The current state of agriculture is untenable— driven by capital and full of unsustainable inputs, which destroy our ecosystems. Unfortunately, exploring alternatives to conventional agriculture is rife with greenwashing, misdirection, agendas driven by greed and cult of personalities. It’s difficult to understand and contextualize the history of agriculture, specifically permanent agriculture, regenerative agriculture, commodity crops, biodynamic farming, organics, and permaculture— not to mention the slew of other ethics involved in growing food.

The development of alternative agriculture movements are inevitably influenced by the world the farmers and organizers live in. There are tremendous demands placed on all of us as we all try and survive, and success within this system often requires abandoning personal principles. We normally use historical context to help us explain why and how movements grew, failed, or succeeded, but we often fall short of taking this same historical context when looking at our food systems and how they should develop into the future.

Agroecology, the word

We all use language to describe the world and arrange our thoughts, and that language changes as cultures shift. Every word has buried within it a myriad of social factors and influences.

Social movement-based terminology itself often is echoed into broader conversations and in this normalization, slowly dilutes itself. When any term becomes popularized or critiqued (such as organic or regenerative when speaking of agriculture), its application becomes less and less meaningful. Instead they are increasingly defined by how those terms react or exist in relation to their alternatives.

For example, if we understand organic practices, how does it influence our understanding of the term ‘regenerative’ within agriculture? Many view regenerative as something ‘beyond’ organic simply by its proximate relationship to organic, right? This unconscious mental model ties regenerative and organic together as linear points along a single axis. These linguistic inter-assocations can be both useful and damaging; the depth of language around terms adds a foundation which becomes more rigid and less fluid in an evolving world. A term no longer describes a simple idea— it describes a condition which exists in opposition to other terms.

That doesn’t mean terminology isn’t slippery and difficult to engage with critically (as we see in discussing permaculture), but rather understanding how language operates to help us point to when and how the development and application of new terminology is more appropriate than simply attempting to restructure how a term is applied (think: decolonize ‘X’).

New words and language allow us to start fresh, which is both a liberatory process for those seeking to fashion a new path forward but also comes with the added complexity of developing a new language into a greater dialogue. Some practitioners of the alternative agricultural models described above attempt to claim and co-opt “agroecology” as simply a different word to describe the same thing (or a specific form of x) they are already doing, this makes assumptions about agroecology that are incorrect, erase agroecology’s history in the Global South, and further deny this movement any of its agency in forging its own space in these dialogues.

Over the past few years, the development of the term “agroecology” has gained steam here in the United States, despite having been a core component of the La Via Campesina (among others, see our pieces on Erna Bennett, Efraím Hernández, and A Green Revolution for Africa for examples) movements across the Global South. ‘Agroecology’ as a word is loaded with different meanings in these places where it is practiced. As a nascent term, this fluid application of agroecology inevitably means that the application and understanding are understood within the context of what it is not— in academic settings, for example, it often is in relation to agricultural technology (and Traditional Ecological Knowledge— or TEK).

Further, within the context of the global south, this term is underscored by a very political component— which is inexorably tied to the active speaker. While many socialist, communist, and anarchist movements will paint this political framework explicitly, the reality is much more nuanced— something we will dive into in a moment. This complexity of definition is in itself part of the terminology finding its own space in relation to the movements around it while absorbing the interests of its biggest advocates. It’s because of this complexity and diversity I felt it would be meaningful to unpack the word ‘agroecology’ in a way that aligns with the work we’re doing, and how I feel the term would be most effectively understood and applied.

While I think it’s worth treating agroecology as a relatively modern term, given its newness in contemporary agricultural circles, there is a historical context for the term— in fact, multiple. Before the term was coined, one of the first folks who spoke about resilient indigenous agricultural strategies was Franklin Hiram King at the beginning of the 20th century. In the following decades, people interested in sustainable agriculture from a number of different fields came to find the same term— from the Russian Bensin who first used the term “agroecology” in 1930, to the German ecologist and zoologist Wolfgang Tischler who published the first book titled “Agroecology” in 1965. The first major figure to fully describe agroecology in the United States, even if he hadn’t used the term, was agronomist Karl Klages in 1928.

What had initially started in the early 20th century was understanding agriculture with an ecological context, following the same rules as ‘wild’ landscapes, evolved alongside other similar disciplines such as the organic movement, the biodynamic movement, the syntropic movement, and the permaculture movement, all of which overlap in some facet or another. However, during the 1980s, writers and researchers were recognizing the inherently interdisciplinary framework of agroecology and the role of other knowledge systems to help understand local agricultural communities. Much like Russell Lord had proclaimed fifty years prior, environmental problems were the byproduct of social problems.

But what changed, in particular, between permaculture and agroecology in the late 1970s and early 1980s?

As disciplines from ecology to sociology, anthropology, and more offered insight into the “other knowledge systems” which continued to mature and play prominent roles in alternative agricultural circles, the politics of agroecology became a larger driver in how the movement was viewed. This was in part because it had gained a foothold in Latin America, as hundreds of NGOs and indigenous resistance movements challenged the Green Revolution and its ecological and social consequences. The Green Revolution provided credit access and new technologies to rich farmers— increasingly leaving poor farmers behind with more debt and only occasional success stories. This led those farmers to push for a bottom-up approach, specifically utilizing the resources and indigenous knowledge they already had available.

