J. Russell Smith

The name behind Tree Crops, in fact, was far more influential outside of Tree Crops

Farming is a business and it is conducted on either of two systems: the peasant system or a scientific system. .. . I am hoping that thee will be able to follow the golden mean of being a business man and a scientific farmer, as well as a human being.

-J. Russell Smith, writing to his son Stewart.

J. Russell Smith might be the most well-known figure in history in regards to tree crops in North America— largely because of his book “Tree Crops: A Permanent Agriculture”, which has been a foundational text for many people in permaculture and agroecological spaces. While this book is worthwhile for any novice and experience horticulturalist to read, his work expands much further than this one book. In fact, his successes and imprint on industries for generations were so expansive, often working on international or groundbreaking projects in different fields concurrently, instead of organizing this piece on a linear timeline, it will be much easier to understand by clustering in the fields of academic, geography & industry, youth public education, food systems, conservation, and food production. If you’re only interested in tree crops, skip to the last half of the piece, although I think understanding his relationship with geography and education explains why his work in tree crops was so successful.

Let’s start at the beginning. Joseph Russell Smith was born in Lincoln, Virginia, in 1874 to Quakers. Quakerism was a large piece of his childhood and framed his relationship to the land and people around him.1 The Quaker community worked to make their needs serviced by their own community— including working with the poor, addressing disagreements in the community, and more. This was predicated on the meeting house, an active space for all members of the community, which forced the community to be connected, and to create the conditions which reinforced the belief that the purpose of mankind was to help one another and the Earth. In Smith’s own words, “I was born with two or three things. One of them was curiosity. I want to know. The other was a desire to help humanity. . . . Curiosity, helpfulness, and a desire to teach is the true essence of my spirit”.2

His father, Thomas, was a farmer who spent his free time trialing experimental new crops, and in Smith’s words, “The chief thing he did was to find that somebody off somewhere was using a new kind of wheat, and get some and plant it, or a new kind of corn, and get some of it and plant it”. This would go on to be replicated in Smith’s own life as he began to work with tree crops.

Smith’s schooling was also within a Quaker environment—it was only when he was 17 that he attended a school outside of his Quaker town when he spent a year at the Abington Friends School in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania to ready himself for college. Smith’s Quaker education shouldn’t be dismissed, however— the schools he attended focused on scientific literacy & and creating resilience pupils moreso than rigid scripture consumption.3 His interests were in geography, despite his mother’s concern. However, upon enrolling in college, he decided that economics was a more practical career path, and enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Finance & Economy in 1893. His freshman year was the only year he would attend full-time until his senior year, and spent the next five years teaching full-time in high schools while taking classes part-time. In 1898, he finished his final courses, receiving the Terry prize for distinguished scholarship and enrolling in the Masters of Economics program. His career, at this point, was moving towards economics. In his own words:

I had no idea when I graduated from college that I would be anything other than an economist, which was the natural direction of one graduating from the Wharton School with an academic type of mind. . . .

The thing that really made me a geographer was an accidental governmental position. I was going along teaching history and taking graduate study, looking forward to being an economist, when the question arose in the United States Senate: Where shall we build a canal across the American isthmus?4

In 1899 Congress appropriated a million dollars for a commission to investigate routes for a canal across the Isthmus of Panama. Emory R. Johnson, of the Wharton School was chosen as the economist who would oversee the cost estimation of the project, and his student J. Russell Smith was hired alongside him. The unique opportunity not only helped spring Smith’s career as an economist, but the specific role required him to bring his interests in geography into his career.

We floundered like a pair of landlubbers in the mud trying to swim. We wasted time horribly, but we finally came up with a good estimate; . . . our chore in trying to find facts in the literature of 1899 was a tough one. . . . We came out of that job with a firm conviction that the American educational field needed geography in the colleges—quick. Because of our helplessness in the face of a concrete problem, it convinced us that it was extremely important. . . .

I decided I was going to be a geographer. I didn't know if I could get a job in a college, but I knew I could get a job in a high school.

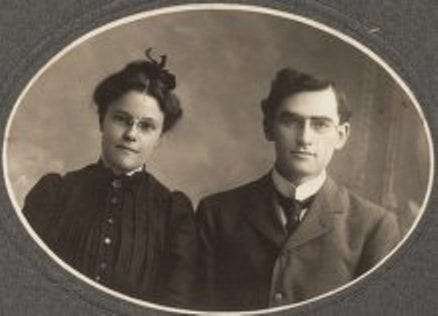

And so Smith’s career path changed again. He left the Wharton School and sailed to New York from Panama, his wife Henrietta (Stewart), whom he’d married in 1898, in tow. The travels would end at the University of Leipzig, where Friedrich Ratzel was busy building the finest geography program in the world. While the program was top-notch, Smith struggled with the language barrier, Germanic cultural customs, and a general feeling of alienation due to his lack of foundational knowledge in geography.

