Examining the Confluence of Farming and Economics at Wharton through the Land Value Tax

The Study of Economics and Land Value Tax

This piece is a contribution piece from one of the researchers at the Poor Proles Almanac who has chosen to remain nameless.

As Andy and co. took us through the PPA series revealing the origins of the permanent agriculture movement, we uncovered the Wharton School of Economics at the University of Pennsylvania as a gathering place for some of the era's most brilliant minds: Rexford Tugwell, J. R. Smith, and Scott Nearing. Despite their backgrounds in economics, all three were drawn to farming, horticulture, botany, and the land for diverse reasons. However, Simon Patten was Absent from those episodes (but mentioned in the substack!). Patten held the distinction of being the first economics professor at Wharton, starting his tenure in 1887. By 1896, he had become the department chair, and under his watch, Wharton became a respected institution. His leadership came to an end in 1917, when (like Nearing) his contract was not renewed due to his progressive activism.

This chronology reveals that Nearing, Smith, and Tugwell all worked under Patten during their time at Wharton, with Nearing even serving as a doctoral student of Patten's. Before joining Wharton, Patten himself had been a student of the German political economist Johann Conrad, who, like Patten, had transitioned from farming to economics. Conrad's other notable doctoral students included Richard T. Ely, who played a prominent role in the Progressive movement and founded Lambda Alpha International, an organization dedicated to promoting the study of Land Economics in universities. With Patten at the helm of the economics department at Wharton, it's no surprise these individuals gravitated there, at the intersection of farming and economics. The common thread among them all is the study of how land influences economies.

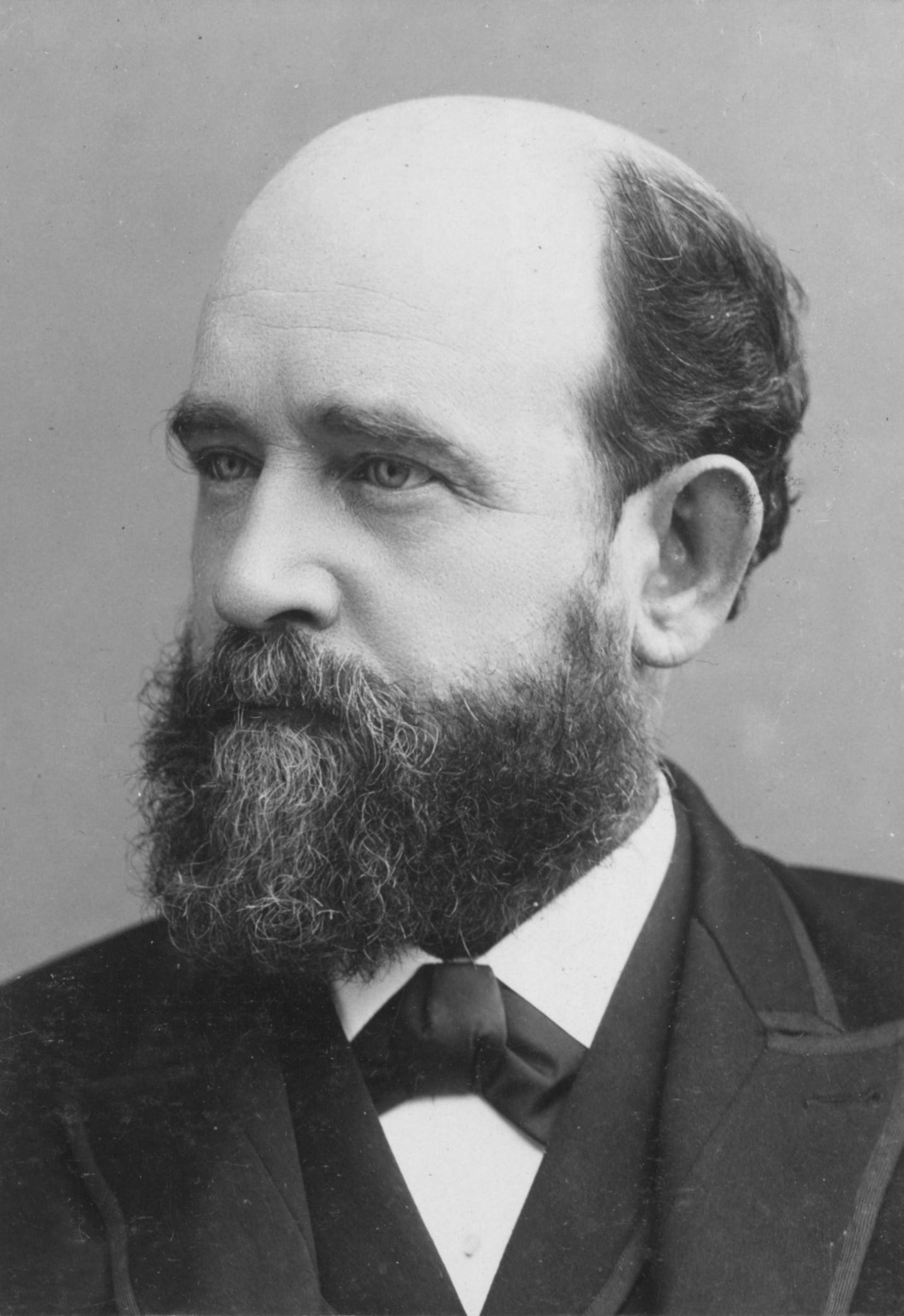

At the beginning of the first Nearing episode, we learn of his residence in Arden, a Delaware village known as a "Single Tax Community". The founders of Arden combined elements of political and economic philosophy found in the works of Anarcho-Communist, Peter Kropotkin, the Socialist textile artist William Morris, and most of all, the writings of Political Economist Henry George. Nearing's exposure to the work of Henry George can likely be traced back to Simon Patten, whose own economic theories echo elements of Georgism. In this article, we'll explore the principles of Georgism, delve into its historical context, and consider its contemporary relevance, particularly in addressing the challenges within agriculture today.

On Liberalism and Georgism

Georgism, alternatively known as Geoism, or the Single Tax, is a school of thought that picks up the often-ignored thread of social progressivism and subtle radicalism within classical Liberalism. Henry George’s work Progress And Poverty was written in 1879, and is credited with kicking off the Progressive Era in American history; a backlash to the growing inequality and obvious corruption of the so-called Gilded Age, where barons of industry lived with extreme wealth, society’s productive capabilities due to the process of industrialization skyrocketed, and yet want and poverty grew in proportion to the increase in wealth produced by society as a whole (a phenomenon which none of us are familiar with and is unthinkable these days).

George believed that Capitalism would invariably lead to this end. But unlike many in the labor movement, he did not see the fundamental conflict in modern economics as being between Labor and Capital. Instead, he argued that the true conflict lay between the productive forces of Labor and Capital combined and landowners who profit from the value created by these forces through rent and real estate speculation without contributing anything to the process.

It is important to remember here that classical Liberalism was a movement against the aristocracy and monopoly privilege granted by kings to lords and a handful of merchants. The fundamental legal privilege that defined Feudal society was land ownership. From 1066 onwards in England, and then Europe, the trend was one where common lands and common resources became privatized and commodified. Where once there were rules in place to protect commoners’ access to forests, fields, and water (see the Charter of The Forest), these were replaced as fences went up and peasants were forcibly removed from lands and forced into cities in a process called enclosure. Where once vacant land meant the opportunity to plant seeds, build a house, or hunt and forage, it now meant doing those things was a crime.

The idea we now call “Liberalism” is associated with the status quo. This has been further reinforced by the inappropriately named doctrine of “Neoliberalism” pushed by Thatcher and Reagan, and those politicians who came after them who passed free trade agreements in the name of looting foreign countries of resources for their rich friends while gutting their domestic economies. But at the time in which Liberalism was originally developed, it was often a loaded gun pointed at the kings, the lords, and, frequently at the destruction of the commons. There is a tendency now to think of Liberalism as the philosophy that justified all this; that it encouraged privatization, forced peasants off their ancestral land, and turned them into proletarians, people dispossessed with only their time to sell to a capitalist in exchange for meager wages.

