Pawpaw Mysteries: Unraveling North America's Tropical Hidden Gem

The fruit of little fame and much fanfare

The pawpaw, Asimina triloba, has recently gained attention in the perennial crops and foraging world over the past few years after generations of floundering off the radar. An oddity— seemingly out of place in North America— it has been called many things, from custard apple to poor man’s banana, although unrelated. Wild pawpaws are often kidney-shaped and are two to six inches long, growing in clusters. Not only is it one of the lesser-known fruits in North America, it’s also the largest and by a large margin. Here in New England, fruits ripen in early September (at least zone 7a), although in the deep south the season starts as early as July.

In the wild, they’re found alongside rivers, thriving in the deep soils of bottomland across the landscape east of the Mississippi as an understory tree beneath oaks, hickories, tulip poplars, and black walnuts. While it can cross pollinate, its best method of reproduction is through suckering— that is, sending up new sprouts or runners from its roots. The downside to this, from our perspective, is that these patches of pawpaws produce no fruit.

Now, the fruiting process for the pawpaw is unique— they’re not pollinated by bees but instead by carrion flies and beetles— they’re attracted to the pawpaws dark and smelly flowers that can be mistaken for decomposing animals. While the smell isn’t overpowering in your backyard, it’s enough to draw the necessary polinators across the landscape.

The history of pawpaws is quite unique— they seem out of place— and in a sense, they are. They’re the only members of Annonaceous in North America, and their closest relatives are soursop. Not surprising given their fruit shape and flavor profile. How they ended up here is still up for debate; the most likely theory is that a group of Annonaceous trees in the Rio Grande region likely included an ancient ancestor, and for whatever reason— most likely the last two ice ages— A. triloba was the only survivor to handle the harsh climate. During the last ice age, A. triloba was pushed south to Mexico and east to present-day Florida.

Well, that’s not entirely true. There are seven other Asimina species, six of which are only found in Florida & southern Georgia. The seventh is dwarf pawpaw (A. parviflora), which extends as far as Virginia. This species is unique, and the common pawpaw being the most unique. While the family Annonaceous contains over 2,000 species, Asimina is the only that can handle any frost at all, and triloba can handle temperatures as low as 20 degrees negative Fahrenheit.

Besides being a delicious fruit, the pawpaw has several other social and ecological benefits. The trees are the only host plant for the zebra swallowtail butterfly, who feed on the leaves during their caterpillar stage. Further, the pawpaw is a crucial understory tree for birds and provides necessary food for opossums, foxes, and more. The challenge, today, for the pawpaw is fragmented ecosystem and invasive species pressure. Pawpaw has show significantly higher rates of defoliation and death compared to other species. Evidence to this point suggests that pawpaw becomes a preferred species of native herbivores when other natives have been pushed out of an ecosystem, allowing invasive pressure to accelerate their growth into otherwise disturbed habitats.1

When colonists arrived in North America, pawpaws were of significant interest— in William Bartram’s Bartram’s Travels he discusses the pawpaw extensively. In Jesuit Relations of 1656-57, they write that “There are apples as large as a goose’s egg; the seed has been brought from the country of the Cats and looks like beans; the fruit is delicate and has a very sweet smell; the trunk is of the height and thickness of our dwarf trees; it thrives ins wampy spots and in good soil.”2 While today we consider the pawpaw to have been a fruit of the south and midwest, there has been documentation of pawpaw as far north as New York since colonists arrived.3

The question that also remains unanswered is how the pawpaw reached its northern distribution of the Great Lakes region. Researchers Craig Keener & Erica Kuhn’s posited that Iroquoian populations were responsible for pushing the trees as far north as Ontario.4 Others, such as James Murphy, have argued that the trees moved through dispersal by non-human omivorious animals, while the third perspective is based in both, and was first proposed by R. Neal Peterson.5

