Scott Nearing is another name that likely hasn’t reached most folks’ ears who may be searching for leaders in the agriculture-socialist-homesteader space, but Scott’s career spanned a wide and varied path from academics to activism to homesteading. His life was as diverse as it was long, and much of what we know from the counterculture movement of the 70s that centered on self-sufficiency stemmed from his specific brand. Born August 6th, 1883 in the steep hills of Morris Run, Pennsylvania, Scott grew up along the edges of what little remained of the original forests that had once been commonplace across the region. The town of Morris Run was functionally run by his grandfather, as it was a company town and Scott was given all of the privileges that came with it. The first of six, he was largely homeschooled by his mother, as the small mining town’s educational system was a one-room schoolhouse, and upon becoming a teenager, his mother rented a home in Philadelphia to put all of the children through a proper public school education.

While in high school, Scott was no longer hidden in a world that bowed to the surname Nearing— he studied and became intimate with the manipulation that drove local politics and the role the church had in the process, all of which turned him vehemently against both the church and public office. He learned about how his classmates lived and found it a jarring and stark contrast to the standards of living he had been used to.

He went on to graduate from Central Manual Training High School in 1901 and enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School on scholarship, where J. Russell Smith was also finishing up his Masters degree at the time, and who would later be a close friend.

While Scott found Wharton particularly boring, he was inspired by one professor, Dr. Simon Nelson Patten, who exposed him to both Socratic-style classrooms but also economics based in abundance— that the world had enough and it was simply a social issue to make sure everyone received what they needed. This inspired Scott to use his education in Business Administration as a teacher, and he spent his free time working with the Pennsylvania Child Labor Committee to end the use of child labor in mines, something the conservative legislature of the time would never let pass. While still connected to the academic world, he was exposed to the single-tax town of Arden, Delaware, where he would become intimate with the Georgian tax system and the overlaps between these small government advocates and the swelling popularity of other socialist positions.

Early on, it became evident how different his life would be living independently on a teacher’s salary. He made it a firm decision to plan on retiring at 40 and to live as simply as possible to do so— much to the chagrin of his family. Scott began his teaching career at Temple School of Theology and taught elementary economics courses at the Wharton School. From 1911 to 1916, Nearing, J.R. Smith, Rexford Tugwell, and a few others who were part of the teaching staff would meet to discuss issues of shared concern— primarily issues around wage labor and capital. While Smith was concerned primarily with conservation, Nearing narrowed in on child labor laws— or the lack thereof.

What’s critical to understand is that the Wharton School, much like the small town of Morris Run, where Nearing had grown up, was fundamentally supported by the company coal town model. The Wharton family made their money from coal mines, the communities around the school were built on coal mines and company towns, and coal mines and company towns were built on child labor. More than once, Nearing was reminded of this fact and was frequently told by other academics to back off his vocal criticism of child labor.

Nearing was constantly reminded that his job was at risk— his part-time teaching gig at Swarthmore College ended early, despite his success with the students, because of a supposed “lack of funding”. Fortunately, he took every free opportunity to speak publicly, bringing in speaking fees which later turned into writing gigs on economics and politics. Shortly, writing was his primary source of income, even though teaching made up the bulk of his time.

“In regular business practices, these items [labor, materials, overhead costs], subtracted from gross income, give net income. When these usual business deductions are applied to the financing of a moderate-sized wage-earners family, they show not a net income but a net loss or deficit. The worker is taxed on his gross income, his total wage or salary, while the businessman is taxed on his net income. As long as big business controls public life in the U.S.A. this scandalous discrimination will continue.”1

As tensions rose on the eve of World War One, the hunt for “subversives” grew and worked its way into universities. As Nearing finished his ninth school year with Wharton, he left his desk to spend the summer in Arden, as he had for the past decade. Upon arriving, a letter awaited him announcing that his contract would not be renewed and he was effectively released of any and all duties with the university on June 16th, 1915.

His removal was legal, but not standard procedure— typically staff were told in April so they would be able to find another position for the following fall. Nearing, Smith, Tugwell and others organized a mass newspaper blitz to announce his wrongful firing.2 Nation-wide dialogue erupted around the concept of free speech and the rights of individuals to speak as they wish outside of the workplace.

