Homesteading & White Supremacy

How 200 years coalesced into the current right-wing white supremacy prepper movement

We’ve covered the permanent agriculture movement at length at this point, and you can read its development here and here, we discussed the concerns folks like Russell Lord, Liberty Hyde Bailey, and even the Odum brothers had with the Jeffersonian vision of individual homestead subsistence as a concept to address the increasing alienation of urbanization and precarity of industrial agriculture that was made present by the Dust Bowl, among other things. Further, we covered recently the divisions in the permanent agriculture movement post World War between the Odums, biodynamic, organics, and even the permaculture movement, as well as agroecology’s marginalization here in the United States because of the Odums.

To fully understand the homesteading movement as it’s understood in the United States, we need to back up the Morrill Act— the same act responsible for the expansion of agricultural education, and how that played into an opportunity for land access for (primarily) white folks and the systematic, racist attempts to remove Indigenous people from their rightful lands. We have to discuss how this overlapped with white supremacy from a historical context, how that reared its head during the permanent agricultural movement with the rise of the Southern Agrarians, and then again how purity ethics once again emerged in the 60s, 70s, and 80s as countercultural movements divided with the birth of Reaganomics and the anti-science crowd that attempted to cling to the Odums for legitimacy. This is particularly poignant as white supremacy and homesteader culture as a new aesthetics from influencer homesteader accounts to the cottage-core movement.

Without this wide scope of understanding how alternative agricultural movements have existed over the past two centuries, it’s difficult to see how white supremacy has tied into these movements, and why the idea of “growing your food” comes with some difficult baggage that we’re going to try and unpack here. We’re going to try and engage with this content from World War 2 and on since we have covered many of the overlaps between self-sufficiency, self-determination, and white supremacy.

The Vietnam War gave birth to a new generation of veterans, ones who came back from war feeling abandoned by their government and by their fellow civilians. Unlike prior wars, the enemies were largely non-white and the terrain of war was entirely different. Guerrilla war and traps created the conditions of dehumanization that bled racism into anti-communism. Upon returning home, many found themselves disgusted by the United States government and found the country they returned to much different than the country they had left, as progressive policies had taken hold through the late years of the 60s and early 70s. We highlighted this with the rise of the Back to the Land movement, and how the countercultural revolution fed into new visions of the future.

Many point to the startling rise in white supremacy in the late 20th century to the aftermath of the Vietnam War. As narrated by white power proponents, the Vietnam War was a story of constant danger, gore, and horror. It was also a story of soldiers’ betrayal by military and political leaders and of the trivialization of their sacrifice. This narrative increased paramilitarism and separationism through homesteading and communes within the movement. In his speeches, newsletters, and influential 1983 collection Essays of a Klansman, movement leader Louis Beam urged activists to continue fighting the Vietnam War on American soil. When he told readers to “bring it on home,” he meant a literal extension of military-style combat into civilian space. He referred to two wars: the one he had fought in Vietnam and the white revolution he hoped to wage in the United States.

But before we can dive into the Vietnam War, one more key component of this period needs to be recognized. The year 1969 was the birth of the Citizens Law Enforcement & Research Committee, founded by Identity Christian Henry L. Beach. While we had mentioned that the Back to the Land movement found cheap farms, these were at the cost of family farms that had been hit with foreclosures, which accelerated through the 1970s.1 The Posse Comitatus, a freeform group that spun off of the Citizens Law Enforcement & Research Committee, absorbed many of the angry farmers who found themselves losing their homes as high interest rates, paired with the drop in demand for crops as well as higher property taxes crushed small farmers. This precarity further caused farms to drop in price, sometimes by up to half of their values in a few short years, leaving no equity for farmers to all upon in hard times. Within the century, for context, nearly half of the nation’s 2.2 million farmers would lose their farms.2

The name Posse Comitatus refers to the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 which forbids the use of US military & national guard forces as civilian forces. Because of the context, stopping the government from overseeing southern elections, it has been interpreted to imply various attempts at unilateral authority.3 The Possee Comitatus has taken this to mean that any oversight by federal government can be considered an overreach of authority; that income tax, social security tax, drivers’ licenses, and more are all violations of the constitution. However, the Posse Comitatus claimed for themselves a holy right to the land, much as Identity Christians and much like we saw with the biodynamic leaders decades prior. This holy right, in most senses, is simply a reframing of the manifest destiny responsible for the reshaping of the landscape that is now considered the United States.

As the years raged on, and farms fell one after another, many farmers— who were also often veterans of the Vietnam War— found themselves drawn to conspiracy theories, and given the role of banking in their plight, white supremacy found a new reason to work its way into the subconscious of many. While the Great Society had improved lives in many ways, alongside the Civil Rights Act, declining standards of living across the nation, particularly for middle-class white men, began to create new pressures on the system. The new global economy that was supposed to keep the world from spiraling into World War 3 was viewed instead as an insidious plot to erode the power of white men, as jobs were outsourced, wage growth slowed, and more labor competition made it more difficult than ever to find a job. Paired with a massive influx of young men returning home from war, looking for jobs that no longer existed, in a nation that didn’t seem to care about their sacrifices, which combined created the tinder for a fire that would tear apart the nation for decades.

Now, for some context, it is not uncommon here in the United States for a population bump in Klan membership. Veterans not only joined the Klan but also played instrumental roles in leadership, specifically around providing military training to other Klansmen and oftentimes carrying out acts of violence.4 Veterans offered expertise, training, and culture to paramilitary groups. Although this bump in membership was common, the conditions of the Vietnam War made these veterans different than those who had returned home in the past.

To understand why, we have to understand how Vietnam was different. Unlike prior wars, the Vietnam War wasn’t about claiming territory. Enemy lines and allies were indistinguishable.5 And because success was often measured in the number of people killed, rather than in the terrain held, the war created a situation in which violence against civilians, mutilation of bodies, souvenir collecting, and more were features of war that were fundamental to the act of war itself.6

Returning home not as heroes but as enemies created a specific narrative for the veterans. The corrupt government sent soldiers to Vietnam and then denied them permission to win by limiting their use of force against what they considered to be a beastly, subhuman enemy. Many met gruesome injury and death, and all faced hardship, insects, abandonment, rot, and disease. Those who returned were denied the parades of previous generations and their proper place in public memory. This series of betrayals, the narrative concludes, shows the corruption of the American government but protects the honor of the soldiers. Like many movements on the far-right today, the nation and the arms that enforce the laws are noble, while the enactors of the laws are the crux of the problem.

