increased production from— 1 to 3 bushels— without increasing wages. Despite the stories from newspapers of the profits made from a few day’s work of harvesting, the reality was much more grim.

On the West Coast, the story of the wild blueberry played out very differently. Not only were homesteaders canning fruit for their own consumption, but they were also spending weeks in the mountains to take berry-picking “working vacations”, particularly from 1900 through 1925. While homesteaders quickly filled up their buckets with sweet treats, Indigenous folks also continued to arrive at the fields to harvest berries as well.

By the early 1920s, commercial sales had begun in eastern Montana, where conveniently, two canneries had been built in the region to process apples and cherries. Wild huckleberries were an additional product they could process between the window of apple and cherry season, allowing for additional revenue, if they could find a market.10 They were a freely available fruit, grown and picked under the Forest Service’s free-use policy instead of on orchards. They preserved well and only required sugar for canning. In short, they were cheap, easy to work with, and ready to scale.

The biggest challenge was the terrain. Patches often grew on steep, northeastern slopes at alpine elevations, and throughout the berry season, temporary housing was needed to make the practice profitable for pickers and processors.

Now, despite what may appear as widespread wild blueberries in regions like the Pine Barrens, fields are disappearing as tree canopies have become thicker, due to a lack of prescribed burns across much of northern North America.11 Further, this is not a new phenomenon; and even colonial America understood the role of fire in blueberry management. Shaikut Nie, of the Yakama people, explained that the prescribed fires were crucial, that “This is what makes berries.. While our forefathers were here they took care of everything.”12

Despite the documentation and storytelling of fires in the West as a tool for huckleberry management, eastern lowbush blueberries respond even better than their western counterparts. Due to massive wildfires in the Great Burn of 1910, much of what had once been managed huckleberry acres had been recleared, and by 1928, extensive fields across the northern region of the Pacific Northwest were perfectly suited for the burgeoning industry. Further, new Forest Service roads were constructed after the Great Burn for fire prevention, making transportation to this new productive region of huckleberries feasible.

Something else came in 1928— the stock market collapse, and an entire new labor force who had picked the berries as a hobby for decades. According to A.H. Abbott, a district ranger on the Cabinet National Forest, the huckleberry industry exploded, and by 1933 the “value of huckleberries gathered on the Cabinet last year alone considerably exceeded the total grazing, special use and timber receipts for several years past… in excess of fifty thousand gallons.”13 Sources say that the fruit could sell for $0.40 a gallon, equal to $7 in 2024 dollars, providing a meaningful wage to people who otherwise could not find work.

Industry grew. Men like Clifford Weare & John McKay developed harvesting pickers and created cleaning techniques to scale up production based on Indigenous harvesters. Their success didn’t go unnoticed. In 1926, A. Holstein sent Weare a business proposition, to “give the laborers the best paying job they ever had and the merchants the best fruit they ever handled and still have something left for our trouble.”14

Commercial picking became such a strong force that encampments arrived during harvesting season. The picker technologies that continued to be improved and developed became a cultural icon for the regional identity. By the 1930s, the commercial huckleberry industry was the major national forest “free use” of the time— for better or worse.

The massive influx in harvesters caused the Forest Service personnel to worry about the potential fire hazards, sanitation, and other hazards from these massive transient communities. At first, the solution was to create enclosed regions for harvesting with latrines and garbage pits— regions that also separated Indigenous from White pickers.

As the 1930s neared its end, the commercial industry had become more established. Technologies allowed for increasing scale. Research had expanded around the domestication of the blueberry, including John Hershey’s early lost work with select blueberries.

The economy had begun to improve, and the United States began to gear up for World War 2. Gas rationing and wartime scarcities meant limited gas to access the wild patches and closed parks. After the war, the wild huckleberry industry fell off— families had stopped canning en masse as the infrastructure from the War and the post-war boom led to the supermarket and affordable freezers. Logging jobs had begun to return, with better pay. Those who remained to harvest were largely the Indigenous, who were kept out of the job market and had closer cultural ties to the huckleberry. Those who were not Indigenous fell into two camps; people looking for a little extra money, and folks in difficult circumstances who struggled to hold “regular jobs”, a consistent characteristic of the industry even today.

Domestication

Across the nation and decades prior, in 1893, a logging contractor named Moses A. Sapp was quietly breeding rabbiteye blueberries on his farm in Florida.15 While his work started a boom in the southeast, the industry faded by the early 20th century and he has been largely forgotten in blueberry history.