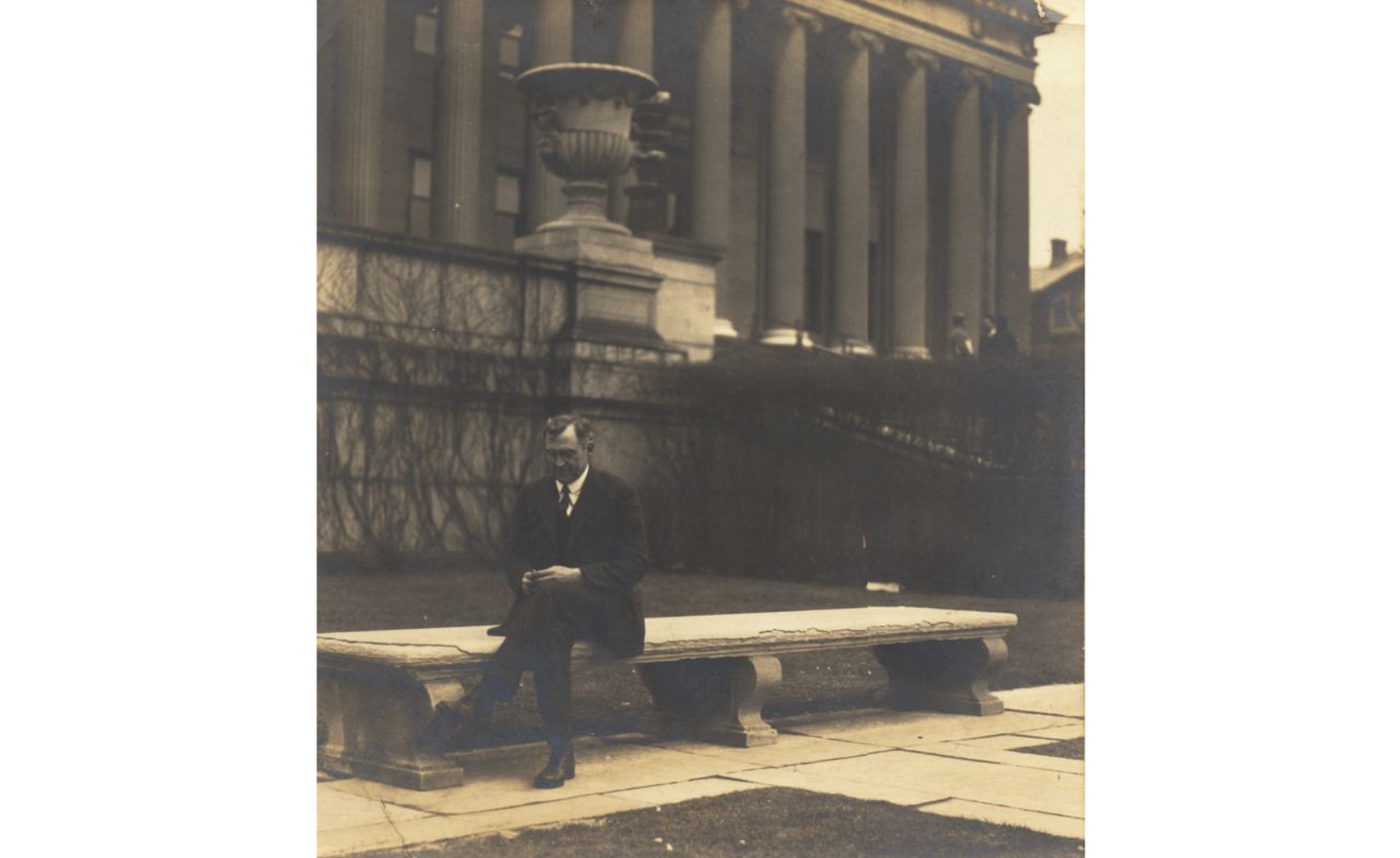

Upon returning from Europe, he accepted a fellowship in economics at the Wharton School for 1902-03, and in 1903 received his doctorate in economic geography. His dissertation, "The Organization of Ocean Commerce," was an applied economic-geographic study reflecting his work with the canal and his time studying in Germany. He was immediately hired at the Wharton School as an Instructor in Commerce, and quickly built the Department of Geography & Industry, which he created and oversaw.

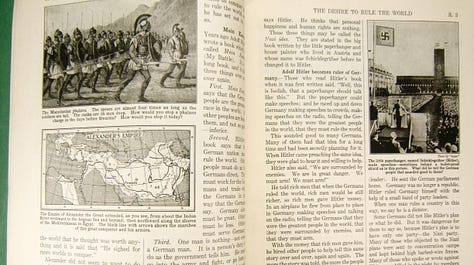

From the late 19th century into the early 20th century, Smith was actively writing and developing a catalogue of economic papers and positions which help us understand his evolution. In his first published paper in 1899, he criticizes American interests in the newly acquired Philippines, arguing that “The American policy of our forefathers is one for us. . . . America is an industrial unit, an economic unit, full of undeveloped possibilities that await the hand of American enterprise. The continent is controlled by the most ingenious of all races, and is dominated by the highest political ideals known to man. What need have we to reach out across seven thousand miles of ocean to take lands populous with millions of barbarians?”5

His racist and isolationist position wasn’t out of place at the time, but we can see this position evolve over the following decades as in later work he advocates for the benefits of people across the globe to further their education and knowledge. The later half of his career is filled with writings of a greater brotherhood of the human race for the general benefit of all human and the non-human world, as we will later see. This was driven partly from changing contemporary politics, from a general maturity, and largely from seeing the global devastation of World War 1.

Bridging the Natural Sciences with Social Sciences

Environmentalism during the early 20th century was a rapidly evolving concept; much of this understanding was framed within a deterministic, human-controlled understanding and not as a complex set of relationships. Geographers were often at the forefront of these discussions, including folks like Isaiah Bowman & British geologist George Barrow, and as we discussed before, this was a period where the idea of permanent agriculture had begun to gain traction. This narrative was still inevitably driven by an economic perspective, and that geography and the biology living on it was directly linked to human activity (or lack-thereof) and altogether was understood at a very crude level. It wasn’t until the work of French geologists Vidal de la Blache and Bernard Brunhes became popular in the United States during this period which the idea that geography and the biology on the landscape was analyzed at afar more nuanced and complex that more detailed research was done in the sphere of geology, leading to far more accurate regional maps & much more.6

In the 1920's the description and analysis of regions became the main focus of geographical writings in the United States. A report of the Conference on Regions of the Association of American Geographers in 1935 was indicative of the thinking of the time that:

The major contribution of geography to the general field of science is the recognition, first, of the ever-varying aspect of the land, and secondly, that, in spite of this variation, the land tends to be divided into areas of more or less similarity. Such areas we call regions.