These soldiers who joined the Posse group continued to radicalize and militarize the movement, bridging it to white supremacist movements. For example, in 1974, a Wisconsin group of Possee members abducted an IRS agent they lured to a farm and assaulted him. In 1975, another Possee group in California brought in 40 armed men in an attempt to stop United Farm Workers organizers from entering tomato fields once belonging to a farmer whose farm had been foreclosed. In 1976, in Oregon, seven armed Posse members tried to take over a 6,000-acre farm to settle a land dispute.7 Militarization was a core function of the organization’s focus on its holy claims to the land.

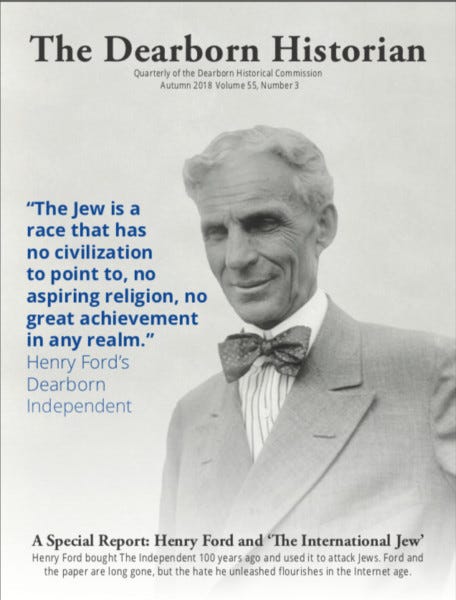

Now, this pairing of farmers and anti-semitism wasn’t a new phenomenon. Henry Ford personally funded a weekly newspaper in the 1920s called the Dearborn Independent that focused on the “Jewish international conspiracy” that was behind the development of communism, eventually anthologizing the content into a book titled The International Jew. It sold half a million copies in a nation where farms were going bankrupt daily, while the Independent would write a series titled “Jewish Exploitation fo Farmer Organizations.” and many other similar columns, acutely aware of the precarious position most farmers were in.8 Ford attacked both sides of what he considered the “Jewish Problem”, trying to highlight the secret cabal of the rich and also funding investigations into suspected communists. The Christian Identity movement that Henry L Beach belonged to before forming the Posse Comitatus proliferated because of Ford’s work (at least in the United States).

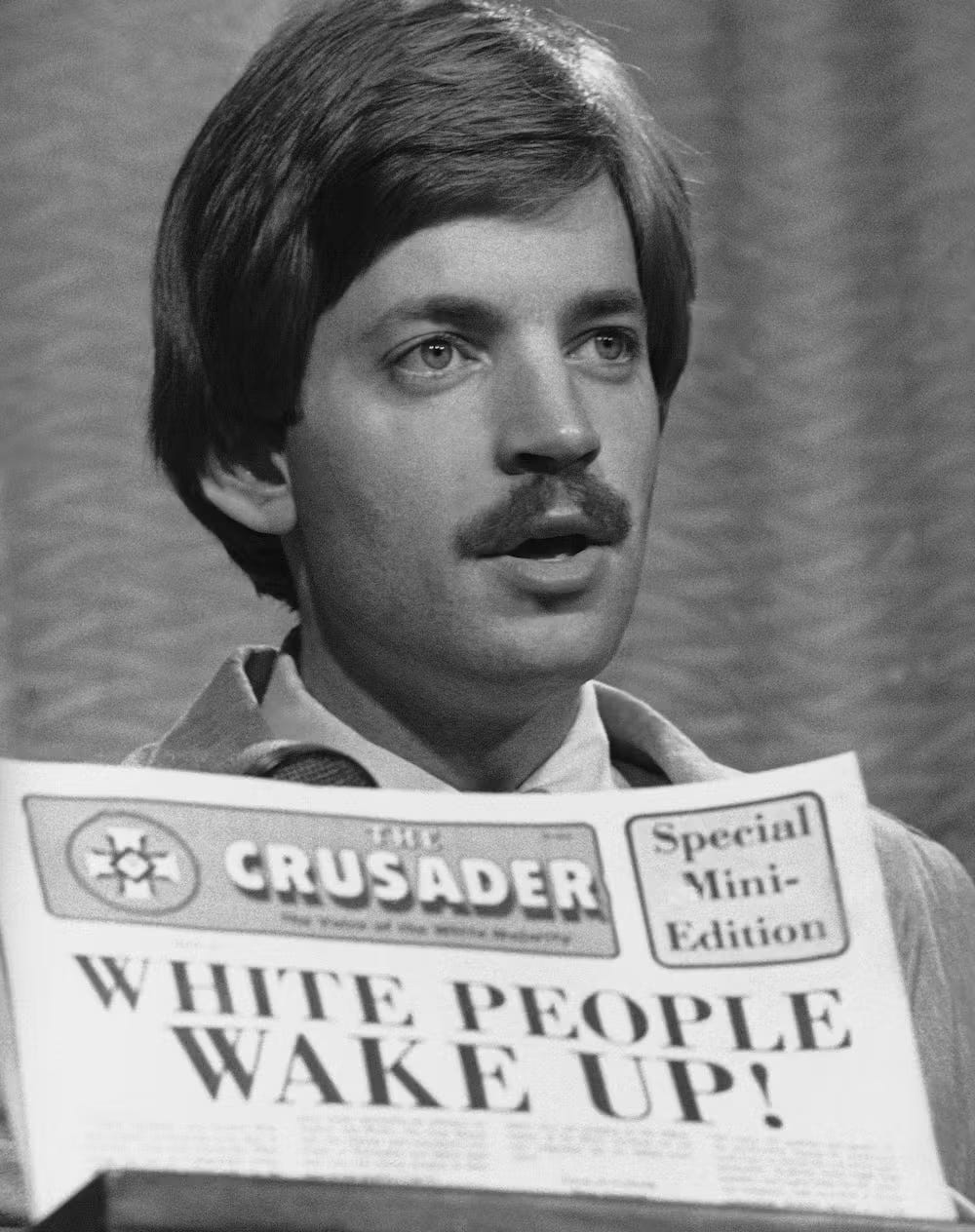

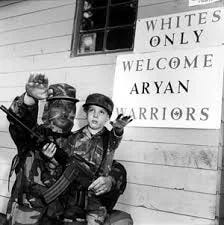

At this same time, David Duke and the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKKK) were rising as a new image of white supremacy was taking shape in the public space. This new public image of the Klan was better-educated and genteel. He gave witty talk-show interviews wearing a suit and tie, claiming to be not racist but “racialist,” and advocating separatism rather than violence. Duke explained that people of color weren’t the enemy but merely childlike dupes of Jewish people and, especially, communists. The plan for racialism was two-pronged, with the “legal” side operating as PR, while more extreme radicals like veteran & writer Louis Beam worked to build the infrastructure of the movement— specifically, training grounds for para militarism & homesteading communes where white people could actualize their fantasy of white only communities These communities began as individual homesteads and eventually communes, which were scattered across the nation, although the Pacific Northwest was a hotspot for these types of communities due to the Aryan Nations attempting to develop a congregation fo 144,000 homesteaders.9

