Liberty Hyde Bailey is likely a name many folks are familiar with, but the depth of knowledge of his significance remains fairly thin. A cursory search online highlights various facets of his career— his work in pomology, his defense of rural living and communities, and his importance in the re-discovery of Mendel’s work on recessive traits. While all of these are important, they simply scratch the surface of what Bailey has contributed to numerous fields of science and philosophy and miss the larger vision that motivated Bailey.

Bailey grew up amid apple orchards in rural Michigan, the son of a Vermont farmer named Liberty Hyde Bailey and a southern woman named Sarah Harrison who were among the first frontier people to take up residence along Lake Michigan, near South Haven. His father had traveled under the expectation that South Haven would be a thriving town but instead found wilderness. While we don’t know the specifics he likely became acquainted with the Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Miami who had inhabited the region for more than a century.1 Two years later his father purchased another piece of land in Arlington township where Liberty Hyde Bailey Jr.’s two older brothers would be born, and he later returned with his small family to his original piece of land in South Haven where a cabin was built, and where Liberty Hyde Bailey Jr. would be born on March 15, 1858.

In the senior’s absence, indigenous people had returned to the lands he had purchased, whom he had once known and rekindled a friendship with. He would fish and hunt and share his lands with these folks, and began to build an apple orchard that would become one of the most noted in Michigan’s pomological history— with trees that were documented as still standing in the 1960s. Unfortunately, during this same period, scarlet fever had entered their family home and laid to rest Liberty’s oldest brother Dana, and his mother followed only a year and a half later in 1862, leaving the four-and-a-half-year-old Liberty with only a few memories of his mother, including her love of her garden. He continued to maintain the garden after her death and kept the same plants growing in it as long as he remained on the farm, even taking roots from the garden when he moved away.

His father continued to bury himself in his work and quickly remarried Maria Bridges in 1863. It was in these orchards where Liberty Jr. would begin his time working; at ten he had begun to top-graft trees and was following his father around the orchards. He became so proficient at grafting, that certain varieties of apple could be only found in the Bailey orchard, such as the Surprise Apple. Not yet a teenager, he was hired by local farmers to graft apples in their fields.

Bailey spent as much of his childhood as possible often alone in the woods. He would bring home captured animals, to the dismay of his stepmother, and his school teachers would try to help him understand the world around them— as best as they could. In the world Liberty grew up in, school was ungraded and largely self-directed. However, his father supported his interests, and despite his firm religious values, supported Liberty in reading a rare copy of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species that had managed to find its way to their small town. At fourteen, he found his first botany book, and his interests in the woods and gardening had all come together and his first herbarium was born. At fifteen, he was giving talks on grafting before apple farmers, considered a master in his field. At nineteen, Bailey left the small town, guided by the support of his father and stepmother, to attend the agricultural college in Lansing.

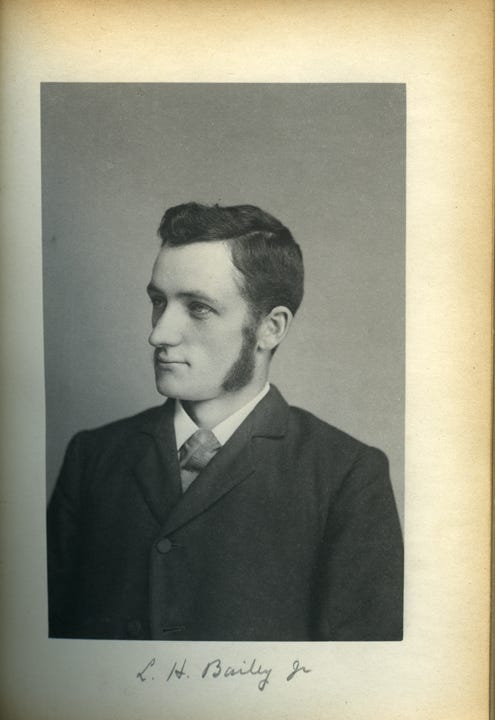

Michigan’s Agricultural College was funded in part by the Morrill Act, which is one of the key figures in the development of the agricultural education system that expands into land colleges and extension schools today. We chatted about this a bit when discussing Efraím Hérnandez, but by the time Bailey attended school, the program had been in place and Michigan Agricultural College had tens of thousands of acres available for experimental agricultural projects. It was here, at his entrance examination, that he would meet his future wife Annette Smith. He attended school for three years before he experienced a bout of health problems, leaving him unable to walk for long periods without passing out. After a surgery of some kind, he returned to finish school in 1882. During his senior year, Bailey organized with other students to establish one of the first college quarterly journals in agriculture— in which he was the first editor-in-chief. But before finishing school, the “young genius” as he was described by his professors, wrote an editorial in The College Speculum that:

“The farmer of today knows nothing of the drudgery which characterized his profession a hundred years ago. This change has been wrought by no other force than the systematic and scientific efforts of educated leaders… The principles of science that underlie their labors will be applied vigorously… If every county in the north had within its limits one business-like graduate of some scientific institution, and he a farmer, there would be just so many centers of power for the elevation of agricultural industry.”

