The Back to the Land Movement

The First post-World War 2 movement to Reconnect with the Land, and Where it Went Wrong

The counterculture movement of the 1960s and 70s is well-known, and its trappings of communes that were woefully prepared for the work required to survive has been made fodder for more than one trope from this era. We’ll explore this well-worn narrative, but to do so, we need to frame up where the Back-to-the-Land movement originated to understand how it became what is so well known.

While we didn’t cover it in-depth, it should be unsurprising that there was a large homesteading movement during the New Deal era, and this is where much of the 1970s Back-to-the-Land movement found its roots. After all, when there are no jobs, there’s always one way to get food— to grow it. To this point, we’ve largely ignored the homesteader movement and focused on its critics and the leaders of collective movements for coalescing sustainable food systems. That said, the Back to the Land efforts of the 70s found their beginnings in the 20s and 30s.

We had spoken during the New Deal era about Rexford Tugwell’s push for homesteader communities— what was interesting during his work advocating for these communities is that many who painted him as a communist hell-bent on destroying America also supported his vision of decentralizing food and community— such as many of the Southern Agrarians, whose biggest contribution to agrarianism was to somehow make racism worse, implying that the enslaved ruined the relationship of white men with the land.1 Ralph Bordosi, something of an anti-capitalist free marketer, founded the magazine Free America, which, despite its hatred of government and corporations, found itself asking for Tugwell to spend more money on these settlement projects, and for more similar projects such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, which returned power to rural communities from urban centers.2 Coincidentally, one of Free America’s first advertisements was for maple syrup from Helen & Scott Nearing’s first farm.

Part of this decentering of power that Bordosi envisioned focused on the revival of regional identity through cultures and religions, which had been lost under the wheels of national corporations (a sentiment shared by the Southern Agrarians for much worse reasons). This vision was reinforced by poetic novels about rural farmhouses hued in a culture that was often dead or dying.3 These books became so common they were called “I-bought-a-barn” books, and fed into a narrative of self-sufficiency that was unmatched by reality, a trait shared with many of the homesteader movements throughout post-industrialisation.

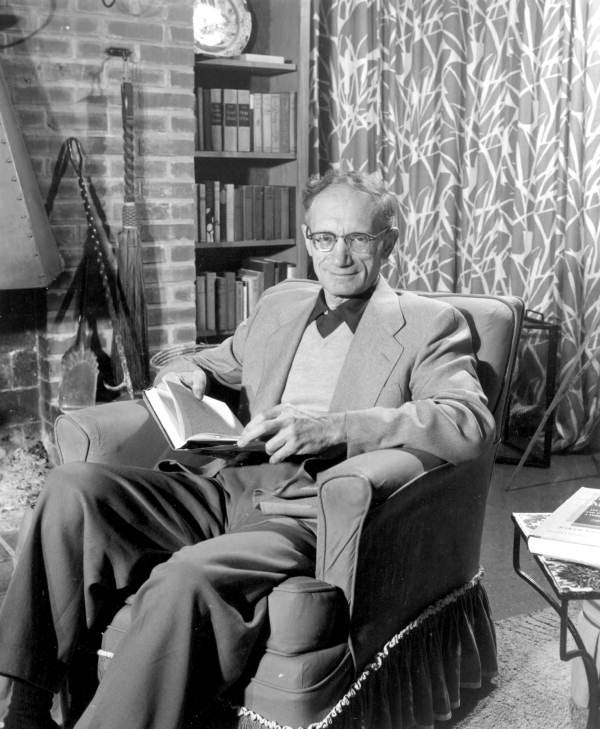

The Back to the Land movement was one of many, as we’ve discussed— from the early days of Liberty Hyde Bailey pointing out the general misunderstanding of agriculture by well-meaning urbanites to the Malthusians of the early 20th century and the Jeffersonian nostalgia that drove the post-dust bowl return to rural communities. As World War 2 rolled in, the government committed itself to the war efforts and pulled out of most of the homesteader communities envisioned by Tugwell. In 1943, the influential Have-More Plan was published by Ed & Carolyn Robinson— a how-to for homesteaders that was written in basic language, that would be the last breath of the Back-to-the-Land movement for a number of decades.