Three veterans in particular were responsible for the ability of the movement to thrive. Louis Beam, who had served in Vietnam, and Richard Butler and Robert Miles, who claimed to have fought in World War II, Miles with the French Foreign Legion.

In 1977, Louis Beam used a Texas Veterans Land Board grant—a program designed to provide economic benefits to returning veterans—to purchase fifty acres of remote land.10 The swampy landscape was a stark reminder of the rice paddies of Vietnam and the Vietnam War-style training facility was designed to turn motivated Klansmen with no training into soldiers.11 Over the next few years, Beam would climb from participation in a small Klan group to leadership of a national, unified white power movement that shared a paramilitary orientation and adopted violent methods.

These training centers, began to spring up around the country, attracting white supremacists, would-be mercenaries, survivalists, and anyone in between. In 1982, in response to repeated boat burnings by KKK members against Vietnamese fishermen, a judge in Texas ruled that the training facilities violated state laws regarding private armies, the State demanded the KKK shut down any training centers and disbanded the “Texas Emergency Reserve”, white supremacist militia that had been active in Galveston, Texas. While they were shut down in Texas, they had continued to spread across the United States.12

To build long-term solidarity within various white supremacy movements, activists relied on techniques of royalty. Intermarriages connected key white power groups, and Christian Identity and Dualist pastors provided marriage counseling. White power activists, who often traveled with their families, stayed at each other’s homes and cared for each other’s children. They participated in weddings and other social rituals and depended on others in the movement for help and money when arrested. They founded schools and homeschooling content to teach their ideas, weddings, and last rights for the dying. These permanent ties held the movements together, regardless of whether communes were shut down, and allowed chains of communication to remain open throughout various extremist activities.

Pairing religious events with their fundamental belief in white supremacy highlights how a large contingent of white power activists in the post-Vietnam moment believed in white supremacy as a component of religious faith. Christian Identity congregations were told that whites were the true lost tribe of Israel and that nonwhites and Jews were descended from Satan or animals. Other racist churches adopted similar theologies that identified whiteness as holy and that to be holy meant to protect the white race.13 And it was easiest to protect future generations of the white race by moving to rural, primarily white communities, which were often found in the Pacific Northwest.

Part of this religious faith was framed in wholesome lifestyles at their compounds—that is, zero popular media, abstinence from drugs and alcohol, subservience of women, race-based education of children, and enforced rules framed within a Christian Identity interpretation of the Bible. This would later change in the 90s but was a key part of the ‘traditional’ lifestyles mandated by the movement’s leaders and strict religious framework. In many ways, the movement was tied to a Puritan ethic the same way that the Back to the Landers was tied to full disconnection from industrialist capitalism, often at the cost of their own comforts.

The movement’s religious extremism was also integral to its broader revolutionary vision.14 It was believed that they would be tasked with ridding the world of the unfaithful, the world’s nonwhite and Jewish population, before the return of Christ.15 At the very least, the faithful would have to outlast the great tribulation, a period of bloodshed and strife. Many movement followers prepared by becoming survivalists: stocking food and learning to administer medical care. Other proponents saw it as their responsibility to grow food, build militias, and train themselves for the upcoming race war.“

Essential in binding the movement together was the 1974 white utopian novel The Turner Diaries, which channeled and responded to the white power narrative of the Vietnam War.16 The novel provided a blueprint for action, tracing the structure of leaderless resistance and modeling, in fiction, the guerrilla tactics of assassination and bombing that activists would embrace for the next two decades. The popularity of The Turner Diaries made it a cornerstone among movement members and sympathizers that brought them together in a common cause. At this same period, the oil crisis in 1973 accelerated fears of imminent chaos— the realization that natural resources would not always be cheap and readily available hit the pockets of working-class people in a way they never had before.

And The Turner Diaries had the answers.

For example, Robert Miles, one of the other chief leaders of the movement, proposed an organized network of white power cells inspired by The Turner Diaries: 600 centers, positioned 100 miles apart and outside of the range of likely Soviet nuclear strikes against the United States. Unsurprisingly, this put cells in rural areas across the nation. Miles was preparing for an apocalyptic battle or post-nuclear moment, a mandatory seizure of guns—or simply to concentrate white power within rural communities where a few cells would have the largest impact. However, ultimately, the vision was for an all-white nation in the Northwest.

Miles claimed his call to migrate was reprinted in “a dozen different publications,” including Calling Our Nation, the Inter-Klan Newsletter and Survival Alert, Instauration, and National Vanguard, and was reprinted as a standalone pamphlet with 15,000 copies.17 Richard Butler, the third primary leader in the movement, also advocated migration.18 White Aryan Resistance (WAR) leader Tom Metzger echoed Miles in romanticizing the Northwest. He wrote that “the spirit of the cowboy and the woman pioneer are everywhere evident as tall, mostly Nordic Aryans ranch and farm while their children ride horseback.… [T]he prices for food and clothing are fully 10 to 40% cheaper than in other areas.” The Northwest would be their homelands, come the apocalypse.

But they weren’t the only ones with a vision of a white homeland. Another commune, led by the Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord—was explicitly preparing for the apocalypse, and highlighted the dreams of many homesteaders today. Surrounded by low, wooded mountains, Bull Shoals Lake, and the Arkansas border, the 224-acre Zarephath-Horeb compound could be accessed by only one road. On the compound, seventy to ninety members lived and married, delivered babies, attended church and school, and worked in factories on the premises. As did the residents of the Aryan Nations compound in Idaho, they attempted in many ways to live simple, highly moralized lives. Their world was framed in self-sufficiency and paramilitary training for the inevitable apocalypse.

