An American Energy Dream Fueled by Sunchokes: The Rise and Fall of the Jerusalem Artichoke Messiah

The Big Shart

The Jerusalem artichoke, also known as the sunchoke, has been a treasured crop of the permanent agriculture movement across the board for nearly a century. The primary reason it hasn’t become a staple crop in the American diet is largely due to the inulin within the root, which, without utilizing heat or fermentation, can cause severe gastric distress. While the potential of the sunchoke to be part of American cuisine can be debated today it’s just a vehicle for the real star of the show today, American Energy Farming Systems, or AEFS.

In history, the Jerusalem artichoke was enjoyed by indigenous people specifically in the northeastern part of North America. In 1605, French explorer Samuel de Champlain reported that the Indians at Cape Cod ate Jerusalem artichokes.1 Soon after North America was colonized, the plant was taken to France. There, known as the topinambour, it became a relatively popular food for humans and animals, especially pigs. Raw or cooked, the Jerusalem artichoke's tubers are delicious, and all parts of the plant can be eaten or fed to livestock. Anyone who grows them can tell you about how many calories they can produce with little to no effort, and in many parts of modern North America it’s considered a weed.

A Tale of Two Freds

Before we can jump into the organization, it’s really important to talk about the founders. Specifically, our good good friend, Fred Hendrickson, who is the central figure in this story, and comes to discover the Jerusalem Artichoke in the late 1970s as the American farm economy sagged and the nation was overcome by an energy crisis. Along with James Dwire, Hendrickson in 1981 cofounded American Energy Farming Systems (AEFS), a vision spearheaded by his dreams of a nation run by sunchoke.2

However, a half a century before Fred Hendrickson was under the Jerusalem artichoke spell, another Fred from the Midwest—Fred Johnson of Hastings, Nebraska—became infatuated with it. During the Great Depression, Johnson preached the Jerusalem artichoke as the savior of the prairie in crisis. He was, in the words of his biographer, "the first messiah of the Jerusalem artichoke."3

Now, Johnson was introduced to the Jerusalem artichoke by professors of agriculture at Iowa State University in the 1920’s who had great interest in the plant's promise. Johnson concluded that the Jerusalem artichoke was, in the words of his book, "the weed worth a million dollars." Johnson centered his life around the plant. He never left his house without carrying Jerusalem artichoke tubers in the pocket of his black suit. He would stop passersby along the street and take out a tuber or two to explain the great powers of the Jerusalem artichoke.4

Now, Johnson took up the Jerusalem artichoke prophecy in the early 1930s that "the extensive use of alcohol [fuel] is bound to take place within the next five years." In the 1920s, a growing alcohol fuel movement, called the power alcohol vision, took hold during the 1930s as farmers increasingly sought alternative crops to make their fields profitable, especially permanent crops, which we explored in depth here. This century centered national energy independence on the one hand while it immensely magnified the power of war on the other.

Johnson took the vision of alcohol fuel production to encapsulate his entire existence. Johnson underlined the Jerusalem artichoke's abundant production of levulose, a sugar that according to advocates to be "50 percent sweeter than sucrose or ordinary sugar and far better than sucrose for the human system."5 Like many things advocates of the Jerusalem Artichoke advocates claimed at the time, its claims were loosely substantiated and the fact had little to do with the main selling points they were also trying to make. Johnson was optimistically predicting that "a few months and a few thousand dollars, will guarantee the engineering success of the design of a commercial levulose plant."

Johnson eventually became a congressman in the 40s and used his public power to push a vision of a fart-filled future. The Second World War sparked an interest for national energy self-sufficiency and led a handful of scientists to again explore the Jerusalem artichoke. However, two energy crises of the 1970s—the first in 1973 and the second in 1979 —occurred before the plant was explored again.

It was during this second crisis in 1979 where Fred the second, Fred Hendrickson, rediscovered the Jerusalem artichoke. Fred Hendrickson, who as we’ll see, was singularly responsible for the creation of American Energy Farming Systems (AEFS), a small southwestern Minnesota company that spearheaded the sale of Jerusalem artichoke seed starting in 1981.

America’s Farms on the Brink

To fully understand the success of AEFS, we need to understand the context. The 1979 energy crisis was special; not only did it drive fuel prices to new heights, it caused the sharpest inflationary rise of the century. The question of energy dominated national concerns. Confidence in nuclear energy had been dashed by the accident at Three Mile Island. The price of oil, which shot up by 24 percent in the month of June alone, caused double-digit inflation in the United States. And like any time of uncertainty, snake oil salesmen came out of the woodwork with solutions, including ones you hear about today. So the future of national energy opened the platform to everyone who claimed to have answers. Not all of these people spoke apocalyptically; however, many did convey messages about the collapse of a world based on fossil fuels.

Many people, among whom numbered the founders and early farmers of AEFS, were attracted by energy crops and biomass conversion to methane or ethanol. Like their predecessors in the 1930s, they argued that new crops pointed the way to energy independence and the revitalization of American agriculture.

The point is, small and medium-scale farmers during this time in particular were squeezed, and the idea of novel new crops during this desperate time made bedfellows of all sorts of diverse groups that had interests in dramatic changes in U.S. energy policy. The onset of the farm crisis that swept agriculture in the 1980s supported the call for this change. High interest rates, low prices for grain, and shaky land values predicated the farm foreclosures of the middle 1980s.

The possibility of new and profitable crops for America's farms was a welcome message. It was especially appealing to highly leveraged and economically strained farmers, who found themselves borrowing at high interest rates while crop prices remained depressed.

What made the sunchoke have this moment of hope is the fact that a miracle cash crop did show up not too long before. The great majority of farmers were acquainted with the introduction of the soybean. Like many things, most of the work around soybeans happened in labs to develop the right plant for their conditions, and it seemed to just drop in their lap. They likely knew nothing of its early genetic development at agricultural stations at the end of the nineteenth century, its first milling in North Carolina and processing in Chicago during and after the First World War, and its further genetic, agronomic, processing, and marketing history in the 1920s and 1930s until it became the object of a single coordinated industry. It took 40 years of research, development and investment to create the soybean they grew, the soybean had saved them as it went from being a significant feed crop in the 1920s and 1930s to a major crop in the 1940s and 1950s to America's second most valuable crop in the 1960s, when it surpassed wheat, cotton, and hay.6

The time was ripe for the hopes of a new crop, and Fred Hendrickson and the founders of AEFS were among the boldest of those who envisioned a new, saving plant for America's fields. They preached to farm audiences, easily assembled during the energy and farm crises of the late 1970s and the early 1980s, that the Jerusalem artichoke— long known to farmers as a weed—offered the promise of wealth and independence. Exploiting the evangelical religious bent of rural communities, the founders of AEFS prophesied that the Jerusalem artichoke was "a Providential Plant," "a Biblical plant of promise," "the plant of renown" that, Ezekiel prophesied, "God would raise up to feed and save his people."