And Bailey would be one of those graduates.

Bailey’s Post-College Life

After graduating, Bailey returned home, assuming a role on the farm and considering his next steps. He took a role writing for the Springfield Monitor, and just as he was promoted to city editor, he received a letter from Dr. William James Beal, one of his former professors, who had recently transferred to Harvard and was looking for Bailey to join him in his botanical work with Asa Gray, considered the most important botanist of the 19th century. Bailey quickly accepted, and found residence in Cambridge only a few months later, in 1883. Having moved across the country and away from those he cared about, he wrote to James M. Smith, asking for his daughter’s hand in marriage. Annette Smith & Liberty Hyde Bailey were married on June 6, 1883.

Within a few short years, Bailey was promoted to Assistant Curator of the Harvard University Herbarium and oversaw the students & garden herbariums at Harvard. When the Gray Herbarium work was concluded, Bailey continued to work in Boston, which was considered to be the leading American horticultural center of the time, including working with Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, established only a decade earlier in 1872. During this time, Bailey continued to build a close relationship with Asa Gray, who pushed Bailey to consider the future of botany and horticulture. What was the point of botany if it wasn’t explored for horticulture?

Bailey would get his chance to answer that question a few years later when he was offered the position of superintendent of the horticultural department at Michigan State Agricultural College in 1885, at a mere 27 years old. It was here that Bailey would propose a “new” horticulture.

Michigan Agricultural College

Bailey was the face of the momentous change taking place in the fields of botany, horticulture, and agriculture. On the shoulders of the work of folks like Darwin, Gray, and many others, the ideas of evolution and the concepts of plants being part of a much larger and more complex system reflected his new approach to these fields. There were new, far-reaching problems of plant origins, changes, and development to address while also considering the more immediate problems of understanding how new management methods through chemicals were going to change both plants and the pests and pathogens they were attempting to control. In short, the fields of botany and horticulture were fundamentally reshaped over a few short decades, and the reigns were being handed to men like Bailey to begin the process of navigating these new rules.