Beyond this, Dr. Witmer, from Wharton’s Department of Psychology, was so enraged about the incident he spent the entire summer writing a book entitled The Nearing Case: The Limitation of Academic Freedom at the University of Pennsylvania by Act of the Board of Trustees. While this would be expected possibly from a close friend of Nearings, he and Witmer saw eye to eye on nothing and didn’t much care for one another. Witmer did, however, understand that the question of academic freedom was much larger than his dislike and disagreements with Nearing. He even publicly stated that:

“The first step toward the deterioration and integration of the institution of which they are legally the administrators in trust for the entire community... I hold no brief for Professor Nearing. I respect his honesty, his courage and his social sympathies, but I do not agree with all of his economic views, nor do I approve some of the methods which he employs in placing his views before the public. Nevertheless as a member of the faculty I would consider differences in opinion and method as immaterial, and if called upon I should recommend the appointment of men with whom I disagreed even more than with Professor Nearing.”

Nearing was not reinstated but found a new home at the University of Toledo, Ohio. He quickly connected with the radicals in the region and was active in the community, only to be forced to resign after one year. He recalled the repeated mantra by those who voted for his dismissal that it wasn’t personal, that they liked him and appreciated his work, but the pressures of wartime nationalism demanded that there was no room for voices like his in academia. This would be his last teaching position.

That summer, he once again headed back to Arden, where he was living as World War One broke out. During this time, Federal authorities took out a search warrant for his office at the University of Toledo, scouring through his files and documenting what they could. Scott worked closely with the anti-war movement as many peace organizations began to coalesce to send one clear message to the United States government— no more war. In New York City, organizers purchased a building at 7 East 15th Street they called The People’s House of the Rand School of Social Science, which would be a central location for education, lectures, and books. Nearing was quickly hired to its teaching staff that fall in 1917.

While at the Rand School, Scott also wrote radical pamphlets, despite the risks associated with being anti-war as World War One raged on. Radicals were being arrested for opposing the war, for inciting youth to refuse service, and more. Presidential candidate Eugene Debs was incarcerated at this time, and Nearing wrote a pamphlet entitled The Great Madness, outlining how global capital demands warfare for a number of reasons, at the cost of the working class. Nearing was indicted by a Federal Grand Jury in 1918. Instead of attempting to thwart any responsibility for writing the piece, he instead chose to use the witness stand as a pulpit, having his lawyer request he explain all parts of the pamphlet itself, and in many ways made a mockery of the process.

The courthouse was filled with both national and international reporters, due to Nearing’s stature. In Nearing’s own words, the advertising the pro-peace and socialist movement got from the news outlets was worth millions.3 After 30 hours of deliberation, he was found not guilty and the Rand School was charged with printing the material, which came with a $3,000 fine. You can read in far more detail about his exquisite management of the courtroom in The Trial of Scott Nearing and the American Socialist Society, if you can find a copy.

While the case was won, what little freedom he had for his work was lost. He was contacted by MacMillan Publishing, which had released six of his books. They would no longer publish them. He had lost his teaching, his speaking opportunities, and his publishing.

After the war, Nearing found himself rudderless and decided his best path was to follow his passions. This led him to the Soviet Union in 1925 to study their educational system (which can be read about in Education in Soviet Russia) and to China in 1927, only ten years after Liberty Hyde Bailey had returned, but now in the throes of internal struggle. While in China, as socialists were slaughtered for speaking against the Republic and Chaing Kai-shek, Nearing was invited to attend the Friends of the Soviet Union Conference in Moscow, where he shared the room with Stalin and others.