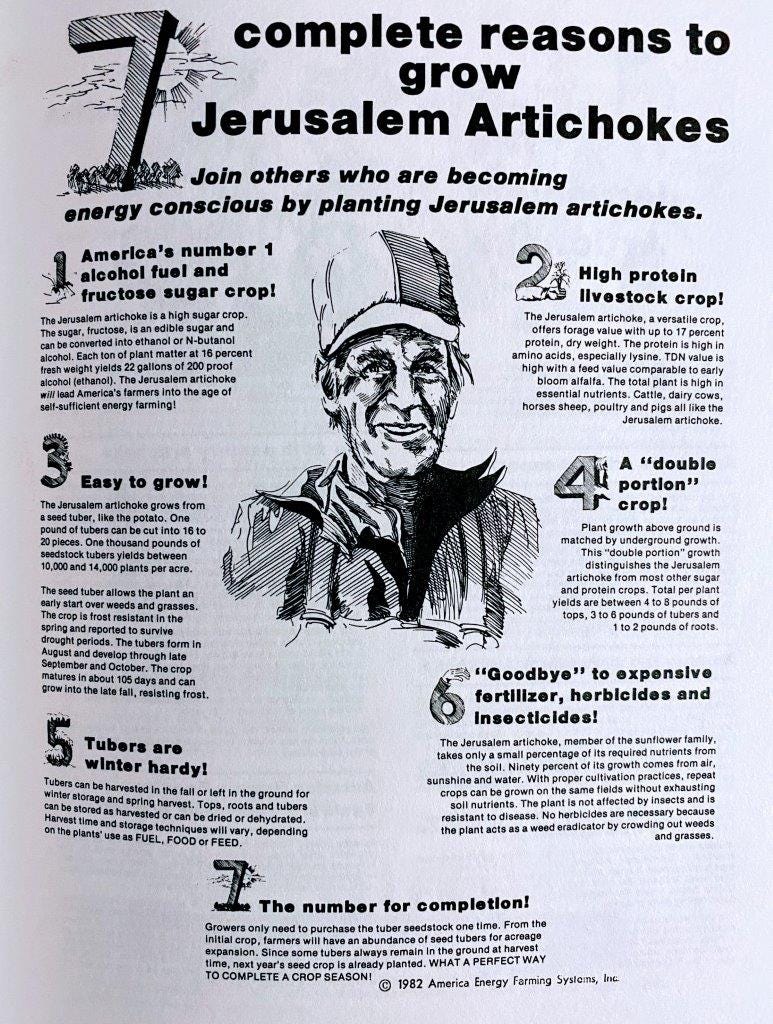

AEFS initially promoted the Jerusalem artichoke as a new and superior source of alcohol fuel. Its representatives boosted the distillation of alcohol fuel from the tubers of the Jerusalem artichoke as the road to farm prosperity and American independence from greedy cartels and foreign nations. It was religious nationalism wrapped in a plant.7

As oil and gasoline prices declined sharply, however, and difficult, even insurmountable, problems surrounded the distillation and the industrial conversion of Jerusalem artichokes into alcohol, AEFS quickly preached other virtues of the Jerusalem artichoke. AEFS advertisements increasingly drew attention to the promise of the Jerusalem artichoke as a source of sucrose and insulin, a substitute for starch and sugar, making it especially useful to diabetics. AEFS also suggested a possible use for Jerusalem artichokes as human food and animal feed.

Beyond this, AEFS sold something else: It sold hope—and desperate farmers and greedy speculators bought it.

While AEFS did not in the legal sense, at least as defined by Minnesota statutes, create a pyramid-sale scheme, since they sold something– the seeds– the driving mechanism of its sales was pyramid-like. And we’ll discuss how close it was to a pyramid scheme shortly.

The structure was something like this: their first-year growers (called three-year growers) intended to sell their seed to their second- and third-year growers, while second-year growers (their two-year growers) intended to sell their seed to third-years growers who would still enjoy the phenomenal advantage of getting in on the ground floor of a new American crop.

While Fred and the gang expected things to go well, their sales exceeded its founders' wildest dreams. The planets were lined up for the Jerusalem artichoke and AEFS.

Fred the Second, Fred Hendrickson

Now, let’s talk a bit about Fred, because the key players in this story are really interesting characters. While Fred had an uneventful life prior to AEFS, he was a lawyer and had been divorced after hyperfixating on numerous ‘world-shattering’ business plans that failed to get off the ground. In 1972, on his second marriage and nth job, Hendrickson underwent a religious conversion. On April 2, he believed he came to know Christ. Hendrickson reformed his life. He gave up drinking and smoking and refounded his marriage in Christ. The conversion further intensified Hendrickson's sense of being elected. This Moses-like belief colored all his thoughts. While adopted by his parents as an infant, he now believed himself to be adopted by God as an adult.

Hendrickson, as a prophet, believed he would help complete God's covenant with America. Hendrickson never waivered in his belief that America was the new Israel and he was one of its prophets.

Hendrickson's God spoke directly to his people, promising to heal them and to return them to His Kingdom. His God was intent on restoring America's rural people; they were the object of His covenant. Hendrickson, much like many midwestern religious leaders at the time, believed the time of Christ's Second Coming was at hand. Hendrickson remained in Rapid City for the next nine years. There he practiced law and sold real estate, doing a lot of legal work for marginal farmers, indigenous peoples, and the poor. On the surface it appeared Hendrickson had found the stability he craved. His marriage held. His belief in God was unfaltering. He was filled with enthusiasm.

Hendrickson remained spiritually restless, and he continued to believe a unique mission was in store for him. At a Pentecostal meeting in the Twin Cities in August 1973, he interpreted a burning sensation in his palms as a sign of God's special calling. In December of the same year, after reading the Bible, he awoke from a nap and again experienced a burning sensation in his palms. On this occasion, Hendrickson believed God was speaking directly to him: "I am your God. You are to be my spokesman to my people—a prophet for this day and age."

Alternative Energy

In 1978, Hendrickson focused on a new idea to make a dollar, to serve God, and to save the nation. He turned his restless energy and attention to the field of alternative energy and, more specifically, the on-farm, alcohol-fuel industry. His first project, which existed only on paper, was a design for a company that would grow vegetables, utilizing geothermal energy. In his hyper-obsession, Hendrickson devoured all the information on alternative energy he could get his hands on. He even confessed to having become "a great reader of Mother Earth News," where he encountered for the first time what he took to be the revolutionary notion that renewable fuel could save both the nation and its farmers.

At this point, he started to advertise himself as an "Agri-Business Concept Developer, specializing in Alcohol, Wind, Solar and Thermal Energy and Agri-Business Development." During 1980, he quickly left his stable work and Hendrickson feverishly occupied himself with a wide variety of start-ups aimed at the development of an alcohol cooperatives and the construction of alcohol plants. One particular project was on site in South Dakota called Igloo. At the Igloo site, a former U.S. army ammunition dump in western South Dakota, Hendrickson conjured an ecological vision of a totally self-sufficient farming system.

The concept was to create a biological counterpart to one of those perpetual motion machines. The waste from grazing cattle would be used to produce methane; steam-generated energy would be used to make alcohol. Aquaculture, fish farming, tree farming, biomass crops—including amaranth and fodder beets —all had their place on this farm.

Hendrickson never thought small. With a protractor, he circled on a state road map the tillable land in South Dakota as if to claim it for his own by virtue of his unique vision for it. Hendrickson credited the state with 66 counties, 77,000 square miles of land, and 50,000 farms, averaging 920 acres each. Of those, he had a plan for 27 counties, 27.5 million acres and more than 200,000 people. I’m not going to go further in detail– it’s lunacy, and to no one’s surprise, he was unable to get a loan.8

In 1980, Hendrickson's conversion to the Jerusalem artichoke followed. Hendrickson attributed this conversion to his discovery of how wonderfully six Jerusalem artichoke plants grew in the alley behind his Rapid City home. In October 1980, Hendrickson came across an article on the Jerusalem artichoke in the North Dakota Farmer that so moved him that he proceeded to telephone every contemporary reference mentioned in it. By the spring of 1981, in a special report to prospective customers, Hendrickson declared the Jerusalem artichoke to be "Energy Farmings' answer to OPEC."

Hendrickson ordered Jerusalem artichoke seed and began encouraging farmers to experiment with it. By that summer, Hendrickson considered himself an expert on the Jerusalem artichoke and did not hesitate to publicize its superiority to corn and other plants as a potential source of alcohol.

