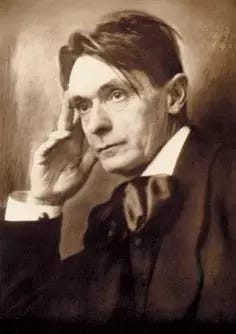

To talk about permanent agriculture and the alternative agriculture movement that fought against monocropping and industrial pesticide and fertilizer use without talking about biodynamics ignores one of the focal components in the development of a huge facet of how these movements came to be today. To try and explain the biodynamic movement without talking about Rudolf Steiner doesn’t fully capture how and why the movement became what it was long after his death. Steiner’s interest spanned from education to agriculture to, in his words, “how to know higher worlds.” His interests explored anthroposophy, or what he considered ‘spiritual science’, something that has continued to occupy a large space in the various ‘natural’ agricultural movements that span the globe today, including at least 6,000 farms today.1 Waldorf schools, inspired by Steiner’s work, number over 2,000 today, and highlight that his writing and speeches struck a common belief that has transcended his place and time in Germany. We’ll explore what these beliefs are and how these positions, by definition of how they can be interpreted, have been coopted by groups across the political spectrum.

The argument can be made that Steiner was a visionary; he adovcated that seeds, when planted, dissolved and the plant itself is created by the forces of “the entire surrounding Universe.” From a literal standpoint, this is obviously wrong, but from a metaphorical position, it highlights what we now understand about the role of microbes, fungi, and bacteria in the germination of seeds into plants. How you choose to assess his writing likely highlights how you are likely to view Steiner’s work as a whole.

From one perspective, he was a visionary theorist wildly ahead of his time, in this way. From another, Steiner was a self-proclaimed clairvoyant and supporter of weird medicine that highlights some interesting strains of what exists in the organic, biodynamic, and generally speaking– anti-scientific wing of the holistic movement. Steiner, for example, believed Mistletoe was a cancer treatment because it was a parasite that killed its host plants. Steiner believed the plant's medical potential was influenced by the position of the sun, moon, and planets and that it therefore was important to harvest the plant at the right time.

So let’s back up and contextualize his work, and how this impacted the development and evolution of the biodynamic movement into what it is today. Within this context, we can fairly analyze his work and understand how it relates to the organic, permaculture, regenerative, agroecological, and homesteader movements that fill the corners of contemporary alternative agriculture today. While we won’t get tied up in some of the complexities of his philosophies, instead we will attempt to speak in broad strokes about his work and the context it was developed. In many ways, speaking as little of Steiner himself best reflects how he expected his practitioners to discuss biodynamics and anthroposophy.

While Steiner is described as a socialist by many of his supporters today and as a quasi-fascist by his opponents, he self-described himself as what he called an “individualist anarchist” who believed that no system would “hold good for all time”, which would likely categorize him as a modern libertarian or anarcho-capitalist today. With the rise of materialist science, Steiner attempted to tie spirituality to contemporary scientific thought, at some points plagiarizing theosophy’s founder, Madame Blavatsky, which is what we will see develop in the New Age movement in the 1970s.2

Part of Steiner’s ability to create a lasting influence stemmed from the organizational structure of the Anthroposophical Society, founded in December of 1912. This organization put his ideas into practice, including the first Waldorf School in Stuttgart— created in 1919 to educate the children of employees at a cigarette factory— as well as The Coming Day, which was a network of cooperative businesses. The fundamental idea behind belonging to the Society involved high levels of commitment, including encouraging members to socialize and transact primarily with one another, which conserves and recycles resources brought into the movement, allowing for the organization to grow.

Steiner philosophy was framed within an esoteric Christology, in which he argues that when Christ died, “the substance of Jesus Christ entered each of us” and that “The Earth is Christ’s Body”.3 While seemingly unrelated, this perspective posits that working with the soil is to connect with Christ, and that the spirituality tied with working with the land and nature was not a pagan practice but rather reinforced Christian values themselves. These cultish aspects continue to exist in modern iterations of the New Age spiritualism which stems from Steiner’s work, as we will see.