Keener & Kuhn’s proposition is centered on the descriptions provided by Jesuit Relations, that the pawpaw were only recently introduced around the 1654-1655 war, as they were associated with the war. If they existed before, they wouldn’t have such a strong correlation to a recent event. Still, to the south and west, there is clear evidence of human management of pawpaw; they were planted out of their natural habitat across the hunting trails between rivers in Kansas by the Kansa & Ponca bison hunters.6

Luys de Moscoso de Alvarado describes a pawpaw tree in Illinois country in the 1680s as so:

There are other trees as thick as one’s leg, which bend under a yellowish fruit of the shape and size of a medium-sized cucumber which the savages call asseminar. The French have given it an impertinent name. There are people who would not like it, but I find it very good. They have five or six nuclei inside which are as big as marsh beans, and about the same shape. I ate, one day, sixty of the, big and little. The fruit does not ripen till October, like the medlars.7

Ignoring the obvious language issue, what is worth noting is the use of the Algonquian word from which the species name Asimina is derived. The suffix -min- occurs in Algonquian languages in words when referring to the fruit or nut— such as in the words for blueberries, maize, and more. The Algonquian language was spoken into the region of modern New York, suggesting that the tree had a history in this region possibly prior to even reaching the midwest.

Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean the trees were brought this far north purposefully. We have fossils resembling A. triloba in New Jersey as far back as the Late Miocene, millions of years before humans walked across North America. Fossils were found in the Don Valley of Toronto’s excavation of a Pleistocene interglacial bed. The pawpaw species date back 34 million years in the fossil record.8 The ancient fruit were eaten by megafauna like ground sloths and the woolly mammoth, which could ingest large quantities of pawpaw and excrete the large seeds over long tracts.9

In reality, it was likely both indigenous people and megafauna responsible for the spread of the pawpaw. Peterson suggests that the humans saved some relict pawpaw stands from decline due to its aggressive homogenous shoots and from inbreeding through seed spreading.10 While we typically assign the value of pawpaw to its fruits, there have been reports of its use as a fiber and medicine plant; the bark was reported to use the inner bark for fishing nets by the Tuscarora. It is suggested by Peterson that stands were kept only if the fruit was good, putting selection pressure on fruit improvement over time.

Since the fruit stores poorly, it has historically been treated as a seasonal surplus. Evidence of seeds has been found in large, concentrated amounts, which suggests seasonal feasts when the fruit ripened. Some indigenous tribes created dried cakes of fruit pulp, both cooked and raw. This would be later used in stews and sauces, where in the case of the Iroquois, it was mixed into corn cakes, providing the high digestible niacin of the pawpaw with the low digestible niacin of the corn cakes.11 Pawpaws were often treated with lye or ash, similarly to how corn and acorns were nixtamalized and cooked. The Cherokee made rope and string from the inner bark. In the Mississippi Valley, indigenous tribes were observed growing pawpaw trees.12

However, the strongest evidence of human-mediated dispersal comes from genetic markers— that the documented ‘managed’ populations by indigenous communities shared rare alleles with wild populations at significantly greater distances than these rare alleles between wild populations alone.13 These rare genetics have been document to travel over 500 miles, speaking to their value as a food and materials source.

A Modern History

In modern times, the development of pawpaw as a viable crop has been split into three periods; the early 20th century, 1950-1985, and the present. During the early tree crops exploration during the permanent agriculture movement was focused on the discovery of superior wild selections, which lost steam alongside the permanent agriculture movement, moving towards World War 2.14

In 1916, the American Genetics Association, which had sponsored J. Russell Smith’s honey locust competitions, sponsored a contest for the best pawpaw. The contest was so successful that it discovered “better fruit than most horticulturalists thought possible”, and was responsible for discovering most of the known pawpaw varieties of the time, and received fruit from 75 trees. The winning tree came from Mrs. Ketter of Ironton, Ohio, and several of the trees were propagated (‘Ketter’, being the variety from the contest, and its parent, ‘Fairchild’, was also named). Unfortunately, the challenges of harvesting (the fruit doesn’t ripen easily if picked too soon) and storage (it has a very short shelf life) made it impossible to develop into a crop.