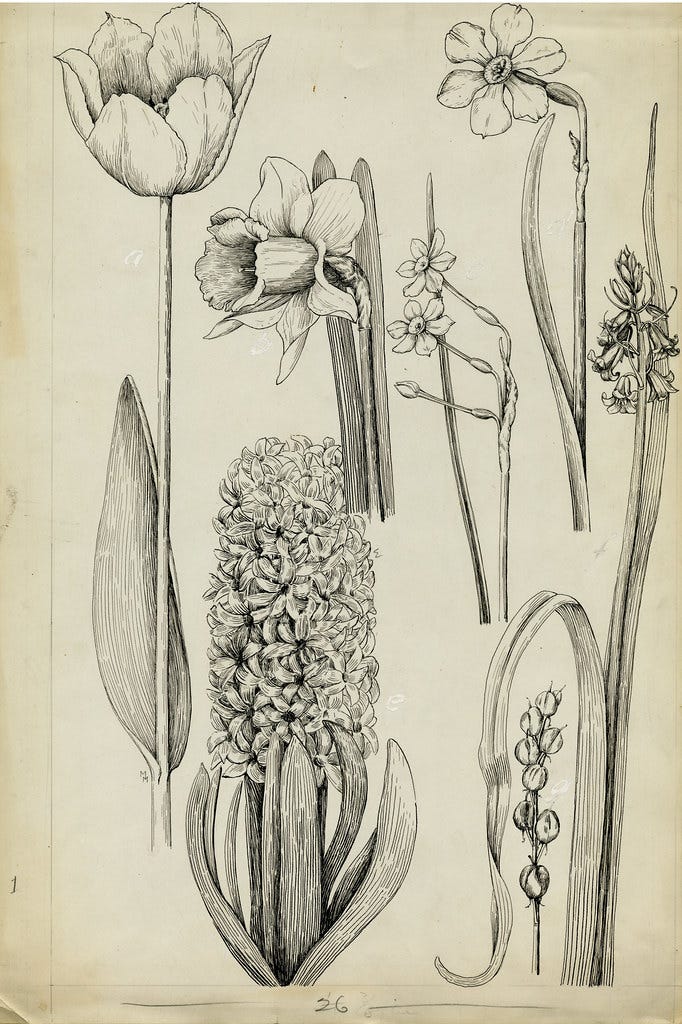

His first year was spent restoring the orchards and installing new experimental gardens, including vegetable, fruiting, and grape vineyards. His goal was to begin the process of documenting these plants across their lifespan— from average germination rates to periods of fastest growth to the characteristics of leaves and flowers. Bailey wanted to create an exact record of the whole visible biography of our cultivated plants in a way that had never been done before. While botany had been given labs to do tests and analysis of plants for cataloging, horticultural materials were not given similar treatment— and Bailey was filling this void.

However strict Bailey was in driving economics into horticulture, he was equally motivated not in simply improving the farming business which rural life depended on in small towns like where he had grown up. He wanted to improve rural living itself, both through economics and aesthetics. To do this, he was drawn to the beauty in the native plants Michigan had to offer. “Many wild plants, especially some of the shrubs,” he wrote, “are worthy of cultivation in the dooryard. Some of our attractive swamp shrubs thrive on any garden soil. One never appreciates the beauty of many common plants until he sees well-grown specimens in the garden.”

Bailey’s programs grew. Experimental fruit plots improved, the gardens expanded into experimental grains, and new greenhouses were erected for the expansion of tropical and sub-tropical plants. Concurrently, Bailey believed it was important to preserve natural beauty, and that wild, native plants could be brought into cultivation for landscaping— for example, he brought wild roses to Michigan’s landscape to highlight the potential of native plants.2

Bailey’s fixation on native plants wasn’t just on their beauty, but their potential to be used as food crops. He advocated for breeding work for wild gooseberry, the cultivars Wild Goose and Miner, which were native Chickasaw plums, sand cherries, wild crabapples, pecans, and all other native nuts, pointing out that:

There are no less than twenty-five fruits, of various kinds, natives of Michigan, which present attractive problems to all lovers of botany and horticulture… The Horticultural Department desires to undertake the solution of a few of these problems. Our present method must be to plant the seeds of the finest wild fruits and await results. We desire the cooperation of the students and others in securing seeds of the largest, smoothest, and sweetest of all kinds of native fruits.

It was at this time that Bailey refined his idea of a “new horticulture”, as he outlined in a lecture titled “The Garden Fence”— in it, he advocates bringing science into the fields, and seeing experiments run by both scientific and practical men. This concept didn’t just apply to the research of science, but the distribution of it to the layman. Bailey firmly argued for better education for farmers and youth, working to put together materials that could be applied in rural schools to teach future farmers fundamentals about agricultural science and botany. Bailey argued that his goal wasn’t to make farmers think like him but rather to help future farmers see, investigate, and think for themselves.

If it isn’t clear already, Bailey was a champion of many of the fundamentals around agriculture and botany as we understand them today. He was also one of the first major proponents to write about and advocate for research around acclimatization; the idea that plants could learn to adapt to new climactic conditions. Bailey urged scientists in 1887 that “[w]e need to study our plants in the field rather than in the herbarium to acquaint ourselves with their entire history, and their habits.” This included studying plants in their native habitats as well. That domesticated plants could handle climates their wild counterparts could not speak to the potential through selective breeding, which at this time was poorly understood, but of course, Bailey was one of the leading figures in advocating for research around hybridization, as we will see, which until this time had been considered only for the lowly farmer.

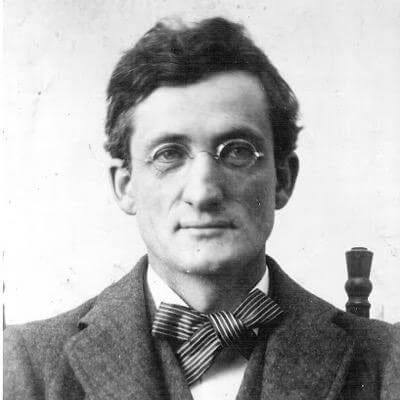

Despite his hands being involved in so many things, the following spring he took the position of Director at the agricultural experimental station at Cornell University. While the position wasn’t necessarily a promotion, the true reason for his acceptance was that Cornell intended to send Bailey to Europe to study their horticultural research and administration. Upon announcing his departure to Michigan Agricultural College, the president of the school responded “In that event you must go. You can do more for the advancement of M.A.C. than if you stay here at what we can do for you.” It was understood that the benefits for all of horticulture through Bailey’s overseas study far outweighed the importance of the college’s immediate needs.