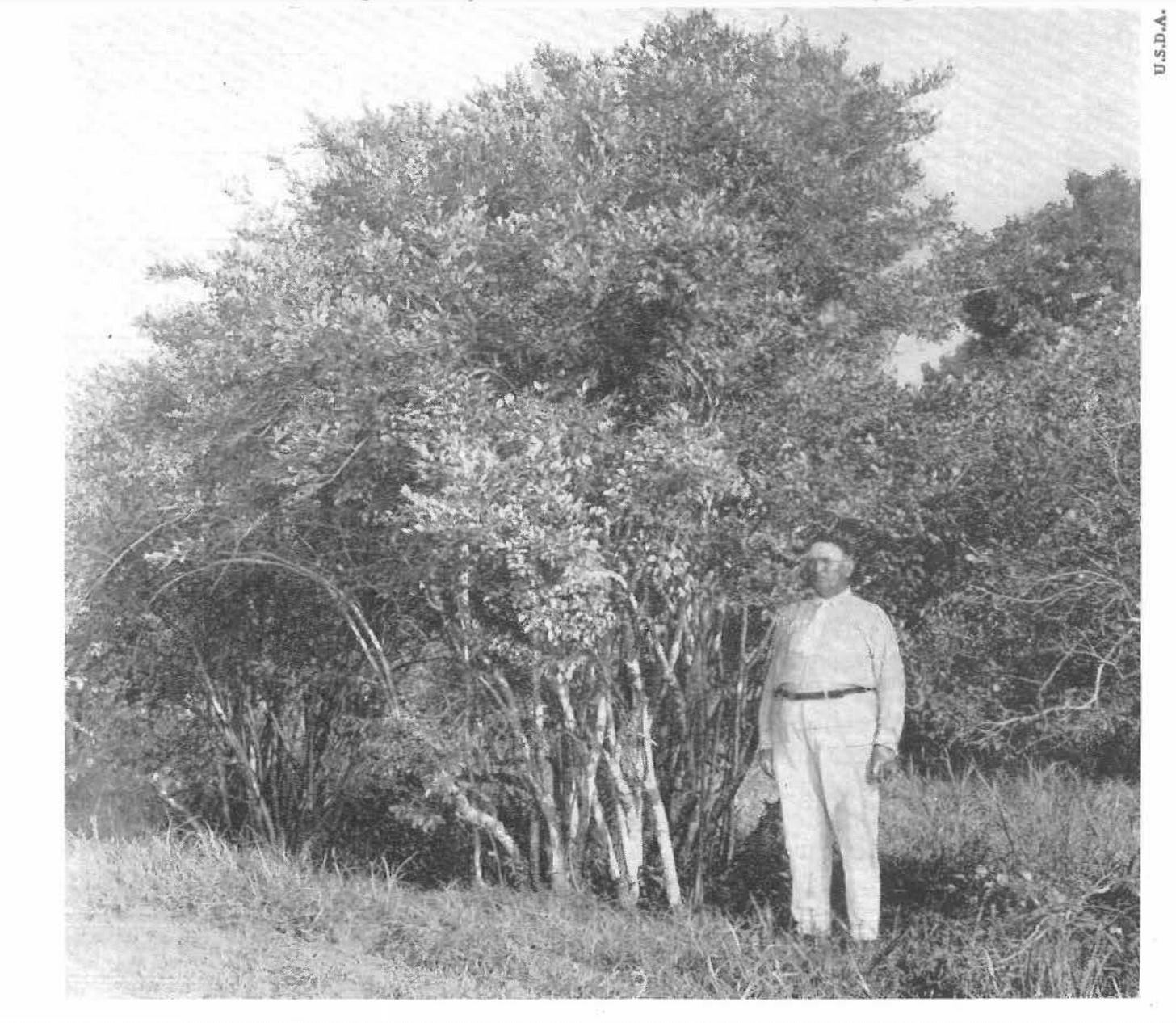

However, while the Great Burn of 1910 had symbolically lit a fire under the wild blueberry industry on the Pacific coast, at the same time the USDA quietly published Bulletin No. 193, titled Experiments in Blueberry Culture, written by Dr. Frederick Vernon Coville. Dr. Coville, had bought a home in New Hampshire as a summer getaway for his kids to experience rural farm life, and it was here he first made two selections among the wild blueberries in 1908-1909, and crossed them in 1911. He realized that blueberries needed acidic soil, cross-pollination, and chill hours to thrive, and provided the first selections from where most of our northern highbush varieties come from today. The fact they produced food on otherwise worthless land meant an unimaginably untapped market. In his words, “These lands are generally valued at a low price, and the chief expense involved in their utilization for ordinary agricultural crops is the costs of correcting their acidity… May we not more effectively utilize such lands by growing on them crops which, like the blueberry, thrive in acid soils?” 16