White supremacy and the development of compounds, communes, and homesteads continued as the 1980s rolled on while farmers lost their farms at accelerating rates. The Posse Comitatus continued to use the struggle to advocate for their ideology, including with a new broadcast in 1982 over radio station KTTL in Dodge City, Kansas. This gave the movement access to the Midwest, and it allowed them to infiltrate the nascent American Agricultural Movement (the AAM), whose goal was to get President Carter to raise farm prices. As the AAM grew, so did the Posse Comitatus and its beliefs, which spread across the AAM, injecting the movement with conspiracy theories, anti-Semitism, and Christian Identity philosophy.

Concurrently, the Posse focused its energies outside of violent terrorism to also apply “paper terrorism” such as tax resistance and filing nuisance liens and lawsuits, to make the lives of their targets miserable. In 1980, an estimated 17,222 individuals were estimated to be involved with tax protests through the Posse. By 1983, that number jumped to 57,754. Groups like the Virginia Patriots Network conducted special seminars in tax resistance.

In 1983, the Posse found its first martyr in Gordon Khal, a decorated World War 2 veteran who had joined the movement in 1974. He publicly announced his refusal to pay taxes and was arrested two years later. He was later released on probation and immediately continued to refuse to pay taxes. On February 13, 1983, marshals tracked Kahl in Medina, North Dakota, where a shootout began. After killing two marshals, he was on the run for four months, hiding in a survivalist bunk which was found on June 3rd. After a fatal exchange with a local sheriff, a grenade caused the explosion of over 100,000 rounds of ammunition, making Kahl a hero in the movement.19

The anti-Semitic explosion in rural America was so pronounced, that the Anti-Defamation League commissioned a poll to get a better grasp of what was happening in the nation in 1986. Seventy-five percent of respondents blamed “big international bankers” for farm problems, and thirteen percent specifically blamed Jewish people. Twenty-seven percent agreed that “Farmers have always been exploited by international Jewish bankers.”

Other groups, such as the Iowa Farm Unity Coalition & the National Family Farm Coalition directly attacked the Posse’s movement, offering an alternative to the Posse’s conspiracy theories, white supremacy, and anti-Semitism.20 These groups worked to out their darker events, and physically threatened leaders, making it difficult to meet, even in church basements, where the had operated for decades without challenge.

At the 1986 Aryan Nations World Congress in the Northwest, Miles pressed activists to pack up and move. He believed that the Northwest nation for whites would not need to be won by violence but simply by migration and reproduction.21 Revolution, he said, would be made “not with guns, not with violence, but with love for each other. We will flood the Northwest with white babies and white children so there is no question who this land belongs to. We are going to outbreed each other.” Miles added that this strategy should allow “as many husbands and wives as required” for each white woman to bear five to ten white children.”

It’s here we see the role of white women in protecting the purity of the white race. Women’s reproduction became distilled as a specific cause in Order member David Lane’s slogan, penned in prison and widely circulated: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” It was expected that women would make the war possible by bearing those future soldiers, that they would nurse the wounded, that they would be responsible for food storage and food production, and meet the needs of the revolutionaries. While the men trained in weapons and mass destruction, women centered their training around survival in the apocalypse— canning, growing food, making soap, and keeping their lives operating.

Women also absorbed the role of intergroup mediator, working to bridge across activists within the broad white power movement, even bridging cultural divides as the younger urban skinheads of the 1990s joined the movement with very different values. The role of women in the movement is most apparent in the magazine Christian Patriot Woman, published regularly in the late 1980s by June Johnson, a homemaker in rural Wyoming. Christian Patriot Women framed its message with images, language, and topics defined by the movement as feminine and included practical information for survivalist homemaking. In many ways, it filled the role Mother Earth Magazine had for the Back to the Land movement in the early 1970s, offering basic education across homesteading skills, under the guise of a greater apocalypse.

While the focus was on building these skills for women who had only recently moved to rural areas, Johnson wove through the magazine warnings of the upcoming race war. “We must get this knowledge back … or we’ll never be free of ‘the system,’ ” she wrote, quoting The Turner Diaries. Further, she focused on the expected reality of shortages soon— that before communities were fully self-sufficient, it was important to hoard store-bought food and clean water. In her words;“Life could get pretty [bad] in a very short period of time. We need food, clothing, shelter, and … arms!” A central point of this knowledge was also centered around (explicitly) organic farming, traditional midwifery, and a macrobiotic diet.

Johnston framed this call by referencing the “New World Order,” connecting the paramilitary white power movement of the 1980s to the budding militia movement that used the term much as the old guard had used “ZOG” to claim that an international conspiracy had taken control of the government. While the feminine aesthetic and domestic slant of the journal appealed to the conventional feminine role of women as expected in right-wing circles, it was fully aware of and made the upcoming violence a responsibility for women to bear witness to. Ultimately, the magazine performed several services to the movement— it helped bridge the evolving white supremacy movement to the Posse Comitatus with its language choice and offered several tools for women to accept their role in the revolution, while also providing practical skills to provide better resilience to homesteaders across the nation.

Between the economic crisis that had recked rural communities and the explosion of media focused on Apocalypse (including a bestseller series that interpreted global politics according to the Book of Revelations, which sold 18 million copies), it wasn’t hard to see why people found solace in rural communes that were prepared. A survivalist movement was sparked across the United States. Some, such as the Identity Christians who were fierce premillennialists, expected to battle the Anti-Christ during armageddon actively.22 The countryside was the obvious place to be prepared when nuclear bombs were dropped on urban centers.

It was around this time that the threat of the ZOG, that is the Zion Occupational Government, the theory of the secret cabal of Jewish people who ran the world, was fully replaced with the phrase “New World Order” which more broadly tied global finance, internationalist forces, technology, and the food & pharma industries into a coordinated effort to send the world into armageddon against primarily white Christians. The phrase gained legitimacy when President George H.W. Bush used the phrase in a speech to rally the nation on the cusp of the Gulf War, specifically the role of neoliberalism in protecting the globe.