The grassroots participatory aspect of agroecology and its chief concerns with the needs of the most marginalized allowed for it to catch fire across the region.1 TEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge) is inherently knowledge-intensive and hyperlocalized; its practices must be developed on local knowledge and experimentation making it by definition based in the hands of the people on the ground, and incapable of being delivered as a top-down approach. By definition, the framework of agroecology is anti-hierarchical.

Interdisciplinary researchers concerned with the impacts of the Green Revolution on these poor communities advocated to develop new approaches for working with traditional farmers who could draw from endless wells of very specific farming knowledge, and that the path to give those farmers the capacity to live dignified lives must begin with their ancestral knowledge.2 Agroecology’s maturation was at the right place at the right time. The failures of the Green Revolution, the rise in populist politics, and the emergence of anti-American sentiment in the throes of the Cold War gave agroecology a central place in the resistance movements of peasant and indigenous people.3 Activists, peasant farmers, and specialists developed fluid iterative processes to find ways to develop appropriate technologies that met the needs of the landscape around them. The practices they developed and refined worked in conjunction with nature to build a complex system— and this methodology soon became the core of agroecology.4

The modern left and its influencer base’s interpretation of Agroecology doesn’t consider the specificity and depth of this originating moment. Colonization cast both a shadow on relations with the land and State and scars from physical violence on the landscape and its people that is far more difficult to untangle than a handful of slides on Instagram can portray. In this same vein, the left has liberally translated this rural block and its relationship to agroecology both in alignment and outside of the modern left’s interpretation of the movement. Projects like La Via Campesina, which sprung up in the foothills of agroecology are now framed as being completely leftist movements. For many Campesinas, these agroecology-based systems are a matter of self-survival and the only way to retain autonomy. While undoubtedly the agroecological movement is based in rural politics, the politics are less “political” and more material for those involved. For many, peasant farming isn’t an act of resistance, but rather a clinging to what can stand up in the face of shaky national politics and nefarious global actors in regions like Latin America, particularly in the 1980s.

That said, the explicit politics of class and specifically the rural class are a fundamental piece of how agroecology continued to evolve, in tandem with the corresponding ‘re-peasantization’ which took place over the following decades.5

In the book “Agroecology: Science & Politics”, Peter Rosset & Miguel Altieri define agroecology as:

“the science that studies and attempts to explain the functioning of agroecosystems, primarily concerned with biological, biophysical, ecological, social, cultural, economic & political mechanisms, functions, relationships and design; as a set of practices that permit farming in a more sustainably way, without using dangerous chemicals; and as a movement that seeks to make farming more ecologically sustainable and more socially just.”6

This definition helps us understand the multifaceted nature of agroecology as both a vision and a method. It also calls our attention to the greenwashing happening in much of its application today, from the United States gagging the FAO (The Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) from talking about agroecology’s politics and trade policy implications, and more.7

Without a political framework, agroecology cannot address the fundamental, systemic exploitation embedded in our existing foodways. While remaining ‘apolitical’ makes the movement more palatable (and this is something I disagree with, which we’ll dive into shortly), it doesn’t challenge the system as it exists today but rather provides new tools to make our failing system fail less.

A few months after the FAO event which disallowed any discussion of the politics behind agroecology, a counter event took place in West Africa to develop a shared vision of agroecology. The organizers sought to build a definition for the movement outside of the power center of the Global North whose language erased the inherent politics of the movement.8 At this counter event, the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty presented a vision that was explicitly political and advocated for transforming the world and food systems outside of the industrial food production model. Again, what should be becoming clearer is that defining agroecology, much like other movements, is often best done by defining what they are not.

The Origins of Agroecology

It’s unsurprising that agroecology’s center of gravity is in the Global South; today it is best known as a reflection of indigenous and peasant agriculture. While I believe this tends to flatten the lived experiences and the complexities of why these regions of the world cling to small-scale ‘peasant’ & ‘campesino’ farming practices (hint: it’s safer for food to be closely held in places which have been destabilized by outside actors than to build bigger systems of collaboration), this is outside of the scope of what we are hoping to do here.

However, the Global South provides a lens that we can use to start unpacking what agroecology is, instead of simply pointing to what it is not. The centering of Indigenous & peasant/campesino practices in these regions highlights the role of ecology in providing the basis for their food systems. By examining this, we have a base point to begin developing our definition of agroecology.

From the grains collected in Eastern Europe by Erna Bennett to the corn harvested by Efraím Hernández across Central America, the genetic diversity and nuanced, locally adapted food systems offer tools to sustainably and ethically survive a diversity of environments that is otherwise impossible without massive, unsustainable inputs. Genetically diverse, ecologically-aligned food systems have developed across the globe in innumerable ways in reflection of the vast diversity of the planet. The resilience of naturally diverse communities offers a unique benefit to tackle the challenges of increasingly irregular weather patterns and rapidly changing climate, and leveraging these as food systems offer benefits to which no other agricultural system can compare.

These systems have only recently begun to be viewed not as artifacts of time but rather as promising exemplars for the creativity of humanity to adapt to a diverse set of climates, whether it be the Milpa systems of the Maya or the transhumance dehesa farmers of the Iberian peninsula, both of which produce exuberant quantities of food in what would be considered inhospitable conditions by conventional agriculture.