James Dwyer

With the failures of the Igloo project, which he blamed “Big Oil” for its inability to get funding, Hendrickson moved east to Sioux Falls, South Dakota. There, on the edge of corn-rich but crisis-stricken southwestern Minnesota and northwestern Iowa, Hendrickson would seek to fulfill his prophetic role. By the time he moved to Sioux Falls, Hendrickson had exhausted his resources, the resources of fellow believers, and the patience of his creditors. Unable to live by ideas alone, Hendrickson desperately needed, as he had with his past projects, a partner with cash. Enter James Dwire. Hendrickson had been acquainted with Dwire since he had offered to do construction work for the aborted Igloo project.

In late February or early March, before Hendrickson moved to Sioux Falls, he received a call from Dwire, a call that he considered providential. Hendrickson was ecstatic when Dwire, whom he perceived to be a successful businessman, decided not just to plant one acre, but half a semi-trailer load of seed, enough for twenty acres. The seed cost a thousand dollars per acre. Nearly beside himself, Hendrickson ordered a full load and began to sell Jerusalem artichoke seeds to farmers, whose enthusiasm in many cases equaled Hendrickson's. Dwire, like Hendrickson, saw a need for cheaper and alternative fuels for his energy-intensive construction business. He had already experimented in his home and office with wind and solar power. He also nodded in agreement when Hendrickson prophetically proclaimed that unless something was done, and done soon, the Christian farm was doomed and the nation would be lost.

Hendrickson and Dwire convinced themselves that they were destined for each other: Hendrickson had the ideas, and Dwire had the means; he owned a company generously estimated to include seventy-five employees, twenty vehicles, and capital.

Hendrickson interpreted everything as part of God's providence. In one instance, he wrote Dwire that God had guided them to the right accounting firm; in another instance, he wrote Dwire that only God could have led him to make a visit to a fructose-processing plant. Hendrickson concluded that a new age was upon humanity, and he declared to Dwire his intention to form a Christian Farmers Association to organize all American agriculture around God and the Jerusalem artichoke.

The new association would fight the international bankers and the much feared Trilateral Commission, a consortium of eminent private American, European, and Japanese business leaders whose goal is to foster economic cooperation.9

Big New World Order energy. The precursor of that term, in fact. Not that he invented it, but he retooled it to advance his interests. The commission was interpreted by a large part of the American political fringe, especially in the countryside, where conspiratorial theories historically abound, as the secret and real source of world economic dominance.

When they decided to incorporate, the company would be called the American Energy Farming Systems. Dwire would be president and chief financial officer, while Hendrickson would serve as secretary and vice president of research. Their original plan was to market seed to only two hundred growers in a six state area. At the first artichoke growers convention, Hendrickson summarized the views that led him to found AEFS. He declared it was the task of Jerusalem artichoke growers to save America and the family farm from “Arabs”, who were villianized as controlling the world's supply of oil and seeking to destroy Israel and Christendom. For him, the Jerusalem artichoke was indeed "the weed that whips OPEC."

James Dwire believed Hendrickson not only could build him an alcohol plant and put him in contact with the alcohol fuel movement but was, in truth, a kind of prophet. Dwire had hardly heard Hendrickson's pitch before he decided to make him his partner. Dwire didn't bother to check on Hendrickson's background. And here’s his recollection of it– "I sized him up," Dwire recalled, "as we in the Midwest do: by his word and a handshake." He didn't even bother to make a few telephone calls to Rapid City to find out why his prospective co-owner and director of research, an attorney by trade, was no longer practicing law and was broke.

While Dwire was a business man, he had inherited a business, and– I know this is gonna shock you– ran it into the ground. When Fred Hendrickson showed up, he was past due paying contractors for work, and had bet the farm on farmland increasing in value, despite the fact farmers were going bankrupt across the country. Prior to 1979, Dwire owned only a small farm. From 1979 to 1981, as the business started and quickly exploded, Dwire purchased eleven pieces of real estate for rental purposes. The purchase cost of these eleven properties exceeded a million dollars.10

If rents from his lands rose and if his properties and companies retained, or increased, their value, Dwire would be fine. If things went badly—that is, if interest remained high, if real estate lost its value, and above all, if AEFS ran out of cash—Dwire would crash to the ground and the cleverest accountants wouldn't be able to put him back together again. Without AEFS cash his whole economic kingdom would disintegrate: he would lose his property; he would no longer have his handsome AEFS salary; there would be no work for Dwire, Inc., or his other companies; he would lose the preferential rent of two hundred dollars per acre he received from AEFS on his farm land; his Jerusalem artichoke seed would not command a premium price; and, furthermore, he would be unable to meet the numerous annual and balloon payments he owed on his property and payments on debts owed his brothers and sisters on the settlement of his father's estate.

Brought up as a Methodist, Dwire became a born-again Christian. He no longer drank; he took the television sets out of his home; he prayed before his meals even when out in public; and he openly incorporated faith in God into his speech. Dwire believed, as did Hendrickson, that their meeting was providential.

Dwire had previously developed some fringe beliefs, and would fit into the broad category of a survivalist at heart; he believed energy independence was the key to saving the nation's heartland. Arguably, Dwire's search for energy independence, more than anything else, explains why Dwire was willing to join Hendrickson in creating AEFS. At the time he met Hendrickson, Dwire was preoccupied with finding an inexpensive alternative to the diesel fuel used by his companies, which had caused him to lose massive amounts on major construction jobs, because, as we’ll see, he had very little understanding of business fundamentals.

Now, predictably, any company Dwire and Hendrickson started would be more about promotion and sales than science and technology. The fact that Hendrickson could be responsible for the company's development of alcohol plants and other research should make that pretty obvious. If Dwire had had even a minimal knowledge of crop science, he would have realized from the beginning that there was simply no way an outcast plant could be transformed into a major crop for the production of fuel in a three-year period. Common sense and agricultural knowledge dictate that to turn any plant into a major crop requires years, even decades, of laboratory, genetic, agronomic, and market work. Among many other required conditions, not only did they need a potential niche in the market but the means of industrial processing, a large buyer, faithful and risk-taking farmer-suppliers, and luck itself, which might give the crop a chance to succeed. All this is shown by the soybean's four-decade development from a small and growing feed crop to a major oil crop. Despite the soybean's full importance to the agriculture of southwest Minnesota and the Midwest, Dwire knew little of its history in particular, or the nature of crop development in general.

Sometime during the first six months of the company's existence, it finally dawned on Dwire that Hendrickson was "all talk and little show." Dwire also became aware how much of AEFS's scientific research depended on a single scientist, namely, Wayne Dorband. Dorband, an assistant professor at Augustana College, was himself as much an entrepreneur as a college teacher or scientific researcher. Dorband had received his Ph.D. in fisheries resources from the University of Idaho in 1980. Prior to earning his doctorate, he had done some work on alcohol fuel as well as on limited agronomic research projects on wetland areas.

Before going to work for AEFS, Dorband had no knowledge of the Jerusalem artichoke and little or no knowledge in specialized fields associated with crop development. Basically, what Dorband essentially did for AEFS was "wear a white coat." He provided a quasi-legitimacy for a company of amateurs. In Dorband’s defense, he did try to carry out some legitimate projects. He gathered a large collection of articles on the Jerusalem artichoke. He carried out preliminary evaluations of the feed value of the plant. Also, he undertook a large but essentially uninstructive literature search, devised a very primitive survey for collecting field data from growers, supervised AEFS's experimental acres, and offered agronomic advice on weeding, harvesting, and pesticides. Also, he wrote a significant, if not the greatest, portion of the company's more important sales literature. This literature later was at the center of the Minnesota attorney general's investigation of AEFS. Today, Dr. Dorband doesn’t advertise his work with AEFS, but is still active in the alternative agriculture community.

