Navigating Climate Change: The Turkana People's Adaptive Strategies in a Shifting Landscape

Arid agriculture, pastoralism, and communalism feed resilience

Lake Turkana is an anomaly— it’s the world’s largest desert lake, and its water is too alkaline & saline to be used for drinking or irrigating crops. However, that’s only one part of its story— while fishing has remained an important part of Indigenous living, it once was a far more hospitable ecosystem, and the evolution of the lifeways of those who inhabited the region is a source of inspiration, given the current climactic changes. Historically, the people who had stewarded this land call themselves the Turkana.

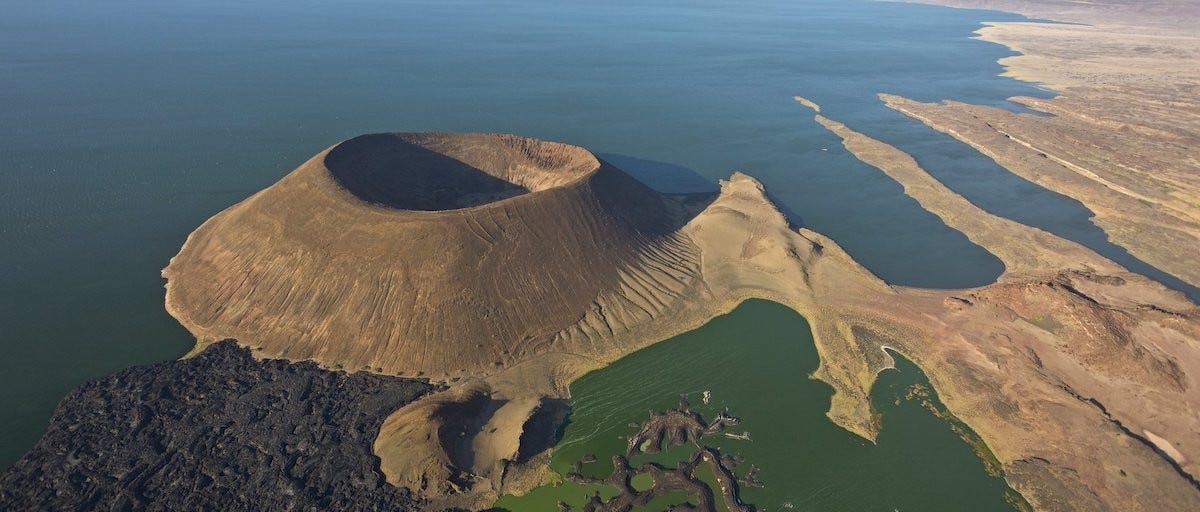

We’ve focused most of our time so far looking at groups that live along the oceans, primarily at the bottom of mountains, and a large part of that is because those regions are easily farmed because of the natural tendency of lowlands to receive the nutrients from the hillsides. This piece will highlight a very different history. For context, if you’re not familiar with Lake Turkana, it’s in modern northwest Kenya. Lake Turkana is unique in a few ways; the first is that it’s a saltwater lake— the fourth largest saltwater lake in the world— meaning the water isn’t drinkable, and not only this, but the lake is the world’s largest alkaline lake, as we had mentioned, also known as a soda lake. This means the lake is extremely high in pH, which causes a lot of interesting things to happen to the biology, primarily that the biology is more active and diverse than in traditional lakes.

Before the arrival of domesticated animals in the Lake Turkana region, human subsistence was focused on exploiting aquatic resources. This is exemplified by the so-called “Bone Harpoon Cultures,” dated to around 6000 BC, but they likely span additional millennia before and following this date.1 All of these occupations were tied to a previous history when the lake stood at least 100 feet above its current height, and had more water flow with the Nile River, probably neutralizing the lakewater and allowing for more use of the lake itself, and probably speaks to a time with a more humid climate, suggesting forests had once stood in these regions.2 After 2000 BC, the subsistence economy shifted to cattle and caprine herding— meaning a goat or sheep or a possible predecessor of the two.

