Canning has become a cornerstone of the homesteader/prepper community, particularly as a tool of resilience and self-sufficiency. This makes sense, in many ways, as it localizes the production of shelf-stable foods within the home; the only outside requirements are one-time purchases of jars and a rotating collection of lids, which are cheap and produced en masse.

The concept of preserving food through heat, pressure, pH, and fermentation is a long-lived art throughout human history. Canning itself emerged in the early 19th century, driven by the need for reliable preservation, specifically for military provisions.1 However, it did not become a staple part of ‘homesteading’ as we think of it today until the late 19th century. Canning was driven largely by industry looking to stretch food sales far beyond harvesting season. Many early canning industries developed alongside agricultural lands, capturing excess produce that otherwise went to waste or was sold for little profit due to the glut of harvest season (which drove the development of industries such as blueberries). Interestingly enough, this also led to union organizing overlaps with the agricultural sector in places like California, where large immigrant populations pushed for better wages and conditions on the canning lines.

The first community canning centers were often the result of neighborhood organizing to save money, time, and labor. Others were funded by organizations, from county commissioners to school boards, mill owners, and even the American Red Cross.2 These were often a direct response and accelerated due to the widespread decrease in farm incomes through the early 20th century and the increasing affordability of tin cans and glass jars. The biggest challenge was the infrastructure, which was only needed for a short period of time per year. Collectively, however, the canners themselves were affordable, which drove community funding for the equipment. By the late 1880s, there were over 3,800 community canneries in the country, largely to help members of the community preserve surplus produce from their gardens and farms.

These were functionally community centers as well; for example, in 1915, the Texas Agricultural Extension Service (TAEX) introduced community canning centers, which were funded both by public and personal networks. White women organized fundraising and activities, while white men were responsible for constructing, fueling, and operating the centers. These centers allowed small farmers to preserve for themselves and for sale, increasing their income in economically repressed areas while also supporting poor white families that relied on subsistence farming.

In 1915, only one community cannery existed for African Americans. By 1918, that number had increased to 250, as canning was a tool for resiliency through the First World War. For African American families, preserving food was particularly valuable, as most of the farming around them was for cotton, a cash crop, and food prices for African Americans were inflated despite their lower incomes, similar to how food deserts drive up prices today in African American communities. With the development of these community canning centers, “Nearly every African American farm family planted a home garden and preserved the majority of the harvest,” whereas only a few years before, according to county agent Robert Hines, “practically no vegetables were saved and a very little fruit.”

Canning also allowed farmers to choose not to sell produce when a glut had pushed prices down. Crops that would have been a loss were instead made profitable. Farmers, both black and white, were able to take advantage of good markets and timing in ways they’d never been able to before, and consumers had a steadier food supply on their shelves.

Further, the canning centers became important not just as places for education, demonstration, and preservation but also because they forced members to build stronger relationships with people in their community, working as a social center as well as a source of food resilience.3 In Jacksonville, the USDA describes the centers as “really small community centers, where church socials, parties, and community recreational activities are centered. They are equipped to function as emergency feeding centers, and as Red Cross canteen centers.”

As the droughts that would ultimately manifest into the Dust Bowl continued on, state and private partnerships accelerated investments into community canning. The materials put together, such as the bulletins out of TAEX, went beyond canning basics and provided full plans for constructing facilities. These plans were designed to be accessible to semi-literate African Americans while also only requiring materials that would be within reach of poor folks in rural communities. Agents also worked to meet people where they were, for example, doing canning demonstrations on a creek bank “because water was available at the creek but not at the home.”4 Plans were designed to discuss drainage, sanitation, and even which native shrubs to use for landscaping, which could also provide useful materials, such as berries. Many residents not only received the benefits of these canning centers but went on to apply the knowledge in other communal spaces, such as churches and schools.

During the Jim Crow era, offering another tool for autonomy was another form of resistance for black Texans. Communities were able to self-govern their centers and fund their own investments, regardless of the white power structure. Families grew their own food, canned their own food, and profited from their community’s own means of production.

In 1929, black families canned more than one million jars of food, an average of 115 cans or jars per family, at an estimated value of $371,518.70, or $6.85 million in 2024. Residents paid for access to the cannery with a percentage of their produce, which was sold and paid for the cannery's operating costs. In this way, canneries were self-sustaining after the initial investment and continued to be both a source of individual and community pride. Producing food for oneself was not only self-reliance but also giving back to the community, improving the entire community.