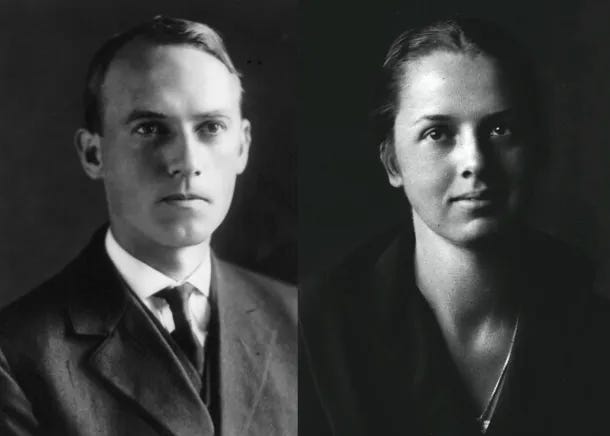

Nearing joined the Communist Party and worked to write and speak on their behalf at events. Meanwhile, he continued to research, and when his research on the origins of imperialism wasn’t in alignment with Lenin’s analysis, he had the choice of not publishing or expulsion. When he was expelled, once again, he was told it wasn’t personal— a recurring theme. From this point forward, Nearing refused to formally associate with any party, although his politics remained on the side of the working class. It was during this time he would meet his future wife, Helen Knothe.

Unable to publish and with an increasing crackdown on public speech for anti-capitalists, Nearing found himself speaking largely in Canada, and in the meantime developed the Federated Press, alongside other writers, to have an outlet for his writing and the work of others. As the build-up to World War Two increased, he was pushed out of his own press for his anti-war position in 1943.

Before, however, he published his six-part series from his travels in the Soviet Union & China, which he had printed by a doctor-turned-printer Bob Leslie. He traveled the country by rail with a friend Sam Krieger to distribute them, and then-unknown Ruth Stout operated as a voluntary secretary for the enterprise which ultimately spread several hundred thousand pamphlets across Canada and the United States between 1927 & 1929 under the name Social Science Press. Between 1917 and 1937 Nearing published nearly thirty books, largely independently.

The Nearing Homestead

During the Great Depression, Nearing wrestled with what his place was within the world in which he was blacklisted, his solution was to disconnect from the system that fed the war machine— and for him, this meant homesteading. In 1932, he moved from New York City to the Green Mountains of Vermont.

Soon after arriving, they purchased land next to their farm for timber production. They never got around to clearing the timber, and deeded the land to the town of Winhall in 1951 to be protected and used by the commons as it is today. Part of the reason why the Nearings never cleared the land was because, in 1934, the farm next door sold off their sugar bush to them, with all of the necessary equipment. After the first season, it became clear to the Nearings that a season of sugaring could pay all of their bills and allow them to live what they called the Good Life.

Part of Scott’s goal was to find ways to integrate— to immerse himself— into the local landscape. To him, this didn’t just mean food that was grown locally, but construction that reflected the landscape— which to him meant the vast amounts of stone that frustrated farmers since the arrival of colonists. Throughout his time in Vermont, he and Helen built over a dozen stone buildings using the Flagg system, a largely DIY-designed stone building method advocated by Ernest Flagg, also known as slipform stone masonry.

For eleven years, Scott and Helen would spend most of their year building these stone buildings for various uses— sugar houses, guest houses, garages, storage buildings, wood sheds, and more.4

While the Nearings could be described as poor, their only real need for cash was for property taxes— they had no electricity, no refrigerator, and very few expenses. Helen would say “we were poor in the country, but it was better than being poor in the city… Instead of eating out of garbage cans, we ate out of our own garden.”5 It was here they would write their first book on maple sugaring and Scott would continue to write as he could to earn a small income.

However, as they had settled into their Vermont home, a recent purchase and development of a nearby ski resort led to the Green Mountain Valley tourist trap we know today. Between this influx of newcomers and their frustrations with developing a meaningful sense of collective labor and mutual aid, the two decided to pick up once again and headed to Maine. At this time they felt it was worth writing down their lessons learned. Starting over and already 72 years old, Scott and Helen wrote “Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World”, which was quietly published in 1954.6 The publisher who had released their other recent book on maple sugaring had implied that he was interested in publishing it. However, a stroke made that no longer possible, and the Nearings chose to self-publish the book, under the publishing house the Social Science Institute.

While we don’t have firm information, it’s suspected that no more than 3,000 copies of the book were distributed in the first printing. Only a few decades later, under the weight of the hippie movement, it was republished in the 1970s and quickly sold out over 50,000 copies. The back-to-the-land movement had been just born and the Nearings guide would be their bible.