There’s something really interesting about the timing of this region drying out. This is the period during which Egypt had fallen under Roman rule. We haven’t gotten to it yet, but Rome has greatly impacted modern agriculture. I can’t help but wonder whether this may have been one of the first cases where modern agricultural methods caused a massive ecological disruption. It’s a conversation for another day, but something to think about.

Further, it’s important to recognize that, like in Japan, a volcano sits along the edge of the region, having left at some point extremely fertile soils for vegetation, so what we see in this region is a community that lived in the region for its richness and learned to evolve as resources became more and more sparse. Often, the question that seems to come up when we talk about people who live in arid, extreme climates is ‘why’? And most often, it’s because the climate has not always been the way it is today. With this, we can watch two different types of farming exist on the same land under different landscapes, both able to host humans who can improve the landscape.

For this piece, we’ll spend some time looking at before and after this change in the climate, as nothing is known about the time during the changes in the climate. During the more tropical time around Lake Turkana, the Turkana people primarily hunted small game, were semi-nomadic, lived heavily off of the fish in the ponds, and preyed on ostriches for their eggs.3

There is evidence of both fishing—primarily tilapia— foraging and even pastoral subsistence during this time including versions of cattle, camels, and caprine, as well as even bones of domesticated donkeys which suggests intensive farming or land management may have been taking place, but little there’s little evidence that points to that as an extended practice. Most evidence points to the idea that the Turkana were not uniquely skilled at one type of cultivation but instead were organized as a jack of all trades, in that they were capable of going after whatever in their environment was available at the time.

The change from this tropical-like climate to the arid conditions can be seen using deepwater sediment cores and reflects nearly a 900-year transition to the climate of the region today.4 Today, the rainfall patterns and distribution are unreliable and erratic, with an annual average of 17 inches. For context, today, in the United States, the average rainfall across the country is around 32 inches. The daily temperatures in the region today range from 75 degrees F to over 100 degrees F.

When we talk about these kinds of unique climates, the climate, and ecology cannot be understood in isolation from an understanding of the pastoral society and the management of their livestock. Neither humans nor livestock could survive in arid areas without the other. To maximize the use of land there are several strategies that the pastoralists have developed over the years. These include, among others, keeping more than one sort of livestock, dividing livestock holdings into spatially separate units to minimize the effects of localized droughts, and the establishment and the maintenance of a special system of resource sharing, lending, and giving of gifts to relatives and kinsmen within and outside the clan.

The Turkana keep a variety of animals for grazing, including cattle, camels, goats, sheep and donkeys. This is in response to the diversity of the forage resource, ranging from large trees to woody bushes and shrubs, perennial and annual grasses and herbs. Here diversification helps reduce the risk of loss should one or other stock type suffer. Further, it acts as an optimal means of exploiting the vegetation resource on a sustainable basis. Such mobility and livestock diversity is necessary for making maximal use of the forage resources as well as reflecting the diversity of the plant community. Amazingly, the animal makeup is still similar to what animals they had managed in a completely different landscape thousands of years ago.

Many of these local pastoralist communities practice shifting agriculture. Shifting cultivation consists of a complex system of landscape exploitation that is linked to traditional land tenure rights such as sorghum gardens, where the Turkana cultivated 17 seed varieties of sorghum and tree management.5 To cope with unpredictable floods, the Turkana staggered cropping patterns at different times and in varied micro-topographic types (similar to the domestication practices of the Eastern Agricultural Complex in the modern United States). What this means is they often created a multiplicity of crops at different topographic heights so that no matter how high the flood waters got, at least a handful of paddies would receive exactly the amount of water and nutrient dump they needed to grow plentifully. Farms were utilized rotationally, and often would be left to go fallow for five years or more, and in some cases were even abandoned for generations, and all of these decisions were based upon the landscape.

The traditional shifting sorghum cultivation in the river floodplain has three important features. First, they created agricultural landscapes of different ages that shifted between active, fallow, and forest landscapes. Secondly, sorghum-farming landscapes are closely associated with forest landscapes that are used for livestock browsing. Thirdly, in establishing sorghum gardens along a river channel, the Turkana selectively cleared young trees, while saving mature trees. One study even shows the positive role played by sorghum-shifting agriculture in forest regeneration, implying that farming promoted ecosystem diversity by creating highly heterogeneous vegetation in the floodplain.