As the depression worsened into the 1930s, momentum continued. Four more African American canning centers opened in 1931, followed by twelve in 1932 and forty-three more in 1933. One of the canning centers built in Beulah County in 1932 is worth noting—residents salvaged materials from an old hall destroyed by a storm and pooled two years’ worth of winnings from a local county fruit display. The TAEX resources and New Deal efforts to fund rural relief (which we talked about here) helped fill the gap for many of these centers. All but three of the canning centers across Texas were owned by communities and cooperatives.5

Canning centers exemplified the goals of Russell Lord and Liberty Hyde Bailey; they strengthened rural communities by generating a common interest in community resilience, identity, and life and became a forum for African Americans to build racial solidarity. Unlike the competing churches of poor communities, which could turn to strife in order to raise funds, canneries required residents to cooperate collectively to purchase bulk seed and negotiate planting schedules and harvesting times in order to make sure the cannery would be available for all of the produce to be processed efficiently. Mary Evelyn Hunter argued that the centers did more “to increase community interest than any one thing undertaken.” The centers were more than simply a place to process food; they were the sites for most major gatherings, strengthening community identity.6

As the government looked to save rural communities, canning centers were established as community works projects under FDR and used to process products from cultivated acres of land that were also relief projects. These products could then be distributed to those in need. Centers were overwhelmingly in the southeastern United States, and a clear difference in funding existed between canning centers for black and white communities.

Despite the extensive existence of these canning centers, little research outside of what we have cited above has explored the role of community canning centers in African American communities or in terms of women’s empowerment, given that in many canneries, women made up the entire staff. At the time, canning and food processing and ultimately “women’s work”, yet it also gave women an opportunity to subvert domestic narratives by claiming power and leadership within the community.

Further, while centers were often segregated, in many communities, white-only canning centers were accessible to non-whites during specific time slots.7 For comparison, white patrons in Farmville were offered twenty hours a week, while African-American users were only offered four and a half hours per week.8 Despite this damning accessibility challenge, African-American communities were more equipped to tackle the food shortages and struggles of the Great Depression, despite suffering worse from the economic collapse.

or many impoverished African Americans, the transition from World War I communalism to 1920s individualism during the Roaring Twenties, and then back to communalism during the Great Depression, was never felt, as a legacy of marginalization had cultivated a distinct collective consciousness within black America. For African Americans, the need for social support networks, or communalism, never dissipated.

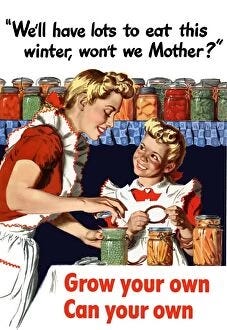

World War 2, however, helped bring more resources to black and white communities through community canning centers and the war efforts to advocate for victory gardens. The government used every tool to draw (primarily) middle-class white folks into food resilience.9 For example, the 1946 USDA Community Canning Centers pamphlet opens more like an eco-anarchist’s manifesto as opposed to a government guide for building a small processing facility:

Community canning centers will not just happen. They must be planned and arranged for well in advance of the season in -which they are needed. Planning soundly and getting the center operating on a business basis from the beginning are necessary if the center is to be successful over a period that justifies the expenditure of money and effort involved.

Successful canning centers usually are the result of group action spurred on by some individual who sees the need for providing facilities for preserving food and has the energy to do something about it. It doesn't matter who this is — an energetic homemaker, a home demonstration agent, a businessman growing his first garden, a teacher of vocational agriculture or home economics, or a civic leader.

During World War II, government propaganda campaigns actively promoted home canning as a patriotic duty for women, framing it as their contribution to the war effort. Community canneries, often led by home demonstration agents, reinforced these gendered expectations by providing women with the training and resources to fulfill their perceived domestic obligations. However, this framing of canning as women's work also provided women with opportunities to exercise agency and gain recognition for their contributions to the community.

These spaces offered women a platform to exert influence, build community solidarity, and challenge existing power structures related to food production, distribution, and consumption. A central concern for women in community canneries was access to essential foodstuffs, especially during wartime rationing. Sugar rationing, for example, became a hot-button topic; women needed sugar for canning, which was readily available for businesses that sold sweets but unavailable for canning centers. Women went to the press, advocating, organizing, and protesting for access to sugar.10

However, despite the discussions of the massive increase in canning centers, only 1% of white women who canned in 1943 did so in a community canning center. Many women, particularly in urban and suburban communities, felt they had no time, equipment, or food to can; that canning in white communities was predominantly for upper-middle-class white women and poor rural white women. This trope feels eerily similar to the modern homesteader movement, which is driven by need or by influencers.