And this is partially true - a major factor of Enclosure was the desire for increased productivity due to expanding markets in things like wool. But a major tendency of Liberal philosophy at the time saw the private ownership of land as the foundation of these problems, and viewed it as a power to be restrained, much like the State. It should be fairly obvious that the thinkers who propose ideas are not necessarily the ones implementing them, and the implementation of a philosophy often bears little resemblance to the theory. Because of this, Henry George, like some before him and many after him, saw that despite the political revolutions in America, France, and elsewhere, the economic promises of liberalism fell short.

What good is the right to vote for a starving public? Freeing markets from misguided mercantilist philosophy did create wealth previously unseen in society, but something else was happening at the same time which prevented average people from improving their lot, regardless of how hard they worked. George picked up the thread where many before him left off - it was private land ownership.

Land Reform

In most periods of radical social upheaval, land reform is at the top of the list of demands. Unsurprisingly land reform has taken many shapes, from the land redistribution of Ancient Rome undertaken by Tiberius and Gaius Graccus to the Diggers in 1649, to the Irish Land Acts of the late 1800s, to the enshrining of the Ejido system in the Mexican constitution of 1917. All of these are attempts to combat what seems like an inevitable occurrence wherever the law allows for private property in land; the concentration of land in a few hands. When the land is owned by a few, those few people essentially control the ability of the many to live.

Many of these attempts at land reform have been successful in distributing land more democratically but often come with a high cost in blood, as well as frequently a high cost in productivity, leading to periods of food insecurity and high prices. In many cases, their success waned after a few decades. George believed that there was a simple way to democratize land access while also spurring economic productivity, and hopefully, avoiding bloodshed in the process. This solution is simply to place the burden of taxation entirely on land values, while still allowing private use of land, with decision-making power over what happens with that land left to private individuals as it currently is. As mentioned before, this was not an original idea of George’s but his writing was the most eloquent and fully-developed defense of this idea. Early proponents of this tax included Adam Smith, John Locke, Ben Franklin, Thomas Paine, J.S. Mill, and even some large landowners who - aristocratic title or not - constituted the class of landed gentry, and found the case for taxing land so compelling that they supported it.

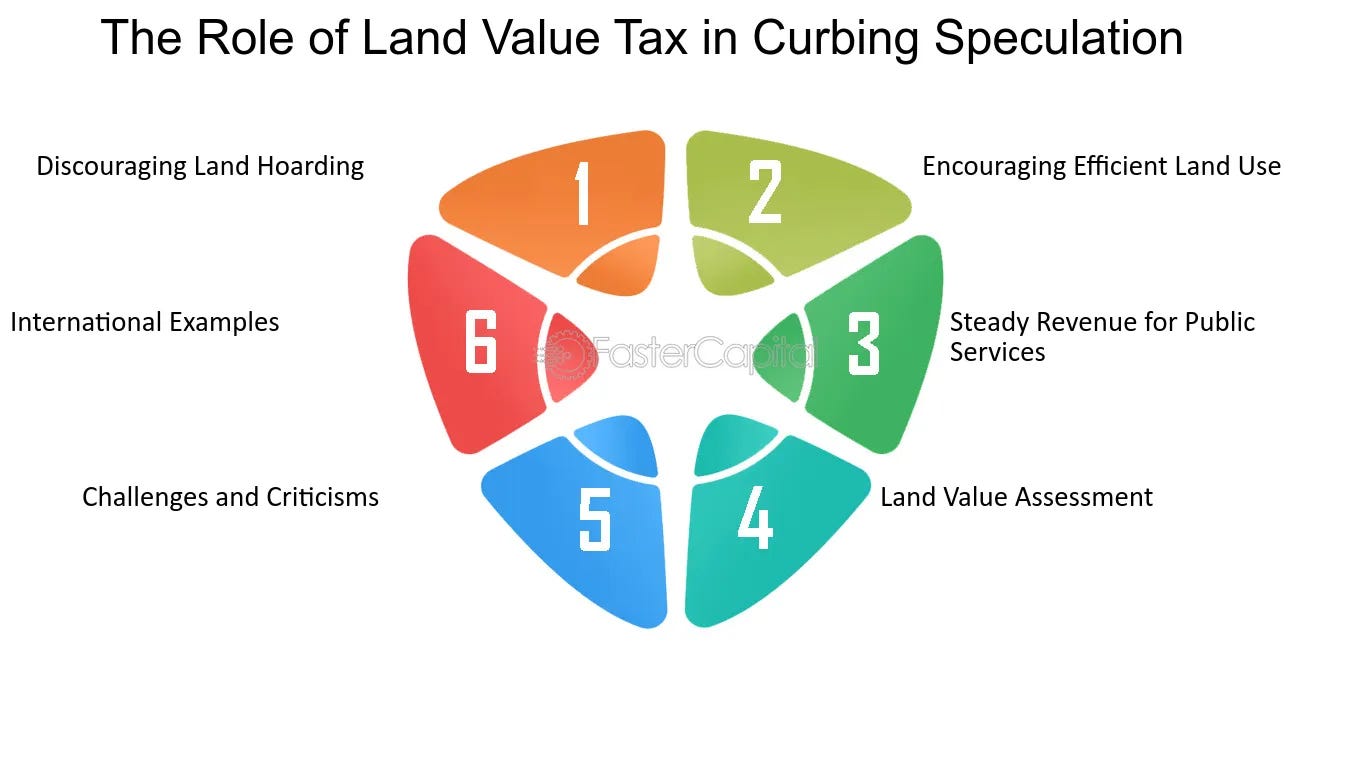

How Land Value Taxation Works

When we talk about "land value," we need to clarify what is and isn't included in that definition. Land value is the dollar amount that a parcel of land commands due to its inherent qualities, independent of any improvements made to or on the property. Inherent qualities of land include factors like its fertility, mineral deposits beneath it, and most importantly, its location. As all real estate brokers know, “location, location, location” is the cardinal rule of real estate. This is why a square meter of space in a vacant lot in Manhattan can cost more than many acres of land in Iowa. These inherent qualities translate into land value through simple demand. Fertile land, such as in the Midwest, is more desirable for farming, driving prices up due to competition among farmers. Conversely, rural land in areas like the Southwest, where farming is less feasible, will have lower prices. Historical examples include the spikes in land values when gold was discovered in California and oil in Texas, as people rushed to mine these resources. In cities, where most people work, the high demand for living space near jobs drives up land values. Essentially, land value is determined by how many people want to be in a specific area. The more people there are wanting access to space, the more valuable the land is.

Land values are derived from the total social and economic activity in an area. Public investments in infrastructure and the presence of amenities like good schools, roads, restaurants, clubs, or theaters drive up land values, reflecting the desirability of the area. Land value does not include buildings, fences, or other improvements added by humans. These contribute to property values but are separate from land value. What we call “property value" combines land value and improvement value, and this combined figure is currently the basis for property taxes. A certain percentage of this figure is taxed according to different mill rates, which represent the dollar amount taxed per $1,000 of property value.

To illustrate, consider a new house on a one-acre lot next to a one-acre vacant lot. Under the current tax scheme, the property with the new house pays much more in taxes than the owner of the vacant lot. However, under a Land Value Tax (LVT) scheme, the owners of both properties would pay the same amount. This means the person who builds and improves is not penalized (as they are currently), while the holding cost for the person who does nothing with the land should be high enough to discourage such inactivity. If the area becomes more popular, the land values of both properties will increase equally, and their taxes will rise accordingly. Each owner can decide how to use their land, but logically, it becomes more advantageous to develop or at least use the land, or sell it to someone who will, rather than pay a high fee while it does nothing for anyone.