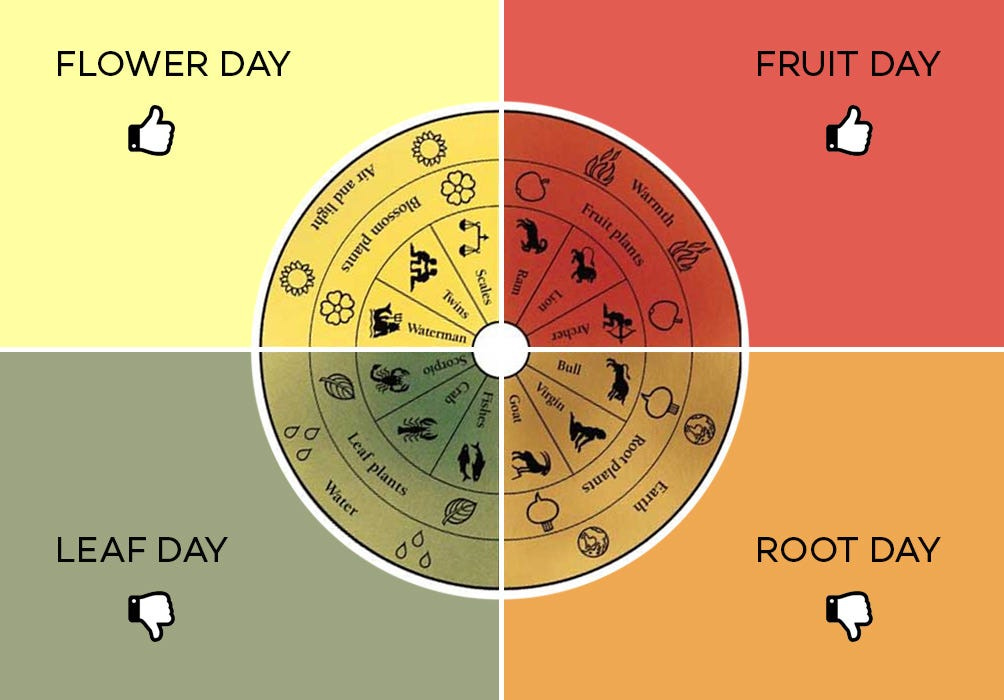

The birth of biodynamics stems from a specific course of lectures by Steiner in 1924. These lectures, only given a year before his death, have little writing and little clarification in later work from Steiner, meaning that much of the application is subjective by adherents and not necessarily ‘codified’ by Steiner himself. In 1927, farmers began to refer to “biological-dynamic agriculture”, which was shortened to “bio-dynamics” in English and later “biodynamics”. The development of his interest in agriculture stemmed from his belief that “nutrition as it is to-day does not supply the strength necessary for manifesting the spirit in physical life”.4 Students of Steiner in the animal sciences had reported increases in animal disease and wanted Steiner to tie these increases to his holistic thinking. It was here where, in 1923, the infamous concept of cow horns filled with manure was born, and he buried these horns in the soil in the fall, only to dig them up in the spring. These would be diluted into a pail of water that was mixed with what he described as an energetic stirring technique, and is known today as “500”.5 The logic behind this was explained that since manure has been inside a living organism, it was filled with astral (nitrogen-carrying) and ethereal (oxygen-carrying) energy, and those would be intensified by placing it within a horn, which would send “the currents inward with more than usual intensity”. The stirring would transfer the energy to the water and establish a “personal relationship to the matter”.

Steiner was also a radical outlier in addressing soil health, that solutions were not atomized changes like machinery in a factory but rather a comprehensive, complex system that needed to be kept in balance. For Steiner, it wasn’t just about the soil beneath our feet, but how everything impacted its health, from humans to the forces streaming from the moon, planets, and stars— in his words, “everything, everything is connected”. Steiner described manure’s ability to deliver nitrogen “astral” and its ability to carry oxygen as “ethereal”. These types of metaphors— which Steiner meant to be understood as literal, litter all of his works around agriculture. Humans, in contrast, represent an evolutionary advance beyond the astral level, a distinction that will later divide biodynamics from the deep ecology movement that rises fifty years later.