The first record of active variety development is documented in J.A. Little’s book Little’s treatise (1905). A small book, it identifies the first named pawpaw, ‘Uncle Tom’. This was an open-pollinated seed from superior wild fruits, and part of a “regularly laid out orchard” from select seed, consisting of 35 trees, on the property of Judge John V. Hadley in Danville, Indiana.15 Not far away in Farmingdale, Illinois, Bejamin Buckman collected twelve named pawpaw varieties— Buckman also was responsible for the ‘Farmingdale’ pear rootstock, and was an avid horticulturalist.

The prospects inspired George A. Zimmerman to undertake an 18-year project to breed pawpaws near Piketown, PA in 1923. The orchard would ultimately number over 60 named & unnamed varieties and likely included all of the known varieties of the time. Some trees in the collection were controlled crosses between better varieties but none of them were never named or released. Unfortunately, Zimmerman died in 1941 before his other crosses matured, and only three controlled crosses were protected— ‘Ketter’, ‘Buckman’, and ‘Taylor’. His widow donated these to the Blandy Experimental Farm in Boyce, Virginia.16

The Blandy Experimental Farm continued Zimmerman’s work, collecting new genetics and breeding, working with John Hershey, who sold unnamed crosses from their breeding work, and much of Hershey’s work was later incorporated into Ron Peterson’s breeding work. Other breeders continued to find new superior varieties and planted them out, such as Ernest J. Downing, who discovered ‘Middletown’ (1915) and ‘Madison-WLW’ (1938), which were propagated near New Madison, Ohio. Homer Jacobs, in 1934, planted seeds from an improved fruit, which he named ‘Sweet Alice’ (1945), which has been since lost. However, researchers have used RAPD markers and have traced Sweet Alice’s genetics in’SAA-Zimmerman-1’ & ‘SAA-Zimmerman-2’, supposedly.17 J.A. Allard, a USDA entomologist, collected clones from Virginia and bred them on his farm in the 40s and 50s. While none of these became named varieties, the genetics were worthwhile enough to be included in Peterson’s collection.

Into the 1950s, much of the interest of the pawpaw was driven by the Northern Nut Growers Assocation. It’s not surprising, since many advocates of the pawpaw’s potential were also NNGA members (Hershey, Smith, Zimmerman, Peterson, etc). Unfortunately, much of Zimmerman’s collection was lost after his death, and the collections at the Blandy Experimental Farm were largely lost after the retirement of Orland E. White, the director of the nursery (although much of the nursery is today part of the State Arboretum of Virginia). The long-term consequences of this cannot be overstated— in many ways, research started from scratch once again over the next 35 years.

In 1950, W.B. Ward discovered ‘Overleese’, from Rushville, Indiana, only 70 miles from J.A. Little’s managed orchard a few decades prior. Today, ‘Overleese’ has set the standard for fruit size and flavor. While it is assumed that ‘Overleese’ is wild genetic material, Peterson disagrees, as Indiana was a hotspot for breeding. Not only was Little based nearby, but others (such as Arthur W. Osborne, who provided Zimmerman with the ‘Osborne’) variety were very close by. ‘Osborne’ was collected only 15 miles away in Spiceland, and one of the runner-ups from the 1916 contest came from Julietta, only 30 miles away. This is a reminder of the importance of developing long-term plans for genetics; breeding work happens over multiple lifetimes, and without a plan to pass on this work, it becomes lost to history.

As the 70s and 80s rolled on, new varieties were named, such as Milo Gibson’s ‘Sunflower’ (1974), Corwin Davis’s ‘IXL’ (1976) and John Gordon’s collection of Pennsylvania Goldens ‘No. 1’, ‘No. 2’, ‘No. 3’, No. 4’ in 1986. Doug Campbell, at the northern range of the pawpaw in Niagara, introduced ‘NC-1’ in 1976, a seedling from ‘Davis’ that had been allegedly hand-pollinated with ‘Overleese’, according to John Gordon.