The Turkana have had a strong tradition of sorghum gardens which are planted during the rains and if harvested will help supplement the pastoral diet. These gardens are usually found in naturally inundated areas either close to a river or in a natural depression and constitute a traditional form of water harvesting. Those gardens close to the river may be of two types, those at the high flood level where the soils are better but cropping is more risky, and those near the river where the crop could be washed away. Such gardens are individually owned and usually farmed by the women and are found close to the wet-season livestock grazing areas.

Farm areas showed significant differences among farming landscapes of different ages, but not between the active and fallow farms. What this means is that, while the farms impacted the landscapes, the landscapes didn’t ‘revert’ back to a natural state the way we think of, say, the woods reclaiming an old farm.6 The interaction between active and fallow and farming landscapes of different ages was significant. Woody species richness showed significant differences between farming landscapes and active and fallow farms.

Despite this, on average, the fallow farms had greater woody species richness than the active cultivation. This points to another interesting nuance in how the landscape is managed. Actively cultivated farms were outright eliminating certain species from their landscapes, which returned after the landscapes were no longer farmed. Yet, old and very old farming landscapes had significantly greater species richness than the landscapes of recent and middle periods, although differences were not significant between old and very old; and between recent and middle.

There are a few reasons why greater species richness may exist in the oldest landscapes but not the newer landscapes, despite it seeming contradictory. Likely, species that were not favorable weren’t necessarily bad, but the other species were slower growers so they had to be thinned. Once the slower-growing species reached their maximum height, allowing the fast growers to compete was no longer risking the survival of the primary species. If they were clearing out those fast-growing species, they had likely found a use for them, and that use can be magnified when utilizing a tree that doesn’t need to be cut down to be used.

Further, this woodland regeneration is linked to livestock browsing and bank floods. After feeding on Acacia pods, the livestock, especially goats, dispersed the ingested seeds and facilitated forest regeneration, which was then sustained by the floods. The link between farming and forest landscapes and livestock grazing more than other management practices encouraged the Turkana pastoralists to conserve the floodplain woodlands.7 The very basic huts built for livestock were often fan leaves with branches tied together, would quickly fall apart in a matter of decades and would be overrun with acacias springing from the manure of the animals and the shade of the hut which provided the ideal conditions for the trees to thrive.

Secure tenure over land and trees, or clear rights to their use was of crucial importance as an incentive for the Turkana to manage and maintain their resources and is a part of this semi-communalist system of access to grazing and trees, predominantly known as Ekwar. Ekwar is the ideology that gives the individuals in the community the right to use the trees as they see fit as long as they do not kill or harm the trees themselves. However, such rights are complicated by being three-dimensional in terms of people (the Turkana pastoralist), time (the pastoralist's ability to maintain the necessary links to keep his Ekwar), and space (the area covered by the Ekwar).8

The term Ekwar literally means that area beside the river bank, but it also implies a degree of flexibility that is hard to quantify since it is time and context specific. An Ekwar is strongly associated with ownership of the trees (or more particularly their produce) beside or near a river (or in some instances lake). It is of particular importance during the dry season when a person's Ekwar will provide the family with valuable dry season fodder in the form of pods and leaves from various trees, in particular, Acacia tortilis. The produce from the Ekwar belongs to the owner and no one else can use it unless by prior arrangement and agreement. Where an Ekwar owner is absent for a period of time and not using the produce of his Ekwar, it is likely that someone else will take it over so that the produce of the Ekwar can be used efficiently. Such flexibility of Ekwar ownership represents another method to reduce risk and so make the production systems more sustainable.

"Property ownership" whether it be land or in livestock, is not an undisputed right, but rather a claim that a person must always be ready to defend. If a person, for instance, is not able to protect the trees he has fenced (Ekwar), i.e., if no one is willing to support his interests, others may ignore his enclosure and collect fruits. Thus, in the same way as relationships to people are necessary to get access to land, they are also essential to protect use of land. Likewise, the line of confrontation in land disputes is not always between "insiders" and "outsiders" but can also be among closer family.