. . . In geography, the region forms the basis of what is now termed modern or regional geography and has come to be widely accepted as the culminating branch of the subject.7

We can see how this geographical understanding has lead to the concepts around biomes as we think of inter-related biological communities today. As geography during this time began to take on an interactive relationship with the ecosystem, a better understanding of how abiotic features impact and influence biotic counterparts grew and helped further bring together food systems, ecology, and the non-living world beneath our feet.

This was a rather small scope of the world of geography and its purpose at the time, particularly within the United States. Commercial geography was the primary utility of geography, which made sense in a country with vast resources and an economic imperative to find the best way to transform them into financial gain. And this was the chief focus of a young Smith’s work. Much of his work early on was rather unremarkable, but as he developed more comfort in his own writing and beliefs, we see him begin to present ideas far ahead of his time, such as in his work The Economic Geography of Chile, published in 1904, in which he begins to posit arguments about the triangulated relations between man, nature, and geography. In this work, he advocates for the restoration of industries through ecological management, and importantly, through the use of technologies to rekindle the utility and diversity of landscapes that had turned to wastelands.8

This triangulated relationship reflected some of the newer thoughts of the period, and offered a young Smith the opportunity to develop new perspectives on geography, economy, and and the corresponding environment. In his own words, only a few years later in 1907:

We have received from nineteenth-century biology the sweeping truth that organisms are what their environment has made them. . . . Just how much it means for man, for races, and for civilization, we have only begun to realize...

Economic geography is the description and interpretation of lands in terms of their usefulness to humanity. Its net result is the understanding of the relation between the people of a district and their physical environment.

...for the great mass of humanity the geography that is to be of interest will have primarily the human interest.9

His perspective on the relations between human interest and geography caused a stir within the community, and began a new trajectory in Smith’s career. For the next six years, except for the publication of The Ocean Carrier, which in content really belonged to his early commercial period, and several articles on conservation and agriculture, Smith devoted most of his energies to his first major work, “Industrial and Commercial Geography”, which served as a framework for presenting the evolving concept of human use. This book was predicated on a lack of resources for Smith to teach his belief in human-economic geography; he found the existing resources too focused on statistics and static analysis of the physical environment. It was published in 1913 and was an immediate success, receiving praise from other famed geographers (and former students) such as Lester E. Klimm, who called it "probably the first true American college text on the subject." In his preface, Smith addresses the fundamental division that existed with the geographic field in a way that shaped the future of geology and how it would evolve and relate to the fields of agriculture and the future field of ecology, stating that:

This book aims to interpret the earth in terms of its usefulness to humanity. Since the primary interest is humanity rather than parts of the earth's surface, the book deals with human activities as affected by the earth, rather than with parts of the earth as they affect human activities.10

This was the beginning of a new dawn of American geography, which aligned more closely with the work happening in Europe. In the first chapter of the book, Smith paints an optimistic future. Here, the keynote was the importance of the environment to man as well as man's increasing control and use of nature through technological advance. Smith constantly pointed out that technology helped to develop and interrelate the whole world and to equalize differences between areas. Man rather than the natural environment was much more definitely the dominating force, since the main aim of geography was to aid man in commanding the Earth instead of being controlled by nature. Geographic influence replaced geographic response and organic factors became coordinate with the physical landscape.

Smith understood that the limitations that had once guided human relations with the landscape was becoming a relic of the past, for better or worse. In the first chapter, he posits that “The environment of mankind is undergoing the greatest and most sudden revolution that it has ever experienced. It is the change from the local environment, in which the local conditions dominated, to the world environment to which one export commodity admits us and which tends to make us all alike.” His optimism stood in defiance of a society that believed that the best of technological gains were behind us as a civilization. Scientific planning was his answer. Smith felt that negative thinking was not founded on geographic or scientific fact, but, rather, was "due to the shortcomings of our financial and industrial system, and from our . . . purely irrational method of distributing wealth and holding property."

Just as important to Smith in his groundbreaking book was the concept of global mutual aid and cooperation; that through these tools, global peace could help stabilize the country and provide a foundation for resource allocation to parts of the world which needed additional support. Ultimately, for Smith, geography was the bridge between the natural and social sciences.

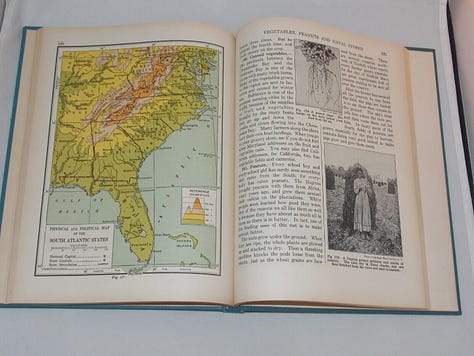

Twelve years later, Smith released another groundbreaking success in “North America: Its People and the Resources, Development, and Prospects of the Continent as the Home of Man”. The significance of the book was two-fold; it addressed the need for regional geographic knowledge at an extent that had not previously existed, and further it provided the first example of attempting to evaluate the continent in terms of human-use organization. Smith’s hope was that the book would help Americans focus their interests and skill development for developing and allocating resources in a sustainable and efficient way. He saw how resources, to that point, had been used in wildly inefficient ways, and felt it was necessary to point out that resources were not, despite the public perception, infinite.

The Economics of Geography

Smith’s work wasn’t just centered in geography, but in the financial world as well. In fact, geography existed primarily as a study to efficiently allocate resources such as minerals as well as to effectively design & fully account for the costs of transportation. During the late 18th century, during both his undergraduate years and later his time doing his PhD at the Wharton School of Finance & Commerce, Professor Emory R. Johnson was busy working to build the Geography program which Smith would later manage. The Wharton School was barely over a decade old, and held fast to an ethos which advocated for experimentation and research in new fields, making it an outlier at the time, and one of the only schools to offer a four-year degree in finance & commerce.