In 1981, Neal Peterson began a large-scale breeding program to develop improved pawpaw varieties at agricultural experiment stations in Queenstown & Keedysville, Maryland. 1483 accessions were open-pollinated seedlings, mostly coming from the collections of Blandy, Buckman, Hershey, and Zimmerman.18 By 1994, Peterson had selected 18 numbered selection and 10 named varieties .

During this time, in 1990, two more competitions were held for pawpaws, one by Brett Callaway at KSU, which generated more than 400 entries, most of which were new selections from the wild, with the winner coming from Salem, Indiana, the variety now known as ‘Wells’. The second competition was organized by Mark Blossom, with no varieties selected. The collection from the KSU competition led to a pawpaw research program at KSU, where much of the leading pawpaw research is being done today.

Today, pawpaw is somewhere in the middle stages of domestication. Breeders are working to create controlled crosses and hybrids of superior selections that can be released to the public, but no commercial orchards are yet bearing fruit. Peterson has developed a host of testing methods that should be considered for future research— he has pointed out that seed and fruit size see, to be controlled by the same genes, and a focus should be made on breeding fruit which show independence of seed size and fruit size. Fortunately, the largest cultivar also has only moderate seed size, which suggests that ‘Susquehanna’ might be a good starting point for breeding work. Based on the studies done on fruit production for processing (cited later), crossing these with P.A. Golden and Overleese would likely bear fruit with a wider range of seed size to fruit.

Pawpaw breeding is a long-term research requirement; 10 years per generation and 6 years for testing (fruit are not consistent year over year). Research is underfunded and offers the backyard grower an opportunity to put a few acres to good use. Much is still to be done, and the pawpaw community is active in attempting to improve the pawpaw selections available to us today.