While Dorband likely knew how fucked they were, Dwire and Hendrickson sincerely tried to provide evidence for their efforts. For instance, they identified some prestigious scientists who studied the Jerusalem artichoke; entered into a lease-purchase agreement for the use of a local alcohol plant; started a dehydration project; approached a few large companies about research on and purchase of the Jerusalem artichoke; and took a trip to France to see what positive use the French purportedly made of the Jerusalem artichoke. Dwire and Hendrickson passed off their efforts as part of company research.

At the founding of the company, both Hendrickson and Dwire were justifiably giddy with success. More farmers wanted Jerusalem artichoke seed tubers than they had ever imagined. Money rolled in. Hendrickson believed he was leading the nation and himself to prosperity. Dwire was equally enthusiastic. He was making money. AEFS provided work for his construction companies. He met his payrolls, hired his friends, and started to purchase new properties. Now was not the time for either of them to question their creation. Throughout the company's history, ignorance and naivete protected the consciences of Dwire and Hendrickson.

But they should have known better. At one point, Dwire fired AEFS's accountants rather than heed their warnings about his large borrowings and the company's serious cash shortage. Dwire explained his action by saying that the accountants didn't classify seed contracts paid to AEFS as income until the seed had been delivered.

"So you know, one is a debt and one is a credit, and I don't understand the two terms that well, but they were saying it was a loss and actually we had this money in the bank and by my private projection we were a profitable organization. We were basically a cash basis organization. Actually, we were a cash rich company."

-James Dwire

So the key to their incredible growth was tied specifically to its pyramid-scheme-adjecent model. It’s also why they had boatloads of cash on hand early on. AEFS designed their business in a way that made a lot of sense, if you had a business model in place, but was ]based on the most wild fantasy possible. Their contracts with first year growers was stemmed in the idea that they would guarantee to buy the seeds from their first year crops. They promised that for every dollar spent on seed, fifty cents would be kept back so the company would have the resources to buy growers' seed. They not only offered the growers 50 percent for AEFS's pooled sale of their crops, but also offered them an additional 15 percent for all completed sales they made from their own fields. 15 percent meant that the grower-sellers would make an additional $3,600, or about $15,000 in 2023. This contract meant, with just a little more figuring, that three standard sales would pay for their contracts and still leave them with thirty thousand pounds of Jerusalem artichoke seed left for future sales.

Basically, buyers paid a hefty premium for the guarantee that their product would have a guaranteed buyer– AEFS. They were charging seed costs that were 100x higher than corn, but with the promise that they would sell at least half back to AEFS at 1000x higher premiums than corn on a commodity market.

So they had a whole bunch of money that wasn’t technically theirs, but for promised future sales. They had a ton of positive cash flow, even though a bunch of it was promised to go back to the sellers.

Who Bought in?

Who was buying seed only to get their money back the next year? There’s a couple categories, and I’ll make this part quick. It was People who were afraid they were going to miss the boat on the next soybean, folks who figured it was worth trying to profit on marginal lands, people who were about to lose the farm and figured it was one last hope. Of most interest for us are the last two; the religious buyers, convinced it was a crop from God. Many of these religious believers stuck with the crop and with the company to the very bitter end. For example, when legal investigation of AEFS's sales claims for the Jerusalem artichoke came to light, one such believer, Thomas Sanger, wrote to Jerry Knapper that the Jerusalem artichoke was an answer to a prayer and AEFS itself was an agent of God's providence." Showing that his faith was not entirely innocent he added, "I also have some thoughts and ideas about forming a co-op or an association that would remove the concept of us being a 'pyramid type selling scheme.'

The last group were the people who recognized what it was, a pyramid scheme, and tried to make money on it before the bottom fell out. But it was hard to not believe with the profits AEFS was making that surely the business must be real given they were making 6 million a month by January of 1982. In classic Trumpspeak, Dwire concluded that “there would be more than enough money to always pay and they call that robbing Peter to pay Paul but it is a continuation of business, and that describes it."11

So we’ve talked a bit about Evangelicalism and its role in AEFS’s model, but it’s important to understand why this was so effective. Experiencing a great resurgence in the 1960s and 1970s and emerging into the national limelight during the Reagan presidency, evangelical Christianity provided an enthusiastic faith that believed that God would not let his vision fail, so if your vision was from God it would succeed. AEFS belonged to the emerging phenomenon of a new kind of direct sales organization, something we can call "charismatic capitalism." In direct selling one can work and serve God and country at the same time. Direct selling is basically a quasi-patriotic activity: God and the nation are served by the pursuit of direct sales. In this way the American ethic contributes to a generalized desire to go out into the world and make money.12

Now, AEFS supporters dedicated themselves to saving the countryside from the nation's swollen cities and foreign dependence. They asserted that their own calling was "a calling beyond and above commerce." AEFS was not just a company but a "family of believers" who believed in God, America, the family farm, and Jerusalem artichokes.

This was no more apparent than in AEFS's first National Growers Convention in June 1982. The convention was titled "Energy Freedom for the Eighties." More than a thousand people attended the convention. The convention hosted lectures, show-and-tell sessions, and small alcohol fuel demonstrations, suggesting how the Jerusalem artichoke would be commercially transformed into fuel and feed. One South Dakotan, James Fish, recalled, among other things, being moved by one of the presenters who described how she had died and spent time in heaven before returning to this earth.13

What exactly did that have to do with sunchokes? It was a televangelist event, without that annoying Bible reading. Don Sheenan, a member of AEFS's sales staff and author of a pamphlet called "Shut Up and Sell," spoke about motivation. He started his talk claiming that "the Lord had never denied me one thing in my life." He suggested that "sales was the key to the 1980s" and concluded with a novel appeal to the Holy Spirit: "Anoint me with artichokes and set me on fire."

The OG Televangelist Toots his Horn

Enter Reverend Lowell Kramer, a minister who played an important role in AEFS, and also, fun fact, one of the world’s first televangelists, gave a motivational speech in the spirit of his ministry's motto, "Dedicated to Serve God and Man." He introduced himself by elucidating the anagram:

EVANGELIST: "E = Energetic, V = Vibrant, A = Anointed, N = Notable, G = Great, E = Electrifying, L = Lively, I = Innovative, S = Sensational, and T = Terrific."

After explaining how we all like and need money, he spelled out the anagram MONEY: M means God is for me; I must live in his plan. O stands for the opportunity provided to me by the Jerusalem artichoke. N expresses the necessity of surrendering ourselves to God. E equals the energy within you. It is greater than all OPEC's power and it will serve your God, nation, and generation. Y is for you, the one who must apply his faith. The message was clear: Trust God, buy Jerusalem artichokes, and become rich.

We could unpack Kramer further, but all you need to know is that he was a televangelist who loved jewelry, started a nursing home chain which was later investigated and shut down by the SEC. In a signed statement in February 1975, Kramer indicated he was worth $2.5 million, with an annual income of $220,000. However, he told SEC examiners that this was simply a projected income meant to impress bankers (which, by the way, is very illegal). It also did not conform to his income tax filing for 1974, in which his adjusted gross income was $26,864.14

At least in general terms, Dwire and Hendrickson knew about and discussed Kramer's problems at Challenge Homes. In fact, Hendrickson had represented clients who held Challenge Homes bonds. Yet they chose not to investigate Kramer's background, because, fucking obviously they didn’t.

While AEFS was busy trying to leverage its Evangelical identity to justify its ridiculous proposals, it actually went out and made religious faith part of its sales pitch. Its first sales list was the membership list of a regional radio show Prayer Power, hosted by a guy named Pastor Pete. Coincidentally, the first employee AEFS hired was John Peterson, Pastor Pete's son.

The Reverends Jerry Knapper and Lowell Kramer were hired because they could preach; Richard Spencer, the head of AEFS's research team, attended Dwire's church, the Marshall Evangelical Free Church.