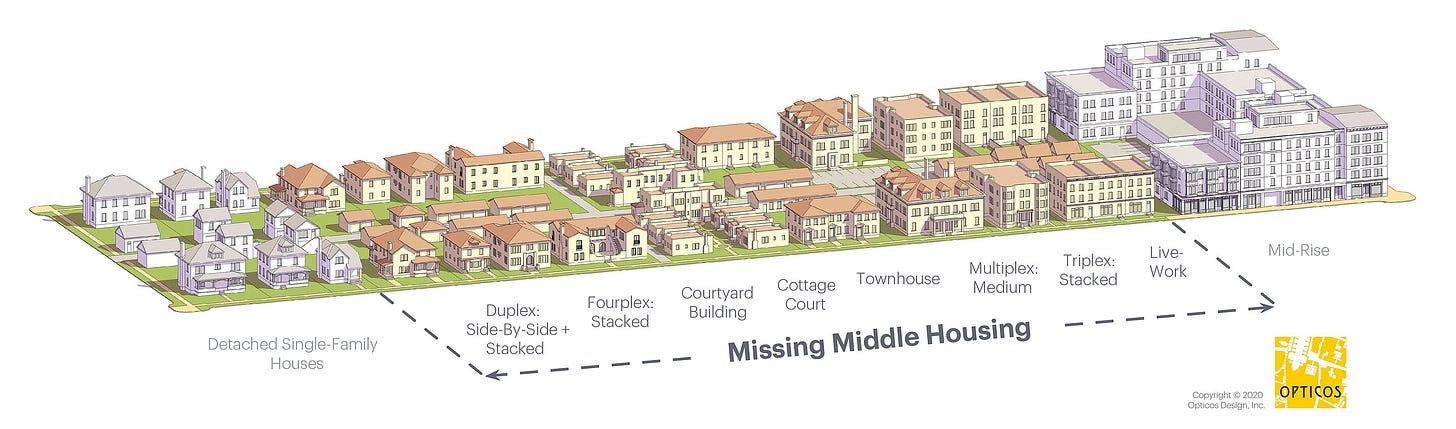

When LVT is fully implemented (taxing 100% of the land’s value), it eliminates the incentive to hold land idle or underutilized in anticipation of future price increases, thereby reducing speculation and making land more readily available for productive use. Because productive use of land becomes the only way to make a profit, ownership of land conveys no economic advantage whatsoever. While not all land needs to be used commercially (after all, we will all need homes to live in and not all of us are interested in our homes doubling as commercial spaces) in areas with high demand, it becomes more profitable for developers to build denser housing rather than single-family homes in city centers. Thus, the intensity of land use aligns with the demand for that land. If demand is very high, such as in a downtown area, land use must be very efficient. Buildings will likely become taller, taking up a smaller footprint and providing more shops or homes in that space. Where demand is lower, properties can be larger since land values will be lower, and people will be more able to afford the holding fee. However, in both cases, speculation cannot occur, which means the patchwork of vacant lots and derelict buildings alongside fancy hotels or storefronts that we see today would not exist.

By using land values as the basis for taxation, we can reinvest the money generated by everyone's labor back into the community. Under the right conditions, this can create a feedback loop where public investments can even raise land values by more than the value of the investment itself (Henry George Theorem), which are then collected once again, and reinvested. This constant incentive to use land as productively as possible maintains a competitive housing market and drives rents down, allowing newcomers to join the community.

Conversely, not taxing land values allows landowners to pocket this money, creating the opposite feedback loop. Desirable areas become more expensive and less accessible to new buyers and renters. As demand increases but access remains limited, landowners profit more, leading to an affordable housing crisis, economic stagnation, and business decline.

Why are land values so special?

All productive activity in an economy relies on labor, capital goods, and natural resources. We use labor and products made by people (capital) to interact with the natural world or with goods ultimately derived from it. For farmers, this means combining human labor with tools and equipment like tractors, fertilizers, and trucks, along with natural resources like land and water. Unlike labor and capital, which are produced by humans and can be increased to meet demand, land has an inelastic supply. We cannot create more land or control natural phenomena like rain. In markets for labor and capital goods, new entrants can compete because there is no limit to the amount of capital that can exist, and labor can be redirected as needed.

This creates opportunities for innovation and growth. However, land and other natural resources are finite. Those who own them hold a piece of a pie that cannot grow. Instead, the value extracted from these resources depends on how much others need them. This makes land ownership unique; it is a zero-sum game, unlike the markets for labor and capital. Since land is essential for life and production, landowners possess a monopolistic good with high demand, independent of their effort or skill. By treating land as just another form of capital, we allow landowners to determine when and at what price others can access this fundamental resource.

Unlike capital, which depreciates with use, and labor, which requires continuous effort to yield returns, land appreciates passively due to its fixed supply and increasing demand as populations grow. Short-term gains from labor or capital often end up benefiting landowners in the long run, making land a logical source of tax revenue. As average wages rise, so do rents. Technological advancements that increase worker productivity typically do not benefit the workers or even business owners for long, as landowners raise rents accordingly (if the business owners own the land as well, they will benefit doubly from the increased efficiency). The inelastic supply of land gives landowners the leverage to capture the gains made by productive society, leaving others on an economic treadmill. This is why owning a piece of land is a key part of "the American Dream"—it represents a way to escape this cycle. Unfortunately, to escape the cycle is to participate in intensifying the problem.

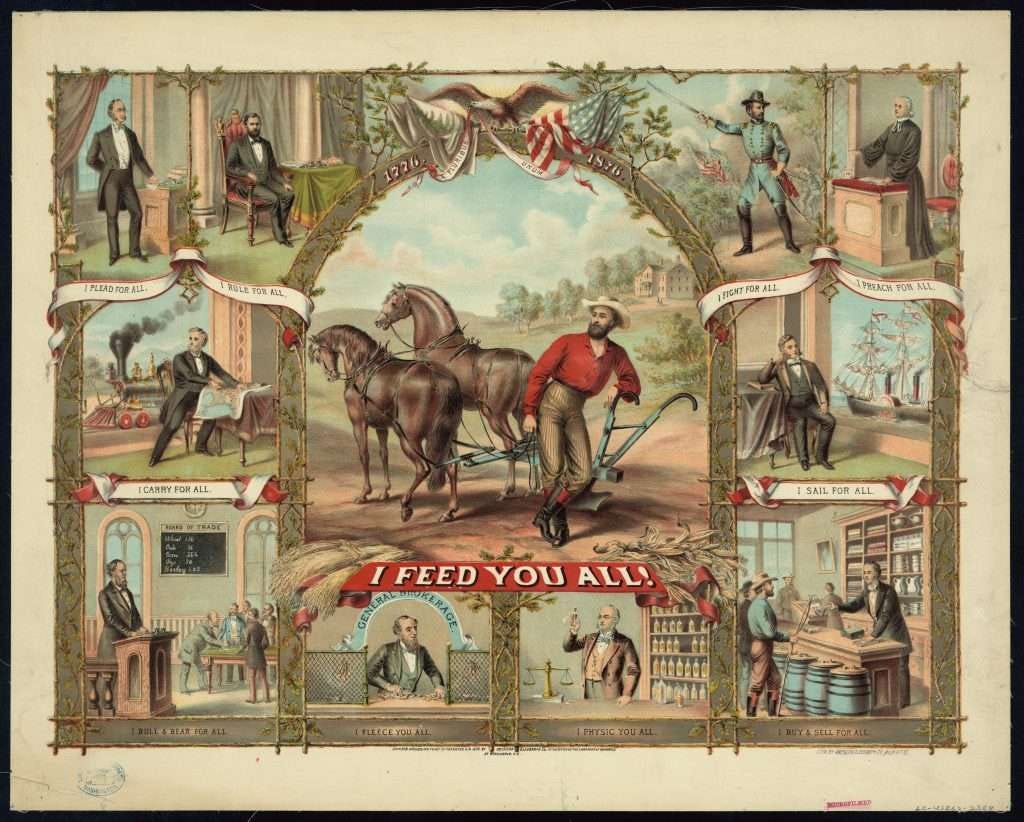

Capitalists must seize every profitable opportunity or lose out to rivals, while disruptions like strikes and idle capital mean wasted resources and lost profits. Workers, on the other hand, scramble for job openings, driving wages down in a desperate race to the bottom. Strikes or lockouts likewise test their endurance, even with strong mutual aid networks. Both groups, dependent on access to land to exist, suffer in this war of attrition.