Academic interest in TEK, that is, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, has accelerated over the past few decades as well. TEK is a term used to describe the indigenous knowledge systems about soils, plants, and material surplus for creating sustainable human communities in alignment with ecological conditions. These lifestyles are based and reflect the complex & fluid ecological models that exist in their respective communities, reflecting a need to intimately understand the mechanisms at work in these ecologies.

Returning to the peasant agriculture image portrayed by academics and NGOs— while TEK does often fit the image of the singular farmer in small communities, sun-beaten and aged, this is only a small facet of what is agroecology. While TEK offers insight and depth in elegant practices, the aims of agroecology seek to utilize indigenous knowledge systems with modern ecological and agricultural science. In a world of either/or, agroecology provides a third path, seeking to apply the best of all worlds. Integrating the best of each of these systems, including appropriate technologies, we are capable of building efficient, scalable systems which demand less from us in terms of production while maximizing ecological and human benefits. Our goal is NOT to return or to glorify peasant farming; it is to build the best possible systems for the best possible conditions for people to engage with the world in the ways which they are best suited.

Defining Agroecology

So what are the components which become key principles of agroecology? From there we can unpack how these function and the tools we need to fully and effectively engage with the landscape in an agroecological way.

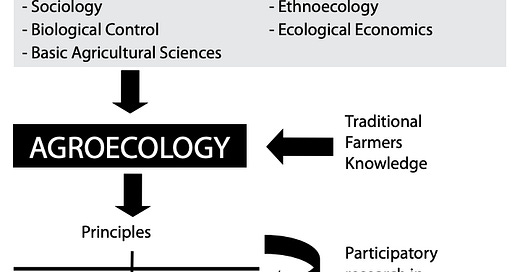

Agroecology often defines itself as bottom-up learning, and by looking at the bottom and going up through this graph, we can see that this system is an iterative process that begins with farmer experience stewarding land-based and water-based crops, as well as a managing a diversity of animal relationship types and collaborative efforts. Over generations, these localized relationships become apparent as species diversify into local ecotypes. This is true for both domesticated and undomesticated human-managed species from maize to honey locusts.

Trying to narrow down terms for systems that are inherently unique to specific conditions can be a difficult task, but Rosset & Altieri identify six features that are exhibited in most traditional agroecosystems:

high levels of biodiversity, which plays a key role (my emphasis) in regulating ecosystem functioning and also in providing ecosystem services of local and global significance;

ingenious landscape, land, and water resource management and conservation systems that are used to improve the efficiency of agroecosystems;

diversified agricultural systems that provide a broad variety of products to local and national food sovereignty and livelihood security;

agroecosystems that exhibit resiliency and robustness to cope with disturbance and change (human & environmental) minimizing risk in the face of variability and stochasticity;

agroecosystems nurtured by traditional knowledge systems featuring many farmer innovations and technologies; and

strong cultural values and collective forms of social organization, including customary institutions for agroecological management, normative arrangements for resource access and benefit sharing, value systems, rituals, etc.

When we start to unpack these features, we are able to see how each fact is framed on localization—both in localized biodiversity and localized practices. In the process of forging these localizations, the farmer’s innovations and technologies are based on - rather than intended to disrupt - the ecology they’re based in. For example, improvement in water management in an agroecological context improves local biodiversity while not seeking to fundamentally transform the ecological system itself. The diverse species in agricultural systems fit into the ecological context, improving regional biodiversity. The goal is not to green the desert but to live in harmony with and nourish the delicate arid landscape.

These practices are not simply moralist but have concrete benefits to farmers and landscapes. Diversity-championing strategies increase system redundancy by enabling numerous generalist and specialist species to overlap. Redundant systems can withstand greater pressures from factors such as climate change, invasive species, and global biodiversity collapse. Moreover, a single crop failure need not impact the entire function or output of a biodiverse farm - the diversity of yields enables difficult years to be weathered without collapsing.

Adapting practices to local site conditions - down to very specific microclimates in different areas of a single site - creates habitats for ecology while also maximizing the productivity of the system. For example, if inputs are varied between a low nitrogen upland meadow, a wet boggy field, a stream bank, and a fertile bottomland, they can increase the unique biodiversity of each site - reaping the benefits of ecosystem services (like pollination and pest control) - while avoiding wasting energy fighting a system poorly adapted to a selected practice. This means more food, fewer inputs, and less effort by the farmer.

Fundamentally the framework of agroecology is imperfectly local and place-based. Community, both human and non-human, collectively work to keep the system healthy and resilient.

To synthesize the above points, we can describe Agroecology as a system which:

Supports meaningful above-ground biodiversity

Uses diversity to manage pests and disease

Facilitates healthy diverse soil biomes

Recenters traditional foodways that are derived from landscapes

The Data & Its Complications

While there’s an extensive amount of data to unpack about the benefits of intercropping, polycropping, building systems with ecosystem benefits for pollinators, and so on, I don’t think these are areas that people reading this would need further information on. These systems offer great potential as we learn how we can scale systems and take advantage of their benefits while maximizing our capacity to leverage appropriate technologies.