His first responsibility at Cornell was to leave— and he did, starting in Ireland, where he had proposed that the term ‘sod crop’ be replaced with ‘cover crop’. His words were followed, as he had become America’s foremost expert on the Carex genus in between all of his other responsibilities as an administrator and academic. While overseas, he utilized cameras to take pictures of specimens and in this process developed the photographic procedure for documenting plants that would become the standard in botany. He traveled across Europe, connected with the world’s experts in a variety of species, and returned home excited to develop new research.

Returning to Cornell, he quickly pivoted his research into “electro-horticulture”, inspired by the extensive greenhouses seen across northern Europe. While greenhouses were used, he was interested in studying the impacts of electrical lighting on plant growth— an otherwise unexplored area of research. Being Bailey, his research was never focused on one area. He was also actively working on Cucurbita hybridizing, and his failures to produce better crops provided the basis for our understanding today of hybridization and the work indigenous people had put towards domesticating pumpkins and gourds. Bailey worked tirelessly and continued his interests around domesticated ‘backyard’ crops, alongside his interests around also incorporating more native plants for ornamentals and his other various experiments.

In 1890, he wrote how he felt all of these disparate interests were coalescing into one narrative, writing that:

I have my plans of life work… firmly and fully set… a large work which as floated as a phantom before my mind for years is now assuming shape and I hope to see it done in a couple years. It is a work, a philosophical work, upon the variation of plants under culture. I am getting a number of minor works off my hands to leave me freer for this. Rule-Book is done and Annals is launched. I have mss for a companion to [the] weeks. Two other small books are well under way and I shall get them off within a year if all goes well. Then I have the most interesting and extensive series of experiments on plant variation ever planned in this country. These demand constant attention. Besides I am making a comprehensive study [and herbarium] of cultivated plants.

Bailey’s horticultural grounds, including several greenhouses, had taken over fifteen acres at Cornell. These included fruit and nut trees, fruit bushes, wild fruits that had yet to be improved including Juneberries and American plums, native roses, and of course his annual vegetable crops. The collection was meant to expand to include every domesticated plant across the globe— today this collection is known as the Bailey Hortorium, which has over 880,000 specimens.

Bailey’s interest in publishing and making information accessible drove his interest to develop a singular publisher responsible for distributing new research to farmers of all types across the country, and this led to his involvement with the development of the Garden Publishing Company. Bailey’s concept of a “Rural Library… a series of monthly issues of popular pamphlets on scientific and practical topics in agriculture & horticulture” became a common theme in what would become the permanent agricultural movement, whose torch was picked up with the Friends of the Land, developed by Russell Lord. Functionally, what Bailey aimed to publish was a series of manuals— for example, The Pruning-Book (1898), The Nursery-Book (1891), and The Forcing-Book (1897) all outlined the fundamentals of their specialization based on the most recent research with extensive diagrams for farmers to follow. In his annual publication, the Annals of Horticulture, Bailey focused the 1891 issue on native North American plants and their horticultural varieties, the first attempt at cataloging native plants and their uses in history.

Now his interest in cataloging domesticated varieties wasn’t because of an interest in saving them— in many ways, quite the opposite. He understood and advocated that varieties would disappear as they became ill-adapted to various conditions, but they are also “supplanted by better varieties, or those which more completely fill the present demands or fashions. The disappearances are, therefore, so many mile-stones to our progress”. To Bailey, the fluidity of change itself was a reminder and focus of his work— that attempts to force plants to remain static would inevitably be their demise. However, he urged that this framework for crops be focused on the capacity of native plants to meet our needs; that native plants showed better resilience and often pointed to how cultivation of many plants failed until they were hybridized with natives.

The 1890s was a decade in which Bailey single-handedly made horticulture in the image he envisioned. Speaking to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he advocated for physiological studies of the plants which fruits came from, which is now the basis for the botanical drawings plastered in every upper-class urbanite home. In 1893 he proposed that certain fruit tree varieties may not be self-fertile— and in this process advocated for more inter-variety cropping and that attention would have to be paid to flowering times for different varieties to ensure cross-pollination. All of these assessments were on the mark and would later be proven in research circles.