So basically, AEFS dressed itself in Christian trappings. The workday often began with a prayer service and organ music. Carried away with the power of prayer to serve self-interest, one AEFS official prayed for the failure of the corn crop so farmers would be led to find their way to the true crop, the Jerusalem artichoke.

AEFS offered the buyer of Jerusalem artichokes a chance not just to make a profit but also to enroll himself in a "spiritual" family, a veritable movement, a kind of church. Buyer and grower alike, the pitch ran, were joined together in a project on behalf of self, nation, and God. AEFS used other promises to attract growers. Its salesmen commonly used the specific promise of an escrow account to make AEFS seem as much an investment as a purchase. They promised that for every dollar spent on seed, fifty cents would be kept back so the company would have the resources to buy growers' seed. Integral to AEFS's pitch was the notion that growers were at the forefront of an important but risky undertaking; if it worked out, they would receive the generous reward they deserved. This sales principle of well-rewarded risk is identified in scams such as the "Spanish-prisoner scheme," whose come on is "Give us a little money now, and you'll get a lot of money later."

One common AEFS sales line was the "train-is-leaving" pitch, which was inseparable from the buying hysteria that surrounded the plant. In the spring of 1982, vice president of sales Jerry Knapper informed the press, "This thing is going like wild fire," as he pointed out that in less than a year the company had hired forty full-time sales staff and three hundred to four hundred part-time staff. One of its more notable ads had French farmers growing more acres of Jerusalem artichokes than there were acres in France, when, in fact, there were fewer than 20,000 acres of Jerusalem artichokes under cultivation in France at the time. Other ads repeatedly suggested that industrial uses of the Jerusalem artichoke for sugar and fuel were imminent. One regional sales representative encouraged his salesmen to take along on sales trips such Jerusalem artichoke products as spaghetti, pellets, and jars of alcohol and fructose (in crystal form). The intended implication: The jars contained products made from Jerusalem artichokes, which they were not.15 Also, according to the Minnesota attorney general's office and other attorneys general's offices, AEFS's standard mathematical pitch was patently false.

AEFS contended that it takes a thousand pounds of seed tubers (at a dollar a pound) to seed an acre, but each acre yields, they most exaggeratedly claimed, forty-five to sixty-five tons of tubers. For context, an acre of corn, the highest producing crop on the earth, produces roughly 2 tons of kernels. On this basis, conservative estimates would lead a grower to believe that ten acres (the average acreage of growers) would net nearly half a million dollars a year. If AEFS attained its goals, which included selling 20 million acres of Jerusalem artichokes in the next five to seven years, phenomenal growth and profits lay ahead.

The nearly five hundred artichoke growers who had contracts for the first three years with AEFS would produce (at a 30 to 1 ratio) by 1984 enough seeds to supply the seed needs of 450,000 additional farmers, more than double the total number of farmers in North and South Dakota and Minnesota combined. If these 450,000 additional farmers grew seed tubers in similar amounts, North America itself would be inundated by seeds.

Despite this obvious issue, a euphoric and megalomaniacal vision of the Jerusalem artichoke's future kept AEFS's phones ringing off their hooks throughout 1982. To take advantage of this "wonderful offer," which allowed farmers to make more than $40,000 an acre, they needed only to accept AEFS's standard three-year agreement. The grower, the pitch ran, would buy seed for ten acres for $12,000—which was calculated at 1,000 pounds of seed per acre at the cost of $1.20 a pound. For its part, AEFS would become the grower's exclusive marketing agent for the following three years. AEFS would receive a marketing developer fee of 50 percent of all gross sales of the seed tubers harvested in the fall of 1982 and the spring of 1983 and a 40 percent fee on all crops grown for the following two harvests. In addition to promising the development of machinery to harvest the artichokes and furnish custom planting, AEFS promised to make its "best efforts to market the grower's crop ... to develop a program of research on improved strains . . . and of use of [the crop] as an alcohol-fuel crop, a fructose sugar crop, an edible plant for humans and a livestock and poultry feed.16

This wasn’t the only way AEFS created the illusion of future success; they also used quasi-institutional ads to convince the growers that it had significant research under way to unleash the potential of the crop and to establish its best varieties. It invited its growers to participate in the agronomic study of the crop. AEFS tried to make the growers believe they were joining a family: AEFS celebrated growers' birthdays and anniversaries. It sponsored contests for the tallest plant and the best school speeches on the artichoke as a future crop. It solicited recipes from growers' wives and involved them in trading Jerusalem artichoke recipes, an experience AEFS promoters shamelessly labeled "Breaking Loose."

AEFS supplied growers with a chance to win recipe books, to obtain free samples of pelletized Jerusalem artichokes and Jerusalem artichoke flour, as well as to purchase Jerusalem artichoke T-shirts and Jerusalem artichoke buttons, one of which announced "Jerusalem Artichokes could keep you in farming." In Minnesota, AEFS drove a large bus from farm to farm to sell Jerusalem artichokes and it used an alcohol fueled car for the same purpose. Not powered by their own alcohol, of course. They even partnered with some independent news organizations to publish articles like, “Ford’s Better Idea, Alcohol Fuel Finds Home In Brazil”.

Now, bigger buyers were often flown in to see their research facility and so on. On these flights, visitors were often deceptively shown the large Marshall corn processing plant as belonging to AEFS. Once on the ground, the visitors were given a tour of AEFS's main sales building and its displays, company headquarters, Dwire's fields of artichokes at nearby Lynd and, on occasion, a local alcohol plant that AEFS was negotiating to purchase. At the end of the tour, after giving prospective growers a chance to sign on the dotted line, AEFS provided them with a smorgasbord of fresh artichoke foods before their return trip home. This last snack occasioned many a sly smile on AEFS employees' faces. They knew their "windy fruit's" power would exert itself before the prospective buyers completed their flight home.

The Beginning of the End

Unsurprisingly, warnings and accusations about the crop and the company came quickly. As early as October 1981, a University of Minnesota Agricultural Extension Service memorandum to regional agents in Southwestern Minnesota cautioned, "A firm in Lyon County promoting the growing of Jerusalem artichokes as a crop overestimates the yields of the plant as well as the plant's potential for conversion to alcohol fuel and sugar, and even human food." In April 1982, the Extension Service in another memorandum cautioned that the much-touted claim that the Jerusalem artichoke got 90 percent of its nutrition from air, sunshine, and water was true not only for the Jerusalem artichoke but for all plants.

By December 1981, Minnesota commissioner of agriculture Mark Seetin openly charged that no research in the past fifty years supported AEFS's claims about the yield of the Jerusalem artichokes, and he announced his intention to ask the Minnesota attorney general's office to examine AEFS as being engaged in pyramid sales. The attorney general's office began an inquiry into AEFS's business practices in light of possible pyramid schemes, monopolies, and fraud. On December 9, 1981, the Sioux Falls Argus Leader bannered its state section with the headline, "Jerusalem Artichoke Production Question." The paper quoted the state director of energy policy, who found the contrast between the ten-dollar-an acre cost of seeding corn and the thousand-dollar-an-acre cost of seeding Jerusalem artichokes ironically worthy of AEFS's motto, borrowed from Sam Adams, "Risk is the price you pay for opportunity."

A month later, in January 1982, a critical article was published by The Farmer, an influential agricultural paper which labeled the Jerusalem artichoke a highly speculative venture in light of the fact that there were no existing new markets for the crop. He quoted one of the nation's most knowledgeable artichoke advocates, Tom Lukens, who claimed that markets for the crop were several years away by even the most optimistic estimates. He also quoted Jerusalem artichoke advocate, developer, and speculator Thomas Reichert, who suggested that AEFS might be growing the wrong variety of Jerusalem artichokes; the earlier-maturing Columbian variety might prove more appropriate in northern climates, which have shorter growing seasons, than the French Mammoth White sold by AEFS.