Meanwhile, the landowner watches from the sidelines, unaffected by their struggles. The landowner’s wealth grows even as their land sits idle, its value increasing simply because others need it. The more land they withhold, the more valuable it becomes. While workers and capitalists battle for survival, the landowner grows richer, profiting from the deprivation they impose on society. The landowner thrives on this struggle, making money not by contributing, but by denying others the essential space they need to do the work that keeps society afloat.

Won’t Landlords Just Pass On The Tax To Renters?

Ultimately, the price of a good or service is not determined by what a producer wants people to pay for it, but what people are willing to pay for it. In most markets, when customers decide to buy less of something or shop elsewhere due to an increase in cost (such as higher taxes), the company makes less of that thing to account for the difference, and the company can still produce it profitably. However, due to land’s inelasticity, landowners cannot simply make less land to reduce their costs and make up for lost tenants. At a certain point, they must accept what tenants are willing to pay, or face vacancies.

If this happens now, it may not be the end of the world for the landowner, since the land is increasing in value even if the owner is not collecting rent. But when that value is taxed away, the landlord has every reason to fill those vacancies as soon as possible, or else they will simply hemorrhage money. Accepting what renters will give and paying the tax is the only option besides selling the property. The only way to make a profit without ultimately raising one’s taxes at the same time is to improve the property.

In the country, this plays out similarly. A profit could only really be made if a landowner chooses to manage their land to court tenant farmers. If a landowner builds fencing, greenhouses, invests in irrigation, or includes the use of tractors and equipment in the lease agreement, these are potential sources of profit. If a landowner wants to simply rent out a field for the tenant to make all the investments for themselves, the landowner will be better off selling the land.

What Does All That Mean For Farming?

For decades, the average age of the American farmer has been increasing. Young people born into farming families often find work off the farm, and the barriers to entry for people who want to farm are so high that not many can afford to break into the industry without a family connection. With events like the war in Ukraine that led to skyrocketing prices for fertilizer, and sent major shock waves throughout international agricultural markets, the margins that farmers can expect are as thin as they can be. The amount of risk in farming is high and the payoff for most commodity crops is small enough to leave many farmers in a position of annual precarity; Taking on debt to pay for seed, fuel, machinery, and labor, and on top of that having to hope that the increasingly unpredictable climate does not lead to a drought, or flood, or some other crop-killing catastrophe.

All of these, plus the legacy of “get big or get out” have led to severe consolidation in American agriculture. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack said in an interview with Axios that “the vast majority” of farm revenue last year went to “the top seven and a half percent of farms” and expressed deep concern about small and mid-sized farmers being crushed by “consolidation of farmland in farm profit”.1 His identification of farmland as a part of farm profit is key. This top seven and a half percent of farms are not amazingly productive businesses that simply outcompete the other farmers. They just hold vast amounts of very valuable land.

It has been said that farming is a “live poor, die rich” life. Farming is hard work, financially risky, and there is often little if any reward year-to-year, but when a farmer sells the farm, they make a lifetime’s worth of profits at once. For all the previously mentioned reasons, purchasing additional land is often a safer investment compared to acquiring more capital or increasing labor inputs in your existing operation, which entails ongoing costs and risks. While land may not always offer the fastest returns, it's a reliable, low-risk option that doesn't require active management to generate profits. This makes it an attractive choice when compared to diversifying a farm or intensifying operations. It's crucial to distinguish between the farmer here as the land owner and the farmer as the land user. One resembles a land speculator, while the other bears the responsibility of feeding us.

Scottish farmer and doctor of Animal Science, Dr. Duncan Pickard puts it thusly in his book ‘Lie of The Land’:

Because taxation favors the property owner over the wage earner, personal wealth is increased more securely by maximizing the amount of land owned. This means that a large owner-occupier sees his route to increasing wealth not by cooperating with his neighbor, but by fostering the strategies of predators: waiting for some misfortune (or financial downturn) which might enable the larger to swallow the smaller.2

Even in a situation where a farmer who owns their land outright has no desire to sell or rent that land, the advantage conferred to them by simply not having the monthly cost of rent or a mortgage is massive, and ultimately produces a situation that benefits those who have the money to buy over those who may be the better farmers.

Hamlin Garland, the American Georgist and author who wrote about the plight of poor farmers in the late 1800s wrote into his short story ‘Under The Lion’s Paw’ a character who exemplified this very dynamic. Jim Butler “earned all he got” by hard work, until “a change came over him at the end of the second year [of farming], when he sold a lot of land for four times what he paid for it. From that time forward he believed in land speculation as the surest way of getting rich”.3 Butler then stopped being a farmer as a user of land, and became only a farmer in name, as a person who owned the land on which others farmed. Much of America’s farmland is owned by farmers of this sort, who are either engaged in speculation while still cropping to earn an often meager income, or simply renting their land to others.

In the US, about 40% of agricultural land is currently rented.4 Of that 40%, the vast majority is owned by ‘non-operator landlords’. In other words, people or companies who are not farmers themselves. In cities, landlords tend to provide (to varying degrees) some services which we might call “property management”. Owners of farmland who then rent it to farmers do not, in general, provide a service. They merely allow a farmer who works for a living to access a piece of land on which they can labor, in exchange for a piece of the value created by that farmer.

This duality of land as both a speculative investment - and therefore valuable to own even if it is not being “put to work” - and a necessity for farming is what is leading to the consolidation of farmland into fewer hands, and what is keeping new farmers out of the market (and causing the housing shortage that we are witnessing in towns and cities). Because land possesses both of these qualities, there is no other outcome than the inevitable one that we are currently witnessing. Land values increase for a myriad of reasons, driving more demand for land as an investment, which drives land values up further, which ends up making land prohibitively expensive for newcomers. The same reason that those farmers who currently own land are holding onto something valuable is ultimately the thing that is causing many of the problems we see in agriculture.

Smart policy for agriculture would encourage competition, promote innovation and efficiency, and allow farmers a greater reward for raising food. Land Value Taxation does all of these things when it replaces other taxes that put downward pressure on production. It offers a greater reward to farmers than they are currently offered, but that reward comes from farming itself; for innovative techniques to increase yield and economic value, for making less land go farther, for making more efficient use of water, for diversifying their crops and finding higher value crops than the corn and soy which are only worth growing because of subsidies, for putting more capital to use and for hiring more labor. What it does not reward farmers and agribusiness for is simply owning the resource that all other farmers need, and being able to reap a greater and greater reward the more desperate other farmers get. In short, the potential reward is much higher for land users than they currently enjoy, but lower for land owners.

On Agricultural Efficiency

Between the Back to the Land movement in the 60s and 70s and the new 21st-century iteration of the same movement, there have been dozens of competing philosophies of food production which all place themselves in opposition to “conventional agriculture”. Conventional Ag is a thing that is a bit hard to define and often serves as a boogieman for all that is bad about farming, depending on who is talking. It can be broadly categorized though, as being land-extensive; it generally relies on few, often subsidized crops in a highly streamlined system that favors scale and simplicity over labor and complexity. Simple systems are easy to mechanize, and mechanized systems are easy to scale. Thus, we have tens of millions of acres of corn and soy monocultures grown across North America. These crops are grown incredibly efficiently by a very small subset of the American population.