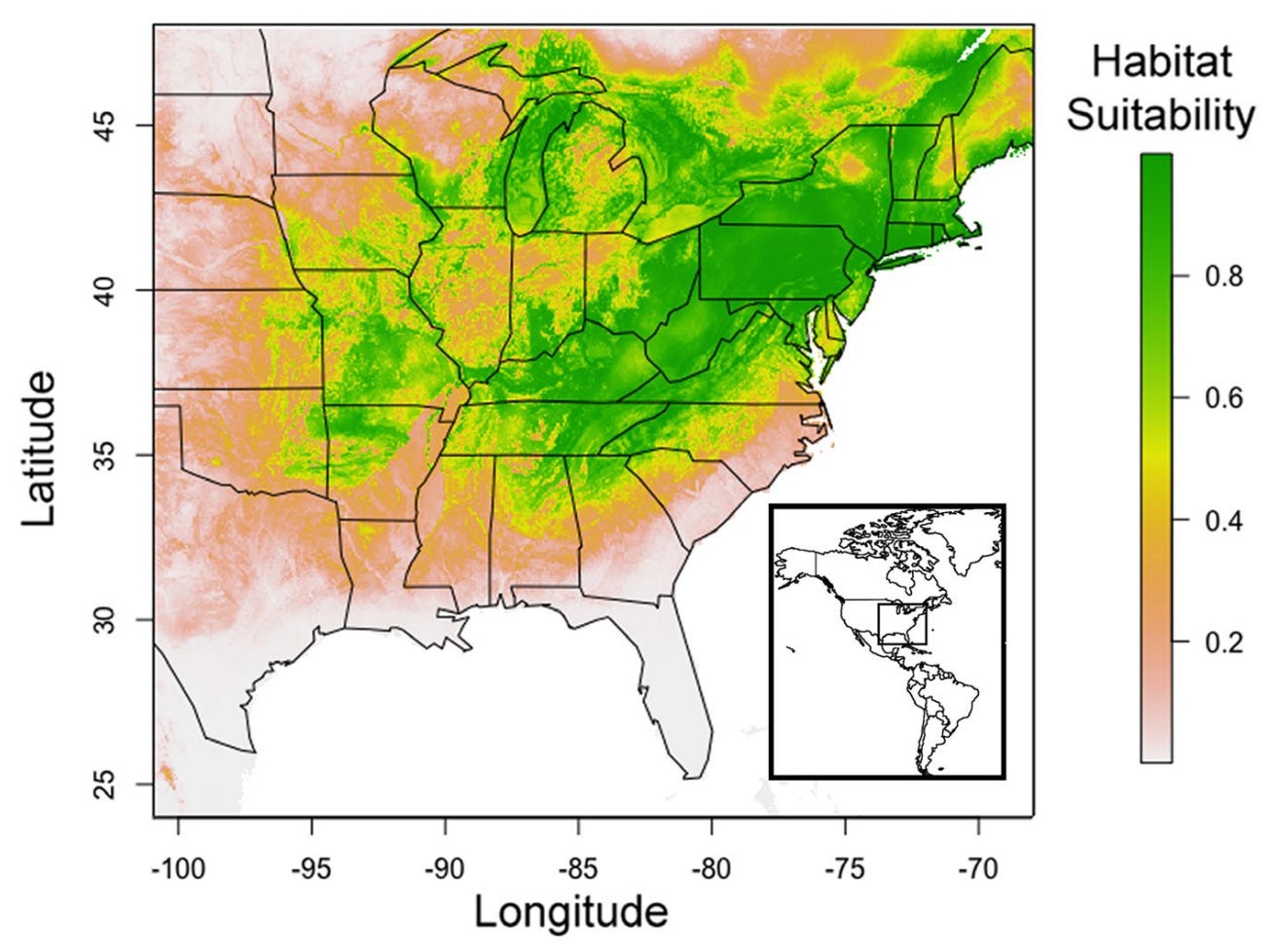

All of that said, the pawpaw may have a significant role to play in our future. By 2070, models suggest that the optimal pawpaw habitat will expand substantially northward. Genetic diversity indicates that there are two primarily population clusters straddling the Appalachian Mountains, offering two primary genetic resources for breeding and management.19

While we know that during the last glacial period, populations found refuge in Florida and Mexico (as we discussed before), we can see how these different clusters likely came from this history— cluster 2 migrated north and east, while cluster 1 migrated north and west from Florida. The mountains likely played as a barrier to dispersal, limiting the amount of genetic overlap as seen in the graphic above. Considering this within the context of the wild-selected varieties, it casually appears that cluster 2 produces better fruit and might be worth focusing more heavily when it comes to identifying new potential wild selections. Further, cluster 1 appears to show higher genetic diversity; this could be from less selection pressure in the past or it could be from more aggressive human selection pressure by the indigenous peoples near the Mississippi and further north, whom did extensive breeding work with other species (see the Adena & Hopewell here).

As Food

To this point, we’ve covered the limitations of pawpaws and why they’re not already across our store shelves. The rapid browning of the fruit is largely due to a neutral pH, which lacks the acidic qualities of shelf-stable fruits. However, researchers are looking to find ways to make the pawpaw part of our diets. One primary technique used to lengthen the shelf life of the pawpaw is through freezing. Of the various cultivars, ‘Susquehanna’ shows the most potential for freezing due to its fruit weight and pulp weight. Meanwhile, ‘Overleese’ may be best for juice production do to their higher liquid content.20 Today, most of the frozen and fresh whole fruit is sold to wholesalers who process it for beer, dairies for ice creams, and processors of jams.21