The people of Turkana have evolved well-managed and sound ecological strategies that enable them to utilize the vegetation on a sustainable basis through exploiting different economic niches (grazers, including cattle, sheep, and donkeys, and browsers, including camels and goats), as well as diversified food procurement. The Turkana silvopastoral system maximizes the use of the vegetation both in time and space through a transhuman system of wet and dry season grazing combined with the setting aside of specific dry season grazing reserves. Such a system of resource management is made more complex because of a variety of social controls concerned with sharing, flexibility, and mobility.

The Turkana system of rangeland is, broadly, livestock (particularly cattle) grazed in the lowlands after the rains to make use of the annual flush of grass, which may only last for a few months and the the stock will gradually move to the west and to the hills to make use of the dry season grazing areas. The hilly areas and the west are much wetter than the rest of the district. The Loima Range is probably the single most important dry-season grazing area for cattle in Turkana.

This herding movement reflects the way the Turkana divide their family and lives into two divisions, namely the abor and eogos divisions. The abor division occupies the hill areas and is comprised of young and mature stock together with the younger people while the eogos is the lowland “unit and is composed of old stock and older people. These relations are based on stock sharing, which is an important factor in strong continuing links to in-laws, relatives, and leaders. The maintenance of such ego-centered mutual support networks is based on stock sharing, which is an important factor in maintaining relations with in-laws and relatives, and the influence of the local Emuron or Ekadwaran (traditional prophet and sacrificer), all of which serve to spread risk. These are important factors in maintaining flexibility in coping with the different risks of disease, raiding, and drought.

Grazing, as well as being done in defined patterns, is carried out communally under what is called a cooperative grazing community or adakar. An adakar represents a fairly temporary (or more permanent if there is a security risk) cluster of homesteads that come together in the wet season. An adakar can vary greatly in size (40 to 100 or more families) and is formed usually among families who know each other and have ties. Adakars facilitate herd security and herding cooperation, together with a strengthened social network.

Usually, the herding unit follows roughly the same annual movement, but it also retains a relationship with the people who control the area and may want or need to use an alternative route. Such relations are based on stock sharing. This stock sharing is an important factor in maintaining relations with in-laws, and relatives and the influence of the local emuron or ekadwaran (traditional prophet and sacrificer). These are important factors in maintaining flexibility in grazing to cope with the different risks of disease, raiding, and drought. The Turkana have two forms of traditional reserved grazing areas. One, “epaka,” was introduced in the colonial era and is now well established in the grazing patterns, whereas the system of “amaire” reflects the traditional method of epaka. Now both terms are nearly synonymous. These systems of reserved grazing are usually large hill areas and grazed in times of drought.

It is this power over ownership of water and fodder that is central to pastoralism In Turkana. This is particularly critical in the dry plains areas and the herders depend, in the dry season, on the pods of the Acacia stands along the major water courses to provide fodder for their animals.

Because of the instability of the environment, such grazing communities cannot be permanent social groups. They have to have the organizational flexibility to react to climatic, vegetation, and disease criteria. Thus in the dry seasons such adakars will tend to break up as each group follows its own dry season grazing pattern.

The social organization of the household is a major determining factor for a functioning management system. Households organize labor and are the focus of the decision-making process, distribution of authority, property rights, and obligations among members. However, the survival strategy of a farmer is not restricted to the household level only but also to the supra-household level. Forest management systems at the communal (supra-household) level were found to be rather passive. They consisted mainly of sets of recognized use rights.

The trees and other woody species are recognized by the people as being especially important since they can survive and produce even through the long dry seasons. Ethnobotanical knowledge reflects the extent of their dependence on woody vegetation for such uses as dry timber for woodfuel and charcoal, building timber for houses, fencing, and thatching, food for livestock, particularly in the dry season, wild fruits and foods for people, veterinary medicines for a variety of livestock diseases, human medicines for a variety of diseases, making of household utensils, amenity for shade to act as a meeting place, and a variety of cultural activities, water purification, and ceremonials.