He devoted himself to everything wholly; to making academia intelligible, college extension work for farmers, the teaching of rural folk about the sciences and the city folk about native plants, and to work on the books and studies he was always engrossing himself with. And, of course, his interest in growing the horticultural program at Cornell. In 1887, less than 50 students were enrolled. By 1892, over 100 had signed up, and Bailey demanded that the program continue to grow. That same year, Bailey had undergone a serious illness that was fixed by Dr. Robert T. Morris, the same Robert T. Morris who would later write the book “Nut Growing” in 1921 and advocate for the tree crop movement decades later.

The weight of Bailey’s words at this point, even still a young man, cannot be overstated. When he wrote a public recommendation to require to control of contagious diseases for plants, the state of New York enacted a yellows and black-knot prevention law that same year in 1893.

In 1894, the Nixon bill was passed and provided the foundation for large-scale horticultural extension work, and of course, Bailey was at the center of it. Research, guided by Bailey, went across the board, from poplars to cabbage and everything in between. Short courses were designed for the winter months when farmers were slow to give them access to new research and techniques that they would otherwise not have time for. Cornell’s extension school would be a model for the rest of the country.

Part of this funding went towards developing forestry resources, and the first university with a forestry program was Cornell. The program stood as a separate college for forestry, which Bailey disagreed with, as he had begun to find an interest in the potential for tree crops and the concept of permanent agriculture, which we will touch on later.

Lastly, funding from this bill was to inspire younger generations to have an interest in farming, as rural folks had been moving out of communities due to the poor conditions and little money in the farming industry. Bailey, alongside Ms. Anna Botsford Comstock, traveled across New York state to share basic courses for elementary school kids around the fundamentals of plants. The program was so successful, that four full-time teachers were put on staff at Cornell to travel the state, working with elementary school teachers to develop a curriculum on the basics of plant science. Anna Comstock would later be recognized as one of the twelve greatest living women for her 800-page collection of leaflets made for this program.

The program’s success inspired an entire generation of what Bailey described as “nature-studiers” In 1897, Bailey described the purpose of the program to:

…take the the things at hand and endeavors to understand them, without reference to the systematic order or relationships of the objects. It is wholly informal and unsystematic, the same as the object are which one sees… It simply trains the eye and the mind to see and to comprehend the common things in life; and the result is not directly the acquirement of science but the establishment of a living sympathy with everything that is.

Quickly, the program expanded and included both boys and girls. Alongside the growth of this program and its replication across the nation, the food system in America began to shift as these children brought home new knowledge to their families. Farmers engaged with the extension programs for adults while their kids enrolled in the nature-study programs led by Bailey and Comstock. Over the decade, industries that had been faltering for decades began to show new interest— fruit trees and annual vegetable farms began to expand and show better profits as the new techniques and technologies in the industry were implemented. Over 50,000 subscribers received these newsletters by 1900.

Again, Bailey focused his efforts on education, and announced in 1896 that he would be releasing a series of bulletins with the fundamental goal that they would “be used as texts in horticultural societies, granges, and farmers’ clubs”. These readers weren’t to have any new information, but rather to parlay information to farmers, and the bulletins would be drawing from and guiding its readers to read F.H. King’s book “The Soil”, which would be the first of what he called the Rural Science Series. King’s work was so important to Bailey that not only was it used as the first in this series, but he even wrote the preface to King’s book.

These bulletins would go on to stretch over 7800 pages before they were done. They expanded to include reading courses on farming not just for youth and farmers but their wives as well, with nearly 6,000 women enrolled at its peak. Bailey was clear that the goal of his educational programs wasn’t necessarily to teach technical knowledge but rather to “awaken the pupil’s interest in the things with which he lives.”

During this same period, Bailey began to speak publically about the concept of plant plasticity before the terminology existed— he described that plants followed ‘tendencies’ based on necessity and that the development of the plant’s attributes was a mix of hereditary traits as well as a reaction to environmental factors.