In 1903, while working on his doctorate, Smith took over teaching much of the geography at the school, and tailored the curriculum to his content knowledge. Two general tendencies soon became evident in Smith's developing courses just as they did in his writings that grew from the courses and, in turn, stimulated them. These were the increasingly human-geographic nature of the material and the broadening of the scope of human geography. Particularly significant was "Resources of the United States," which became his basic and best-known course in economic geography at Wharton and a requirement for all freshmen. It brought to life the dynamic theme of the intimate interrelationship between man and nature. In this course, Smith clearly portrayed the great industrial opportunity of the United States when accompanied by modern technology and a progressive socio-economic philosophy.

For the next decade, Smith thrived in academia, expanding his course offerings, training future professors and leaders of industry, and further exploring the interconnectedness of geography, economy, agriculture, and industry. This led to the release of a number of books which attempted to bring the duality of nature and man to the industrial field, “The Story of Iron & Steel” in 1908, which advocated for creating economic systems which were safe, ethical, allowed for labor bargaining power, and the development of garden cities whose goals were to make slums materially impossible. This came out before “North America”, and we can see how quickly his evolution had transitioned from his early years in college and graduate school.

Despite general feedback critiquing his teaching style as boring and that his lectures with a slight lisp became tiring, his depth of knowledge and excitement at the graduate level garnered many men who would later become major figures in the business world across the 20th century.

In 1919, Smith transitioned from Wharton to Columbia, both because of the request of Columbia’s school president Nicholas Murray Butler who offered him a role overseeing the Department of Economic Geography, the first of its kind in the nation, as well as the refusal of the University of Pennsylvania to pay his ten assistant students.11 Further, the University of Pennsylvania had fired one of his good friends, one that would go on to play a major role in the world of permanent agriculture decades later, Dr. Scott Nearing, for speaking out against the rich. Smith is quoted saying that “I regret more than I can say the dismissal of Dr. Nearing. It is not a personal matter; it seems like a notice to all of us. Many of us feel as if we would like to resign this morning. This is only a matter than can make the majority of men feel like that. What kind of a man do they want anyway? Nearing was one of the most efficient men in our faculty… We feel that we are puppets. Must individuals refrain from doing what they believe to be their duty?”. 12He resigned shortly later.