Though the modern farming philosophies that place themselves in opposition to Conventional Agriculture are all distinct, they also all share some things in common. Whether the farm calls itself organic, permaculture, no-till, regenerative, holistic, or something else, these approaches can all be characterized as being labor or capital-intensive. Compared to conventional farming, these are all systems that tend to be more complex, more diverse and require more labor to manage. These systems are often harder to scale and mechanize because of this complexity, but when done well, can offer increased output while being less dependent on finite and costly resources such as land, synthetic fertilizers, and fuels.

To provide a few examples of this, a labor and capital-intensive approach might look like daily paddock rotations for cattle or sheep, using specialized electric netting, or a grid system of more expensive permanent fencing compared to an open field with just a perimeter fence. The mental labor involved in managing each day’s grazing, observing field conditions, and making quick changes, and the physical labor of moving the animals is greater than in an extensive grazing situation, where animals are simply turned out onto rangeland and collected when they are ready for market. Proponents argue that when done correctly, this extra labor translates into more productive pastures, and therefore more future food for animals and potentially increased stocking densities.

Similarly, a vegetable farmer might decide to invest in high tunnels and trellising systems to lengthen their growing season and give crops protection from the elements, allowing them to grow specialized greenhouse varieties of high-value vegetables which would net them more profit than their field-grown equivalents.

Another example might be a native agroforestry system that mixes, say, a pecan or hazel orchard with row crops of grain. This double-enterprise would require careful economic planning to account for the time between the short-term yields of annuals and the long-term yields of the perennials. It may require two specialized harvesting machines rather than one. However, many farmers who already employ systems like this say that the combined income from mixed systems like this is worth the increased labor and investments. They may not get 100% of the potential yields on their annuals, and they may not get 100% of the potential yields on their perennials, but combined, they make more income than by trying to maximize either the annuals or perennials by themselves.

Despite the increased interest in alternative farming methods, none of these approaches have managed to shift the American food system away from the conventional structure. Though sometimes these small farms are genuinely able to produce quantities of food and revenue per acre that would seem incredible to commodity crop farmers given the space that these farms are working on, they have a hard time breaking out of niche markets. Some people will foolishly point to this as a sign of success, arguing that these methods are “resisting co-optation by big agribusiness”, and say that they are by nature closer to The People. The inability to scale up and make up more of the market share is mistaken for moral purity, and the small farm movement gets to remain the righteous underdog. It is worth asking then, which people are benefiting from this?

Small farmers trying to farm in these ways usually find out soon enough that to survive as a business without the benefits of scale and mechanization that larger farms have, they must almost exclusively sell to wealthy customers at farmer’s markets or to nice restaurants rather than at the grocery stores where most people shop. The customer base is small, and demanding, and the labor involved in reaching these customers is high. Through little fault of their own, since large acreage and mechanization are simply out of reach for these new farmers, these farmers hit ceilings that limit their ability to compete in the market with the bigger players. On the other hand, the large farmers are constantly walking on a knife’s edge. They neither have the leverage to haggle when they buy their necessities for the year nor do they have the ability to set the prices for their product at the end of the year - a luxury that the small farms that sell directly to consumers do have. The only ones who are winning are those who are making money off something other than production.

When acquiring lots of land is the norm, methods will arise that enable a farmer to farm on all that land. Economist Mason Gaffney who studies land economics, points out that:

[a]s market forces tend to foster ‘appropriate technology’, meaning that as land becomes dear [expensive], and labor cheap, technology bends in the direction of using more labor and less land. However, modern tax biases have brought the specter back in full force, because the tax code is now loaded with biases that favor the use of capital and penalize the use of labor, thus trumping market forces that would do the opposite.5

This means that in addition to the fact that commodity land contains the inherent trend toward consolidation, our system of taxation further incentivizes the employment of capital over the employment of labor. Within a complex web of tax laws, business owners have access to numerous techniques and tricks to save themselves money on their purchases and avoid paying taxes on their assets, but hiring labor comes with heavy costs, and workers themselves seldom have the luxury to use these same tricks to save themselves money during tax season. It is no surprise then, that our farms are mostly seas of monocrops, often tended to by just a few people using machinery that does the work of hundreds of workers.

Anyone who has done farm work can tell you that having a machine that helps you accomplish a task is a great relief. Certainly, mechanization should not be seen as a bad thing, as denying ourselves technology would simply make our own lives much harder and the results of our labor far less fruitful. Likewise, economies of scale have genuine value and should not be avoided simply because of some idealized vision of what farming used to be. However, if tax biases favor overinvestment in capital at the expense of labor, this can have some distortionary effects. It can lead to potentially misleading results when it comes to measuring our agricultural productivity.

Dr. Pickard explains, “Another myth that needs to be exposed is the widespread belief that large farms are more efficient than small ones. And we are often told that UK farmers are the most efficient in Europe. These ‘facts’ need to be questioned, because the terms in which efficiency is described are never defined. The only measures of efficiency that support these claims are those of output per farm or person employed in agriculture. It is therefore obvious that because the average farm size is the highest in Europe, UK farms are the most efficient. What about other measures of efficiency such as output per unit area farmed, or per unit of fossil energy used, or per unit of capital employed? Why does no one compare other indices of efficiency?”6 The Odums raised this question nearly a half-century ago, and yet little response has been made.

It may seem obvious that by defining “efficiency” differently, we will be led to conclude that radically different practices can be considered efficient, even when they are in direct opposition to one another. Where American agriculture shines is in labor efficiency. Like UK farmers, American farmers also produce extraordinary amounts of food per farm and per person employed in agriculture. But as we know, to undo the trend of farmers aging out of the industry, we will need a large influx of new farmers. If we were able to wave a wand and magically create a mass of new, young farmers, it stands to reason that the yield per person employed in agriculture would decrease simply by there being more people counted. This would give us the impression of decreasing efficiency, while also succeeding in the goal of providing new jobs in the industry. If these two things seem at odds with each other, perhaps other measurements of efficiency can provide better insight.

Economist Polly Cleveland sums up the findings of a 1985 study by two other economists, Yujiro Hayami and Vernon Ruttan, in her article entitled ‘Sustainability Squared’. “In the developed world” she explains, “farms in densely populated countries produced far more per acre, and far less per worker. Farms in Taiwan averaged about 16 times the output per acre of U.S. farms, using about 23 times as much labor. Closer to home, farms in the Netherlands produced about twelve times as much per acre as U.S. farms, using about two and a half times as much labor.”7

Measuring productivity by yield per acre, we see that there is a positive relationship between the amount of labor, and yield. So while yield per farmworker may decrease with an influx of farmworkers, all other things remaining the same, we are likely to see land being worked more intensively, and producing much more output per acre. If we were to use the Dutch example as any indication, it could be possible to double the number of jobs in agriculture while also more than doubling our productivity in yields, without bringing any new land into production at all.

To sum this up, yield is positively correlated with labor, while labor is negatively correlated with farm size. Our current taxation scheme incentivizes larger farms, which, although productive per farmworker, are quite unproductive by yield per acre compared to countries with a higher percentage of people employed in farming. Our tax system’s biases encourage underproductivity and suppress demand for labor.

Taxing land values can reverse this trend by discouraging excessive land acquisitions and increasing demand for labor and capital. This would make investment in labor and capital the more cost-effective option for generating profits. Lower land prices would enable farm workers to overcome the single largest barrier to becoming farm owners, fostering upward mobility based on one’s skills as a farmer rather than the ability to buy land. Those new farmers, in turn, would drive demand for more farm labor. Furthermore, funding Social Security and Medicare with land taxes instead of payroll taxes would reduce a huge source of downward pressure on labor demand.