NGOs and other vested parties tend to highlight that 70-80 percent of the world’s food is grown by small-scale food producers in plots averaging 2 hectares in size, that there are over 1.5 billion of these smallholders across the globe, how we view agriculture here in the Global North doesn’t represent how people relate to food systems across much of the world.9 This can be insightful but can also color the vision of what ethical land stewardship must mean. While collaborative efforts take place on these farms and they exist as part of complex communities, the stewardship of landscapes is irrevocably individualist within a matrix of community. Individual farmers are interested in managing their individual land, with community involvement but not necessarily in a communal, collaborative, or scalable manner.10

The question of scalability is often perceived as an inverse relation to both autonomy and anti-hierarchical structures— with centralized polluting commercial agriculture pitted against sustainable family farms, but I think agroecology can point to a third way that doesn’t befall the trappings of glorifying unnecessary hard, intensive farming practices. We can recognize what peasant farming provides in the real world while also recognizing that we can (and must) offer a better alternative. This can be done utilizing appropriate technologies which can not just free individuals and communities from their smallholdings (which in many cases make up more than 50% of the workforce and even children) but can help further push for greater interdependence across regions, leveraging our collective resources for the greater benefit of all of us, allowing children to study and explore while adults freed from toil can find different ways to engage with the human and non-human world, fulfilling their needs as humans.

What does it look like to create polycropping systems that can effectively become automated in some capacity? Frustratingly, there’s no guidebook and few examples. Agroecology is both very specific and inherently incapable of being defined on a large scale— it is not prescriptive and the technologies associated with it likely will not be either. We can still, however, imagine potential mechanisms to apply agroecological thinking to the domain of automation.

Much of the flash of the agroecological movement is embedded in data— improvements in measurable standards of living, biodiversity metrics, yield & profit, and a vague notion of “empowering communities” which are all important and valuable clues as to what agroecology can offer (and what has drawn interest from a global audience, in comparison to permaculture.

Africa’s agroecology movement over the past few decades in response to A Green Revolution for Africa (AGRA) has been a rallying point for the movement, pointing to increased yields by 50-100 percent, improved and varied diets and nutrition for local communities, as well as the obvious long-term benefits of healthier soil, water, and so on.11 Farmers in these systems claim to have better food security and better health.12

Similar to the Latin American model discussed prior, African farmers practicing agroecology are typically smallholders who operate on 2 hectares or less. This invariably operates similarly to homestead-esque projects we are familiar with in the Global North, and due to limited resources typically require community support and solidarity. As global climate change, ecological destruction, forced displacement, and colonial atrocities continue to bear down on these small farmers - they carve out systems of autonomous self-determination through their agricultural practices, which result in improved lives for all in their communities. Within the tug-of-war that is scalability and individual autonomy, colonization, and ecological destruction has afforded individual autonomy some sense of self-control in the face of overwhelming horror and displacement at the cost of improved lives for all.

Some researchers argue that when all outputs are fully accounted for, small-scale agroecological projects are just, if not more efficient than large-scale projects. On this, I have my doubts.13 The efficiency of small farms cannot be denied in unique challenging landscapes, where bespoke practices cannot be scaled up or applied elsewhere. But medium to large-scale systems are comparatively unexplored in an agroecological context. And while massive amounts of investment in tool design and development exist for small-scale farming/homesteading (just check out YouTube), scaleable equipment for medium-sized farming in these types of unique systems is entirely lacking and offers great potential in improving productivity at this scale.14

Again, this doesn’t mean to discount the efforts that have taken place across the globe in the name of agroecology. These achievements are measurable and impactful. Rather, we can follow through with Agroecology’s participatory self-feedback systems of development and improvement to the novel context of global north foodways and improved scalability. Our economic and ecological systems today are driven by petrochemical agriculture focused on annual crops (something I have coined the “gastropocene”), we can use systems developed in small-scale agroecological models and apply them to novel conditions - transforming our foodways and denying the artificial borders between agriculture, society, and ecology. How do we create collective, community food systems which don’t require that individuals must devote themselves to small plots of land, but rather an integrated system designed for specific ecological regions?

While there’s no template, and there will surely be failures, being willing to risk those failures is our first step in moving away from hyper-individualistic plots, which feeds into the homesteader mentality which permeates much of American & European “Back to the Land” culture.

In 1935, in response to the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, Roosevelt’s resettlement act under the New Deal moved people out of struggling rural and urban areas into small planned communities. The idea was to create a community network of homesteads supported by small industrial downtowns. Ideally, this would create a community of individuals able to produce much of their own food and goods without sacrificing their American hyper-individualism. The fact these do not exist today speaks to their failures.

Communities allotted 40 or more acres to each person in some instances, all of which were experienced farmers, only to have communities rapidly fall apart.15 This insight into American homesteader culture should give pause to this idea of interconnected homesteads being a viable model here in the United States, and it points to the complexities of growing food on a small scale in regions that doesn’t have cultural and ancestral knowledge.