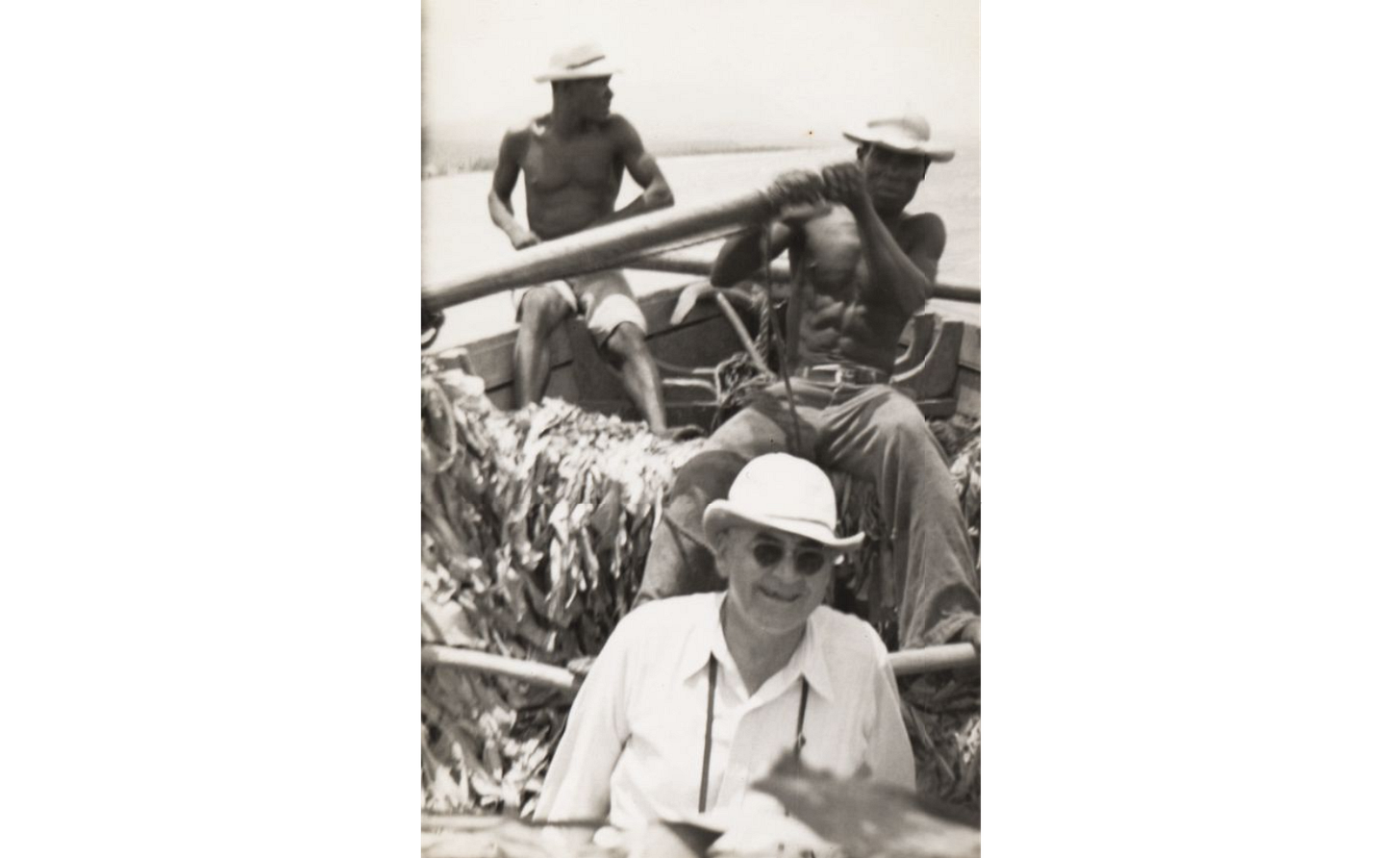

It was here that Smith was able to make not just geography but his flavor of geography a respected field with graduate and later PhD programs which were quickly mimicked across the country, due to Columbia’s prestige. The program developed was a labor of love for Smith, and afforded him a unique opportunity in his career to leverage his successes to focus primarily on field-based work and writing instead of full-time instruction. It was in this traveling which Smith was exposed to landscapes across the globe with destroyed topsoils which he felt could be restored with tree breeding programs.

J. Russell Smith & Public Education Innovation

With the full support of Columbia, Smith’s ability to work on textbooks, travel, and other research expanded significantly. One are of particular interest to him was writing children’s books on geography. From the beginning, Smith's educational aims in writing elementary texts were in terms of social values and general education. As he repeatedly stated, "The chief function of geographers is education—the education of people who are not geographers and never will be geographers."13 His goal was specifically to help children understand their place as “world citizens” and to understand interdependence across nations and to humanize people from far-off countries by exploring the ways geography and humans influence one another.14

The recent World War had a profound effect on him and his understanding of interdependence. Smith believed that "the elementary school is the place where geography may render its greatest service to modern society," as this would be the place where a child would first be introduced to both their own country and the rest of the world. It was only through respect, understanding of our interconnectedness, and through empathy which international peace would thrive in an age of increasingly powerful weapons.

Within his books, he emphasized the relations between humans and their environment, believing that by focusing on common needs and problems across the globe, children could more readily develop in sympathy and understanding towards others. With his two decades of teaching, he was able to carefully provide facts which children could apply in their everyday lives, reinforcing the fundamentals of geography by using examples that were concrete and accessible in simple language. He credited his wife Henrietta for assisting him in this endeavor, as she was a elementary school teacher.

Smith was also one of the first writers of elementary geography texts to correlate geography with history and the other aspects of the social sciences. This approach enabled students to see the evolution of human relationships with their environment, and to more importantly project that into the future. It showed the great changes wrought by scientific discoveries which have enabled man to make fuller use of his environment. Smith contextualized geography in relation to good citizenship, community-mindedness, and conservation.

Alongside his books were a number of exercises and teaching materials for educators who wouldn’t have a background in geography to otherwise deliver the content. This material was provided for free for teachers, aligning with Smith’s greater concerns for public education.

Consistent with his concern for the welfare of the general public and his continuous pioneering work, Smith played a prominent part in the 1933 meeting of the World Federation of Educational Association & the National Society for the Study of Education inDublin, as chairman of the Department of Geography. The theme of the group he chaired was the "mutual appreciation of peoples", a far cry from the young man who wrote about the barbarians of the Philippines.15

In his work for children, specifically the Human Geography series, highlighted how communities learned to live within the geographic (including climactic) conditions within a region, gearing their food and industry systems to those conditions. These books numbered extensively for kids at different reading levels and for different places, all with extensive resources for teachers to assist their students’ education, ending at the Junior High School level.

Along with the Human Geography series, Smith developed another collection called “Our Neighbors” which emphasized the need to understand our global neighbors, once again reinforcing the importance of interconnectedness, empathy, and understanding. The 1920’s and 30’s kept Smith busy working to build the tools to prepare children for a better future, but he was also investing more and more time in the concepts of permanent agriculture and tree crops.

Smith the Food Systems Leader

Smith had always had an interest in food systems, largely because of his agrarian background. During the first World War, Smith started getting involved in local food projects in Pennsylvania. In April, 1917, a committee on agricultural service was formed at the University of Pennsylvania. Smith was elected chairman and in two weeks' time had three hundred boys working as farm volunteers in various states.16 From April to November, 1917, Smith served as chairman of both the Food Commission of the Philadelphia School Mobilization Committee and the Food Section of the Mayor's Home Defense Committee. In that same year, he began writing articles for Country Gentleman Magazine advocating for a national food conservation campaign.17

Like many, World War 1 radically altered the trajectory of Smith’s life. His background in geography and commerce made Smith a valuable man in the eyes of the State; the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace requested a study from Smith on the impacts of global trade from the war, and in 1918 he requested a leave of absence from Wharton to become a special trade expert in the Bureau of Research of the War Trade Board in Washington. His return in 1919 coincided with his decision to leave Wharton, as we discussed earlier.

World War 1 reinforced Smith’s beliefs about the need to leverage trade for international peace, and that the United States wasn’t working to effectively take advantage of quickly becoming the world leader in trade due to the destruction of Europe. It also refocused much of his energies towards food systems and food crops, manifesting in the 1919 book “The World’s Food Resources”, as he became increasingly uneasy about the ease of which food supply chains could be easily disrupted. Unsurprisingly, he framed the question food security and food resources within the question of human interdependence; that without healthy social institutions and without global cooperation, famine would eventually reach the shores of every nation. His proposals were both visionary at the time and concerning in reflection. Smith suggested we drain the swamps of the southeastern United States, as they were the last forms of cheap, arable land, as one of many examples of ways to increase arable farmlands.

In this same book, he also projected China’s future growth as an manufacturing center which would possibly surpass the United States, and that the U.S.S.R.’s future was reliant on its ability to increase and distribute what its grain belt could potentially produce.18 In general, Smith was optimistic about the potential for civilization to produce foods through new petrochemicals, breeding work, conservation practices, and undiscovered scientific breakthroughs.