The farm itself was a living organism to Steiner— and that external inputs were simply a “remedy for a sick farm”. Within the political framework we outlined, this is unsurprising. And when it came down to specifics, Steiner was short— he found himself drawn to cosmic explanation rather than outlining what his form of biological farming looked like. He focused on preparations, like 500, and explained how plant reproduction relies on “Moon, Venus, and Mercury via the limestone nature” while the production of food relies on “Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and silica”.6

Other preparations were described as well— “502” involves placing yarrow in the bladder of a stag, exposing it to sunlight all summer, then burying it for the winter. Others included chamomile flowers in intestine, oak bark, valerian, and more with distinctive traits that were based in alchemy framed by cosmic forces. He recommended burning weed seeds in order to inhibit moon forces that accelerated weed growth, and more.

Unsurprisingly, a number of criticisms were justifiably leveled at his feet regarding his proposals— and Steiner’s response was simple. He was not interested in ‘going back’ to the past, but rather attempting to find new ways to do things that didn’t rely on linear, atomized systems, such as petrochemical fertilizers and pesticides.

By 1940 the concept of biodynamic farming had stretched four continents, thanks to a handful of dedicated followers from his eight lectures. Sixty of the 111 attendees to his lecture joined together to create the Agricultural Experimental Circle, which existed to experiment based on Steiner’s framework, to make the knowledge more publically available.7 Three of the main leaders were Count Keyserlingk, Rudolf von Koschützki, and Ernst Stegemann, who collectively oversaw nearly 8,000 hectares of farmlands.

Younger followers of Steiner were tasked with learning conventional solutions to the problems the farmers were solving, and their job was to “disprove materialism with its own weapons”. One of these researchers was Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, who would become the largest proponent of biodynamics in the 1930’s and into the 70’s.8

Concurrently with the explosion of biodynamics across the globe in response to petrochemical fertilizer was an increasing skepticism about conventional science, specifically regarding the justifiable concerns about the unintended consequences of new technologies. However, their concerns weren’t framed within the scope that conventional science didn’t have all of the information quite yet, but rather that the causes of problems were “etheric rather than physical”.

The ambiguity of Steiner’s positions allowed his work to be transmogrified as necessary. While the Nazis may have made an attempt on his life, the Green Wing of the Nazi party valued soil health as it tied directly to racial purity, and Steiner’s self-sustaining farms aligned with these values (it didn’t hurt that the international board for the Anthroposophical Society wrote a letter to Hitler saying Steiner wasn’t in relationship with “Jewish Circles” or that Steiner was of “pure Aryan heritage”). After Steiner’s death, internal struggles for leadership inevitably led to collaboration with Nazism by removing many ethnically Jewish, non-German, and antifascist members.9 While the occult pieces of Steiner’s work were distrusted, the values he provided to the Nazi party, plus their willingness to align themselves in disposition to the Nazis, outweighed their concern, and biodynamics was begrudgingly embraced, although it has continued to haunt the movement to this day.

Ehrenfried Pfeiffer’s writing didn’t help the movement’s image issue— Pfeiffer relied on the trope of the peasant farmer and the loss of “traditional culture”, and in 1938 wrote that it was up to Europe to create a “new culture” that could “perceive life and growth as an organic whole over the entire earth.”10 Pfeiffer’s book, unlike Steiner, provided a more practical application of biodynamics and dedicated a chapter to global farming practices, including highlighting the sustainable agriculture of China that was also highlighted by F.H. King and many of the permanent agriculture advocates in the United States during the same period. Pfeiffer’s book made biodynamics accessible and the global movement was able to spring to life.