African American women, comparatively, were overwhelmingly drawn to communal canning centers despite the risks of claiming space as black women in the pre-Civil Rights era. One booklet described African American women in Detroit who “courageously” attended a canning demonstration during a race riot and were unable to return home for three days.11 The need for canning in poor African American communities, even in the North, was magnified exponentially compared to much of middle-class America.

This was obvious when it came to growing food as well. African Americans carried a disproportionate weight of Victory Gardens— as the labor force maintaining them and also the owners of more gardens. For example, in Dallas, 90% of African American families had gardens, in comparison to 40% of their white neighbors. It’s no surprise, then, that canning was much more central to African American communities than to white ones.

For context, in 1943, more than 4.1 billion jars of food were produced in homes and community canning centers, making up 40% of the vegetables consumed in the nation—or at least as was reported. Private correspondence suggests otherwise—for example, a study in Maine noted that although 93% of families in Waldo County had gardens, 18% of them were considered “poor,” and another 39% were considered only “fair.” In reality, the Victory Gardens were to keep the poor from starving while allowing middle-class Americans to feel as though they were contributing to the greater cause when, in reality, poor, marginalized people bore the brunt of the war shortages.

While the immediate post-war period witnessed a decline in community canneries, the sources demonstrate their enduring value and adaptability. They persisted in various forms, reflecting the evolving needs and priorities of communities while continuing to provide essential services and fostering connections around food, knowledge, and shared resources. Community canneries, particularly those that survived into the later 20th and early 21st centuries, adapted to changing community needs, expanding their functions to include food safety training, nutrition education, and support for local food systems. Some canneries even became entrepreneurial ventures, providing canning services for local farmers and food businesses, illustrating their continued relevance in specific contexts.

Community canneries, particularly those that survived into the later 20th and early 21st centuries, adapted to changing community needs, expanding their functions to include food safety training, nutrition education, and support for local food systems. Some canneries even became entrepreneurial ventures, providing canning services for local farmers and food businesses, illustrating their continued relevance in specific contexts. Many are multi-use spaces, test kitchens for would-be food producers developing niche products, and many integrate business education into host resources. Some, such as one center in Minnesota, pair their cannery with community gardens.

In an increasingly disparate world, community canning centers offer us a new way to rethink our relations with our neighbors. Similar to libraries, these centers can provide economic benefits while forcing us to find common ground with the people around us in new, exciting ways.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 10-page chapter of (so far) a 1348-page book with 1049 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #244 of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and, in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

https://gardenhomehistory.com/2010/11/19/the-garden-home-co-op-cannery-early-1940s-1950/

United States. Bureau of Human Nutrition and Home Economics. Community Canning Centers. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1935.

Federal Extension Service, USDA “Community Canning Centers” Sept 14, 1944.

Reid, Debra Ann. "Locations of Black Identity: Community Canning Centers in Texas, 1915-1935." Research and Review Series, vol. 7, 2000, pp. 37-50.

Robert Calvert and Arnoldo De León. The History of Texas (Arlington Heights, Ill.:HarlanDavidson, Inc.,1990),300.

Hunter, “History of Extension Work Among Negroes in Texas,” box 4, TAEX Historical Files. Annual Report, 1925, 68. Hunter, “Outstanding Achievements in Negro Home Demonstration Work,” box 4, TAEX Historical Files.

“Farmville Canning Center Opens To Save Surplus Food.” The Farmville Herald, June 18, 1943.

Evans, Hannah Janine. “Grow All You Can, and Save All You Grow”: Innovation and Tradition at the Prince Edward County Community Cannery. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2020.

Bentley, Amy 1998 Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics of Domesticity. University of Illinois Press, Champaign.

“Sugar for Canning and Preserving",” on National Farm and Home Hour, April 30, 1942.

Roberta Hershey, “Practical Home Canning,” in Gardening for Victory: A Digest of Proceedings of the National Victory Garden Conference, holding in Chicago, Novemebr 16-17, 1943.

This is completely awesome!

I'm in the Sacramento area and happened to be arranging a skill share of this type--drying, in the first instance--coming up early next month. I'm hoping that works out, and have pressure canner I'd like to see used a LOT more of the time than it currently is.