The Legacy of Beach Plums: History, Cultivation, and Conservation

The fruit of the dunes

The beach plum, Prunus maritima, is one of several plums native to modern-day North America. The beach plum, however, is unique in that it grows in poor soil and has a high capacity for controlling erosion. The native beach plum is commonly found across the coasts of the northeastern United States but ranges from Newfoundland to North Carolina. Unsurprisingly, as a beach tree, it was one of the first New World plants the colonists saw when they came ashore in the 1600s but was documented even earlier by Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazano who referred to them as “damson trees” in 1524.1 While Indigenous groups across the coast harvested the fruit, there seems to be little evidence of management or documentation of processing from early settlers.

Arriving on the (now named) Hudson River, Henry Hudson described the shoreline as covered in beach plums. Unlike many native fruits, beach plum is known to have an extremely diverse set of genetics, causing significant differences in tree size, fruit size, flower size and color, and adaptability.2 In 1785, Humphrey Marshall described the plant as “The Seaside plumb” which sported numerous flowers but little fruit and was used as an ornamental when brought to Europe.3 In 1872, the American Agriculturalist noted “The fruit varies in different plants, not only in color and size, but in quality- some specimens being quite pleasant to the taste, and others harsh and acerb.”4

Despite this challenge, several attempts were made during the 19th and 20th centuries to develop beach plum cultivars with consistently good fruit qualities. As of 1900, only three cultivars were identified; ‘Bassett’, ‘Alpha’, and ‘Beta’, which have all since been lost.

Despite the work of the Soil Conservation Service, with folks like J. Milton Batchelor who scouted for high-quality varieties to bring into production, little progress was made initially, but the beginnings of change were present. This was driven largely by Liberty Hyde Bailey’s “The Cultivated Native Plums & Cherries,” which was the first real scientific work on these fruits (which also identified 140 cultivars of native plums), and following the Hatch Act, more than 70 bulletins were dedicated to the study of native plums and cherries. Researchers and breeders, primarily in the northern Great Plains, focused on collecting and identifying the best genetics for native plums, introducing over 100 varieties of native plums (not just beach plums) during this period.

Bailey led much of the research, spending considerable time at Jonathan Kerr’s orchard Eastern Shore Nurseries in Denton, Maryland, researching every variety he had in likely the most extensive trial on native plums in North America.5 Despite the hype by growers and breeders around all native plums, the challenge has historically been that the skins are astringent, despite the sweetness of the flesh inside.

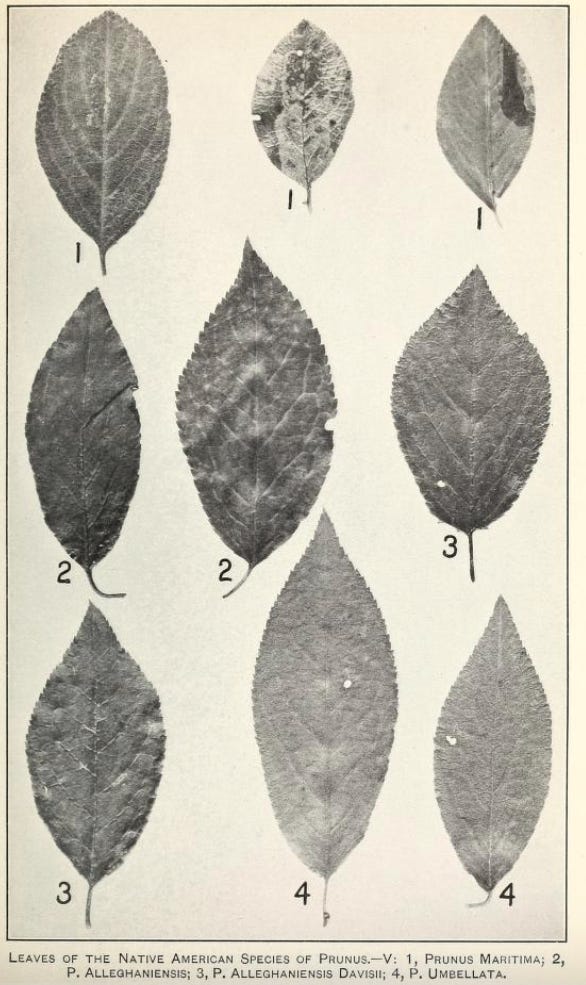

From all of the breeding work, by 1911 the following beach plums were named: ‘alleghaniensis davisii’ (described as native to the northern Alleghenies and southern New England with calyx lobes only slightly shorter than the tube), ‘umbellata injucunda’, ‘umbellata tarda’ (both umbellata coming from southern states), ‘gravesii’, and ‘maritima’.