The post-World War 2 Back-to-the-Land movement was unique for several reasons, and we can still trace how it influences homesteading and how homesteading relates to white supremacy, ethnonationalism, and so much more today. Popularity swelled again for homesteading content, driven by an abrupt, temporary reversal of farm-to-city migration, as soldiers and industrial workers returned to rural communities, something we’ll see again after the Korean War, with much more complex implications.4 Despite the initial return of the homesteader movement, by 1954, when the Nearings’ The Good Life was published, interest had already begun to wane significantly, and those who did return to rural life were more often more aligned with contemporary libertarianism who envisioned society as Ralph Bordosi did than over the communal visions that would follow decades later.5

In 1947, Bordosi began his calls that the sky was falling, and that people returned to the land before “Inflation and the loss of their savings, the collapse of the post-war boom, followed by unemployment, or World War III with atomic bombing, makes it too late for them to do so”.6 Of course, this never materialized, and as the post-war boom seemed to be endless, the fears of scarcity stayed at bay until the 1970s.

Many define the Back to the Land movement starting in the fall of 1967, 13 years after Scott & Helen Nearing’s book “The Good Life” was published. The Summer of Love highlighted the tension of increasing urbanization and homogenization under accelerating industrialization and the feeling of a kettle whistling with no one in the house. In 1967, only a dozen or so rural communes existed— within a few years that number had skyrocketed to the thousands. At Woodstock in August of 1969, Joni Mitchell sang “got to get back to the land, and set my soul free”. What happened in those 3 years?

In 1967, the famed Summer of Love was born as various facets of experimental cultures bled into one movement in San Francisco. There was endless hope for a future that was ethically aligned with peace— while at the risk of oversimplifying, it was born out of a generation that had never wanted, with access to new and exciting drugs, limitless opportunity, and a general disgust of war after seeing what it had done to their parents. The movement believed in radical peace and mutual aid, whether it was through the Diggers and free stores or free medical services offered by Haight Ashbury free clinics, it was clear the future envisioned would be voluntary, and it was inevitable.

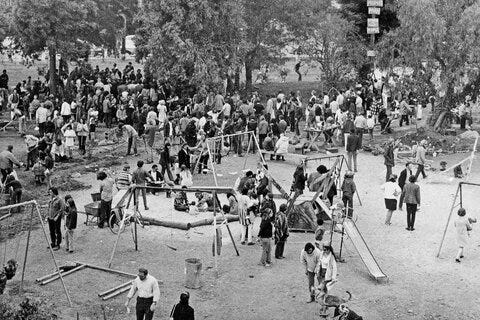

While this has been often identified as the moment of rebirth for the Back-to-the-Land movement, its refocus from changing society from the inside to changing society from the fringes becomes clear over the following years, and I would argue the movement was born in 1969 when the hard fist of state power violently moved the hippie youth out from the cities and into the country. Specifically, May, 1969.

In May 1969, at People’s Park, in California, then-Governor Ronald Reagan gave police full discretionary power to stomp out a peaceful use of an abandoned parking lot that was repurposed into a green space. One hundred twenty-eight people were hurt and one was killed.7 Only a year later would the famed 1970 massacre take place at Kent State. Political assassinations were too common, cities were on fire under protests and counter protests in response to civil rights protests, and the feeling of endless war was overwhelming for a generation that had spent their entire lives living in the boom of the post-war era.

Unlike the movement of the 30s, or the 1890s that had driven the parents of Russell Lord back to the country, this movement was fundamentally different— the hippies chose to move the country not out of necessity or fears of economic catastrophe but out of hatred for the system itself. A contemporary study called Children of Prosperity (1973) argued that, unlike other Back-to-the-Land movements, these homesteaders were “overwhelmingly white, under thirty, and from economically, educationally, and socially privileged families”.8

In 1970, “The Good Life” was republished and immediately sold out 50,000 copies. It was the same year that Mother Earth News was born and became the primary journal for the movement, with nearly a half-million subscribers in a few years. Bordosi’s Flight from the City was reprinted in 1972, and Rodale Press began reprinting major historical homesteading books, such as Samuel Ogden’s This Country Life in 1973. Mother Earth News also reprinted Robinson’s Have-More Plan and even printed excerpts from Bordosi’s magazine Free America. E.F. Schumacher also published Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered in 1973, which gave birth to the concepts of ‘enough-ness” and “appropriate technology”. A vision was sold, and a generation of young adults bought in.

While the narrative of the hippies living on a commune while collecting funds from mom and dad has been a trope long associated with the 60s countercultural movement, many of the elder leaders of the movement found this narrative to be consistent. The Nearings, whose farm became a mecca for many of these followers, wrote that most of the visitors were “raised in comfort if not pampered in luxury… Never before in our lives [had we met so many] unattached, uncommitted, insecure, uncertain human beings [who were] apolitical, impatient of restraints” and little understood the self-sacrifice and discipline that was necessary and had driven many of the earlier back-to-the-landers.9, 10 Of course, it’s worth noting that part of this criticism from the Nearings may be more reflective of their age and having grown up during a period when order, discipline, and self-control were necessary tools of survival.