Other writers like Viscount Lymington tapped into the pre-war anxieties in the UK through his book Famine in England, where he pointed to self-determination as a way to address fears of ‘communist takeover’, a “yellow race war or a Jehad”, or a continued increase of immigrants and the “scum of subhuman population”. In his words “healthy agriculture” was the antidote.11 Fundamentally, the solution to international fascism and communism was ultra-nationalism wrapped in anti-industrialist tropes, a common thread that continues to be exploited by several movements today. While Lymington was one of the more hostile voices for biodynamics, his words strike at a fundamental belief of many in the movement— that the efficacy of individual action motivated by ideals would trump consolidated power— albeit the State or business.

Biodynamics in the United States

The first person to use biodynamic preparations in the United States was Henry Hagens for his backyard garden in Princeton, New Jersey.12 Not far away, the Threefold Community was born in Spring Valley, New York, where a group of people were inspired by Steiner’s idea of a “Threefold Commonwealth” (which was interpreted as a libertarian alternative to ‘big government’). Immediately, they created a cooperative household (in their words, “as a first step toward an association of producers and consumers”), and followed with a vegetarian restaurant. Immediately after, they purchased a farm in Spring Valley in 1926.

As the biodynamic movement spread, it tied into people across the political spectrum— socialists, orthodox Christians, and people with esoteric spiritual beliefs. While we had talked about the role of the Nearings in spreading the homesteading gospel, Helen had previously dated theosophist Jiddu Krisnamurti, who had influenced her vegetarian and holistic view on food.13 Anarchists, alongside the Catholic Worker Movement and the Catholic Rural Life Conference, made agrarian settlements part of their programs, often tied to naturalist ideology that meshed with the biodynamic perspective.14

Enter J.I Rodale, the founder of Organic Farming & Gardening Magazine in 1942. While more focused on organics— which functionally was the same as biodynamics without the spiritual and celestial aspects— Rodale built his vision on the Rodale Orangic Gardening Experimental Farm in Emmaus, Pennsylvania, although the real profitability came from Rodale, Inc., a publishing enterprise. The first issue paired organic practices with “the Bio-Dynamic system and the Indore method”, a reference to Sir Albert Howard’s work, which is considered the origins of organic farming in the West. Pfeiffer was and remained a regular contributor, highlighting the overlaps of Rodale’s vision of organics and biodynamics.

In the magazine, the esoteric spirituality of Steiner was largely absent. Sprays such as Steiner’s preparations 500 through 508 were included by Pfeiffer, as well as proper composting, but little more about the relationship of the farm with the celestial world.

Decades later, the home of biodynamics would be formalized in Pennsylvania at an 830-acre experimental farm owned by H. Alarik Myrin & Mabel Pew Myrin. Mabel’s family owned the Sun Oil Company and her brothers were known publically as “American Fascists”.15 Mabel and her husband, a Swedish aristocrat named Alarik Myrin, also held extreme conservative values, and for undisclosed reasons, Alarik and Mabel were sent by her family to Argentina to manage a ranch. When they returned years later, they dedicated their lives to anthroposophic philanthropy.16

Their investments led to several biodynamic farms in the Pennsylvania region, some of which would develop training courses and tie into the Quakers, given Pennsylvania’s long history with more radical and pietist occultism. The courses, unlike Rodale’s magazine, leaned more heavily into biodynamics and anthroposophy as well as practical skills including botany, bookkeeping, agricultural history, and meteorology, and were expected to devote a significant amount of time to seasonal festivals, including even performing nativity plays each Christmas.17

Pfeiffer also released the Bio-dynamics Journal, which is still in publication today, and explores more about the spiritual aspects of biodynamics as well. The magazine also worked to reach across the aisle to the scientific community, attempting to pair their research with contemporary soil science to further legitimize their practices.