It gets better. Anticipating investigations into possible monopoly charges against AEFS, the paper pointed out the profound price discrepancies between the $1.00 and $1.20 a pound charged by AEFS for Jerusalem artichoke seed tubers and the 18 cents to 23 cents a pound it sold for in many fresh produce markets and the 40 cents to 50 cents a pound being paid for tuber seedstock in Washington state, which was, surprise– where AEFS got its original seedstock from.

Further, South Dakota securities concluded its review, which had begun in December 1981, with the finding that AEFS was selling securities. In March 1982, the state of South Dakota, in an order to cease and desist, prohibited AEFS "from making any future sales or offers of Jerusalem artichoke tubers" until it properly registered itself in the state. In all of this, they forgot to register the company with the state.

While South Dakota lifted its ban in July 1982, it required the company to offer its South Dakota growers a chance to rescind their contracts. AEFS agreed. As was the case in subsequent rescissions in Iowa, Nebraska, and elsewhere, its growers—much to AEFS's pride—were not interested in the offer. Only one South Dakota Jerusalem artichoke grower out of approximately thirty took advantage of the rescission offer. At the meeting between growers and a representative of the consumer division, the majority of growers, according to Dwire, literally laughed at the consumer division representative. They told him to get his nose out of farming.

In December 1981, the Minnesota Attorney General began an investigation of AEFS. The owners of AEFS believed the investigation to be part of a conspiracy against them. Hendrickson suspected—and did until the day he died—that behind the attorney general's investigation were the world oil cartel and the world's giant grain merchants.

In response to the demands of the attorney general's office, and upon the advice of its attorneys, AEFS rewrote its literature, altered its contracts with buyers and growers, and designed and redesigned its multiple programs with growers. It also abandoned its effort to define itself as a shared enterprise, since not to would have made the company subject to the laws regulating securities. Also, it rewrote its contract to avoid being judged a monopoly. It had to restrict itself to selling seeds to its buyers, without seeking to control the future stock, sale, or price of seed. Additionally, AEFS had to alter its basic sales strategy if it were not to be judged a pyramid-sales scheme. It could no longer link the benefits of purchasing a seed contract to future sales of the seed, sales of salesmanships, or the sales of distributorships, all of which, as the Attorney General pointed out, are "hallmarks of a pyramid-scheme or multilevel distributorship."

So they jumped through the hoops required, but their legal dilemma persisted. If it were to satisfy the attorney general's office that it was not a security, it had to sell tuber seed and tuber seed alone. Yet if it were to avoid being a pyramid scheme, it had to demonstrate that Jerusalem artichoke tuber seed had a value. The question of the plant's value confronted AEFS with one insurmountable problem. While hypothetically AEFS could satisfy the law by showing that it was not to be a security, a monopoly, and a pyramid, it could not—try as it would—identify a market for its product. This failure meant that in the end all AEFS had to sell was the blue sky. AEFS could not escape its day of reckoning with the attorney general.

Unsurprisingly, they threw everything at the wall to see what would stick. For example, AEFS leased a small alcohol plant in Marshall that never succeeded in processing more than a cup or two of alcohol. Also, the company tried, unsuccessfully, to turn a failed Marshall food processing plant into a Jerusalem artichoke processing plant. The impure and fibrous Jerusalem artichoke, as one worker noted, defied the processing plant driers as much as it did the stills of the alcohol plant. Following the fashionable concept of biomass conversion, Hendrickson started an offshoot company, Bio-Markets of America, whose purpose was to convert the Jerusalem artichoke into an energy source with zero success.

Despite all of this, one thing held: the fiction that on the open market Jerusalem artichoke tuber seed was worth $1.20 a pound. This fiction was maintained up to the final hours of the company's existence, when AEFS failed in a bid to sell Jerusalem artichoke tuber seed to Archer-Daniel-Midlands for just five cents a pound, a 96% drop in value, to the 1 company that even offered to buy them. But, that wasn’t enough for them to sell. The fiction of $1.20 a pound was terribly important. It was the promise that brought a river of money into the company. It secured the value of the company's paper transactions; it provided a rational measure to their crazy world of taking advances and draws and then paying them back in seed or notes on future seed.

So they were using the valuation of the company’s profits based on this arbitrary figure, and then could borrow against their future earnings, for, well, whatever they wanted. Now, in the aftermath of AEFS's bankruptcy, – sorry, spoiler alert right there– Dwire publicly explained the failure of the company as a problem of "government interference, bad press, employees, and hyper-growth."

Now, some of the employees, unsurprisingly, have a different perspective on why the company failed. Mark Hughes, an agronomist, considered the company flawed in conception and practice, and he believed that company officials either knowingly made false claims about markets for the Jerusalem artichoke or were stupendously stupid– his words, not mine.17 The production of alcohol from the Jerusalem artichoke wasn't yet feasible even from an engineering point of view.

E: That is my favorite takedown; it was flawed in conception and practice.

Pat Derner, Hendrickson's colleague who was expected to help create markets, lacked a chemical engineering background and had little knowledge about processing. According to Hughes, no one stopped to think twice. They had no foresight. The seed program was a sham and the seed should not have been spread all over the country. There was no disease control; they just didn't know agriculture. They knew they were spreading sclerotina, a plant disease which is found in beans and sunflowers, and they did nothing about this.

So one thing we haven’t talked about is how businesses have requirements around things like what’s called ‘arms length transactions’, which basically means you can’t use business assets for personal stuff, and doing business in "good faith and fair dealing" and that they take "due care" in managing their affairs.18 The basis is that business prohibits owners and managers from competing with their own corporation and having interests that conflict with those of the corporation. Furthermore, fiduciary trust requires that a director or officer have undivided loyalty to his own company and be "influenced in action by no consideration other than the welfare of the company." Fiduciary trust in Minnesota law specifically holds directors liable for losses or harm to the corporation as a result of breaking fiduciary obligations.

As early as October 28, 1982, Hendrickson, in one of his many lengthy letters to Dwire, acknowledged that there was no meaningful market for the Jerusalem artichoke as of then and stated that "time is not on our side." Hendrickson further worried about the legality of their practices, acknowledging that he had been "equally neglectful of attending to [AEFS] details”. A lot stood in the way of their taking this advice, primarily their presumption that AEFS's cash was theirs. And the tendency to treat the company's profits and opportunities as their own was given greater impetus by their decision in the fall of 1981 to operate under Subchapter S of the Internal Revenue Code. Subchapter S meant that they were no longer treated as a seller of securities but rather as a partnership that was assessed taxes solely on the basis of profits they took out of the company. In the tax world, we call S-Corps pass-through entities, because their earnings basically go directly on your tax return. Further, at this time, there was massive exploitation of “distributions” to bypass payroll taxes, which undoubtedly was taken full advantage of by AEFS.

In the Words of Dwyer, It’s time to Pay Paul, or Something

In the spring of 1982, they got rid of their first auditing firm when they complained strongly about AEFS's accounting and business practices. Among the things pointed out in the audit was the fact that the owners had taken from the company a million dollars more than it had earned: $945,000 had gone in advances to Dwire; $142,264 had gone to Fred Hendrickson. In July 1982, they hired another auditing firm, who, surprise, said the same thing, and whose well-paid-for advice was also ignored. In his grand jury testimony, one of the auditors testified that his firm's coaxings, pleadings, and warnings about irregular withdrawals and the need to pay back advances went unheeded. Hendrickson and Dwire would not commit themselves to a schedule of repayment, and they even canceled the completion of a financial statement in the spring of 1982.19

And the IRS was like, sorry, not sorry, here’s your bill. But before we get there, in the spring of 1983, the business still less than 18 months old, with AEFS facing a severe cash-flow problem and the attorney general breathing down the company's neck, they had another emergency audit. On the basis of their work, they penciled a note that declared AEFS to be "inauditable," and he went on to identify a host of business violations.