Turakan knowledge of their flora is almost entirely related to the plant values for their livestock and for people in terms of food, medicine, and materials. Researchers in the 1980s found that out of 307 plant species, 61 (20%) were used for food and 118 (39%) were used for medicine.9 Turkana knowledge is particularly well developed in the area of animal fodder where they can recognize species that will promote milk production, meat, dry- and wet-season fodder, and fodder for the different stock species and ages.

Trees are used on a sustained conserved basis for a variety of uses, including fodder and food, medicines, building materials, fuel, fencing materials, and household implements as well as acting as central meeting points for the elders and providing shade. During the dry season some trees will be pollarded for their browse, like the desert date and Garas, and pods will be harvested for livestock feed from other trees, like the Acacia. The only woody species that are cut back are the less useful bush species, primarily the bush acacias, which are used for fencing the homestead and livestock corrals. This cutting back of such woody species often serves to encourage a better ground cover of perennial grass in the following growing season. By keeping a full canopy over the grasslands, the temperatures on the soil can stay up to 20 degrees cooler, increasing the grass’s ability to grow and producing more fodder for livestock, despite making up less of the ground cover.

This importance of the woody vegetation is verified by the ecosystems’ resilience:

23% of the District woody vegetation is virtually confined to riparian strips. These areas coincide with the driest eastern parts of Turkana and dry season grass cover was found to fall consistently along a gradient of increasing importance in the riparian component. Despite the acute shortage of grass, areas of exclusively riparian woody vegetation supported over 30% of all livestock in the District during the dry season, underlining their extreme importance as a dry season forage resource.

Like most of Africa, colonization played a big role in destroying these systems of land management, but interestingly enough this region of Kenya has been less impacted by colonists than other parts of Africa. Despite this, intensive work was implemented to make the land more arable, which destabilized their complex land management systems. Things like irrigation were extensively implemented and created various problems in the communities, but active work is going into returning some of these traditional practices. Still, merging these two worlds has been a challenge.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 15-page chapter, of (so far) an 1145-page book with 778 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #31, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Wright, David. (2011). Holocene occupation of the Mount Porr strand plain in southern Lake Turkana, Kenya. Nyame Akuma. 76. 47-62.

Liu, T., Lepre, C. J., Hemming, S. R., & Broecker, W. S. (2021). Rock varnish record of the African humid period in the Lake Turkana Basin of East Africa. The Holocene, 31(8), 1239–1249. https://doi.org/10.1177/09596836211011655

Marshall, Fiona & STEWART, KATHYLIN & BARTHELME, JOHN. (1984). Early domestic stock at Dongodien in Northern Kenya. Azania:archaeological Research in Africa. 19. 120-127. 10.1080/00672708409511332.

Goldstein, S. T., Shipton, C., Miller, J. M., Ndiema, E., Boivin, N., & Petraglia, M. (2022). Hunter-gatherer technological organization and responses to holocene climate change in coastal, lakeshore, and grassland ecologies of Eastern Africa. Quaternary Science Reviews, 280, 107390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107390

Morgan, W. T. (1981). Ethnobotany of the Turkana: Use of plants by a pastoral people and their livestock in Kenya. Economic Botany, 35(1), 96–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02859220

Oba, G., Stenseth, N. C., & Weladji, R. B. (2002). Impacts of shifting agriculture on a floodplain woodland regeneration in dryland, Kenya. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 90(2), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8809(01)00355-3

Okoti, M., Ng’ethe, J. C., Ekaya, W. N., & Mbuvi, D. M. (2004). Land use, ecology, and socio-economic changes in a pastoral production system. Journal of Human Ecology, 16(2), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2004.11905720

Barrow, E. G. (1990). Usufruct rights to trees: The role ofekwar in dryland central turkana, Kenya. Human Ecology, 18(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00889180

Kajembe, G. C. (1993). Indigenous management systems as a basis for community forestry in Tanzania: A case study of dodoma urban and Lushoto districts. This particular book was a huge source for much of this piece.

I really appreciate these focused descriptions!