Conversely, folks today are working to find alternatives for medium to large-scale agricultural projects, from the work of Chris Newman at Sylvanaqua Farms in Virginia to Feed the People Farms in Georgia to Andhra Pradesh’s Natural Farming Movement Womens’ Collectives in India.16 The most successful examples so far have all emerged from the Global South, where farmers continue to develop and push the boundaries of what was considered possible. For example, a 1100+ hectare restoration project in Cajamarca, which doubled incomes for farmers through agroecological practices and restorative projects, showcasing the benefits of TEK in unique regions.17 None of these models will be an answer for everyone, nor does it even mean they will be successful on any meaningful scale— that’s not really the point. Instead, they highlight an emerging answer to the most difficult problem of our era— how can we begin the process of building alternatives to both industrial agriculture as it exists today that is not rooted in self-sufficiency but rather community ownership, cooperation, and the toleration of the uncomfortable ebb and flow inherent in building any new way of living?

An example that highlights these challenges is the organopanicos of Cuba(problematic as it might be for a number of reasons that we won’t get into here), specifically around integrated crop-livestock farming systems. Leveraging these systems allowed for labor needs to drop nearly to half within 3 years of production, allowing each hectare of this system to feed nearly 5 people at the cost of around 800 hours of labor— which is about 6 months of labor18 This yield to labor ratio is drastically higher than conventional peasant farming, but it’s worth contextualizing this figure— the average American farmer, through mechanization, can produce an equivalent amount of calories in about 25 hours.19 That’s less than .4% of the time to grow the same amount of food, a massive difference which is difficult to even imagine.

Of course, there’s the obvious qualifier of petrochemical inputs and their corresponding yield improvements, but it’s worth considering how an increase of labor 32-fold fundamentally changes our labor relations with agriculture, and that’s not accounting for the fact that Cuba has a uniquely advantageous climate for food production in comparison with much of North America. The unique agricultural conditions here in the United States presuppose a wild restructuring of labor resources that would be hard to stomach for most Americans, despite their curated homestead social media feed.

The takeaway here is that the future won’t have a simple fix, and the solutions we are developing today are by no means complete solutions, but rather what will be archaic remains for future generations, a necessary step along the road to something better.

A New Agroecology

I started this piece talking about language, the evolution of terminology, and why and when it’s appropriate to think about creating and defining new language, and I’m ending it in that same vein. My own personal vision of agroecology is different than much of the agroecology taking place across the globe. Agroecology as defined so far has centered Indigenous knowledge, TEK, historical conditions (both for the landscape & the people), social injustices, and bottom-up organizing. All of these are important and valid and necessary.

However, in the examples above of the successes of agroecology, much of those successes were framed around crop production— and heavily non-native and historically culturally irrelevant crops such as maize farming, for example, in Africa. There’s obviously nothing wrong with growing non-native, non-invasive species for specific purposes, but centering non-native crops in a system predicated on things like TEK does seem a bit out of place, and thus asks us to consider how we are defining and relating to TEK and the landscape.

Further, it’s worth considering the complications explored in my criticism of the glorification and fetishization of peasant farming— the histories we value and validate offer insight into ourselves. How do we understand and translate agroecology into a viable system that doesn’t trap us within the past?

Further, agroecology as it has been applied in most of the rural, Global South has been effective at increasing the quality of life for the poorest communities in the world, but the gap between this standard of living and what we experience in, say, middle-class America is still incredibly wide. The question for us here in the belly of the proverbial beast isn’t to critique how agroecology is applied in places that are worlds away from our standards of living, but rather to come to terms with its limitations and to consider what our future here looks like.

We have to wonder what places like the United States look like in the face of a world where petrochemical fertilizers will no longer be available at present levels— whether due to the energy inputs to create said chemicals or simply because of the limits of available resources to be mined.20 There’s no shortage of evidence that our ecological systems, at least here in the United States, are quickly unraveling and have been doing so for some time. What do solutions for this actually look like, and how is it shaped by our diets and lifestyle choices?

Anti-Homestead Agroecology

Despite the advocacy by many, if not most of the regenerative agriculture, permaculture, and whatever other flavor of alternative agriculture movements leaders, growing your own food is not the solution to the multiple crises at hand. In fact, in some cases, it is potentially exacerbating the issues that face our soils, our waterways, and our health. That’s not to say you shouldn’t grow food if you enjoy it but rather to reframe the idea of what it means to engage with our landscape. Instead of considering ‘reducing’ our footprint, we should alternatively be considering where we step— how our decisions can align with the landscapes around us using the lens of agroecology.

Growing tomatoes, for example, can be enjoyable for the right person, but will likely require inputs— even if not fertilizer— the resources for composting, the fenceposts to keep rabbits away, and all of the other forgotten material expenses which make growing tomatoes possible. We need to recognize the true costs of growing foods and how that changes our relationship with the landscape around us. Growing a tomato plant, biologically speaking, is no more or less significant for the native flora and fauna of my region than growing any varieties of non-native grasses. This means that growing your own food can still be an anthropocentric process which doesn’t give back meaningfully to the ecology around you in any way. Moreover, it’s a wildly inefficient way to grow food and almost never addresses our needs of staple crops (who’s growing primarily wheat & corn in their backyard?). This is not to say you should not grow tomatoes, or produce your own food. Rather, we should be interrogating the quality of our relationship with land, and both the costs and benefits of our decisions.