The Great Depression & Tree Crops

“Agriculture is usually symbolized by a picture showing a man, a plow, and a sheaf of wheat. I would make the symbolization double by adding to it some kind of nut tree in fruit. I have long had a vision of waving, sturdy, fruitful trees yielding nuts and other valuable fruit, and standing on our hilly and rocky land where now the gully and other signs of poverty, destruction and desolation gape at us. This vision of the fruitful tree also extends to the arid lands, there also vastly increasing out productive areas. Beyond a doubt the tree is the greatest engine of production nature has given us, and in its ability to yield harvests without soil injury on rough, rocky, and steep lands, and on arid lands, carries the possibility of the approximate doubling of the area of first-class cropping land in the United States, also probably in many other countries.”19

Smith and the other contributors maintained that big business needed reorganization in the form of more ethical practices, scientific management, and a de-emphasis on the profit motive, in order to bring about a greater degree of social justice. The pamphlet was particularly critical of the government's policy of scarcity economics which Smith believed caused hunger and want in a land immensely rich in natural resources and industrial potential.

The fundamental questions of scarcity economics and government regulation were again the themes of Smith's later book, “The Devil of the Machine Age”. The "devil," Smith said was the fallacious doctrine of scarcity in order to keep prices high, on which the whole world economic structure was being built.27 By following this doctrine he feared that the country would go from bad to worse in the direction of poverty, inequality, oppression, complete government control, general social disruption and perhaps even war. Smith was highly critical of the temporary devices of the New Deal, such as limited production goals, price fixing, wage stabilization, federal subsidies, nonproductive W.P.A. projects, doles, plowing under, government payments for failure to produce, and pump priming. He described these measures only as a succession of "idiocies" perpetrated by bankers, industrialists, merchants, farmers, and virtually all classes and sections of society for the purpose of establishing scarcity.28 Instead, Smith advocated in The Devil of the Machine Age an economy of abundance in which the country and the world might learn to stabilize itself in terms of the resources which the world as a whole could provide. In place of the scarcity system where "everybody is trying to get better off at the expense of everybody else," he wished to see more harmonious social and economic system. Therefore, he again proposed consumers' cooperatives, producers' cooperatives, consumer organizations for protection, private business run for a regulated fair profit, government operation of some enterprises such as public utilities, and nonprofit private foundations. Although some of his remedies may seem over-idealized, his advocacy of an economy of abundance was considered by many to be fundamentally sound. Looking at the situation realistically, he believed that American businessmen faced an ultimate choice; they could make an economy of abundance within a reasonable profit system and on an ethical social order, or else they might end up one day handing over all business to the government.

While Smith had socialist sympathies, he was hesitant about handing power over to the government. For example, as chairman of the subcommittee of the All Friends Conference of 1935, he guided the preparation of a pamphlet entitled Methods of Achieving Economic Justice.20 It was subtitled "A syllabus for those concerned to act in the light of knowledge." Its text and annotated bibliography dealt with such items as scarcity economics in the midst of abundance, a declining standard of living, and America's capacity to produce and consume. Its aim was to provide information on these and other topics and to present a program framed within Quaker values. Among the important points that Smith and his fellow committeemen advocated were economic internationalism, a decent minimum standard of living, self-help cooperatives, a decrease in federal regulation, and a weakening of the power of the rich through stricter antitrust laws and increased taxation. Smith and the other contributors maintained that big business needed reorganization in the form of more ethical practices, scientific management, and a de-emphasis on the profit motive, in order to bring about a greater degree of social justice.

In the midst of the Great Depression, Smith found himself rethinking the future of food systems. While he had always valued trees and their role in ecosystem resilience, as experienced on his own father’s farm, it was when he traveled the parts of Europe where traditional farming practices were still in place— from olive groves with crop understories in southern Europe to the pigs which grazed beneath the oaks on the Iberian peninsula. During the 1920s he had traveled across the globe, including in the early 1920s during which he had visited the Soviet Union to help deliver famine relief with then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, and was horrified by what had seen.21 In response, he then traveled across the United States in search of examples of tree crops and their uses by farmers, which was translated into the 1929 groundbreaking “Tree Crops”, the reason you’re probably reading this piece on him. He describes, for example:

Syria is an even more deplorable example than China. Back of Antioch, in a land that was once as populous as rural Illinois, there are now only ruin and desolation. The once prosperous Roman farms now consist of wide stretches of bare rock, whence every vestige of soil has been removed by rain.22

It wasn’t as though he had just recently stumbled onto the concept of tree crops and permanent agriculture. In 1900, he had bought 130 acres in Sunny Ridge to experiment with the concept. The land had already been occupied by black walnuts and chestnuts, and allowed him to experiment had have space to plant new, improved varieties as they were rediscovered. Over the next 51 years of his occupancy, this farm expanded to over two thousand acres with over 100 documented varieties of nut and other species. These trees, many of which he bred himself, supported sheep, pigs, and cattle.

His breeding work was predicated on finding the best trees that were not named , but rather were simply recognized in areas as providing the best masts, thinnest shells, sweetest nuts or fruits, and so on, much of which was the work of indigenous people that otherwise would be lost. Smith also conducted contests either on his own or in conjunction with organizations, in order to find superior scions and to awaken interest in crop trees. He publicized the contests extensively by writing to agriculture departments of colleges, local farm journals, and newspapers. Walnut contests in 1931 and 1932, for example, provided much information for the Northern Nut Growers Association, which was then attempting to build a new industry around these trees as well as the hickory. Smith's largest number of contests were those for the honey locust, which he ran periodically from the 1920's until World War II. The first contest brought in pods with 25 per cent sugar. Later ones brought in record beans analyzing as high as 35 per cent sugar, many of which are the basis of the cultivars in production today. The wide range of the trees from the deep South to as far north as southern Minnesota was also discovered.23

Smith tested and developed new strains of pecans, hickories, black walnuts, English walnuts, and blight-resistant chestnuts, as well as honey locusts, pawpaw, mulberry, and persimmons. Practicing what he preached, he ran his farm as a business, not a hobby, and became recognized as a commercial breeder, selling the lines of trees he bred and grafted at scale.