Now, it’s no surprise that these same issues can be highlighted as key points of the early days of the organics movement, and in many ways we can argue that as the Back to the Landers claimed the terms ‘organic’ and ‘biodynamic’, those who would follow its original politics would find themselves wrapped into this brand of white supremacy. The decentering of Jewish people in this broader international conspiracy helped to smooth the issues of pro-Israel support against the largely-Arab Middle East and centered the fight on an invisible hand of the rich and the rising global superstate, hell-bent on crushing white citizens and freedom.23

As the 1990s crept forward, many of the original leaders of the movement had begun to either pass or become ineffective. While the movement’s rapid growth in the 80s slowed, a new generation of leaders came from the paramilitary groups that had been heavily recruited on the cusp of the Gulf War— many of whom claimed publicly not to be racist, despite overwhelming evidence (much like we see today with the Patriot Front & others).24

It was at this time that the Posse also shifted dramatically. The resistance to their movement from the Iowa Farm Unity Coalition & the National Family Farm Coalition dwindled as efforts to halt the Posse’s growth tired. The Posse recentered their focus on firearms since they were on the ballot with the rise of the Clinton third-way Democratic party. Gun control attracted hundreds of people, and it was easy to tie gun control to state overreach, the United Nations, and the greater New World Order conspiracy.

In 1991, this was further codified for the radical right in Pat Robertson’s (yes, that Pat Robertson) book The New World Order. This New York Times bestseller legitimized bizarre conspiracy theories that have fed the modern patriot movement. Critic Michael Lind provided this scathing review in February of 1995:

Not since Father Coughlin or Henry Ford has a prominent white American so boldly and unapologetically blamed the disasters of modern world history on the machinations of international high finance in general and on a few international Jews in particular.25

Defendants of Robertson point to his support of Israel as proof the work wasn’t anti-Semitic. However, Robertson’s fundamentalist Christianity was colored by dispensational premillennialism, which is a specific interpretation of the Bible that specifically states that Jewish people must return to their homelands for Jesus Christ to return to Earth. Many anti-Semitic Christians have supported Israel for this specific cause, and if they didn’t, they would be undermining God’s plan (and we see this today).26 This ideology was so influential, it heavily bolstered Reagan and G W. Bush’s campaigns. Reagan openly spoke about the need for Israel for the prophecy of the armageddon which would bring Christ’s 1000-year reign. In 1971, Reagan warned the California State Senate:

Ezekiel 38 & 39 says that Gog, a northern power, will invade Israel. Gog must be Russia. Most of the prophecies that had to be fulfilled before Armageddon can come have come to pass. Ezekiel said that fire and brimstone will be rained upon the enemies. That must mean that they’ll be destroyed by nuclear weapons.27

The ideology of the coming apocalypse and the role of these compounds and homesteads paired with a vision in which people were prepared to live strict moral lives, and this often materialized around the role of the white women as the epitome of purity that must be protected. The need to protect white women wasn’t just framed out of the narrative of reproduction; white women were at risk of the hyper-sexualization of ethnic groups, a racist trope that places white men as the protectors of white women.

This narrative was a rallying cry that white men leaned upon when necessary, from the murder of survivalist & white supremacist Vicki Weaver at Ruby Ridge in 1992 which validated the need to protect the purity of “white women” to the Waco standoff in 1995. These moments in history gave new life to the movement as new leaders began to rebrand the movement’s values in order to recruit more followers.

Shortly after Ruby Ridge, one of the leaders of the movement, Pete Peters, published a pamphlet titled The Bible: Handbook for Survivalists, Racists, Tax Protestors, Militants and Right-Wing Extremists. The pamphlet was foundational in the white supremacy we see today; paramilitarism and self-determination outside the reach of the New World Order were central; Noah was a survivalist, Christ was a militant who urged people to arm themselves, and racism and antisemitism were secondary to the cause.28 The priority was anticommunism, stopping interracial marriage, and stopping the abortion of white babies.29 This also allowed the movement to be more public in an age when overt racism was less acceptable to the general public, as we see today with Patriot Front and others.

Despite this public rebranding, in back rooms of meetings, leaders argued for a two-pronged war with the state— the first would be to focus on government overthrow, even if it meant collaborating with people of color. The second war would be to remove the people of color once the threat of state power would no longer be able to stop them.30 “Communism now represents a threat to no one in the United States, while federal tyranny represents a threat to everyone,” wrote Beam in 1992. The focus was strictly political, and in the words of Joe Grego, “there must be ‘legals’ and ‘operatives’,” pointing to the need for a public-facing PR for the movement that was acceptable to mainstream folks— in his words, “you don’t plow gardens with machine guns.”31 This concept was framed in The Turner Diaries, which called for a separation of the legal and paramilitary wings of the movement. Direct recruiting was only to be done by the ‘legal’ units.

This was evident in Waco at Mount Carmel, which was a multiracial community focused on collapse. Yet, it still had a history of organizing with the white power movement and had been an active Klan chapter in 1986.32 Unsurprisingly, in the aftermath, fundraising newsletters would center on one of the fourteen-year-old white girls killed in the siege, with one sharing the caption “Why We Fight”, a reminder of the close ties to the purity of white women.33 These inconsistencies make more sense within this greater narrative of how the white supremacy movement operated.

1995’s Oklahoma City bombing on tax day by McVeigh highlighted the willingness of these movements to take out any targets necessary, and in the case of this particular attack, the murder of children in the second-floor daycare. Copycat bombings were planned across the nation afterward and numerous militias were convicted of stockpiling bombs and armed protests and bomb threats littered abortion clinics and gay bars. Eric Rudolph, a woodsman, and survivalist, set off three separate bombs, one at Atlanta’s Centennial Park in 1996 and three more in 1996 & 1997, targeting abortion clinics and a gay bar.34

The far right wasn’t united around these activities, however. Some conspiracy theorists called them false flags, while other right-wing leaders looked to the left for ways to address the struggles of being tied to a movement they felt was too loaded with baggage. White Aryan Resistance (WAR) leader, Tom Metzger, offers insight into how populist rural politics often don’t easily fit into right-wing narratives:

In its members’ contempt for the federal government, profound antiauthoritarianism, mockery of big business and finance, dedication to complete local control of the community, and a desire to establish wilderness compounds, the new rural radicalism of the 1990s sound surprisingly similar to the counterculture rhetoric of the far left in the 1960s. In fact, in northern California, the Pacific Northwest, and the rural Northwest it is not uncommon for gun-toting paramilitary leaders to live next door to latter-day hippies and marijuana growers… The word populist has been ruined by the right wing, by the manipulations of the Populist Part. We don’t accept that. We began to take on a lot of the positions of the left, and we started recruiting people from the left.35,36

This wasn’t the first time the right and left had overlapped in this way— we saw this as fascism was rising in the 1930s and various socialists found their parties unwilling to recognize the role of industrialism as a focal point of wealth redistribution. In more recent memory, we can look at the role of the Manson Family as a precursor to many of the tropes of the right today.