Homesteading is an isolating process that requires individual despecialization (you need to know a little bit of everything) and redundancy (even in ‘communities’ of homesteaders, everyone is fundamentally doing the same thing, more or less). The homestead landowners carve up fluid landscapes into privatized parcels with different management practices, each one alienated yet impacted by their neighbors. We could spend extensive amounts of time breaking down the issues of homesteading, and this again isn’t to say that you should stop doing activities you enjoy but rather to contextualize homesteading as properties of human alienation and hyper-individuality and not a revolutionary solution to the problems of modern industrial agriculture.

If we seek a better agroecological model than homesteading in the Global North, it must combat these structural flaws - alienation, disconnection from land, unnecessary redundancy, and anthropocentrism. What would that look like?

Consider what a farm would look like if the crop selection process began not with farmer preference, but with native ecological conditions. Rather than turning to familiar euro-centric foodways defined by heterogeneous plants, the farmer would start with what the land needed to express its character.

Here in the northeast, a wetland would direct decisions towards wild rice, tuckahoe, hopniss, cattail, paw paw, black walnut, and supplementary sedges which define such landscapes. The farmer would focus on reducing heavy machinery to avoid soil compaction, reduce the use of fire in land management, and avoid applying dams to the waterway. Fishing and waterfowl hunting would be an excellent addition to yields in these conditions.

Meanwhile, a wooded area might suggest a management style that leans towards savannah conditions, with native masting trees and shrubs, surrounded by native grasses and wildflowers. The farmer would likely use fire to manage these openings and could plant numerous traditional field crops such as three sisters and sunflowers in polycrop management systems.

In all of these cases, the farmers must seek ways to automate these systems to increase productivity and avoid toil, without sacrificing the inherent spirit of the land. Prior to industrialization, this was done through landscape-wide practices such as burning, flooding, and grazing, along with shared mechanization like mills. We can learn from these methods by identifying appropriate place-based labor-saving technologies (a watermill cannot exist in the desert) and organizing our landscape to enable these technologies to be fully leveraged. In a forested area for example, a community might seek to develop a series of interconnected nut orchards with shared machinery (with trees spaced widely enough for the machinery to access) and seasonal cooperative burns to keep the landscape open. These orchards might allow livestock to graze in a modified form of pastoralism, and have hunters cull overpopulated deer and share the meat collectively alongside the produce from the orchards.

By starting with landscape and then interrogating how humans can co-exist and find a yield in those systems, we can ensure that ecosystem services are preserved and the ecology protected. Moreover, it helps us reconnect to the non-human world and develop a deep appreciation for the systems we are wrapped within. These systems - inherently diverse and place-based - provide resilient systems which can withstand the pressures bearing down on us.

As we regain our footing in our local ecosystem, the question of what future novel ecologies and food systems look like undoubtedly arises. Ultimately the solutions will have to be pragmatic, but they need to begin with a principled framework that we develop beforehand.

Scaling Up Agroecology

Intuitively, the idea of scaling up agroecology can seem a bit problematic; how can something without any power structure grow? How does a leaderless movement expand and build bigger projects? The inherently political bent of agroecology makes this harder. How can you quantify the impacts of a system which is framed and dependent on local conditions, both biotic, abiotic, and historical, forcing bottom-up leadership led by farmers to account for the diversity of contexts? Spread of innovation is, again, not driven by leaders in a movement, but rather horizontal communication, a process termed CAC within the agroecological movement, or Campesino a campesino, in which innovations from farmers use “popular education” to share them, using their own farms as their classrooms.21 As we saw with the Green Revolution in Mexico, farmers are far more likely to listen to other farmers rather than agronomists who have no depth of local knowledge and practices. This process empowers farmers and reflects local needs and culture, rather than some abstract overarching goal.

CAC is a demonstrably effective method to spread agroecological practices outside of Latin America as well as Andhra Pradesh and the Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha (KRRS) which focus their efforts around Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) through self-organizing at local levels without any formal movement or paid staff (although some figures through formal peripheral organizations such as organic movements and farmers unions).22 ZBNF is a modern interpretation of Vrikshayurveda, an ancient land stewardship method in much of modern India, reflecting cultural values, norms, and historical context while embracing modern scientific evidence. The movement across Andhra Pradesh is arguably the most successful globally, millions of farmers across India are practicing ZBNF and agroecology, primarily utilizing biostimulants and restoring landscapes that reflect traditional tree crops that had once been prominent on the landscape prior to colonization.

KRRS’s women-led cooperative models for education are central to its success - shifting dynamics around education and challenging patriarchal structure within communities. This drives a community-led process to allow farmers to be open to social pressures to change their practices, including those which perpetuate inequality.

Communities are the engine of Agroecology. Nature doesn’t honor property lines, and a bountiful ecosystem provides for its stewards. Communities can identify and adopt practices which foster their sovereignty and wellbeing - such as land management, financial investments, and resource allocation - pushing even the most recalcitrant of their farmers to join the larger effort. As the benefits compound into greater and greater results, the community can learn from and celebrate the results together - further refining what works in their local conditions.

This also means changing values around what food looks like. Specifically, local and regional markets need a marketplace willing to center regionally-appropriate products for farmers to grow at profit.23 This can be done through education, community-supported agriculture schemes, and favorable public policies.24 And of course, this requires an honest look at the food culture that exists where we live today. Our food culture is non-existent; few regional delicacies exist, and our diet here in New England has little to differentiate it from most of the United States. If we want to be in tune with the land, we need to be producing and eating foods appropriate to our local conditions, while not ignoring the resources and developments made to improve our capacity to grow food at the same time.