Another alternative to the conventional fruit usage is to utilize pawpaw flour. Samples of pawpaw flour mixed in with wheat flour showed that 10% pawpaw flour increased nutrients, especially vitamin A, while not meaningfully changing the flavor profile of biscuits.22 This also brings to light some of the more interesting data around pawpaw fruit. Much of the data around the nutritional profile of pawpaws is based on a 1982 study, in which its nutritional analysis was reported for the whole fruit, skin and pulp together, despite the fact the skin is not eaten. Despite its widespread citation, few have bothered to look at the fact these details are not correct. Fortunately, more recently, three studies were done, showing similar details about the nutritional profile of pawpaw. Using one-half cup as a serving size, pawpaw provides 25% of daily fiber, 6% potassium, and is comparable in many nutritional areas to banana and mango.23

Another narrative around pawpaw is regarding its safety to eat. Recent research has shown that the bioactive compounds in the tissues of the fruit show antitumour and anticancer properties, antioxidant activities, suppression of adipocyte proliferation, and anti-obesity activity, among others.24 In fact, the acetogenins responsible for the inhibition of cancer cells have been noted as worthy to research further for its therapeutic potential.25 It’s also these same compounds that can cause people to get sick from eating too much pawpaw, according to Dr. Jerry McLaughlin. While reactions to the fruit may happen, there is no conclusive evidence that I have seen that points to any long-term risks from eating reasonable amounts of fruit. According to another study out of the University of Louisville, those same cancer-fighting acetogens have been identified as toxic substances that inhibit “critical biological functions”.26

The other concern is regarding a possible link between Annona fruits and Parkinson’s disease, as there’s an abnormally frequent atypical form of Parkinson’s disease in Guadeloupe. While the figures are drastically higher than other regions, there hasn’t been any replicable studies to show that this has been consistent outside of this region, suggesting this may be a genetic condition unique to this region.27 The researchers simply suggest caution and more study, as the fruit contains a small amount of these acetogenins.

Within this context, the pawpaw is ripe for re-introduction into the American diet.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 15-page chapter, of (so far) a 1267-page book with 919 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #232 of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Mercader, Rodrigo & Paulson, Tyson & Engelken, Patrick & Appenfeller, Logan. (2020). Defoliation by a native herbivore, Omphalocera munroei, leads to patch size reduction of a native plant species, Asimina triloba, following small-scale removal of the invasive shrub, Amur honeysuckle, Lonicera maackii. Plant Ecology. 221. 10.1007/s11258-019-00998-x.

Greer, A. (2019). The Jesuit Relations: Natives and missionaries in Seventeenth-century North America. Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Wykoff, M. W. 1991. Black walnut on Iroquoian landscapes. Northeast Indian Quarterly 8:4-17.

Keener, C., & Kuhns, E. (1998). The impact of Iroquoian populations on the northern distribution of Pawpaws in the Northeast. North American Archaeologist, 18(4), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.2190/at0w-vedt-0e0p-w21v

Murphy, J. L. (2001). Papaws, Persimmons, and Possums: On the Natural Distribution of Pawpaws int he Northeast. North American Archaeologist, 22(2).

Wykoff, M. W. (2009). On the Natural Distribution of Pawpaw in the Northeast. The Nutshell.

Pease, T. C., & Werner, R. C. (1934). The French foundations, 1680-1693. Trustees of the Illinois State Historical Library.

Berry, E. W. (1916). The lower Eocene floras of Southeastern North America (Professional Paper 91). United States Geological Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0091/report.pdf

Guimarães, P. R., Jr., Galetti, M., & Jordano, P. (2008). Seed dispersal anachronisms: Rethinking the fruits extinct megafauna ate. PLOS One, 3(3), e1745. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001745

R. Neal Peterson, “Pawpaw (Asimina) in Genetic Resources of Temperate Fruit and Nut Crops 2”. Wageningen. The Netherlands. p. 570.

Samuel Cole Williams, ed., Adair’s History of the American Indians (New York: Promontory Press, 1986), 439.