While only a small percentage of people in the US aspire to work in agriculture, creating incentives for farmers to invest more in labor and capital can establish a new equilibrium. Increased demand for labor could attract more people to farm work and would even raise wages for migrant laborers. By removing biases that favor land and capital over labor, farm work could become a more profitable and attractive career, similar to the trades, offering decent wages and prospects for upward mobility and career advancement. A new balance between technology and human labor would emerge, using appropriate technology to support rather than replace labor. This equilibrium would reflect people's genuine desires to work on farms and provide affordable opportunities to live in rural areas with access to nearby jobs, without the built-in obstacles that they face now. And all of this would be possible without the paternalism and heavy state control of industry proposed by some agricultural reformers of the past such as Sir Daniel Hall in England or Rexford Tugwell in the States.

Fine, but farmers still have to own lots of land. Won’t this bankrupt them?

When the topic of taxing a farmer's land is raised, a common misconception arises. Many assume that because farming often involves extensive land holdings, such a tax would jeopardize the farmer's livelihood. However, this misconception stems from a misunderstanding of Land Value Tax. LVT is not based on land acreage but rather on land value. As mentioned before, land values primarily hinge on the desirability of a location for residential purposes, and farmland typically exists in rural areas with lower population density.8 While farmers may own significant acreage, their land often possesses relatively low rental value. Consequently, the tax burden per unit of land area tends to be considerably lower for farmers and rural residents compared to the average person.

Another erroneous assumption held by many is that a land value tax would promote extensive development, compelling landowners of pristine wilderness and farmland to replace it with skyscrapers. This notion is misguided, as there is no practical demand for skyscrapers in a forest or field of soybeans. The core idea is not to transform remote areas into urban centers but rather to ensure that each piece of land realizes its fullest potential before considering development elsewhere.

To get an idea of how rural land values stack up against urban land values, let’s take a moment to compare. According to the World Bank, agricultural land in the US accounted for 44.36% of total land in 2018.9 Depending on sources, America’s urban land only accounts for somewhere between 3% and 4% of the total land of the contiguous states, yet is home to about 80% of the population. Economists David Albouy and Minchul Shin of the University of Illinois and Gabriel Ehrlich of the University of Michigan conducted a study that tracked urban land values between 2005 and 2010, containing data from 69,000 land sales. Using this data, they estimated the total value of urban land in America at around 25 trillion dollars, which averages out to about $511,000 per acre. Nearly half of that 25 trillion was contained within just five cities - New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, and Washington D.C.10

By comparison, the average cost of an acre of farmland in 2010 including improvements (buildings, fences, and so on), which are never factored into the calculations for LVT, was just $2,140. Though dated, the 1994 USDA publication entitled ‘Taxing Farmland In The United States’ puts it plainly that, “The $5.1 billion worth of taxes on agricultural land reported by AELOS amounts to less than 5 percent of U.S. real property taxes.”11

As we can see, the land subject to taxation under LVT would not disproportionately affect farmers despite their need for large tracts of land. In the majority of cases, farmers are likely to see a decrease in the real taxes they pay, as their houses, outbuildings, sheds, silos, fences, tractors, and all of the other property they rely on to make a living, would not be factored into their property taxes. The overwhelming majority of land value in the US, and indeed in all countries, is within cities.

Fine, but would farmers even be supportive of this?

This idea of taxing land to make it more attainable to those who genuinely want to get into farming is not a new one. In Denmark, the land tax was championed by farmers more than anyone else. The Land Value Tax in Denmark had been rooted in a movement to free the peasant farming class from the landlords that goes back as far as the 1780s. This movement was wildly successful at putting land in the hands of the farmers who worked it productively. Due to the success of the land tax, and some other policies, “within a few decades a class of independent owners of small farms was created, numbering in the hundred thousands. While the Danish farmers had, until 1788, hardly owned any land, an 1873 census counted 70,959 small farms and 131,162 small plots.”12

In the very early years of the 1900s, this legal tradition came under threat as large landowners came into control of the Danish Liberal Party. Sensing this threat, a group of representatives from about a hundred agricultural cooperatives met in the town of Köge in 1902 and passed a resolution that included the following passage:

“The Smallholders Association does demand…the earliest possible abolition of all duties and taxes which are imposed directly or indirectly on consumer products, as for example food stuffs, clothing, buildings, livestock, tools, machinery, raw materials, and labor-produced earnings, because such taxes place an unfair burden on labor and on the little man. In their place, the Smallholders Association asks that, to cover public expenditures, that value of the land be taxed which is not derived from individual labor, but which is due, rather, to the growth and development of society. This value reaches, especially in the large cities, tremendous proportions and enriches, undeservedly, private speculators, instead of being collected by the State or the community. Such taxes will not inhibit labor, but will make the land cheaper and will enable everyone to establish his own home (Silagi et. al).

Although these farmers were already landowners, and already quite successful farmers, they correctly saw land values as the most appropriate source of tax revenue to be collected. If land values were taxed, the government could still be funded, while agriculture would remain competitive, innovative, efficient, and even cooperative because it made it very difficult for land to be consolidated into the hands of a few bloated operations at the expense of everyone else in the industry. If their other properties were taxed, there would be downward pressure on the farmers, and indeed on all workers and businesses.

This idea was intuitive enough to not just take hold in Denmark, where it was already part of an established tradition, but also in America. In 1886, black farm owners, sharecroppers, and farmhands in Texas formed the Colored Farmers National Alliance and Cooperative Union. Within five years, this organization had spread from Texas to all of the former slave states. While some members of the Colored Farmers Alliance were landowners themselves, most of the good farmland in the south ended up right back in the hands of former slave owners who previously held it. The black farm owners were left with smaller plots of inferior land, and most black farmworkers were landless renters.

Historian Charles Postel writes in The Populist Vision, “The Colored Alliance made no claims based on past servitude, nor did it propose land reform to divide properties of the plantation owners. Rather, Humphrey and the Colored Alliance championed Henry George's taxing system. The San Francisco-born reformer had designed his tax proposal as a means to break the grip of urban real estate moguls and the great western land speculators. The leaders of the Colored Alliance found it equally promising as a means to break the white land monopoly by reducing the tax barrier to property ownership and by compelling large owners to sell off unimproved land. "There are already millions of our people, colored and white, who favor this single tax plan," Humphrey argued, and "its enactment into law would place homes within reach of all the people."13

In that same decade, the Populist Party emerged from a coalition of agrarian radicals and urban laborers concerned about the increasing power of landowners, monopolistic businesses like railroads and telephone companies, and the gold standard, which they believed benefited bankers and industrialists at the expense of workers and farmers. Although not all Populists were Georgists and the party's Omaha Manifesto did not explicitly support land value taxation, many members were influenced by Georgist ideas. The Manifesto included a key excerpt reflecting the spirit of land value taxation: “The land, including all natural resources of wealth, is the heritage of all the people and should not be monopolized for speculative purposes. Alien [absentee] ownership of land should be prohibited. Lands held by railroads and corporations beyond their needs, and lands owned by aliens, should be reclaimed by the government for actual settlers only.”14

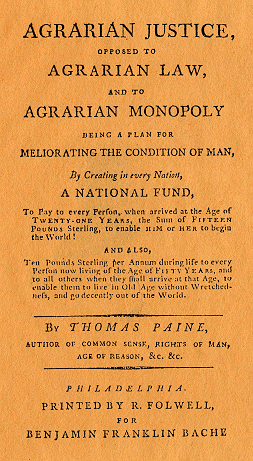

Earlier still, Thomas Paine, the most radical of the American revolutionaries, wrote a short book called Agrarian Justice. In it, he lays the philosophical foundation for later thinkers like Henry George. Paine argues that the entire Earth, in its uncultivated state, is the natural right of every person. He believed that private property is necessary to distinguish between individuals’ labor and that it promotes increased production. At the same time, by allowing people to own land, society has chosen to perpetuate poverty, as free access to land is essential for self-sufficiency. Those without property are always at the mercy of landowners.