Again, the agroecology movement is inherently a social and political movement, because without building political infrastructure, supporting farmers and their new products in already politically-bent markets is setting farmers up for failure. The dilemma, of course, with relying on political influence is that farmers engage with politics in a way that forces them to continuously risk their livelihood based on political power, as was experienced in Brazil after the 2016 parliamentary coup d’etat, where many of the policies which allowed co-ops to thrive were reversed, destabilizing many farmers who had relied on them.25

The Politics of Agroecology

We keep mentioning the inherently political nature of agroecologyand it’s worth exploring this line of thinking outside of the continuum of American political thought.

Agroecology, as we have said, is inherently political, and yet many institutions working to incorporate the ecological side of agroecology have downplayed its political aspects. The intent of these organizations is to plug in the technical aspects of agroecology without addressing either the cultural or political dynamics of the movement. But what is the politics of the agroecological movement?

The reality is that the politics of agroecology cover a wide scope— while anti-capitalism underscores the movement, more specifically anti-colonialism— the specifics of the movement are simple— a defense of the laboring class of farmers.

Anarchists, communists, and socialists of all stripes tend to paint the anti-capitalist framework of formal institutions backing agroecology (like La Via Campesina) as full-throated support for the anti-capitalism, but in the process of doing so ignore the dynamics at play. These institutions empower disenfranchised and vulnerable peasant farmers, who themselves have living memories of violent displacement and wholesale destruction under colonialism. Food sovereignty and sovereignty for their friends and family— their community— take precedence over their alignment within any leftist movement. A cooperative-model economy that allowed for private capitalist enterprise would be readily more accepted by many in these movements, despite these same people being heralded as proof of a bubbling revolution happening on the periphery of urban spaces.

Instead, I would posit that reframing politics within a class framework makes far more sense, and reflects the real values of many of the farmers supported and involved with cooperative projects across the Global South. Reframing this dialogue in such a way takes the central movement away from inter-ideological disputes led by hyper-political figures and instead, it returns the power back to these communities of workers in any fashion they desire, as long as they can claim their individual and collective autonomy.

This is a worthwhile lesson here in the United States and one that’s worth considering in a nation where the rural/urban political divide is much more extreme, despite the fact that working-class rural folks in the United States often support progressive labor policies (and in some cases even more than ‘liberal’ urbanites).26 This is a topic worth exploring in-depth, and one that I won’t waste any more time navel-gazing about without the space to explore in more depth. Functionally, what we don’t need is more academic bloviating or influencers forcing unrealistic dogma, and what we do want is more on the ground and people willing to work through the discomfort of building trust and finding common ground.

The times require us to adopt a non-dogmatic bent, but we also cannot ignore the role of justice in a movement based in ecological sovereignty. Agroecology requires restorative justice for indigenous people & non-humans across the globe who have been forcibly removed from their homes and/or their cultural traditions. While contemporary agroecology texts don’t address this in significant depth, the answer that emerges is simpler and more beautiful in many ways— empowering communities to make their own decisions about what that restorative justice looks like. Again, this makes agroecology incompatible with industrial agriculture, as industrial agriculture views the diversity of traits of an ecosystem as issues to be addressed and things worth celebrating, despite greenwashing attempts by various governments, agribusinesses, and NGOs.

Here, in the United States, of course, this is a bit more complicated. With over 99% of their lands lost, Indigenous people would face an impossible battle in attempting to restore their prior relationship with Turtle Island.27 Fights for Land Back are important and extremely valuable for a number of reasons, and their hard-fought victories are worth celebrating, but it’s worth considering what can be done to fit these unique circumstances into this complex and uncomfortable narrative.

While it’s easy as white people to push for Land Back and decolonization, pointing to how much of the world’s diversity is protected by indigenous communities, it erases any responsibility of colonizers and their beneficiaries to solve the problems created by industrial agriculture and indigenous displacement— specifically climate change and ecosystem collapse (read Jay Lesoliel’s piece on this subject here for a more in-depth analysis).

Building deep relations with the non-human world around us in the face of colonialism is painful, for both indigenous and non-indigenous people The more difficult challenge is to assign measurable targets for restorative processes and to figure out what that restorative process looks like for people with access to resources.

What does that look like? I’m not going to suggest I have an answer for that. But I do think there are some basics that should help guide what restorative agroecology looks like.

Feeding working-class people affordable, high-quality food.

Improving and incorporating local ecology, and traditional land stewardship practices, as well as intentionally engaging with indigenous people who are interested in rekindling (or building upon) a relationship with the landscape.

Building community-led, decentralized systems of food production.

Co-creating & sharing knowledge regardless of profit.

Restoring place-based food systems in alignment with market interest.

Recognize the needs of local ecology, the sovereignty of native species and their rights to exist in full vibrancy in the lands and waters they call home.

Work thoughtfully and sit through decisions slowly and collectively.

Consider climate change in your management decisions and make space for non-human climate refugees without sacrificing native ecosystems.