Batchelor wasn’t the only researcher backed by the Soil Conservation Service; John Pennypacker was also sent to scour the East Coast, flying over dunes in 1913 to identify the beach plums while in bloom to collect genetics for future research. In his thesis at the University of Pennsylvania, he identified eight varieties of beach plum taken from across the northeast and mid-Atlantic.6

The native plum industry as a whole had hoped that the improvements of the railway, canning (which had caused the blueberry industry to explode), and interest in new fruits would help the plums grow to a staple across the nation, but instead, the American plums were largely used to develop thicker-skinned hybrids, which gave the disease resistance of the native plums to the European plums with less astringency.7 Luther Burbank led this charge, including the now-famous ‘Santa Rosa’ plum, which still dominates the industry.

Batchelor, mentioned just moments ago, was assigned by the Hillculture Division of the Soil Conservation Service to travel the North Atlantic coast area in the 1930s and found three named varieties— only one of which continues to exist today for sale. ‘Hancock’ was found in Forth Hancock, NJ with a blue fruit and early maturity. It’s believed to since have been lost, but various folks in forums have claimed to have it, so it may still exist today. ‘Safford’ was found on Plum Island, MA, with heavy bearing fruit, and “Premier”, also from Plum Island, MA, which had poor resistance to brown rot but the best selection of beach plum in terms of flavor.8

During this same time, Wilfred Wheeler also identified ‘Eastham’, out of Eastham, MA, which had tart fruit, good for canning, and small seeds, which are still in cultivation today. Wheeler had several other selections that have since been lost, including ‘Wheeler Selection No. 6’ from Truro, Mass with exceptionally sweet fruit, ‘Arrowhead’ a blue plum, ‘Snow’, a blue plum, and an annual bearer.

While these two folks were responsible for many selections at this time, other folks were busily identifying beach plums that merited further breeding. J.H. Putnam found one in Orleans, MA, ‘Putnam’, which he described as an “unusually large, promising, well-flavored beach plum.” The NJ Agricultural Experiment Station released ‘Raribank’, selected from the wild near Old Bridge, NJ which makes excellent jelly and is available to this day.

Into the 1940s, research continued, led by George Graves, a horticulturist who worked extensively with beach plum, alongside several other underappreciated plants (such as poison ivy).9 Graves also Managed the Massachusetts Agricultural Experiment Station, where he worked on developing better roadside plantings representing the diversity of the American landscape.10 He wasn’t alone in loudly advocating for the forgotten beach plum, however. The National Horticultural Magazine in 1944 stated that the beach plum’s “fruit flavor is unmatched by that of any other fruit known to the jellymaker or fruit preserver.”

At the time of his writing, the Arnold Arboretum and the University of Massachusetts collaborated with the intent of formalizing the development of a small fruit industry on Cape Cod. Cultivars were selected, diseases and pests were documented, and propagation was researched. Given the fact Cape Cod is largely a sandy mass, home to some of the largest rare pine barren ecosystems on the coast, its beachside landscape is often covered in wild beach plums, and finding selections that could grow in these otherwise inhospitable regions with consistently good fruit would revolutionize the wild beach plum industry in the region. For context, in 1841, 15,000 bushels of beach plums were harvested in only 3 Cape Cod counties.11

In 1949, James R. Jewett, a professor emeritus of Arabic at Harvard University and seasonal resident of Cape Cod, gave the Arnold Arboretum $5,000 to establish a fund to develop beach plums or other native fruit-bearing trees or shrubs. Two prizes, one for $100 and another for $50, would be awarded annually to the residents who had done the most to improve the potential of the beach plum. The first two prizes were awarded in 1941 to Cape Cod residents Mrs. Wilfred C. White & Mrs. Ina S. Snow. An art teacher by day, Mrs. White wasn’t just interested in the native plants of Martha’s Vineyard, but dedicated her free time to teaching Wampanoag kids to be proud of their history, offering free weekly pottery classes to those same kids.12,13

While Mrs. White was busy teaching, she also conducted experimental beach plum plantings and successfully petitioned the Massachusetts Legislature for funds for beach plum research to be conducted at Graves’s Agricultural Experiment Station and was allocated $500. Bertram Tomlinson, the Barnstable (Cape Cod) County Agricultural agent, alongside George Graves, were founding members of the Cape Cod Beach Plum Growers’ Association, which was officially formed on November 17th, 1948 to begin these experimental beach plum plantings.