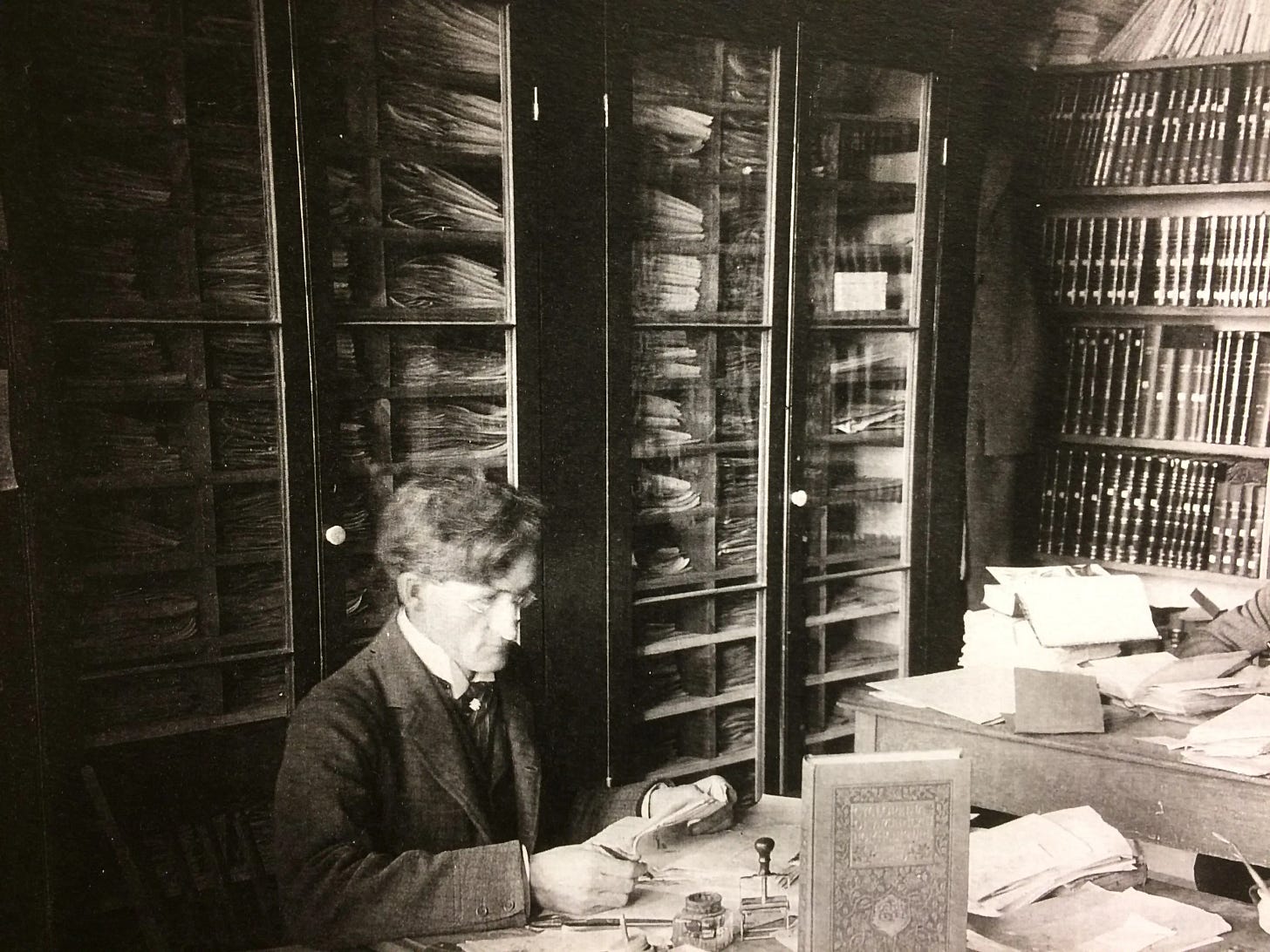

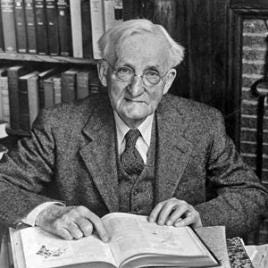

Applying this concept to how plants were organized botanically made all previous attempts to create a system for plant organizing unnecessarily convoluted and inaccessible. Bailey had been aware of this issue since his years as a college student, and over many years had been working on the Cyclopedia of American Horticulture, which would span four large volumes and revolutionize horticulture and the nomenclature used in botany around cultivated plants. Being the indefatigable Bailey, after its release in 1901, he immediately began to work on the Cyclopedia of American Agriculture which was released 8 years later.

Meanwhile, he continued to push out research papers while digging through research overseas. It was in 1892 that Bailey released a paper on cross-breeding and hybridizing which cited Gregor Mendel’s now famous “Plant Hybrids”, which had been written nearly 30 years prior and had remained largely buried. Through the work of Bailey and others, respect and research were beginning to develop around hybridization, and the federal government’s interest in improving crop yields through hybridization accelerated this trajectory.