Paine contends that while landowners should be allowed to own land, “as it is impossible to separate the improvement made by cultivation from the land itself,” they owe compensation to the public for the privilege of enclosing land that properly belongs to everyone. He continues, “Cultivation is at least one of the greatest natural improvements ever made by human invention. It has given to created earth a tenfold value. But the landed monopoly that began with it has produced the greatest evil. It has dispossessed more than half the inhabitants of every nation of their natural inheritance, without providing for them, an indemnity for their loss, and has thereby created a species of poverty and wretchedness that did not exist before.” He states, “It is not charity but a right, not bounty but justice, that I am pleading for. The present state of civilization is as odious as it is unjust. It is absolutely the opposite of what it should be, and it is necessary that a revolution should be made in it. The contrast of affluence and wretchedness continually meeting and offending the eye is like dead and living bodies chained together.”15

Paine proposes the first version of a social safety net in American history and the earliest form of a universal basic income (UBI). He suggests that an inheritance tax on landowners should fund healthcare and provide a lump sum to every young person starting out in life. Although the math behind his proposal is much more convoluted than the simplicity of the Land Value Tax, the spirit is the same. Criticizing conventional charity, he writes, “It is the practice of what has unjustly obtained the name of civilization (and the practice merits not to be called either charity or policy) to make some provision for persons becoming poor and wretched only at the time they become so. Would it not, even as a matter of economy, be far better to adopt means to prevent their becoming poor? This can best be done by making every person when arriving at the age of twenty-one, an inheritor of something to begin with.”

He believed this would help to break up large estates and provide people with homes and land, stating, “When a young couple begin the world, the difference is exceedingly great whether they start with nothing or with fifteen pounds apiece. With this aid, they could buy a cow and implements to cultivate a few acres of land. Instead of becoming burdens on society, which is always the case when children are produced faster than they can be fed, they would be put in the way of becoming useful and profitable citizens.” Although not a farmer himself, Paine saw that taxing land would allow more people to access it and work it productively, which in his time mostly meant farming.

In summary, yes; Farmers and others who supported farmers in the past have understood the implications and supported the land value tax as well as other measures similar to it. Those farmers who saw themselves not as investors but as workers, as producers, have historically been very supportive of it as a way of protecting the right of people to access the land that they need to make a living.

But The Big Farms Are Subsidized, How Can We Compete?

While it’s true that commodity farmers mostly grow crops within subsidy programs, there are several state and federal programs designed to help small farmers get started and be supported as well, but the amount of money put into these pales in comparison to the total amount of money that goes into government programs that commodity farmers use. We can see this as either a smart policy that encourages domestic food production and ensures cheap consumer goods, or as a waste of public money propping up an uncompetitive industry that should change rather than be paid to continue along its current path. While small farmers should make use of all available tools to help them, there is a subtle way in which taxing land can address this issue as well.

For commodity farmers, if the market value of corn or soy falls below a certain amount, the state will step in to make up the difference with a price floor that they had set earlier. This confidence in the ability to sell these crops at a certain price leads to more land being put into those crops than crops that may be worth more on the open market. Commodity crops are then grown in such quantities that they are not a very profitable venture. However, the real effect of crop subsidies is that they raise land prices, and farmers who own land are beneficiaries of this more so than they are beneficiaries of the value of the crops themselves.

The primary benefit of land value growth as a passive profit strategy is that those gains grow untaxed and allow for farmers to draw equity from the land if they so choose, similar to how the megarich draw loans against the value of stock, and as long as their draw is less than the gained growth of their property, they can draw from this value on an infinite timeline without having to pay tax on those gains. Further there are tax strategies such as 1031 exchanges, which allow for similar sale and purchase of property, which can defer tax on the sale of property. More recently, other tools such as Delaware Statutory Trusts, Opportunity Zone Funds, and 721 exchanges which have allowed land-owners to diversify and stretch what exactly constitutes the “like-kind exchange” premise which underlies this practice.

If a farmer knows that he or she can make a certain amount of corn, regardless of what the actual market value is, they will be more inclined to pay higher prices to access more land to put into those crops, which means landowners are the ones actually benefiting from these policies. Demand for their farmland increases, and they either rent to a farmer for the higher price, or pocket that gain as imputed rent.

Land Value Taxation has a side benefit here that renders small farmers much more competitive against subsidized farms than under the current system. Because the tax is relative to the assessed value of the land, and farmland is made more valuable when subsidies can be applied to the crops farmed on it, the tax becomes higher the more subsidies flow into the price of land, at least partially negating the effect of subsidies (depending on the rate at which the tax is applied in the particular locality). If one cannot profit off land as an investment, the benefits of subsidies are greatly reduced compared to simply growing crops that are worth more.

Dr. Pickard says this;

The removal of grants and subsidies need not to have a negative impact on the profitability of farming. Without the burden of existing taxes, farmers would be able to return to farming and concentrate on producing the goods that consumers want. Those who are convinced that unsubsidized farming can never be profitable can take comfort from the fact that if farmers are unable to generate profit (which means the land they occupy would not attract rental charges), there would be no payment to the exchequer. But when fixed costs have been reduced, there is little doubt that a taxable surplus will be produced…Instead of farming to maximize subsidy income we would pay more attention to the demands of the market. When incentives to maximize the amount of land owned is replaced by the incentive to maximize profits through the ability to keep what we earn, the vitality of rural communities will return.16

Putting It All Together

It is my hope in writing this to show that there is a viable path forward for those who believe our farming system could use a change. It is not my intention to contradict arguments by those who have written about their preferred methods to get around or work within the behemoth that is our current agricultural system, but rather to compliment it. I applaud those farmers who have been clever and hardworking enough to figure out how to make a living farming, or even just lucky enough to be given an opportunity and not take it for granted. But there is a tendency within all movements to overapply one prescription to all situations and believe that it can fix everything.

At the risk of doing the same thing myself, I would like to offer this: that land value tax is not a silver bullet, but a starting point. It will not fix anything by itself. But without it, we are all swimming against a current that is baked into our economy, and only a small handful of people will be able to make any progress. These few often become blind to why the rest struggle, and though it is not their fault, their success perpetuates land access issues. Those inspired by their success who wish to try their hand at farming face even fiercer competition. The state can pass any number of arbitrary laws limiting land ownership to certain amounts, barring certain individuals or companies from owning land, or trying to subsidize the activities it wants to see more of, but none of these are complete solutions because they fail to address the root of the problem. At best they temporarily provide relief, and sometimes they make the problems much worse.

The current "small farm" movement is driven by a desire for a more sustainable and community-oriented approach to agriculture. While I am sympathetic to these goals, focusing solely on farm size is somewhat arbitrary and misses the broader issue. The real challenge lies in the commodification of land. Whether a farm is large or small, what truly matters is how the land is used and who benefits from its productivity.

The commodification of land turns it into a speculative asset rather than a productive resource. This leads to the land being concentrated in the hands of a few, driving up prices and making it inaccessible to many aspiring farmers. Since the use of the land offers less of a reward than the ownership of the land, there is no way of internalizing the cost of long-term environmental damage or the cost of social damage that comes from land being inaccessible to people.

Instead of idealizing certain-sized farms, we should aim to create a system where land is utilized efficiently and responsibly, regardless of farm size. Placing the tax burden more fully on land values ensures that land remains accessible to those who wish to farm it and supports diverse agricultural methods, fostering a robust and varied food system.

Urban planners have a term, “the missing middle”, to describe medium-density housing that used to be commonplace. It refers to structures that fall within a fairly wide range of sizes that reduce urban sprawl and maintain enough housing to meet demand, like duplexes, quads, or townhouses. LVT is touted as a solution to bring back the missing middle in urban and semi-urban spaces. I think it could bring back a missing middle to agriculture as well by creating the conditions for farms to thrive between the extremes of tiny market gardens and the massive commodity farms that have become normal today. We can maintain the benefits of mechanization and efficiencies of scale, but without scaling so large that additional land represents diminishing returns. Likewise, it can raise demand for labor and encourage better wages in agriculture without idealizing tedious and often physically harmful work that comes from not having appropriate technology to assist in labor. Within this range, a vast number of things are possible.