The concerns of these new Back-to-the-Landers were different from prior generations as well— there was little worry about not having a paycheck, and little discussion was had about planning for old age or illness.11 Of course, this was likely largely due to the young ages of the movement’s followers, as well as the strong social safety nets of the time. While there were fears about the coming collapse of petrochemical agriculture, it didn’t seem to be a primary motivator for many of these adherents. Like the Nearings and prior movements, this new iteration was critical of vulgar consumerism and especially weary of giving up any sense of self-determination, or in the words of Joan Wells, they were driven to “become master of one’s own schedule and reprogram oneself from imposed city routines.”12 In both our organics and biodynamics pieces, we described how these movements, despite becoming more progressive socially, had concurrently become self-serving and aligned with hyperindividualist values, and this is a major point of that cohesion.

While attacking consumer culture with greater conviction than other back-to-the-landers, their choice to be on the land was both about personal independence and financial isolationism. For many, saving the world had meant saving yourself first. By doing their part— they began to engage with the “green politics” of environmentalism. John Shuttleworth, the founder, editor, and publisher of Mother Earth News, explained how this individualist approach to solving global issues was understood in 1975, stating that “show [a man] how to quit the corporate job he hates… You’ve given that guy’s life back to him, and second, you’ve lessened the impact on the planet as much as if you had cut the population of India by 50.”13

It wasn't just Shuttleworth who paired individuality with revolutionary zeal— we discussed how JI Rodale had done the same with the organic movement, and authors John & Sally Seymour, whose standout Farming for Self-Sufficiency, also makes the case that environmentalism could not happen without self-sufficiency. Without self-sufficiency, the system would crumble and all would fall, setting in place an apocalyptic tone of the future.

These narratives also overlap with contemporary and historical pairings of autonomy with masculinity. The hyper-masculinization of men in particular in the movement earned Mother Earth News the acronym MEN by contemporary feminists, “with its ploughboy interviews and emphasis on a land movement dominated by men”.14 Womens-only colonies sprang up in response to the power dynamics inherent in many of these communities to provide women’s autonomy and independence from men and patriarchy.

Despite equal-work across gender on many communes, for women, their work was always less equal— while bearing the roles of labor, they also carried the conventional unpaid work of the mundane— laundry, carrying water, and so on.15 However, for many women whose expectations had been to maintain a home for their husband, drudgery on top of the mundane allowed them to feel productive and feign some sense of independence.16

Behind the surface of the movement that advocated free love, collective ownership through communes, and radical positivity were deeper undercurrents of the dynamics of capitalism. Gender issues exploited the language of the movement, while self-serving activities were painted as revolutionary activity. Growing corn was an environmental act because you weren’t buying it from the store. Not paying taxes was a challenge on the Korean War. The language of revolutionary politics was applied to selfish endeavors without changing any of the fundamental power dynamics in the new rural environment.

These dynamics also infused every relationship around the homestead, including the inverse rat race that was born out of attempting to live as disconnected to civilization as possible. Inspired by the Nearings, primarily, it became a challenge to find ways to ensure you were influenced by industrial society as little as possible. While many of these homesteaders had come from families with discretionary income, like the Nearings, if you “happened to have a nest egg [you] were careful to keep it quiet and spend it unobtrusively.”17 Aestethic was more important that practice— ideological & personal consistency were illusive for most, if not all Back-to-the-Landers.

The movement continued to grow into the early 1970s, as evidenced by the continued releases of major books in this space, and in 1972, the energy crisis hit. Energy shortages and inflation took hold, and by 1975, much of the writing about the movement changed and began to address some of the same material issues of the past for the first time, such as the need to find jobs.18

As pressures for the movement to show successes, major figures like Mother Earth News’ John Shuttleworth became both more militant about their radical politics, frustrated by the lack of change, and also more nostalgic for the past, blaming “the unholy trio of modern society— Big Government, Big Business, and Big Labor… [which] trample a free and proud way of life underfoot.” Having aligned as an anarchist most of his life, Shuttleworth found himself pulled to the far right, aligning more with the historical leaders of many of these movements, as we have described.

As the dust settled for these new homesteaders, as trust fund checks stopped arriving and the grim reality of homesteading wore many young adults into realizing white-collar work wasn’t as bad as they once thought, many began moving back to their homes. Unemployment continued to climb, and the pressures on families supporting their children’s interests in commune living became too much. Many twenty-somethings returned home and put their degrees to use while others simply got tired of using outhouses and living in poverty. The Back-to-the-Land movement arrived like a lion and quietly ended a lamb.