In 1903, Bailey was offered the position of Dean of the College of Agriculture and director of the Experiment Station at Cornell, a position he was hesitant to take as it would pull him away from his research. His first focus was on raising money for new buildings and developing new programs around livestock— primarily chickens and cows. Due to his name recognition, Bailey began developing funding from private sources while also expanding experimental sites— there were nearly 300 experiments distributed over 44 counties in his first year alone. Bailey remained Dean for a decade, and the program exploded; within that time, the faculty grew from nine to one-hundred-four, the student population grew from 252 to 2,305, and the course offerings expanded from twenty-five to two hundred and twenty-four.

During this same time, he single-handedly strong-armed politicians into funding a state college of agriculture at Cornell in 1904, appropriating $250,000 for the development of new buildings. When Bailey had asked for support from the legislature, the representatives asked him what he was drinking to even ask for such a request. Little did they understand the power behind Bailey and his vision. In the words of Charles R. Barnes, “Professor Bailey is a living disproof of the doctrine that overproductiveness is at the expense of the quality of the fruit.”

In reality, Bailey simply attempted to follow the world he felt we needed. In his words:

Some man some day will see the opportunity and seize it. The result of his work will be simply a new way of thinking, but it will eventuate into a new political and social economy. When his statue is finally cast in bronze, he will not be placed on a prancing steed nor surrounded by any symbols of carnage or of war. He will be a plain man in citizen’s clothes, but he will stand on the ground and his face will be towards the daylight.

In 1906, the Adams Act was passed and designed to back the preliminary studies in genetics and specifically hybridization. The money funding research around hybridization, as well as soil science, that Bailey had been advocating for when no one else believed in its potential provided the basis for the massive leap forward in collegiate education around plant pathology, including Bailey’s demand to create a new chair of plant pathology at Cornell, the first in the nation.

And yet, Bailey’s chief concern was not of scientific solutions to pressing agricultural or botanical questions, but rather that “[t]he greatest problems of American agriculture… [are] the relations of the industry to economic and social life in general”. His politics and beliefs in community rang through his work and advocacy, preaching the important work of the Grange and their dedication to coeducational meetings. The opportunity to apply his beliefs and to leverage his cultural power was given new life on October 1, 1908, when he was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt to serve as the chairman of a national commission to study and make recommendations for legislation to improve country life by, to use the President’s terminology, “better business and better living.”

Bailey would lead a team of folks picked by himself and the president to find solutions to the nation’s rural issues. After traveling the nation and collecting data from over 600,000 people, the results were published in the Report of the Commission on Country Life in 1911. The weight of the book hung over agriculture and rural politics for decades— it advocated for a nationwide agricultural extension project, and in 1914, the Smith-Lever Extension Act was passed to provide resources for cooperative agricultural extension work between colleges and the USDA— a bill which Bailey had been consulted on repeatedly.

However, Bailey’s advocacy wasn’t simply about the farmer’s farm; he advocated for the spread of cooperative societies— semi-religious organizations, social centers, and more were necessary to maintain the quality of life and community necessary for rural areas to maintain their identity and sense of place. The fundamental problem was maintaining rural civilization, and to do this, new agriculture and new rural life were necessary, and the only ways to do this were through education and propaganda. Throughout his tenure as a voice in agricultural education, he set out to reform high school agricultural education, including the development of the agricultural high school Russell Lord would graduate from only a few years later in 1911.

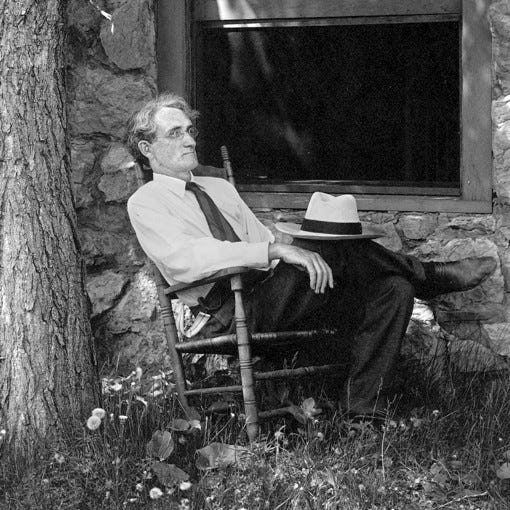

In 1913, Bailey stepped down as Dean of the New York State College of Agriculture. He had promised to be Dean for a decade, and he had honored it. The year after he retired, the students of the college memorialized Bailey as “without a doubt… the most useful man that American agriculture ever produced.” He dedicated his retirement to writing and studying plants “in earnest”. Two years after retirement, he published The Holy Earth, a naturalist philosophy outlining his belief of the relation between man and the Earth.