Charles Manson and his cult were responsible for the murder of Steve Parent, Vooytek Frkowski, Abigail Folger, Jay Sebring, and Sharon Tate Polanski in Bel Aire, California in 1969. The Mansons had prophesied that black people across the globe would rise and slay their white oppressors. The Family, as they were called, would retreat into caves in Death Valley, and after the purge, would claim their rightful position of power and regenerate the white rice. At the murder scene, they attempted to draw a bloody paw print on the wall in an attempt to implicate the Black Panthers and instigate the black uprising.

The Mansons were celebrated from both sides for different reasons. White supremacists celebrated Manson for choosing prominent Jewish figures and for their belief in white man reclaiming proper control over the world. Socialists celebrated Manson for murdering the rich “piggies”. What makes the Manson Family particularly poignant is their model of “intentional community”. The idea of bringing groups of people together for a deliberate purpose was the foundation of the Back to the Land movement and is closely related to how the Manson Family itself emerged. Modern intentional communities modeled on Manson follow the apocalyptic, survivalist component while focusing more on waging a global war, not simply instigating one.

The Manson family is particularly important to understand as it highlights how the left and the right can overlap for seemingly different reasons— and it helps us understand the evolution from distrust of the financial industry and the New World Order to distrust of vaccines and FDA-approved foods. While the left has increasingly found itself distrustful of these same issues, the logic behind this movement is different. It further helps us understand how we see the crunchy-to-alt-right pipeline get filled with unwitting followers hoping to do the best thing for themselves and their families.

While these movements went more dormant in the post-9/11 era, the Tea Party explosion during the 2000s represents a key component of this disaffection, that can be traced back to a constant decimation of rural communities brought on by global capitalism.

We see these narratives continue to evolve in the rise of the crunchy right woman influencer and cottagecore aesthetics. How pureness is reflected in our foods, and how this ties into many of the ideas of the organics and biodynamic movements.

While we have looked at this movement as largely separate from the Back to the Land movement, there was significant overlap between right-wing and left-wing rural communities. We had mentioned the Aryan Nations, who founded a compound in Idaho, which, while explicitly a white supremacist movement, appealed to several left-wing homesteaders who were attracted to the beauty of the region and learned to live side-by-side with them. Next to Puritan white supremacists stood tepee-dwelling hippies. We had talked about the evolution of Mother Earth News in the Back to the Land piece, but even before it moved further right-wing, it was often used by white power activists to connect through the classified section. What bound these movements together was a consensual understanding that the system as it was could not continue. The looming apocalypse, driven by the New World Order or late-stage capitalism, meant that the folks on the other side of the proverbial woods were a problem for another day.

It’s estimated that in the 1980s, there were at least 25,000 “hard-core members” of the white supremacy movement. An additional 150,000 people at least purchased white power literature as well, and nearly 500,000 are estimated to have at least read those various magazines. For context, the right-wing John Birch Society only reached 100,000 members at their peak.37,38 At its peak in the 1990s, the militia movement had swelled to around 5 million members & followers, which was, at its time, larger than the peak membership of the Ku Klux Klan, which had peaked in 1924 at four million.39