The firm stated that the owners mixed company and personal funds, made frivolous use of AEFS money, used corporate money for personal advances and payment of personal credit cards, showed no accountability for funds borrowed, lacked job descriptions, didn't regulate purchases, and failed to keep proper books. As if that weren't enough, Ribbens remarked that he was unable to identify AEFS's practices with a common ownership and even cautioned that the company might still be considered a pyramid.

No sooner did money begin to flow into AEFS coffers than the owners began to treat it as their own. On October 2, 1981, three weeks after its founding, the company's checkbook was already overdrawn. On October 30, 1982, Dwire withdrew $10,000 from AEFS for personal needs. From the company's inception to its filing for bankruptcy, Dwire took $1,700,000 in draws, loans, and advances, while Dwire, Inc., took approximately $1,600,000 for services and other uses. Far more modestly, Hendrickson, who began with small withdrawals ended up a year and a half later having taken $770,000 from the company for personal expenses. They also started themselves at salaries of $75,000 per year in the fall of 1981, but by the fall of 1982 they were rewarding themselves with salaries of $250,000 a year, making themselves among the best paid managers in Minnesota.

So we talked about the $1.20 a pound figure. This proved a useful device to take cash out of the company. They counted their past, present, or future sales against any draws and advances they took. This proved an ingenious means for them to use company funds to put down payments on personal farms, which they in turn rented back to the company at the handsome rate of $200 an acre. While ostensibly serving the justifiable ends of crop research or of furnishing AEFS with a needed seed bank for growers who had received poor seed or lost seed to adverse weather, it was a means for Hendrickson and Dwire to own several farms.

In a grand jury testimony, one employee claimed that Dwire, Inc., bought seed at 25 cents a pound in Monticello and then sold it again, under the name of Dwire, Inc., to AEFS for 50 or 60 cents a pound. When AEFS needed services, Dwire's corporations, his family, or his friends met those needs. Dwire had AEFS employ his wife, who had the power to sign AEFS checks, two of his three sons, his uncle, his brother-in-law, and friends and acquaintances. Dwire, Inc., which charged AEFS premium prices, reciprocated by borrowing $600,000 in operating loans from AEFS, without offering any assets to secure the loans. These were absolutely not arms-length transactions.

In a far more complex scheme in the spring of 1983, with Dwire's full support, Reverend Kramer created a lending fund for growers who were too great a risk to receive a loan from AEFS. Nominally under the presidency of his son Tim and bearing Kramer's spiritual stamp (it was called Challenge Fund), the fund provided Kramer a means to get rid of the company's excess seed at no cost to himself or Dwire. The fund gave seed to growers in exchange for interest on the seed and a two-year partnership on growers' future Jerusalem artichoke crops. Kramer turned Challenge Fund partnerships, and other partnerships, into more than $2 million of financial paper, which, at face value or discounted, could be used —inside or outside AEFS —to raise cash, pay debts, or even make religious contributions.

So they sign a no-cost-down loan with people with bad credit, and then use that as collateral to do whatever the fuck they want, all based on the $1.20 a pound figure they arbitrarily chose. In exchange for giving desperate farmers a chance to survive in farming one more day, Kramer and Dwire got rid of seed, earned interest, and created financial paper that, however dubious its value, had potential worth in that era of speculation. Kramer contended that prior to filing bankruptcy he had a New York "Jewish" firm willing to offer him as much as $1.5 million for the notes at a discounted rate of approximately 35 percent.

The nightmare was still collecting new problems, somehow. Jim Nichols—farmer, teacher, state senator & general AEFS hater— he was appointed commissioner of agriculture in January 1983 and pushed the attorney general's office to broaden its investigation of AEFS. Nichols couldn't bring himself to believe that a crop that cost its buyers $ 1,000 an acre for seed alone (in contrast to corn, that cost $10 or $15 an acre) and for which there was no identified market was going to help the troubled farmers. While numerous midwestern attorney generals' offices accused AEFS of overestimating the promise of the crop and of not disclosing the fact that there were no markets for it, its essential conclusions were that this was a case of "not such smart consumers doing some bad buying."

The Minnesota attorney general's office reached an agreement with AEFS. Without having to acknowledge wrongdoing on its part, the company would pay the state $40,000 in fines, change its sales practices, and offer its growers a rescission of their contracts. The rescission could amount to an $18 million payback. And this was the second time they had to offer buyers a chance to rescind their contract.

But unlike the last round where the farmers told them that they needed to keep their nose out of ag, the rescission offer got a surprising number of takers. This was due to the advance publicity given the settlement between AEFS and the Minnesota attorney general's office by a February article in The Farmer. Approximately a quarter of AEFS growers, nearly six hundred farmers, the great majority of whom were two-year growers rather than the original and more committed three-year growers, quickly accepted the offer. Now, unsurprisingly, with only $2 or $2.5 million in cash on hand, AEFS was unable to satisfy approximately $6 million in growers' claims.

Bankruptcy

They all knew it was coming. Since the late fall of 1982, Dwire, Hendrickson, and Kramer had already begun to prepare their own lifeboats. As the company's legal problems mounted and their efforts to transform the Jerusalem artichoke into a viable crop failed, each began to look beyond AEFS.

On December 31, 1982, Hendrickson took a cash advances and loans for over half a million. Kramer took $280,000 & Dwire, their leader, took $687,000 for both his business and himself. On the very eve of retaining a bankruptcy attorney on May 10, Dwire, Hendrickson, and Kramer took almost everything left in AEFS's coffers, which, by the best calculations of their prosecutors, totaled $686,000. Among their distributions, they gave their attorneys' firm cash for future legal fees & the accounting firm to handle the bankruptcy; the remaining $400,000 split among the 3.

On the evening of May 20, 1983, the annual assembly of AEFS Christian family of growers had its last supper. The company formally did so three days later, on May 23, 1983. It claimed that it had $19 million in unpaid debts and, with considerable exaggeration, that it had $11 million in assets. A few months later, when the federal bankruptcy court in St. Paul converted their Chapter 11 bankruptcy to a Chapter 7 bankruptcy, the court custodian claimed that AEFS had even less than a million dollars worth of assets.

Yeah, Trump is basically the poster child for this type of business sandbagging. Dwire and Hendrickson made the final days of AEFS a perfect case study of illegal actions they had learned up to then, as McLeod County district attorney Peter Kasal would charge in subsequent cases against Dwire, Hendrickson, and Kramer. After everything was said and done, the auditor for their bankruptcy estimated that of $26.2 M AEFS took in, James Dwire and his family received in cash or check $1.9M; Fred Hendrickson received $680,000; and Kramer, along with a few others we didn’t talk about received $2.3M, for a total of almost 5 million.

Alright, while that doesn’t sound insanely terrible, remember that every meal, every plane ride, every bullshit business expense– the cars, and so on– those were not cash or check received. While we don’t have a clue what those expense were, it’s easy to suspect they ate through 75% of that money on their delusion. As the growers became increasingly aware that something was wrong before the bankruptcy announcement, reacting to the Minnesota attorney general's findings, three-year growers sought an alternative path to AEFS. In June 1983, the Minnesota Artichoke Growers Association (MAGA) was formed in order to make sure Minnesota growers were represented at the July bankruptcy hearing.

Starting in early 1984, the government filed a succession of liens against Dwire's properties, even his house, for which AEFS had made payments towards his mortgage. Normal business stuff. They garnished $130,000 in funds held in a Colorado bank for Pegsons, a new contracting firm owned, as the name indicated, by Dwire's wife Peg and their two oldest sons.