His status as the father of the modern blueberry isn’t overstated. Over roughly 25 years, when he retired, about sixty-eight thousand seedlings from his selections had fruited and about two thousand acres of named varieties resulting from his work had been planted. The methods of blueberry propagation used today are still the same as he perfected, one hundred years later.17 While Sapp may have created the first blueberry industry and orchard, his blueberries were dug up selections from the Florida swamps.

After Dr. Coville’s initial collection, a reader, Elizabeth White, invited him to her family’s farm in New Jersey, where she and her father operated one of the largest cranberry farms in the country. They were interested in expanding their industry into blueberries, a fruit that had always captured her interest, and offered Covile land to cultivate the plants. She bribed her neighbors with immortality— should they find the best blueberries in New Jersey, she would cultivate and name the selection after them. By 1916, Dr. Coville and Ms. White had transplanted one hundred wild selections, only a few of which they kept. Of these, the modern variety ‘Rubel’ is a selection from her efforts, and that same year they released the first commercial crop of blueberries.

In 1919, White posted an advertisement “offering $50 apiece for wild blueberry bushes bearing berries as large as a cent” in the July issue of Science.18 While we don’t know how many plants she received, within a few short years, Coville developed a marked program. By the early 1920s, White had narrowed her varieties down to six. News articles triumphantly reported about the “taming of the wild blueberry” on her ten acres. The government backed the new industry and spent extensive resources advocating for the new wonder crop, similar to what was also happening to the pecan around the same time. This included state experimental stations in 1916 and sponsorship for research.19 Much like the role of huckleberries filling a gap for canneries, the blueberry industry in New Jersey conveniently filled a gap between strawberry and berry seasons in New Jersey. In 1927, White helped organize the New Jersey Blueberry Cooperative Association, while Dr. Coville continued to crossbreed bigger selections.

By the 1940s, with the explosion in supermarkets and the post-war boom, the blueberry quickly stretched across the country, scaffolded by the Blueberry Hill Cookbook, published in 1959, which made blueberries the fruit to have in your fridge. As selections continued to improve the size and seediness of the fruit, the wild blueberry fell further and further out of fashion. In an attempt to rebrand, wild blueberry producers argued that domesticated blueberries weren’t even really blueberries at all but something of a frankenfruit, similar to the arguments we see about GMOs today. In one Maine resident’s words, “there is no likeness between the two”.20 The domesticated blueberry’s fruit was of poorer flavor, so they said, and that they’d prefer no blueberries at all over the new domesticated crop. In more recent memory, the increased antioxidants of wild blueberries have focused the value of wild fruit on their increased health and ecological benefits.

However, during the mid-20th century, the USDA saw the potential of the domesticated blueberry and invested heavily in breeding and marketing research to turn the blueberry from a forager’s food to a staple fruit on grocery store shelves. Part of the success of this domestication is related to how diverse the genome for vaccinium is; for example, southern highbush cultivars, which require fewer chill hours to produce fruit, have enabled the expansion of blueberries into warm environments, while in the north, native lowbush blueberries are harvested in setting that more aligns with historical blueberry management than our conventional agriculture system. After decades of marketing to make the blueberry a common sight on grocery store shelves, the idea that its place in the American diet is only recent, within the last century, seems surprising. It also points to the capacity to bring new fruits to market, with the right supporting infrastructure.