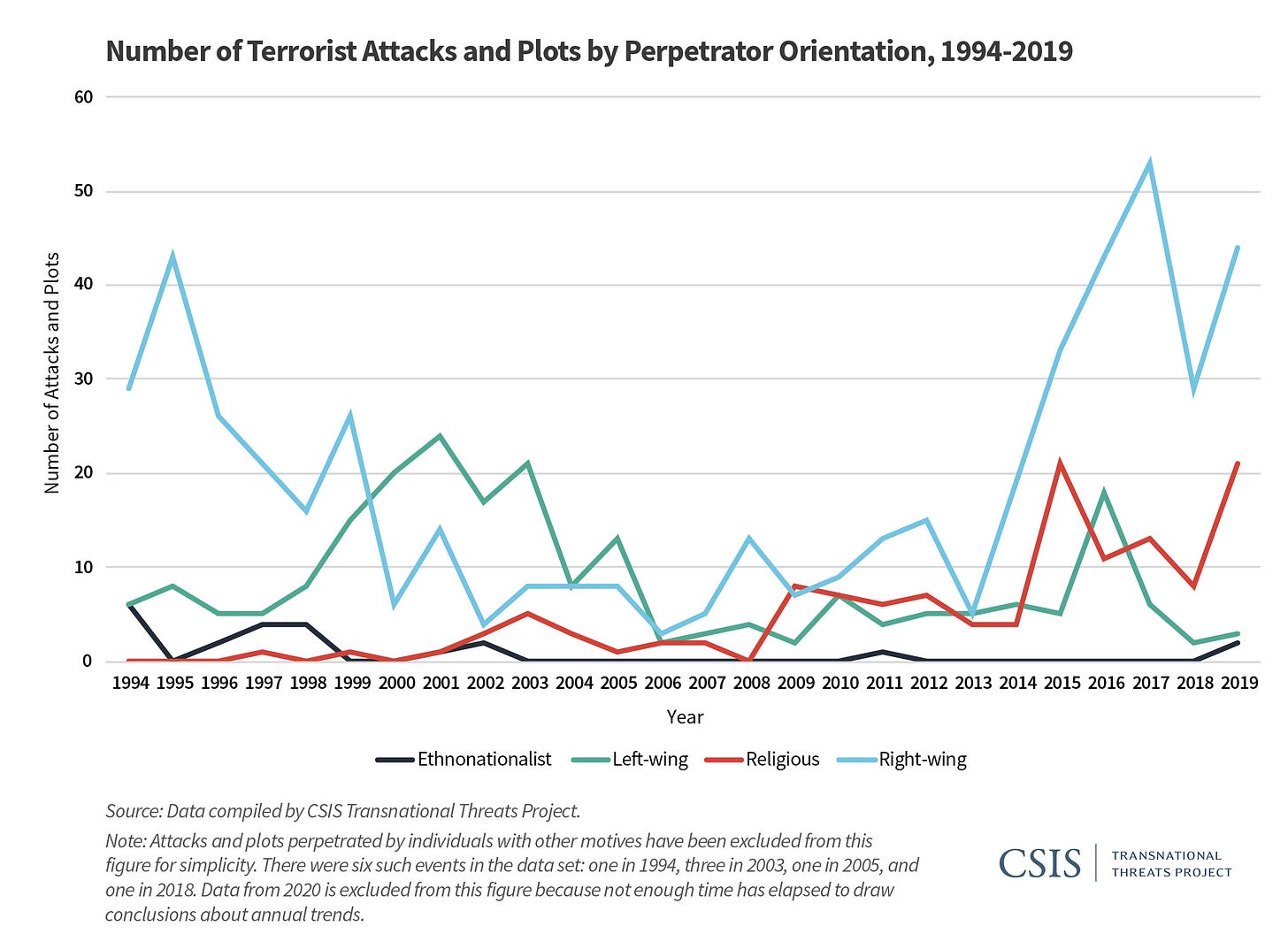

Today, there’s estimated to be 1,096 '“patriot groups” and at least 240 of these are identified as militias. Experts estimate that around 15,000-20,000 members of these militias are military veterans, and despite the drop in news coverage of white supremacist incidences since the Biden election, attacks have actually continued to rise.40,41 While we don’t have any real measure today of how many people today would politically align themselves with militia-type movements and fundamental Christianity, based on the number of plots and attacks by right wing & Christian Extremist groups, it appears that we are at the very least equal to that peak in the 1990s, if not higher.

Contemporary right-wing homesteader culture holds vast space, from conventional homesteading along the lines of Joel Salatin (who only a few years ago delivered a racist tirade to black-indigenous farmer Chris Newman, you can read about it here) to Cottagecore aesthetics to the crunchy anti-science spotted across social media highlighting “proof” of the secret poisons being forced on us daily. This is evident when you look at the proliferation of right-wing homesteader content and the ease in which searching for gardening content leads to racist conspiracy theories.

These racist influencer accounts aren’t just content for the digital space, but often leak into the outside world— only a few years ago the owners of Schooner Creek Farm (known online as “Volkmom”) were found promoting white nationalism and “white American identity”, causing the local farmer’s market to be suspended periodically over public safety concerns.42 Eco-fascism specifically has seen a resurgence over the past decade, a theme that’s worth exploring at some point (although beyond the scope of this piece). While not as forthcoming as you’d expect, Volkmom’s username is a referral to the Völkisch movement, which was a push against capitalism in Germany and a return to rural peasant life.43 This is significant because it highlights the ways that right-wing extremism is often less tied to free market economics as we understand them today and rather the decentering of power from a handful of rich people.

These influencers tie these narratives together, similar to how the movement had done forty years prior; the same voices for eco-fascism and natural food are most often the ones advocating and platforming homeschooling, taking over school boards, disrupting drag shows, and branding it all under individual sovereignty and the need to protect the purity of their children. Much like the fascists of the early 20th century (and before), the movement seeks to center individual sovereignty and a collective good for specific people, often at the expense of others.

Much like the explosion of the Klan in the 1920s, centering content around the vulnerability of individuals within a global economic scheme with little concern for individual health or sovereignty has offered a new way to recruit members for a militant white power movement. June Johnson’s homesteading magazines that proliferated across white supremacy compounds in many ways reflect the social media of homesteading today, which offers new ways to engage with ‘traditional’ lifestyles— from “trad wives” who focus on whole foods and clean living to men showcasing simple ways to live off the land, appealing to the reality that it is harder to be a man today (and not for the reason you think).44

Within this grand narrative, it’s easy to see how and why the organic and biodynamic movements found themselves wrapped into the white supremacy movement from their early stages. These tools provided another facet to center individual purity, and homesteading and the ability to grow one’s own food offered proof of the sovereignty of the individual. The nuclear family was part of the compound as a confederacy. ‘

This mentality hasn’t changed—Justin Rhodes has recently spearheaded a project called “Abundance Plus”, a full-service homestead training program centered on religion and showcasing the work of (coincidentally) only white farmers.45 That’s not to say he’s a white supremacist but rather how homesteading itself, even today, is born from the roots of an ancient tree. On the front page of the website, it reads “You Can Homestead. We Can Help. Inspiration to get you growing. Know-how to get you there. Community to keep you there.” The community online is a way to create a network of homesteads, a digital compound, that doesn’t stop at homesteading but explores homeschooling and other fringe conspiracies.

There’s much more that can be discussed on this subject— in many ways, we’ve only scratched the surface of this narrative. Within this framework, however, we have good reason to steer clear of the conventional homesteader movement and its language choices. I want to be clear, this doesn’t make people who enjoy homesteading bad people; quite the contrary. Their interest in these movements highlights an awareness of the fact that our current system isn’t sustainable, and instead suggests that they are open to alternatives. This offers us real potential to change the narrative and to make meaningful inroads into communities that will otherwise get tied into the alt-right pipeline, and we have a responsibility to step in, when possible.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 33-page chapter, of (so far) an 1178-page book with 823 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episodes #213 & 214, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Lyman Tower Sargent, “Posse Comitatus,” Extremism in America: A Reader (New York: New York University Press, 1995), 343-44.

Morris Dees with James Corcoran, Gathering Storm” American’s Militia Threat (New York: Harper Collins, 1996), 10.

James Coates, “Posse Comitatus,” Armed and Dangerous: The Rise of the Survivalist Right (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988), 105.

“On the campaigns of violence enabled by Klansmen and Columbians (a neofascist organization) who had served in World War II, for instance, see Brooks, Defining the Peace, 60–72. The United Klans of America, the organization whose members would bomb the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four black girls, learned bomb-making from a navy veteran, according to Wade, The Fiery Cross, 321”

“James William Gibson, Warrior Dreams: Violence and Manhood in Post-Vietnam America (New York: Hill and Wang, 1994).”

“Nick Turse, Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam (New York: Picador, 2013); Patrick Hagopian, The Vietnam War in American Memory: Veterans, Memorials, and the Politics of Healing (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), 406.”

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/1998/hate-group-expert-daniel-levitas-discusses-posse-comitatus-christian-identity-movement-and

Barkun, “The Emergence of Christian Identity,” Religion and the Racist Right: the Origins of the Christian Identity Movement (Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 34

Kevin Flynn and Gary Gerhardt, “Alan Berg: the Man You Love to Hate,” The Silent Brotherhood (New York: Signet Books, 1995), 229.