We come out of the earth and we have a right to use the materials, and there is no danger of crass materialism if we recognize the original materials as divine and if we understand our proper relation to the creation, for then will gross selfishness in the use of them be removed… We shall conceive of the earth, which is the common habitation, as inviolable. One does not act rightly toward one’s fellows if one does not know how to act rightly toward the earth.

The earth is holy… We are here, part in the creation. We cannot escape. We are under obligation to take part and to do our best, living with each other and with all the creatures.3

Fundamentally, Bailey urged for simplicity and deeper rooting of our lives in the soil and its products. In his older age, he often wrote about a slower way of living, a direct contrast to the accelerating process of science and development that marked the early twentieth century.

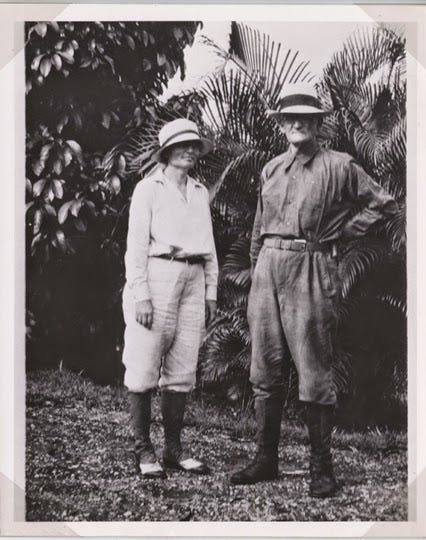

Bailey used his time to travel as well, and only five years after F.H. King published Farmers of Forty Centuries, Bailey left for China, returning in 1917 after three years overseas and a lifetime of stories beyond the scope of this work. With his return came a flurry of new writing, including the piece What is Democracy? in which he criticizes the recently deceased King’s position about the “permanent agriculture” of China, which he argues has become static and with “no prospect of advancement and progress for the race as a whole, and no real democracy”.

He would spend the next few years studying the plants he had returned with from Asia and writing about the need for better systemization of plant taxonomy. Incapable of staying in one place, he was off to Caracas and Trinidad immediately after, returning home with enough plant specimens, in his words “to keep us busy for the next two or three years. We are now sorting our material into piles and the work ahead of us looks very heavy.” So much for retirement.

Despite work for two or three years, the next year in 1922 he was off to Jamaica. While in Jamaica at their hotel, his wife asked him what type of palms lined the hotel. When Bailey replied that he didn’t know, she answered, “I thought you were a botanist?” and Bailey’s new obsession was born. He collected over 150 specimens, and the next year traveled to Brazil, where he brought home another 170 species of palms.

While he collected new species and cataloged everything for his hortorium (a term he coined), he continued to release updated editions of his books, putting out new books on evergreens, conifers, native blackberries, naturalist philosophy, and more. Every year he seemed to dive into a new species— his work read like a bibliography, and despite his age, he had not slowed down.

In 1935 he again went south— first to Cuba, then to Panama, in search of a rare palm—Raphia taedigera. Despite the downpours and risks of boa constrictors and disease, he and his wife went hip-deep into the waters of the Mohinja Swamp to find the tree at the age of 73. Returning home, another 150 species followed him, all of which led to his work defining palm tree systematics. It was during this time that he transferred the ownership of his hortorium to Cornell, where it would remain protected. Ethel, his daughter, would be the hortorium’s first curator.

The next year, he traveled to the West Indies and continued to release more books on gourds, larkspur, and Chrysanthemum through 1940, almost 80 years old. He continued to travel for plant exploration into 1946 when he took his last trip to the Amazon at 85 years old. He continued to research and study his own specimens well into his nineties and passed at a fully-lived age of 96 on Christmas Day in 1954.

Bailey’s spirit speaks to the need to find ways to capture the whole excitement of nature, to tie ourselves without fear to the remarkable depth, diversity, and fluidity of the natural world around us. Bailey lived multiple lives in the course of one chasing every excitement that drew him in from the landscape around him, and in doing so made the world a better place.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 23-page chapter, of (so far) a 964-page book with 621 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this episode, #197, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. Suppose you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content. In that case, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Rodgers, A. D. (1965). Liberty Hyde Bailey; A story of American plant sciences. Hafner Pub. Co.

18th Annual Report by the Sect. St. Hort. Soc. of Mich., 1888, p. 56

Bailey, L. H. (1980). The holy earth. New York State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Wonderful piece. I can’t wait for the book.