While his interests in breeding varied, one of his key areas of focus was on restoring the American Chestnut through breeding work with the Chinese & English Chestnut, working alongside the United States government in this endeavor. He began to experiment with the original stand on his farm and by 1912 he had a large orchard of American and English chestnuts. In that year, the chestnut blight struck Virginia. To try to control the blight, the experiment station at Beltsville, Maryland, made arrangements with Smith to use his orchards as an experimental center for sprays. The work was unsuccessful; but Smith continued his interest in the chestnut, and in the 1930's he discovered a blight-resistant Chinese chestnut and other strains immune to the disease.

While chestnuts were the nut crop he cherished the most, the honey locust was the fruit crop— if you could call it that— which he found most interesting. In 1923, W. J. Spellman and Assistant Secretary of Agriculture, Willet Hays, encouraged Smith to work with this promising tree, which Smith would later call a “real sugar tree”. Why the honey locust? It was native and extremely hardy; it was exceedingly prolific; it was highly nutritive as animal fodder and as a possible food for man; and its sugar content of more than a third made it equal to the best sugar beets and better than the yield of the richest crops of sugar cane.

Part of Smith’s method was to prove the tree crops collected weren’t just novelties, but to show how these crops would work in a profitable system. This involved multi-layer cropping (what he called ‘two-story agriculture’), alley cropping, mulching tree crops while operating a no-plow system, and multi-species grazing under mature trees.

Smith also leveraged his extensive writing & educational background, which is showcased in “Tree Crops”. Reading this book highlights how Smith focuses on presenting crops not as novelties but rather as substitutions for crops that people are already familiar with. For example, chestnuts are treated as a tree corn, honey locust as a stock food, with future applications as a perennial sugar crop, and so on. Early on in the book, he stresses the need for “Institutes of Mountain Agriculture”.24 Ultimately, his vision was that these institutes would be a response to the need and demand of tree crops while being regionally specific. John Hershey's forest, which you can read about here, was a model of what Smith felt was needed across the country. He was indifferent about how these institutes would be held or organized— they could be maintained by government agencies, philanthropic involvement, or even private business. The pivotal point was that an integrated network of specialists continued to expand on the experimental work he and his friends were doing.

In 1953, Smith released a revised version of this book, which provided updates on tree crops that he discussed in the original volume and used his newfound name recognition to criticize the government’s abandonment of permanent agriculture in the post World War 2 era, which we discussed at length here.

The New Deal Smith

While Smith was critical of the Roosevelt administration and its handling of food production, specifically around artificial scarcity, his work was well-recognized by the administration and its team, leading to Roosevelt offering Smith the role of Secretary of Agriculture under his administration, which Smith declined.25 His farm was used as a model for much of the policies the Soil Conservation Service advocated and which folks like Russell Lord wrote about to get the general public on board with a new vision of agriculture.

Smiths’s farm and his writing became so significant in the evolution of the Roosevelt administration’s policies that his farm was used as a model for the Tennessee Valley Authority’s work under Arthur E. Morgan, and Smith personally recommended John Hershey to oversee the experimental crop farm under the TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority).26 Smith worked closely with Hershey during his time at TVA, and often pointed to Hershey’s farm in Downington, Pennsylvania as a model of future tree crop projects. Hershey and Smith worked so closely on the TVA projects that much of the breeding stock that was the basis of the TVA tree breeding projects were from Smith’s own farm. When Hershey left in 1937, the project, like many permanent crop projects of the early 20th century, was abandoned by the government, which Smith very publicly criticized.

Smith’s interests weren’t just focused on tree crop breeding simply for future food prospects, but also for conservation reasons. Flooding and poor river stewardship was a chief concern of his, from the massive Mississippi to the Rio Grande, which he called “one of the most perfect examples of regional suicide to be found anywhere in the world.”27

Collaboration is Key

Starting early on, Smith refused to work in a vacuum. From his collaborations with John Hershey regarding finding and propagating unique cultivars of tree crops to formalizing partnerships, Smith was always eager to collaborate and learn from other folks. One of the organizations that Smith found most helpful in his work was the Northern Nut Growers Association in which he was particularly active until the 1950's. This unique society was founded in 1910 "to promote interest in nut-producing plants, their products, and their culture.” The membership was open to all interested in nut trees and included tree lovers from all walks of life. Smith joined the group in 1913 to learn new methods of grafting walnuts. A never ending source of energy, he considered their activities so valuable that he became an active member and in 1916 was elected president.

The proceedings of their meetings tell much of what Smith was doing at Sunny Ridge, since he invariably read a paper before meetings of the group. These journals are still available online, even on Amazon as digital copies, and are a trove of information that has yet to be fully brought to light. They also provide some insight into the logic behind his work. For example, in the 1946 edition, Smith states that they need to “Urge the members to run local contests for good nuts. It may bring members if not nuts, and you may find some good new neighbors you didn’t know about”. A few years later, for example, he describes the Butternick Pecan which he had planted decades prior and had described as a “non-fruiter”. Only in 1951, when digging them up after selling his farm, had he noticed the ones he had given to a neighbor were producing high-quality pecans with consistent crops.28 Those trees, among others from his farm, may still stand in Hamilton, Virginia.