In the post-war years, new names sprung up to lead the movement, including Josephine Porter, a single mother from Pennsylvania, known as the “Milk Lady” because she would provide families with milk, whether or not they could pay. New issues sprung up and forced the movement to position itself politically as well. As increased populations raised new questions about sustainability, Pfeiffer wrote that there was not enough land to support the existing human population as it stood in 1949. In Pfeiffer’s words “Instead of asking ourselves whether there are too many people in the world, we are really forced to ask: Are there not too many people massed in some spots and not enough in others?”18

Behind Pfeiffer were several other key members of the Anthroposophic society with similar views who wrote extensively about collapse and population control. In contrast to the growing Deep Ecology movement that had sprung up in the 60s, the biodynamics movement argued that it was necessary to recognize the qualitative difference between humans and other living things. As the environmental movement concurrently picked up in the 1970s, biodynamics found itself trying to create its place between science, politics, and spirituality. At the same time, the rise of the Back to the Land movement sprung up and biodynamics was taken on as its framework for New Age spirituality and naturalism.

It’s necessary to distinguish, however, the leftist social movements of the 1960s with the New Age spirituality of the 1970s and how these impacted biodynamics. While many of the pre-1960s followers of biodynamics aligned more with the libertarian and agrarian right, the Back to the Land movement was largely driven by leftist urbanites looking to rekindle a relationship with nature.