Nichols, who pushed this investigation, left some really great commentary on his experience with the AEFS crew, saying that:

"Their sort didn't prepare for bankruptcy. They were not brilliant at laundering money.”

He found money stashed all over the place. He reclaimed insurance premiums and confiscated tax returns. An auction of AEFS's goods and some goods from Dwire, Inc., and Dwire's family was held in the fall of 1983 in the parking lot of AEFS's main corporate building. It netted another $350,000. But here’s where it gets good; wearing a bullet-proof vest, Dwire himself attended the auction. He mingled freely with friends and former AEFS growers, commenting on the rows of goods that once defined his and AEFS's fortunes. He even had a friend purchase a thing or two of his back.

AEFS's bankruptcy case was finally closed September 15, 1989. As part of the final settlement with bankruptcy court, Dwire had agreed to a nondischargeable debt of $815,000; Kramer, a nondischargeable debt of $250,000; and Hendrickson, a nondischargeable debt of $50,000. Kramer and Dwire couldn't, and didn't, pay their debts. Dwire, who on the eve of AEFS's bankruptcy owned several companies and farms, remarked "I haven't paid them anything yet. I don't have any money. I'm busted."

Despite all this, more difficult judgments lay ahead for each of them, as well as some final acts of stupidity. In the wake of declaring bankruptcy, Dwire, Hendrickson, and Kramer continued to scramble for money. They even boldly entered claims in bankruptcy court against AEFS for unpaid wages and seed deliveries.20

In the spring of 1984 attorney Peter Kasal summoned a county grand jury to investigate AEFS and its officers and managers. Initially they dismissed this investigation by the "small-time county attorney", especially when they compared it to ongoing investigations by the FBI, the Minnesota attorney general's office, U.S. postal inspectors, and the federal bankruptcy court.

Underestimating Kasal proved to be a serious mistake, however. Kasal had been pursuing AEFS's owners since the company's bankruptcy had cost several of his friends and acquaintances money. At least on the surface, it made little sense that a county attorney from a rural county sixty miles from the Twin Cities should pursue a criminal case against Hendrickson, Kramer, and Dwire when no one else did. Not altogether irrationally, the three men suspected that Kasal was the agent of someone else. They postulated that he was a pawn of Hubert Humphrey III, who, in turn, was an agent of Dwayne Andreas of the corporate agricultural giant Archer-Daniels-Midland.

Instead, Kasal had a simpler reason, outside of helping his friends; he was preparing to campaign for U.S. Congress against incumbent Vin Weber, a young Republican whose star had risen high during Reagan's presidency. At the end of October, the multicounty grand jury brought indictments against all three men. They were indicted for the diversion of corporate assets, theft, and theft by swindle. Dwire and Hendrickson were charged with additional theft counts.21

With these indictments in hand, Kasal and Newes were confident they would convict the three men. Their confidence, however, was crushed when they discovered that that very spring the state legislature had de facto repealed the criminal statutes defining the diversion of corporate assets by failing to include them in its redrafting of the pertinent sections of the statutes. Whoops.

A week before he was to go to trial, Dwire, out of money, pleaded guilty to the charge of theft by swindle. Dwire was sentenced to 180 days in jail with work release, which he would serve in El Paso, Colorado, starting in January 1988. For theft by swindle the judge sentenced Dwire to one year and one day of jail and five years of probation. The most recent record I could find on him, he had divorced and moved to California to start a new construction company.

If he never heard the word artichoke again, I think he’d have been happy. Now, Hendrickson was found guilty of theft by swindle and conspiracy to commit theft by swindle. While he succeeded on appeal in defeating the first of the two counts against him—conspiracy to commit theft by swindle —he could not convince a higher court to set aside his conviction of theft by swindle. The judge sentenced him to serve six months in prison.

Learning absolutely fucking nothing, Hendrickson, in the years following, continued to start new companies that were basically the same exact thing; cooperative farming around sunchokes for fuel production. Hendrickson prophesied that God exposed his people to seven years of famine to open their hearts. Hendrickson saw a new age for the American farmer amidst a world famine. The world would end soon, or— for some unexplained reason—within thirty-seven years, as he wrote on July 17, 1986.

In a 1991 interview, he worked on a canning line and stated that he now identified with the urban underclass. And I quote from the interview, “He wondered out loud if he were to be its leader. He thought so. Assuming history repeats itself, he suggested the workers would rise up in 1992, as they did in 1892.”

Our last good friend here, Reverend Kramer, was found guilty of theft and theft by swindle. Four jurors, including the jury foreman, who were interviewed a little more than a year after the trial, offered different reasons for their judgment. I only care about 2 of them, though. While one juror reported that another juror had held out against finding him guilty because he was a minister, she herself said that Kramer reminded her of Billy Sunday and he "looked like a city slicker." "That guy," another juror said, "just wasn't on the up and up."

Kramer went backing to hawking religious shit afterwards, and in later years, Kramer was concerned about the taking over of America by outsiders, including "the Jews," and believes that he was the victim of a massive vendetta carried out against him and other evangelists to get at Pat Robertson so that Bush could win the Republican nomination.

The end of American Energy Farming Systems marred the lowly native crop for the following decades, and only in recent memory has it regained any recognition as a potential food crop.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 47 page chapter, of (so far) a 310 page book with 135 sources, you can support our work a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content (Episode 151), the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can subscribe on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

https://www.americanantiquarian.org/proceedings/44817393.pdf

Amato, J. A. (1993). The Great Jerusalem Artichoke Circus the buying and selling of the rural American dream. University of Minnesota Press.

The Commission. (1981). The American artichoke: The weed that Whips Opec!

Farm chemurgic council. (1936). Proceedings of the second Dearborn Conference of Agriculture, Industry and Science, Dearborn, Michigan, May 12, 13, 14, 1936.

Hale, W. J. (1979). Prosperity beckons: Dawn of the alcohol era. Rutan Pub.

Windish, L. G. (1981). The soybean pioneers: Trailblazers, Crusaders, missionaries. L.G. Windish.

Kopf, K. (1963). Agricultural Diversification.

Prospectus for Energy Age Marketing and Management Corporation, Rapid City, South Dakota, n.d.

Fred Hendrickson, memo to James Dwire and the Christian Growers Association, January 11, 1982.

James Dwire's 1980 financial statement, found in company papers accumulated during McLeod County's investigation of AEFS

James Dwire, State of Minnesota v. Fred Hendrickson, vol. 4, 797.

Biggart, N. W. (2014). Charismatic capitalism direct selling organizations in America. University of Chicago Press.

Fred Hendrickson, "What's New at AEFS?" National Growers Convention, June 18, 1982.

Sam Newland, "Magnetic Preacher," Minneapolis Tribune, June 6, 1976

Investigator Dick Moisan observed during his report to McLeod County attorney Peter Kasal about an AEFS meeting in Montevideo, Minn., on September 28, 1982

AEFS's one-page Three Year Jerusalem Artichoke Crop Growing Agreement, in Hendrickson's papers

Mark Hughes, telephone interview by AEFS investigator Vincent Carraher, employed by Dwire's defense firm, Thompson and Lundquist, September 27, 1983, found in author's company records.

American Jurisprudence, 2d ed., vol. 18B (Rochester, N.Y.: The Lawyers Corporative Publishing Co., 1985), section 1689, 542, and section 1711, 566.

Tim Ribbens, audit for AEFS, March 18, 1983, Lyon County Court records.

Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Erickson, letter to AEFS, May 24, 1983, files of the Minnesota attorney general.

Steve Brandt, "Three Indicted on Swindling Charges in Jerusalem Artichoke Promotion," Minneapolis Tribune, October 31, 1984