Brode, J. (2020, May 1). Way down yonder in the paw-paw patch. Smithsonian Gardens. https://gardens.si.edu/learn/blog/way-down-yonder-in-the-paw-paw-patch/

Wyatt, G. E., Hamrick, J. L., & Trapnell, D. W. (2021). The role of anthropogenic dispersal in shaping the distribution and genetic composition of a widespread North American tree species. Ecology and Evolution, 11(16), 11515–11532. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7944

Peterson, R. N. (2003). Pawpaw variety development: A history and future prospects. HortTechnology, 13(3), 449–454. https://doi.org/10.21273/horttech.13.3.0449

Popenoe, W. (ed.). 1917. The best papaws. J Hered. 8:21-33.

Flory, Jr. W.S. 1958. Species and hybrids of ASimina in the northern Shenandoah Valley of V Virginia. N. Nut Growers Assn. Annu. Rpt. 49:73-75

Frost, Richard. (2022). Coupled analysis of Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) genetic markers and ancestry records. International Journal on Computational Science & Applications. 12. 1-8.

Peterson, R.N. A National Pawpaw Germplasm Collection. Pomona, N. Amer. Fruit Explorers Quart. 15:155-158.

Wyatt, G. E., Hamrick, J. L., & Trapnell, D. W. (2021a). Ecological niche modelling and phylogeography reveal range shifts of pawpaw, a North American understorey tree. Journal of Biogeography, 48(4), 974–989. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14054

Adainoo, B., Crowell, B., Thomas, A. L., Lin, C.-H., Cai, Z., Byers, P., Gold, M., & Krishnaswamy, K. (2022). Physical characterization of frozen fruits from eight cultivars of the North American Pawpaw (Asimina triloba). Frontiers in Nutrition, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.936192

Signorini, G. Pawpaw Marketing Updates. In Proceedings of the Ohio Pawpaw Conference, Columbus, OH, USA, 20 May 2023.

Maboh, J. & Awambeng, S. & Agbor, E. & Konsum, L. & Ezindu-Odoemelam, M.N. & Yakum, N.. (2024). Production of Biscuits from Wheat, Almond and Pawpaw Flour Blends and Investigating It’s Physicochemical and Texture Characteristics. Asian Food Science Journal. 23. 13-29. 10.9734/afsj/2024/v23i6717.

Brannan, R., & Powell, R. (2024). An exploration of the gastronomic potential of the North American pawpaw—a case study from the pawpaw cookoff at the Ohio Pawpaw Festival. Gastronomy, 2(2), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy2020007

Adainoo, Bezalel. (2024). North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba L.) fruit: A critical review of bioactive compounds and their bioactivities. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 149. 104530. 10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104530.

Nam, Jin-Sik & Park, Seo-Yeon & Lee, Hyo-Jeong & Lee, Seon-Ok & Jang, Hye Lim & Rhee, Young. (2018). Correlation Between Acetogenin Content and Antiproliferative Activity of Pawpaw ( Asimina triloba [L.] Dunal) Fruit Pulp Grown in Korea: Pawpaw acetogenin inhibits proliferation…. Journal of Food Science. 83. 10.1111/1750-3841.14144.

“Lisa F. Potts, Frederick A. Luzzio, Scott C. Smith, Michal Hetman, Pierre Champy, and Irene Litvan, “Annonacin in Asimina triloba Fruit: Implication for Neurotoxicity,” NeuroToxicology 33 (2012): 53–58.”

“D. Caparros-Lefebvre and A. Elbaz, “Possible Relation of Atypical Parkinsonism in the French West Indies with Consumption of Tropical Plants: A Case-Control Study, Caribbean Parkinsonism Study Group,” Lancet 354 (1999): 281–86.”

The fruit stand at our local farmers market used to bring paw paws for a couple of years. They stopped this year - couldn't make a profit. A couple years ago, we planted seeds from the paw paws and now have five growing on our property. They are very slow growing. Still tiny things, not mature enough to flower or fruit yet. Unfortunately, even a perfectly ripe paw paw makes me sick to my stomach! I looked up nixtamalization and found much on nixtamalizing maize but nothing about paw paws. Do you have a reference? What else might I do to make them digestible for me?