While the book provides meaningful explanations on how to live “sustainability”, a particular draw from the book is that they proclaimed they only work as hard as they have two, which often meant working only part of the year, largely because of the profitability of the maple sugaring season. Their days were described to be broken into three 4-hour chunks— one for work, one for civic duty (value for their community), and one for personal interests. Understandably, this was attractive to many readers trapped in or staring down the barrel of a lifetime of a 9-5.7

The Nearings highlighted that individuals could, in theory, live by their own labor, almost entirely outside of the capitalist system, or that was their vision. Of course, it was more complicated than that. Their ability to survive was dependent on machinery that would only exist affordably because of mass production and the horrid conditions that made much of suburban and rural luxuries possible (from the dynamite used to break stone to the trucks he borrowed to haul it). Ultimately, this isn’t an all-or-nothing approach, but rather an attempt to position their vision and problem-solving within real-world parameters.

Their new home on Penobscot Bay in Maine, lovingly called “Forest Farm” was something of a Mecca visited by hundreds of back-to-the-land pilgrims by the 1970s. After two decades of farming the new homestead, it became too much management for the Nearings, and sections were sold off, piece by piece. As Scott grew weaker, it was only when he could no longer carry firewood at the age of 100 that he decided it was time to go. According to Helen, he simply stopped eating and starved himself to death, at home, while Helen cared for him.8 It would take another decade for Helen to pass in an auto accident.

Their names have remained an inspiration to many, and their farm has been turned into the Good Life Center, where visitors can see the homestead as it was, with an original copy of The Good Life proudly on display.

Another issue has sprung up in more recent years. In 2003, a book by author Jean Hay Bright uncovered evidence that the Nearings’ survival was a bit more complex than previously suggested. Now, Hay Bright herself knew the Nearings quite closely— they had followed the Nearings to Maine and purchased 30 acres of land from the Nearings personally. Hay Bright also was once one of the stewards of the Good Life Center, in fact. All that said, through her research, she was able to find that one of the key components of their financial survival was not on making a living on ‘four hours a day’ as Scott promoted, but rather “Banks, stocks, annuities, monetary gifts, inheritances and unearned income from other people’s labor that kept Scott and Helen going… as far back as the early sugaring days in Vermont.”9

She also levels other criticisms at the Nearings, many of which I don’t find particularly useful in assessing what the Nearings succeeded in doing (they were vegan but sometimes ate ice cream!), but I do believe it’s incredibly important to highlight how financial resources allow us to experiment and fail in ways we cannot otherwise, and I believe this was the case with the Nearings. In their attempts to live outside the system, they were willing to bend the rules likely with the belief that if more people followed them, they could build the mutual aid community that would help them fully unplug from their trust funds. Of course, this was never realized.

The Nearings were by no means perfect— they believed carbonated foods were bad for you, that pickled foods were dangerous to your health, and that raw foods were the ideal food for consumption. They were flawed people. Yet, they still provided hope for millions and were a chief precursor in the development of the back-to-the-land movement, while doing the most human thing of all— attempting to live fully, even if that meant imperfectly.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 15-page chapter, of (so far) a 1050-page book with 699 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #209, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Nearing, S. (2000). The making of a radical: A political autobiography. Chelsea Green Pub. Co.

Square Deal, Volume 1, Number 7, 26 June 1915.

https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TSD19150626&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN--------

NEARING, S. (2018). Trial of Scott Nearing and the American Socialist Society. FORGOTTEN BOOKS.

Nearing, H., Nearing, S., & Nearing, H. (1989). The good life: Helen and Scott Nearing’s sixty years of self-sufficient living. Schocken Books.

https://vtdigger.org/2019/09/29/then-again-early-back-to-the-landers-inspired-a-generation-first-in-vermont-then-in-maine/

https://downeast.com/history/living-the-good-life/

https://vtdigger.org/2019/09/29/then-again-early-back-to-the-landers-inspired-a-generation-first-in-vermont-then-in-maine/

Nearing, H. (1995). Loving and leaving the good life. Chelsea Green Pub. Co.

Bright, H. J. (2013). Meanwhile next door to the good life: Homesteading in the 1970s in The shadows of helen and Scott Nearing, and how it all - and they - ended up. BrightBerry Press.