Smith was also interested in the American Genetics Association. He occasionally wrote for their publication, The Journal of Heredity and ran several nut tree contests with their cooperation. In general, government agencies neglected tree crops prior to the Roosevelt administration, and even that was minimal. However, two experiment stations of the United States Department of Agriculture are worthy of note for their creative work. One is the Horticultural Research Branch at Beltsville, Maryland, and the other is the Southeast Experiment Station at Waseca, Minnesota. Smith worked closely with specialists at these stations, particularly around the American Chestnut.

Later in life, Smith become very active in the organization Friends of the Land, founded by Russell Lord, which was centered around soil and water conservation. In fact, the 1953 edition of “Tree Crops” was sponsored by Friends of the Land.

In 1956, a decade before his death, Smith was awarded the Cullum Geographical Medal for his work in geography, conservation, and college course development. Despite his reputation today around tree crops, Smith his recognized as one of the most influential geographers in American history. While Smith’s notoriety and influence is worth exploring, his story is also worthwhile simply for his capacity to create change and influencing public narrative despite being largely self-taught in agriculture, conservation, genetics, and geography. Yet, despite this “self-made” character, his lived experiences taught him cooperation and interdependence were a crucial piece of success for not just the country but for the planet as a whole. This underscored all of his work; how can we leverage our incredible capacity as humans to make an equitable world? Smith died at the age of 92 on February 26, 1966.

While this piece is expansive, it’s worth noting that the J. Russell Smith archive is full of non-digitized records and correspondence of Smith’s. And, of course, the older copies of the Northern Nut Growers Association. I highly, highly recommend, if you’re looking to explore nuts in your area that might have been part of a breeding project, accessing these journals through Amazon or another online source where they are digitized and searchable. You’ll find many names that were significant in breeding projects that are now long forgotten, names like Dr. Robert T. Morris & F.N. Fagan. There’s much research to be done, and for folks who want to get involved and have no access to land, research is necessary for us to find lost cultivars. This can mean digging through the journals from that time, identifying folks who were involved and which were near you, and tracking down the old farms that were once home to many of these trees. Often, these farms have been turned to subdivisions by later generations, but some of these trees may still exist. Joining the Northern Nut Growers Association is also a great way to connect with folks and find where leg work needs to be done in your area.

Further, I have no doubts there’s more information on Smith and in particular around tree crops that’s worth highlighting here; please don’t hesitate to reach out with additional information (ideally with some kind of source) so this can be a one-stop resource for folks looking to learn more about Smith’s contributions to tree crops in particular.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 32 page chapter, of (so far) a 562 page book with 243 sources, you can support our work a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content (which has not been released yet), the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can subscribe on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Brinton, H. H. (1997). Friends for 300 years: The history and beliefs of the Society of Friends since George Fox started the Quaker movement. Pendle Hill Publications.

Rowley, V. M. (1964). J. Russell Smith, geographer, educator, and conservationist. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Brinton, H. H. (1967). Quaker education, in theory and Practice. Pendle Hill.

Interview with J. Russell Smith, July 14th, 1953.

Smith, J. Russell. "The Philippine Islands and American Capital," Popular Science Monthly, LX (June, 1899).

Sauer, Carl. "The Survey Method in Geography and Its Objectives," Annals of the Association of American Geographers, XIV (March, 1924).

Hall, Robert Burnett. "The Geographic Region: A Resume," Annals of the Association of American Geographers, XXV (September, 1935), 122-23.

Smith, J. Russell. "The Economic Geography of Chile," Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, XXXVI (January, 1904),

Smith, J. Russell. "Economic Geography and Its Relation to Economic Theory and Higher Education," 1907.

Smith, J. Russell. Industrial and Commercial Geography, 1913.

Square Deal, Volume 1, Number 7, 26 June 1915.

https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TSD19150626&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN--------

Smith, J. Russell. "Are We Free to Coin New Terms?" Annals of the Association of American Geographers, XXV (March, 1935), 19.

Smith, J. Russell. "What Shall the Geography Teacher Teach in the Elementary School?" Journal of Geography, XLVI (March, 1947).

Proceedings of the Fifth Biennial Conference of the World Federation of Education Associations (Dublin, Ireland: World Federation of Education Associations, 1933).

War Services of the Members of the Association of American Geographers," Annals of the Association of American Geographers, IX (1919), 67.

The three articles referred to are: "Shall the World Starve?" Country Gentleman, LXXXII (June 9, 1917), 3-4, 24; "Why We Hate the Food Speculator," Country Gentleman, LXXXII (June 23, 1917), 1-2; "Quit Fooling and Talk Sense," Country Gentleman, LXXXII (August 4, 1917),

Smith, J. Russell. The World's Food Resources (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1919).

Smith, J. Russell. “President’s Address” Northern Nut Growers Association, Report of the Proceedings at the Seventh Annual Meeting Washington, D. C. September 8 and 9, 1916.

Smith, J. Russell, et al., Methods of Achieving Economic Justice (Purcellville, Va.: Blue Ridge Herald Press, 1935).

Starkey OP (October 12, 1966). "Memorials: Joseph Russell Smith, 1874 – 1966". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 57 (1): 198–202. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1967.tb00598.x. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

Smith, J. Russell. Tree Crops (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1929), p. 189.

Smith, J. Russell. "Tree Crops, An Unappreciated Possibility," BioDynamics, III (Summer, 1943), 38.

Smith, J Russell. Tree Crops (1929), pp. 8-20.

Interviews with Professors Klimm and Willits, who believed that the above was true. Smith made no mention of the subject in interviews with biographer V.M. Rowley.

Hershey, John W. Tree Crops and Their Part in the Tennessee Valley (Knoxville, Tennessee: Division of Forestry, Tennessee Valley Authority, undated).

Smith, J. Russell. "Plan or Perish," Soil Conservation, XIV (October, 1949), 71.

Northern Nut Growers Association Report of the Proceedings at the Forty-Second Annual Meeting Urbana, Illinois, August 28, 29 and 30, 1951