Today, evidence suggests that much like the pawpaw, the range of the blueberry may grow extensively, retaining its role as an important food source for humans and nonhumans. While we’ve highlighted its role in feeding humans, it’s also one of the most prolific feeders for pollinators in North America and one of the few crops that are better pollinated by native pollinators than honeybees.21,22 Researchers are also working to improve blueberries by creating more productive cultivars using polyploidization and in vitro tissue culture, including the development of 10 octoploid cultivars, named ‘Biloxi’, ‘Legacy’, and ‘Duke’, offering a revitalization of blueberry breeding.23

The biggest challenge for the blueberry industry and blueberry production moving forward will be increased pressure from pests as climate change fundamentally alters the natural control mechanisms for many predators of the plant. However, with a better understanding of the blueberry’s past and ecological framework, there’s a bright future to be had for the blueberry, despite impending climate change.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 14-page chapter, of (so far) a 1281-page book with 942 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #236 of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Connolly, T.J. 1999. Newberry Crater: A ten-thousand-year record of human occupation

and environmental change in the basin-plateau borderlands. Univ. of Utah Anthropological Papers, No. 121. Salt Lake City, UT.

Cummins, L.S. 1999. Pollen and phytolith analysis, p. 202–210. In: Connolly, T.J. (ed.). Newberry crater: A ten-thousand-year record of human occupation and environmental change in the basin-plateau borderlands. Univ. of Utah Anthropological Papers, No. 121. Salt Lake City, UT

Strass, K. 2010. Huckleberry harvesting of the Salish and Kootenai of the Flathead Reserva-

tion. UNDERC West: Practicum in field biology. University of Notre Dame, Dept. of Biology, Land O’Lakes, WI.

Derig, B.B.; Fuller, M.C. 2001. Wild berries of the West. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press. 235 p.

Dean, B.P. (ed.). 2000. Wild fruits: Thoreau’s rediscovered lost manuscript. Norton, New York, NY

Hummer, K. E. (2013). Manna in winter: Indigenous Americans, huckleberries, and blueberries. HortScience, 48(4), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.21273/hortsci.48.4.413

Richards, R. T., & Alexander, S. J. (2006). A Social History of Wild Huckleberry Harvesting in the Pacific Northwest. https://doi.org/10.2737/pnw-gtr-657

Wang, J. (2024). How fruit moves: Crop systems, culture, and the making of the commercial blueberry, 1870–1930. PLANTS, PEOPLE, PLANET. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10557

Freeman v. Underwood. (1877). 66 Me. 229. Available at cite.case. law/me/66/229/.

Utter, M.R. 1993. Rosts on the river. In: Swan River echoes of the past: 1893- 1993. Bigfork, MT: Swan River Homemakers Club: 31-41.

Richards, R.T. and S.J. Alexander. 2006. A social history of wild huckleberry harvesting in the

Pacific Northwest. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-657. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland, OR

Fisher, A.H. 1997. The 1932 handshake agreement: Yakama Indian treaty rights and Forest Service policy in the Pacific Northwest.” Western Historical Quarterly. 28 (Summer): 187-217.

Abbott, A.H. 1933. Huckleberry pie and closed roads. March 21. In: Northern Region News. A newsletter. Missoula, MT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Region. 5(6): 3-4.

Vanek, M.L. 1991a. Behind these mountains: Volume II. God’s country in the United States of America: Noxon, Heron, Trout Creek, Bull River, Smeads. Colville, WA: Statesman-Examiner, Inc. 145 p.

Lyrene, P. M., & Sherman, W. B. (1979). The rabbiteye blueberry industry in Florida-1887 to 1930-with notes on the current status of abandoned plantations. Economic Botany, 33(2), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02858296

Coville, F. V. (1911). Experiments in blueberry culture. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Plant Industry, bulletin no. 193. Government Printing Office

https://daily.jstor.org/delicious-origins-of-domesticated-blueberry/?cid=eml_j_jstordaily_dailylist_06302016

“Scientific Notes and News.” Science, vol. 50, no. 1279, 1919, pp. 16–18. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1643757. Accessed 20 Aug. 2024.

Woodward, C. R., & Waller, I. N. (1932). New Jersey's agricultural experiment stations 1880–1930. New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station.

A Reformed Blueberry. (1916) Oxford Democrat, 18 Apr. 1916, p. 2.

https://www.xerces.org/blog/helping-bees-by-growing-better-food-system

Kayser, Ashley. (2020). What’s Going to Happen to My Pancakes? The Impacts of Climate Change Upon Blueberries and Sugar Maple.

Jarpa-Tauler, Gabriela & Martínez Barradas, Vera & Romero-Romero, Jesús & Arce-johnson, Patricio. (2024). Autopolyploidization and in vitro regeneration of three highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) cultivars from leaves and microstems. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC). 158. 10.1007/s11240-024-02810-9.