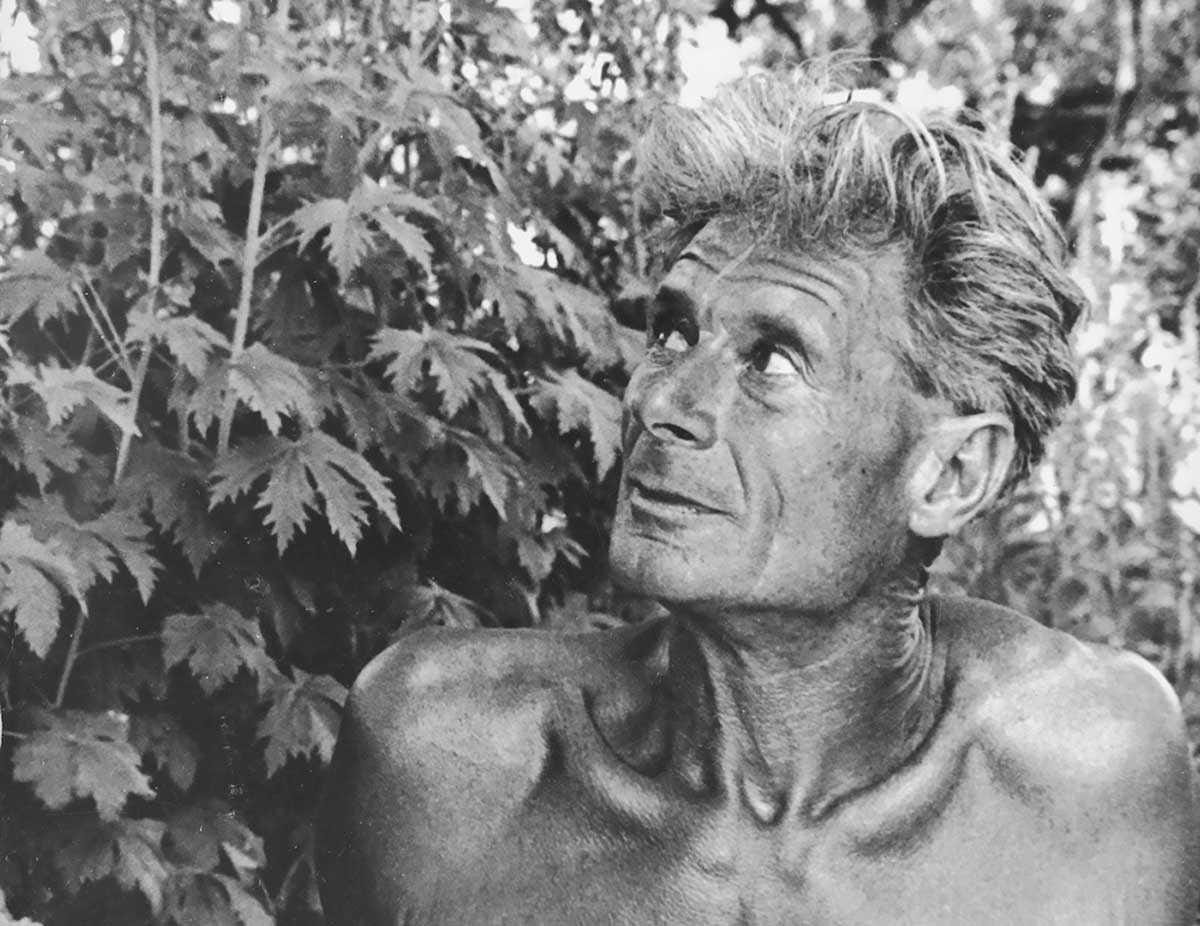

Several New Age founders were directly influenced by Steiner. Anthroposophic practices allowed people access to tools towards improving themselves in order to make a better world, while also satisfying their individual need for change and spirituality. The influx of Baby Boomers into the anthroposophic movement shifted how these beliefs translated into practice— instead of community improvement, spirituality was centered on self-improvement and self-actualization. Alan Chadwick was one of the voices capitalized on this shift— he was a translator who brought biodynamics into the New Age world and was often characterized as “anti-science”. Many of Chadwick’s students are leaders in the biodynamics movement today, including Sherry Wildfeuer and Stephen Decatur.

Other rising leaders of the 1970s had different translations of the biodynamics movement. Joseph Beuys, for example, applied Steiner’s economics from a strictly anti-capitalist position, describing the three principles “responsible for making the whole of a society sick… [were] Wage dependency, private ownership of the means of production, and profit as the driving force” and advocated for a guaranteed income.

Now, three generations from Steiner, his words don’t weigh heavily on the movement as they once did. Many rarely read Steiner. While Steiner looked to build bridges between modern science and “ancient wisdom”, many modern voices challenge modernity entirely. Part of this inconsistency stems from how biodynamics disagrees with the Deep Ecology movement which decenters humans, which underscores much of the environmental movement today.

Today the same issues exist within the movement— spirituality is loosely tied to Steiner’s work, which exists without a firm framework— and practitioners often operate as they wish, tying various spiritualities to the core biodynamic farming practices. This loose-fitting science and spirituality has kept biodynamics on the fringe— but where does the science stand today?

The Evidence

In 2013, the most thorough analysis of biodynamic preparations was done by Linda Chalker-Scott. While some of the newly incorporated ‘methods’ of biodynamics such as crop rotation, cover cropping, and polyculture show benefits for the soil, these are not unique to biodynamics. Many, if not all certification standards for biodynamics are no different from organic certification, except for the nine preparations demanded by Steiner (500-508). Chalker-Scott’s research highlighted the major studies in biodynamics; the consistent theme was that there were rarely significant improvements from biodynamic treatments compared to organics.

Studies showed no significant increases in microbial activity, zero increases in crop yields, and in some cases, organics outperformed biodynamics. In one study, organics outperformed biodynamics in mango qualities such as antioxidant activity. In one extensive study on vineyard performance under biodynamics, there was zero evidence of improvements in grape or grapevine health or quality, and the organically grown grapes produced more preferred wine than the biodynamically grown grapes. In another study, biodynamic preparations increased disease intensity in organically grown wheat.19

The point here is many biodynamic ideas are oversimplifications and extrapolations from ‘common sense’ ideas— for example, Steiner also advocated that germ theory wasn’t true, because germs were harder to understand than an easier to engage with the idea of cosmic forces. Waldorf Schools are modeled on Steiner’s beliefs around education, and many of them become the vector of disease outbreaks due to their low vaccination rates— in some cases as low as 15%. Steiner is a perfect example of the impacts of a cult of personality who take advantage of people’s distrust in the alienation created by capitalism and rely on using common sense to extrapolate answers for more complex concepts, often when those common sense ideas are wholly disconnected from where they’re being applied. For example, he argued that the lungs, mercury the element, and Mercury the planet were intrinsically tied together as part of his anthroposophic medicine beliefs.