We can learn quite a bit about the followers of this movement and how they reflect the modern state of homesteading by analyzing the readership of Mother Earth News. In 1977, at the tail end of the Back-to-the-Land boom, a reader survey showed that the average reader was 32, more than 60% of which were college graduates, and three-quarters were homeowners (and made a median yearly income of $18,000— significantly higher than the national median income).19 This narrative highlights one of the critiques readers had of Russell Lords’ The Land magazine in the 1950s— that the magazine was geared towards primarily hobby farmers and ideals rather than working-class farmers.

By the early 1980s, Countryside Magazine’s subscriptions fell from forty thousand to four thousand.20 Mother Earth News resorted to backyard DIY projects to maintain readership. While conventional homesteading content seemed to dry up, other related subjects continued to draw attention, such as alternative energy, organic food, and herbal medicine. By the end of the 20th century, many of these idealists instead wrote books about being “back from the land”, such as the ones criticizing the Nearings for selling an unrealistic vision. Ultimately, it was the purity politics of the movement, of having to disconnect from all society, that all of the changes society needed must be address in their new vision, while never changing the patriarchal power dynamics which underscored day-to-day living. Its inability to create material change, because of these above reasons, not only drove some socialists to the right, but also empowered much of the far-right, as we’ll see in the following piece.

The 1970s Back-to-the-Land movement has, despite its tumultuous path, left us some good tools— the Land Trust model came from collaboration between Ralph Bordosi and Robert Swann. The echo of the movement into the 80s also provided necessary nuance— that the goal shouldn’t be to cut yourself off from society but rather find ways to find enjoyment from these practices while trying to reduce the power industrial society has on your ability to live the life you want. While the changes in Mother Earth News and Countryside Magazine are pointed to as proof of the fall of this movement, instead I see the movement itself mature and engage with its subject matter more pragmatically.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 14-page chapter, of (so far) a 1115-page book with 754 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #212, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Andrew Nelson Lytle, “The Hind Tit,” in I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 216–17.

Ralph Borsodi, “Decentralization,” Free America, Jan. 1938, 4.

Vrest Orton, “Vermont—for Vermonters,” Driftwind, July 1928

Joseph P. Ferrie, “Internal Migration,” in chapter Ac of Historical Statistics of the United States, Earliest Times to the Present: Millennial Edition, edited by Susan B. Carter, Scott Sigmund Gartner, Michael R. Haines, Alan L. Olmstead, Richard Sutch, and Gavin Wright (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ISBN-9780511132971.Ac.ESS.01.

Greg Joly and Rebecca Lepkoff, Almost Utopia: The Residents and Radicals of Pikes Falls, Vermont, 1950 (Barre: Vermont Historical Society, 2008)

Ralph Borsodi, Flight from the City: An Experiment In Creative Living on the Land, rev. ed. (Suffern, NY: School for Living, 1947), xv.

https://news.ucr.edu/articles/2020/03/11/day-60s-protest-movement-came-ucr

Gardner, H. (1973). The Children of Prosperity.

Helen Nearing and Scott Nearing, Continuing the Good Life (New York: Harper and Row, 1979), 360.

Helen Nearing and Scott Nearing, The Good Life: Helen and Scott Nearing’s Sixty Years of Self-Sufficient Living (New York: Schocken, 1989), 358–59.

Paul Edwards, “Report from Them That’s Doin’,” Mother Earth News, Mar. Apr. 1976, 76.

Joan Wells, Downwind from Nobody (Charlotte, VT: Garden Way Publishing, 1978), 4.

John Shuttleworth, “The Plowboy Interview,” Mother Earth News, Mar./Apr. 1975, 7.

Margaret Cheney, Meanwhile Farm (Millbrae, CA: Les Femmes Publishing, 1975), 177–78.

Joyce Cheney, ed., Lesbian Land (Minneapolis, MN: Word Weavers, 1985). These publishers also brought out Maize: A Lesbian Country Magazine

Jeanne Tetrault and Sherry Thomas, Country Women: A Handbook for the New Farmer (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1976).

Agnew, E. (2005). Back from the land: How young americans went to nature in the 1970s, and why they came back. Ivan R. Dee.

Agnew, E. (2005). Back from the land: How young americans went to nature in the 1970s, and why they came back. Ivan R. Dee.

“News from Mother: Who Reads Mother Anyway?” 24.

Jeffrey Jacob, New Pioneers: The Back to the Land Movement and the Search for a Sustain- able Future (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997)