“Louis R. Beam Jr., “Vietnam Bring It on Home,” Essays of a Klansman (Hayden Lake, ID: A.K.I.A. Publications, 1983)”

“FBI clip, FBI report to Assistant U.S. Attorney Hays Jenkins copied to Houston, May 7, 1981, “Klan Gunfire Worries Neighbors,” Houston Chronicle, April 28, 1981, 1, 195; Texas Veterans Land Program, Contract of Sale and Purchase, 8-83244, Louis Ray Beam Jr., Travis County, September 15, 1977, vol. 405, 710, SPLC; Vietnamese Fishermen’s Association, Deposition of Dorothy Scaife, July 6, 1981, Houston, Texas, SPLC.”

Belew, K. (2018). Bring the war home : the white power movement and paramilitary America. Harvard University Press.

“These numbers, drawn from Southern Poverty Law Center and Center for Democratic Renewal estimates, appear in Betty A. Dobratz and Stephanie L. Shanks-Meile, The White Separatist Movement in the United States: “White Power, White Pride!” (New York: Twayne, 1997); Raphael S. Ezekiel, The Racist Mind: Portraits of American Neo-Nazis and Klansmen (New York: Penguin, 1995); Abby L. Ferber and Michael Kimmel, “Reading Right: The Western Tradition in White Supremacist Discourse,” Sociological Focus 33, no. 2 (May 2000): 193–213”

“Mulloy, World of the John Birch Society, 2–3, 15–41.”

“Brad Knickerbocker, “New Armed Militias Recruit Growing Membership in US,”

“Michael Barkun, Religion and the Racist Right: The Origins of the Christian Identity Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996)”

“Somer Shook, Wesley Delano, and Robert W. Balch, “Elohim City: A Participant-Observer Study of a Christian Identity Community,” Nova Religo: The Journal of Alternate and Emergent Religions 2, no. 2 (April 1999): 245–265.”

“The Turner Diaries was first printed in serial in National Alliance, Attack!, 1974–1976, SC, Box 31, Folder 9, and then published as Andrew Macdonald, The Turner Diaries (Hillsboro, WV: National Vanguard Books, 1978).”

“Meg Jacobs, Panic at the Pump: The Energy Crisis and the Transformation of American Politics in the 1970s (New York: Hill and Wang, 2016)”

“GTRC, Final Report, 103, 235; Waller, Love and Revolution.”

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/1998/hate-group-expert-daniel-levitas-discusses-posse-comitatus-christian-identity-movement-and

“Testimony of Daniel Gayman, Miles et al., March 2–3, 1988, Testimonies-1; Testimony of Robert E. Miles, Miles et al., March 29–30, 1988, Box 16-2; Testimony of Michelle Pardee, Miles et al., No. 87-20008 (W.D. Ark. March 14 and 16, 1988), CRL F-7424, Testimonies-1; Testimony of Richard Girnt Butler, Miles et al., March 29, 1988, Testimonies-2.”

“Parties Reject White Supremacist,” Independence Daily Reporter, March 12, 2006, SPLC”

“Louis Beam, “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” Jubilee 7, no. 6 (May–June 1995): 14–15, Ms. 76.10, Box 10-6, HH 4358.”

“Betty A. Dobratz and Stephanie L. Shanks-Meile, The White Separatist Movement in the United States: “White Power, White Pride!” (New York: Twayne, 1997).

James Ridgeway, “Posse Country,” Blood in the Face: The Ku Klux Klan, Aryan Nations, Nazi Skinheads and the Rise of a New White Culture (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1995), 138-42.

Abanes, “Antichrists and Microchips,” 88.

Abanes, “Infiltration of Hate,” 197.

https://rightingamerica.net/the-christian-right-dispensational-premillennialism-and-antisemitism/

Coates, “Conclusion: Apocalypse Now?” 257.

“Pete Peters, The Bible: Handbook for Survivalists, Racists, Tax Protestors, Militants and Right-Wing Extremists (LaPorte, CO: Scriptures for America, ca. 1992–1995), Ms. 76.10, Box 10-9, HH 818.”

“Special Report on the Meeting of Christian Men Held in Estes Park, Colorado, October 23, 24, 25, 1992, Concerning the Killing of Vickie [sic] and Samuel Weaver by the United States Government (LaPorte, CO: Scriptures for America Ministries, ca. December 1, 1992), 26–27, SPLC; Max Baker, “Texas’ New Right,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 18, 1990, page unclear, SPLC; Zeskind, Blood and Politics, 310–316.”

“Zeskind, Blood and Politics, 154,”

“Joe Grego, The Oklahoma Separatist (Inola, OK), issue 4, July–August 1988, 1–17, Ms. 76–72, Box 72-2, HH 2943.”

“Baker, “Texas’ New Right”; “Dear Waco Resident,” from “A Waco Klansman,” Texas Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, ca. February, 1989,”

“Sam Howe Verhovek, “Texas Sect Trial Spurs Scrutiny of Government,” New York Times, January 10, 1994, A10; The Balance, March 1994, back page, RH WL MS 41. See, for instance, “Fight for White Rights!,” White Power: The Revolutionary Voice of National Socialism, Special Introductory Issue, no. 95, 1980, 1, 3, Ms. 76.26, Box 26-1, HH 356; David Lane, “Open Letter to Timothy McVeigh,” Focus Fourteen (St. Maries, ID), issue 601, ca. 1995–1996, 1–4, Ms. 76.72, Box 72-1, HH 4163.”

“Michael J. Sniffen, “Government Ready to Charge Suspect in Atlanta Bombings,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 20, 1998, 8B.”

Ridgeway, “New White Politics,” 188.

Stock, “Introduction: Left, Right and Rural,”

https://www.wgbh.org/news/local/2024-03-26/white-supremacist-incidents-rose-in-2023-adl-says-mass-still-among-hardest-hit-states

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/11/us/politics/veterans-trump-protests-militias.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/18/us/indiana-farmers-market-white-supremacy.html

https://newrepublic.com/article/154971/rise-ecofascism-history-white-nationalism-environmental-preservation-immigration

This is a really great article that dives into the complexity of modern masculinity in an age of less clear expectations: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/07/10/christine-emba-masculinity-new-model/

https://abundanceplus.com/catalog