The group started a Registry of Beach Plum Varieties to help drive development of the best-yielding plants, and frequently put out bulletins to highlight new findings around beach plums. Bulletin #11 appears to be the last bulletin put out, while John C. Hammond was president. Mr. Hammond is an interesting figure; while he was passionate about beach plums, he was invested in the cranberry industry and oyster production. Because of his closeness with oyster harvesting, he had very early on noted the warming climate as it impacted the oyster industry.14

With a knack for parsing out cause and effect, he also noted, regarding the beach plums, that:

The plums that grow on sandy land are sweet, mild and luscious— away from the beach— in swampy ground, in good pasture land, in scrub oak woods, in good soil in the perennial border, beach plums grow making a fine show of their feathering blooms, but in most cases when the bushes grow in fair to good soil the fruits are extra full of tannin content or pucker. They do not make as good jelly; in fact, some refuse to jell and the plums are not as good to eat out of hand as those from beach sands.

While yet to be proven, he believed that the source of tannin came from nearby oak leaf litter, and soils with high amounts of nutrients created poorer fruit, a comment supported anecdotally by beach plum growers. Dr. Tim Visel has clarified this, based on more contemporary research, pointing out that “I think that the substance or factor he (Mr. Hammond) was looking for included undigested leaf wax (paraffin) residues. That would explain the changing condition of wet terrestrial soils subjected to oak leaves in the presence of sulfur-reducing bacteria, and perhaps the declines he observed in beach plum yields over time.”15

The trials and experiments ultimately did not materialize, and the association declined. George Graves continued researching without the association, registering Beach Plum varieties in 1950. By this time, only a few beach plum varieties were named. One variant, coincidentally called the Graves Beach plum (named for Dr. Charles B Graves in 1897) existed, according to a New York Times article, only on one site in Groton, CT. As of 2000, the only extant wild population has since died.16

Pete Chrisbacher, a friend of the show, has researched extensively to identify what still currently exists, and the current list is inspiring. He notes 23 selections, listed below:

Premier (Historical selection having the highest field ratings out of all individuals examined on Plum Island, MA)

Hancock (Historical selection originating in Fort Hancock, N. J.)

Rutgers Jersey Gem (AKA Rutgers 1-1)

C.F. #5 (Cornell University / Dr. Richard Uva selection)

C.F. #134 (Cornell University / Dr. Richard Uva selection)

UConn 49 (CAES beach plum trials selection)

UConn 64 (CAES beach plum trials selection)

UConn 111 (CAES beach plum trials selection)

UConn 142 (CAES beach plum trials selection)

Worcester VT (Buzz Ferver selection from his old Worcester VT farmstead)

Jersey (Raintree origination?)

Ultramarine (grown primarily by Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops but was originally selected by John Meader who started seedlings supplied by the NH State Nursery)

Flava Island (Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops)

Yellow is Mellow (Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops)

Black Pearl (Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops Nana selection)

Blue Pearl (Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops Nana selection)

Multiverse (Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops Nana selection)

Double Rainbow (Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops) Prunus x maritima Ecos

Nana Line (seed-reproduced line from Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops)

Ecos Line (seed-reproduced line from Ken Asmus / Oikos Tree Crops)

Resigno Line (seed-reproduced Cape May NJ line from Mark Miller, Philadelphia PA)

Eastham (supposedly still exists, but not confirmed)

Squibnocket (supposedly still exists, not confirmed)

Today, despite the nearly two-dozen varieties documented, there are only four primary cultivars in production, ‘Eastham’, ‘Squibnocket’, ‘Hancock’, and ‘Raribank’. The rest will be found in specific nurseries here and there or through trading on forums. This speaks to how niche the fruit has remained and how long-term research has been lacking— but it has continued.

In the early 90s, the USDA SCS released a new variety of beach plum, ‘Ocean View’, which was field tested from North Carolina to Maine. The current location of these plants doesn’t seem to be public, and there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of it being sold to the public after the first official announcement.17

The early 2000s showed a rekindling of research, primarily out of Cornell, UMass, and New York. The UMass Cold Spring Orchard Research & Education Center grew 150 seedling plants from 14 collection sites in 2003.18 The Rhode Island Wild Plant Society released cultivation notes in 2001. Research out of Cornell University has been focused on identifying the best beach plums, with seeds collected and being grown out for the identification of improved genetics. As it stands today, based on Dr. Uva’s research at Cornell, the best beach plums can produce 4,000 pounds of fruit per acre, compared with blueberries at over 6,000 pounds per acre.19