The key point here is underscoring all of Steiner’s work is a radical self-interest that is predicated on self-preservation and hyper-individualism, which stands in opposition to all of human history. All of this is important when we look at the continued growth of pseudoscience, hyper-religiousness, and race supremacy that begins to permeate the Back to the Earth movement, as well as the other movements that rose up in the post World War 2 era including organics, permaculture, and an increasing white-supremacy led homesteader movement.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 16-page chapter, of (so far) a 1066-page book with 718 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. Second, you can listen to the audio version of this article in episode #210, of the Poor Proles Almanac wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Trauger M. Groh and Steven McFadden, Farms of Tomorrow Revisited: Community Supported Farms, Farm Supported Communities (Kimberton, PA: Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association, 1998)

“Announcement from the Experimental Group of Anthroposophical Agriculturists,” Anthroposophical Movement 4, no. 6 (February 6, 1927): 47.

Rudolf Steiner, “The Mystery of Golgotha,” in The Christian Mystery, trans. James Hindes and ed. Christopher Bamford GA 97 (Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1998), 48–58.

A. Usteri, “Factory, Forest and Farm,” Anthroposophical Movement 4, no. 40 (October 2, 1927): 213–14

Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, preface to Rudolf Steiner, “Agriculture Course.” Pfeiff er contributed this recollection to a German symposium that was published as “Rudolf Steiner, by His Pupils,” Golden Blade 10 (1958).

Steiner, “Agriculture Course,” lecture 1.

John Paull, “The Secrets of Koberwitz: The Diff usion of Rudolf Steiner’s Agriculture Course and the Founding of Biodynamic Agriculture,” Journal of Social Research & Policy 2, no. 1 (July 2011): 19–21; Herbert H. Koepf and Bodo von Plato, Die biologisch-dynamische Wirtschaftsweise im 20. Jahrhundert: Die Entwicklyngsgeschichte der biologisch-dynamischen Landwirtschaft (Dornach, Switzerland: Verlag am Goetheanum, 2001).

Alla Selawry, Ehrenfried Pfeiff er: A Pioneer in Spiritual Research and Practice: A Contribution to His Biography, trans. Joe Reuter (Spring Valley, NY: Mercury Press, 1992)

Peter Selg, Spiritual Resistance: Ita Wegman 1933–1935 (Great Barrington, MA: Steiner Books, 2014)

Ehrenfried Pfeiff er, Bio-Dynamic Farming and Gardening: Soil Fertility Renewal and Preservation, trans. Fred Heckel (London: Rudolf Steiner, 1938; New York: Anthroposophic Press, 1938).

Viscount Lymington, Famine in England (London: Witherby, 1938), 19, 42, 49, 52.

Evelyn Speiden Gregg, “The Early Days of Bio-Dynamics in America,” Bio-Dynamics 119 (Summer 1976): 27.

Jeff rey D. Marlett, Saving the Heartland: Catholic Missionaries in Rural America, 1920–1960 (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002).

Jeff rey D. Marlett, Saving the Heartland: Catholic Missionaries in Rural America, 1920–1960 (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002).

McKanan, D. (2018). Eco-alchemy: Anthroposophy and the history and future of Environmentalism. University of California Press.

Waldemar A. Nielsen, Golden Donors: A New Anatomy of the Great Foundations (Piscataway, NJ: Transaction, 2001), 168–76.

Evelyn Speiden Gregg, “The Early Years of Bio-Dynamics in America (Part II),” Bio-Dynamics 120 (Fall 1976): 7–18; Barnes, Into the Heart’s Land, 212.

Ehrenfried Pfeiff er, “Are There Too Many People in the World?”, Golden Blade 1 (1949): 31.

Chalker-Scott, L. (2013). The science behind biodynamic preparations: A literature review. HortTechnology, 23(6), 814–819. https://doi.org/10.21273/horttech.23.6.814