Build accessible systems from the start - soliciting input from interested parties on how to remove barriers (or never impose them, to begin with). Food and ecology are for all people and stewarded by all people, in different ways.

This is by no means comprehensive and is ultimately a guide from my own personal experiences for people to wrestle with on their own. The FAO guidelines are much more vague, leaning on respectability politics and vague notions of ecological justice. What’s fundamental to our understanding of agroecology, essentially, is that it is driven by a complex web that isn’t just about productivity or abundance, but rather addresses systemic inequities, not just for humans. Ecology is a complex web that shows a good life simply cannot be made for all people, without making a good life for all life.

In this way, agroecology is just as slippery as other alternatives to industrial agriculture. However, the underpinnings are based on equity for all, not just those with access. It is for this reason that agroecology offers a path forward in the face of ecological destruction, colonialism, and a rotting economic system. It has to, and we have to make it.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, which is equal to a 33 page chapter, of (so far) a 6266 page book with 294 sources, you can support our work in a number of ways. The first is by sharing this article with folks you think would find it interesting. The second is by listening and sharing the audio version of this content (which will come out in October 2023), the Poor Proles Almanac podcast, available wherever you get your podcasts. If you’d like to financially support the project, and get exclusive access to our limited paywalled content, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack or Patreon, which will both give you access to the paywalled content, and in the case of Patreon, early access to the audio episodes as well.

Richards, P. 1985. Indigenous Agricultural Revolution. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Altieri, M.A., and V.M. Toledo. 2011. “Te agroecological revolution in Latin America: Rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants.” Journal of Peasant Studies, 38: 587–612.

Rosset, P., and M.E. Martínez-Torres. 2012. “Rural social movements and agroecology: Context, theory and process.” Ecology and Society, 17, 3: 17.

The historical conditions of Latin America during this period are complex, and the geopolitical movements of the “de-peasantizers” and the “peasantists” who spoke about the future of the peasant class.

van der Ploeg, J.D. 2009. To New Peasantries: New Struggles for Autonomy and Sustainability in an Era of Empire and Globalization. London: Earthscan.

Rosset, Peter, and Miguel A. Altieri. Agroecology: Science and Politics. Practical Action Publishing, 2017.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the U.N.). 2014. “International Symposium on Agroecology for Food Security and Nutrition.” .

IPC (International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty). 2015. “Report of the International Forum for Agroecology, Nyéléni, Mali, 24-27 February 2015.” .

ETC Group. 2009. “Who will feed us? Questions for the food and climate crisis.” etc Group Comunique #102.

For an example of this individuality over community, tune in here to the Poor Proles Almanac interview with Maya farmers in Belize: “Modern Maya Milpa with Dr. Anabel Ford & Maya Farmers”

Christian Aid. 2011. “Healthy harvests: The benefits of sustainable agriculture in Asia and Africa.”

Bachmann, L., E. Cruzada and S. Wright. 2009. Food Security and Farmer Empowerment: A Study of the Impacts of Farmer-Led Sustainable Agriculture in the Philippines. Masipag-Misereor, Los Banos, Philippines.

Dyer, G. 1991. “Farm size-farm productivity re-examined: Evidence from rural Egypt.” Journal of Peasant Studies, 19, 1: 59–92.

Dorward, A. 1999. “Farm size and productivity in Malawian smallholder agriculture.” Journal of Development Studies, 35: 141–161.

Sternsher, Bernard (1964). Rexford Tugwell and the New Deal. Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

To learn more about the Womens’ Natural Farming Collectives, listen here to the Poor Proles Almanac interview titled “The Women Collectives behind India’s Farming Revolution”

Sanchez, J.B. 1994. “La Experiencia en la Cuenca del Río Mashcón.” Agroecologia y Desarrollo 7: 12–15.

SANE. 1998. Farmers, ngos and Lighthouses: Learning fom Tree Years of Training, Networking and Field Activities. Berkeley: sane-undp.

“How Much Time Does a Farmer Spend to Produce My food? An International Comparison of the Impact of Diets and Mechanization” by María José Ibarrola-Rivas, Thomas Kastner and Sanderine Nonhebel

We outlined some of these potential shortages here in the Poor Proles Almanac episode “Climate Change & Modeling Complex Systems Theory”

Alonge, Adewale J., and Robert A. Martin. 1995. “Assessment of the adoption of sustainable agriculture practices: Implications for agricultural education.” Journal of Agricultural Education, 36, 3: 34–42.

The Poor Proles Almanac interview Vijay Kumar Thallam, advisor to the Indian government as a representative of the farming movement here, where we discuss these dynamics and how the historical context helped drive the movement’s exponential growth.

Brown, C., and S. Miller. 2008. “Te impacts of local markets: A review of research on farmers markets and community supported agriculture (csa).” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 90, 5: 1298–1302.

CSM (Civil Society Mechanism). 2016. “Connecting smallholders to markets.” International Civil Society Mechanism for Food Security and Nutrition, Rome. .

https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/8898/1/DiscussionPaper_235.pdf

https://www.americanprogressaction.org/article/working-class-americans-states-support-progressive-economic-policies/

https://www.science.org/content/article/native-tribes-have-lost-99-their-land-united-states

Thank you for this, fascinating and something I am now inspired to learn more about.

ah man, what a resource!