In the spring of 2003, 210 beach plum seedlings were planted by Dr. Abigail Maynard (retired) at Lockwood Farm and 96 at the Valley Laboratory. These seedlings were raised at Cornell University from seeds collected from 35 sites from Maine to Delaware. The trees were evaluated annually. Growers have taken cuttings from select elite individuals to be propagated as possible cultivars in the future— noted in Pete’s list above.20

Richard Uva, the world’s foremost expert in beach plum, advocates for an orchard design that focuses on twelve-foot rows where the trees are planted five feet apart. Propagation can be done with seed, but this will produce different fruits, while stem cuttings, taken in the latter part of June, will propagate genetically identical trees. These cuttings should be between four and six inches in length, taken from non-fruiting branches. Root-inducing hormones are necessary for rooting of the cuttings, and like most cuttings, should be kept in humid, warm conditions.21 Alternatively, root cuttings can be successful as well— three to four-inch root cuttings taken in late fall can be placed horizontally in the soil outdoors and covered with straw.

The tree itself thrives in seaside conditions, growing in low-nutrient, high wind, unstable substrate, and high salt levels, as we’ve noted. They’re also excellent trees for erosion control, and dune stabilization and, alongside Eastern Prickly Pear, American Beachgrass, and Virginia Rose, can create an edible landscape in even the harshest conditions. All of these traits make the beach plum uniquely adapted for many of the challenges we face under climate change.

While we noted that beach plums don’t like nutrient-rich soils or extensive fertilizers, they will thrive and produce better crops with soils with some organic material and limited fertilizer, although not necessary for their survival. They’re also considered self-fertile but will set better fruit with cross-pollination. In the poorest soils, the beach plum will stay shrubby and rarely break ten feet, while improved soils have shown these shrubs to reach up to twenty feet.

One of the largest challenges, much like many tree crops, is consistent production; beach plums rarely produce year over year in similar volumes. Heavy fruit production in one year often leaves very little resources for flower production for the following year. Historically, this is managed with soil amendments, but given the beach plum’s disdain for soil amendments, this is unlikely to solve the issue.

What should be inspiring, however, is that the beach plum has quickly shown improvement from selections suggesting that new selections await, should we take the time to learn the trees.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 11-page chapter, of (so far) a 1310-page book with 989 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #238 of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Uva, R.H. 2003. Taming the wild beach plum. Arnoldia 62(4): 11-19.

W. F. Wight. 1915. Native American species of Prunus. Bulletin of the U.S. Department of Agriculture 179: 1–75.

Marshall, H. (1785). Arbustrum Americanum: The American Grove, Or, An Alphabetical Catalogue of Forest Trees and Shrubs, Natives of the American United States, Arranged According to the Linnaean System, p. 112. Joseph Crukshank, Philadelphia.

http://www.beachplum.cornell.edu/bpguide.pdf

Damery, J. (2018). Recalling plums from the wild. Arnoldia, 75(3), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.291551

Goff, E. S. 1891. The present status of native plum culture. Garden and Forest. 4 (193): 523–524.

Graves, George. “Looking Toward Beach Plum Cultivation.” Arnoldia, vol. 9, no. 11–12, 1949, pp. 53--64, https://doi.org/10.5962/p.249250.

Pennypacker, J. Y. (1919). Observations on the Beach Plum, a study in plant variation (thesis). Observations on the beach plum, a study in plant variation.

https://archive.org/stream/transactionsofm194344mass/transactionsofm194344mass_djvu.txt

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112019622213&seq=97

Bailey, J.S. (1944). The Beach Plum in Massachusetts. Massachusetts Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin Nc. 422:16 pp.

https://vineyardgazette.com/news/2024/09/05/closing-gay-head-school-still-reverberates-tribal-elders

https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/433405741/

https://www.bluecrab.info/forum/index.php?topic=74634.0

The Truth About the Cape Cod Nitrogen Problem – Habitat Cycles

Tim Visel, November 2011

https://saveplants.org/plant-profile/3646/Prunus-maritima-var.-gravesii/Graves-Beach-Plum/

https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/caes/documents/plant_science_day/2021/caes-plant-science-day-program-2021.pdf

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/plantmaterials/njpmcrb12123.pdf

https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19450302100

Sonia G. Schloemann, “Beach Plum Seedling Evaluation Trial”, Department of Plant, Soil, & Insect Sciences, University of Massachusetts, 2005

Slideshow from Cornell Extension, Richard Uva “Beach Plum - New Developments”