Though the idea of taxing land is economically sound, on a practical level it may be worth considering a gradual transition, using split rate taxes (meaning that rather than simply placing all the tax burden on land and none on improvements, land is simply taxed at a higher mill rate than improvements, creating a sort of halfway version of LVT), or giving tax credits to current landowners during a transitional period so the idea is more palatable. That is something best left to each town or county. My intention is simply to plant the seed of the idea in the minds of farmers and activists so that they can consider it.

For those skeptical of changing local policy, establishing Community Land Trusts (CLTs) is a co-operative way to achieve similar goals. CLTs are nonprofits that acquire land through purchase or donation (and our piece on scythes with the folks at Fox Holler Almanac highlights this model to an extent). The trust retains ownership of the land and leases parcels to members, who own the buildings and improvements but not the land itself. Members can use the land according to their own and the trust's goals, such as conservation, farming, or providing affordable housing. They can sell their buildings and improvements and are free to make whatever money they can while conducting business, but the equity in the land is either collected as rent or capped at a certain percentage. Trusts can then use this money to invest in infrastructure that benefits community members or acquire new land, ensuring future access to affordable land within the trust.

There are already land trusts focused on preserving farmland and wildlands all over the country, as well as those that specifically lease land to beginning farmers. These are called “incubator farms”. The prospective farmer rents land from the trust for a handful of years, allowing the farmer to develop their skills and build a customer base while avoiding the upfront cost of acquiring land, in hopes that they will be able to buy land later and continue building their business. There is no reason that more of these could not exist, ensuring long-term affordable land access to not just beginning farmers, but even well-established farmers who would sign multi-decade long leases. These models hold immense potential to be studied, replicated, or modified, without having to wait on slow political change, though of course their utility is limited to within the land owned by the trust.

Our farming population and rural communities are shrinking, but taxing land values is a straightforward solution to boost labor demand, revitalize rural areas, and enhance food production while promoting the efficient use of our most precious resources - land, air, and water. This can be achieved through a simple adjustment in property tax collection, which will encourage efficiency without imposing additional requirements or heavy-handed state intervention. Historical precedents show this policy's success in both rural and urban settings.

Land value taxation benefits all farmers who utilize resources effectively. For example, farmers like Hannes Botha from South Africa, who switched to a new grazing philosophy and reported in a webinar, “I was able to double my farm’s carrying capacity in a single season; it was like buying a second farm,” are prime examples of those who would benefit most from this system.17

Jim Gerrish, a grazier and author, similarly describes what he calls a “head slap moment” when he realized that the way to maximize his farm’s forage and reduce his winter feeding costs was to “stock the farm to its winter grazing capacity and then consume the spring forage peak with additional animals”.18 Grazing with variable stocking densities is a more complex system than traditional grazing, but it allowed Gerrish to greatly reduce the single largest expense in his operation; winter hay feeding. Farmers like these who innovate to maximize their land’s potential to produce will benefit immensely from shifting the tax burden on to land.

And it is important to point out again, that our current system of taxation creates the situation we are in by placing so much reward in owning land, and so little reward in growing food (oftentimes actually paying farmers not to grow food!).19 Conventional farmers are not malicious or stubborn. Adopting new practices is highly risky, when the reward is fairly low to begin with, especially when your assets are appreciating in the background anyway. These farmers are acting intelligently given the conditions they are in. That is why our work must first be to change the conditions, rather than wasting energy trying to force new ideas into a context where they are not economically viable.

A change in perspective is needed. Instead of taxing people on products of their labor, we should be collecting taxes based on what is removed from our common stock of shared resources. We should pay for what we take, not what we make. Under this framework, the size of a farm or any other business is not important as a matter of justice or morality, because growth can not come at the expense of others, and society is fairly compensated for its loss regardless. So, instead of framing the debate as “big ag versus small farms,” we should view it as a much older conflict that is simply unresolved to this day: Productive working people versus the landed gentry.

Let the Land Tax separate the wheat from the chaff once and for all, and may the landlords finally leave the land to those who work.

And so with the farmer. I speak not now of the farmers who never touch the handles of a plow, who cultivate thousands of acres and enjoy incomes like those of the rich Southern planters before the war; but of the working farmers who constitute such a large class in the United States—men who own small farms, which they cultivate with the aid of their boys, and perhaps some hired help, and who in Europe would be called peasant proprietors. Paradoxical as it may appear to these men until they understand the full bearings of the proposition, of all classes above that of the mere laborer they have most to gain by placing all taxes upon the value of land.20

-Henry George, from Progress and Poverty

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 41-page chapter, of (so far) a 1308-page book with 939 sources, you can support our work in several ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

MSN. (n.d.). https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/agriculture-secretary-raises-alarms-over-protecting-small-and-midsize-farms/ar-AA1gWOL2

Pickard, D. (2004). Co-Operation and Competition. In Lie Of The Land (pp. 36–36). essay, Land Research Trust.

Garland, H. (1891). Under the Lion’s Paw. In Main-Travelled Roads (p. 135). essay, Harper & Bros.

Winters-Michaud, C., & Callahan, S. (2022). Farmland Ownership and tenure. USDA ERS - Farmland Ownership and Tenure. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/land-use-land-value-tenure/farmland-ownership-and-tenure/#:~:text=A%20majority%20of%20U.S.%20land,the%202017%20Census%20of%20Agriculture

Gaffney, M. (2007, May). George In The 21st Century, Part 2. Mason Gaffney / George in the 21st century, part 2 -- 2007. https://cooperative-individualism.org/gaffney-mason_george-in-the-21st-century-part-2-2007.htm

Pickard, D. (2004b). Exodus & The Price of Land. In Lie Of The Land (p. 19). essay, Land Research Trust.

Cleveland, P., & Sources: (2014, February). Sustainability Squared. Sustainability Squared | Dollars & Sense. https://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2014/0114cleveland.html

Hoskins, S. (2022, February 28). Who made the land value?. Who Made the Land Value? - by Stephen Hoskins. https://progressandpoverty.substack.com/p/who-made-the-land-value?s=r

Agricultural Land (% of land area) - united states. World Bank Open Data. (n.d.). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.ZS?locations=US

Florida, R. (2017, November 2). America’s urban land is worth a staggering amount. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-02/america-s-urban-land-is-worth-a-staggering-amount

Wunderlich, G., & Blackledge, J. (1994, January 1). Taxing farmland in the United States. AgEcon Search. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/308282?v=pdf

Silagi, M., & Faulkner, S. N. (1994). Henry George and Europe: In Denmark the Big Landowners Scuttled the Age-Old Land Tax but the Smallholders, Moved by George, Restored It. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 53(4), 491–501. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3487193

Postel, C. (1970, January 1). The Populist Vision : Postel, charles : Free download, borrow, and streaming. Internet Archive.

Populist Party platform of 1892. Populist Party Platform of 1892 | The American Presidency Project. (1892, July 4). https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/populist-party-platform-1892

Paine, T. (n.d.). In Agrarian Justice (pp. 25–33). essay, Social Security Works Education Fund.

Pickard, D. (2004a). Bright Potential And Gloomy Prospect. In Lie Of The Land (p. 48). essay, Land Research Trust.

Weekly, F. (2021, October 21). Regenerative grazing management. Magzter. https://www.magzter.com/stories/Business/Farmers-Weekly/Regenerative-grazing-management

Gerrish, J. (2010). Acheiving A Variable Stocking Rate. In Kick the Hay Habit (p. 55). essay, Green Park Press.

Brown, H. C. (2021b, April 29). The Biden Administration will pay farmers more money not to farm. The Counter. https://thecounter.org/biden-administration-farmers-conservation-reserve-crp-usda-vilsack/

George, H. (n.d.). Of The Effect Upon Individuals and Classes. In Progress And Poverty (p. 202). essay.